|

|

As schooling resumes amid yet another virus surge and as an election cycle intensifies, two events with anniversaries on the same date, Jan. 6, put into perspective basic decisions facing our state and nation in 2022.

A year ago on Jan. 6, supporters of former President Donald Trump stormed the United States Capitol, with more than 700 of them subsequently charged with crimes. They failed in their objective of blocking the certification of Joe Biden as the duly elected president, but the style of politics that had given rise to such an insurrection continues to ripple across the state and nation.

