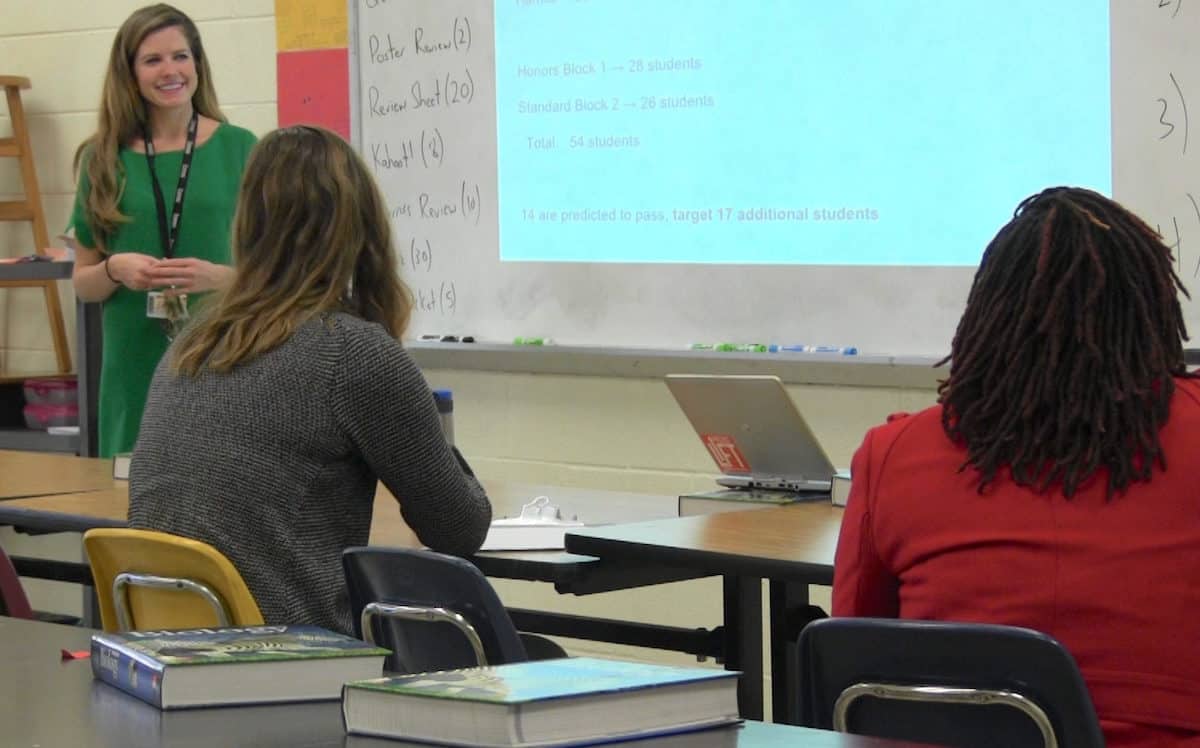

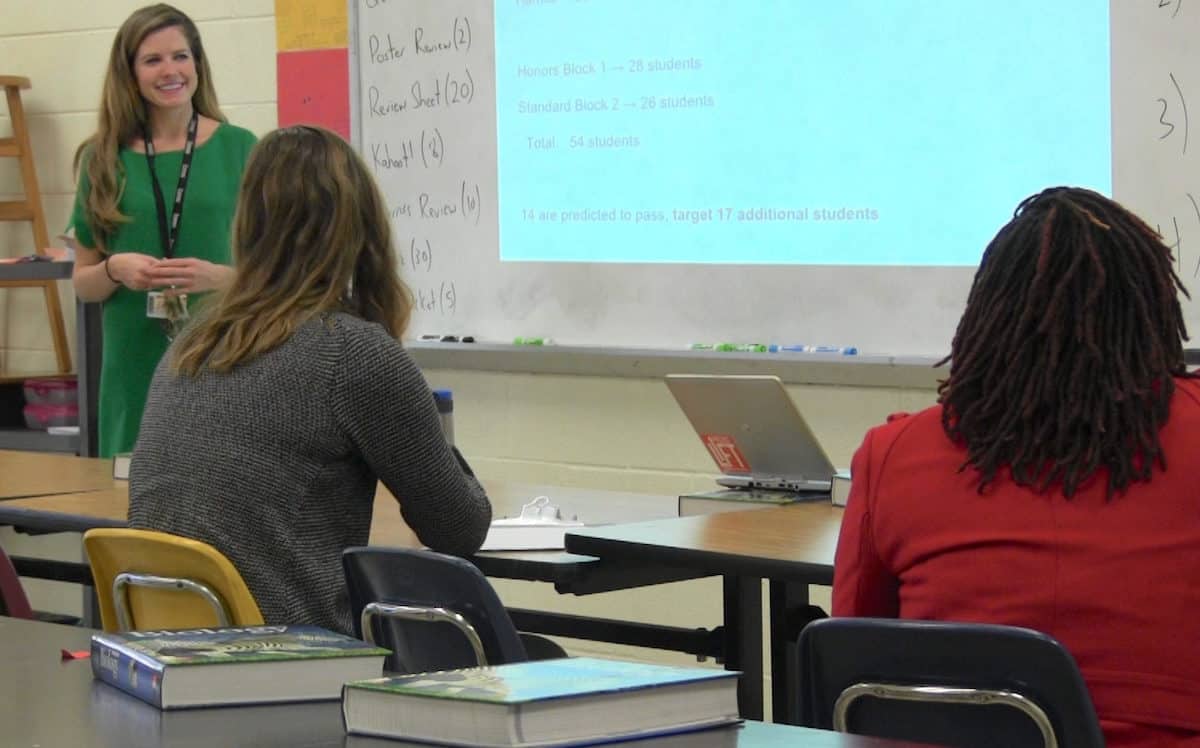

Keep doing what works: For Erin Burns Mehigan, that message has been central to her school’s shift to at-home teaching and learning. Now an assistant principal at Jay M. Robinson Middle School in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, Mehigan was a multi-classroom leader at West Charlotte High School and a 2015–16 Opportunity Culture Fellow.

She took what worked for her as a multi-classroom leader to her assistant principalship, which includes leading the team of science teachers, as well as all seventh-grade teachers. She leads regular team meetings, which now gather on Zoom twice a week to continue their work to use data-driven instruction, discuss how to hold small-group instruction virtually, and develop at-home schedules that support students without overwhelming them.

In a recent conversation, Mehigan highlighted the teachers’ dedication and eagerness to keep going when school buildings closed. District guidance said not to introduce new material for the first few weeks, but they miss their students, she said, and are “chomping at the bit to start new content.”

The school asks teachers to post instruction each day that includes a video or audio component — recorded or live — so students have some sort of face-to-face interaction. On alternate days when teachers don’t have team meetings, they are asked to provide live instruction for a minimum of an hour, often split up into small-group sessions. They also have time in the afternoons and all day Friday to pull small groups or individual students for specific instruction by videoconference.

“We’re kind of envisioning it like a flipped classroom model,” Mehigan said, meaning students come to live instruction with homework or a digital lesson completed, so they can use the videoconferencing to ask questions or engage in discussion.

Mehigan’s teachers list her in the apps they use, such as Google Classroom, as a co-teacher, so she can support their work and be able to step in if a teacher gets sick. The school has set strict requirements that each team be consistent in what is taught, enabling a smoother transfer to another teacher if needed.

She and the school’s other leaders have been planning the rest of the year on the assumption that distance learning will be required for quite a while, so they want tools that make a digital version of in-class instruction possible, while acknowledging that some things may change, including grading policies, attendance, and what constitutes mastery.

Among her tips and issues to consider:

What counts as attendance. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools have a one-to-one Chromebook policy, but when we spoke, some families still had not been able to pick one up, making it difficult to dock points for “attendance,” however it ends up being defined.

What works for assignment due dates. “The idea of these daily deadlines for turning in work is probably not going to work,” Mehigan said; weekly deadlines seem more realistic and give students some control of and accountability for their study schedules.

What constitutes mastery. How do teachers gauge mastery of a topic when essentially all work, including tests, must be assumed to be “open-book”? Mehigan’s team has been working on creating test questions about core concepts so students cannot just regurgitate notes. And seventh-grade teachers will let eighth-grade teachers know what standards receive less coverage during the at-home phase, so they can begin next year by reteaching them as needed—not an ideal situation, but realistic, she said.

For many teachers, accepting these changes can feel challenging, since it breaks some traditional expectations and rules for student behavior. “A lot of our teachers take their role so seriously — which I appreciate,” she said, but which forces a mindset shift.

Suspending end-of-grade testing for this school year will relieve significant stress for them, she said. “So many of our teachers are understandably very motivated by their students’ results — they’re competitive people, and I appreciate that. But I think that having this lack of control of the situation was really taking a toll on some people — that ‘how am I supposed to exceed growth again or have 95% of my kids pass this EOG if I can’t even guarantee that I’m going to see them?’”

Throughout this planning, “it’s on our mind how we’re going to be equitable and understanding, but also holding kids to high standards and making sure that they’re mastering what they need to master for their grade level,” Mehigan said.

What guidance teachers need about how to communicate a consistent message. “There’s just so much room for interpretation that we are having to be more explicit than normal, almost like, ‘here is a sample email, copy and paste and insert your name here,’” Mehigan said. “This is so new for everybody, and everyone’s interpretation of what is going on is a little bit different, that it’s just been a big challenge trying to have one message out of the school. … Make sure it’s all uniform.”

For more, see Erin Burns Mehigan’s columns, More Powerful Than a Department Chair, and How to Extend the Reach of Great Teachers in Turnaround (or Any) Schools.

See short video clips of Mehigan that are part of our Instructional Leadership and Excellence resources, including Leading When New to a School and Frequent Small Assessments Are Key.

Editor’s note: This perspective was first published by Opportunity Culture. It has been posted with the author’s permission.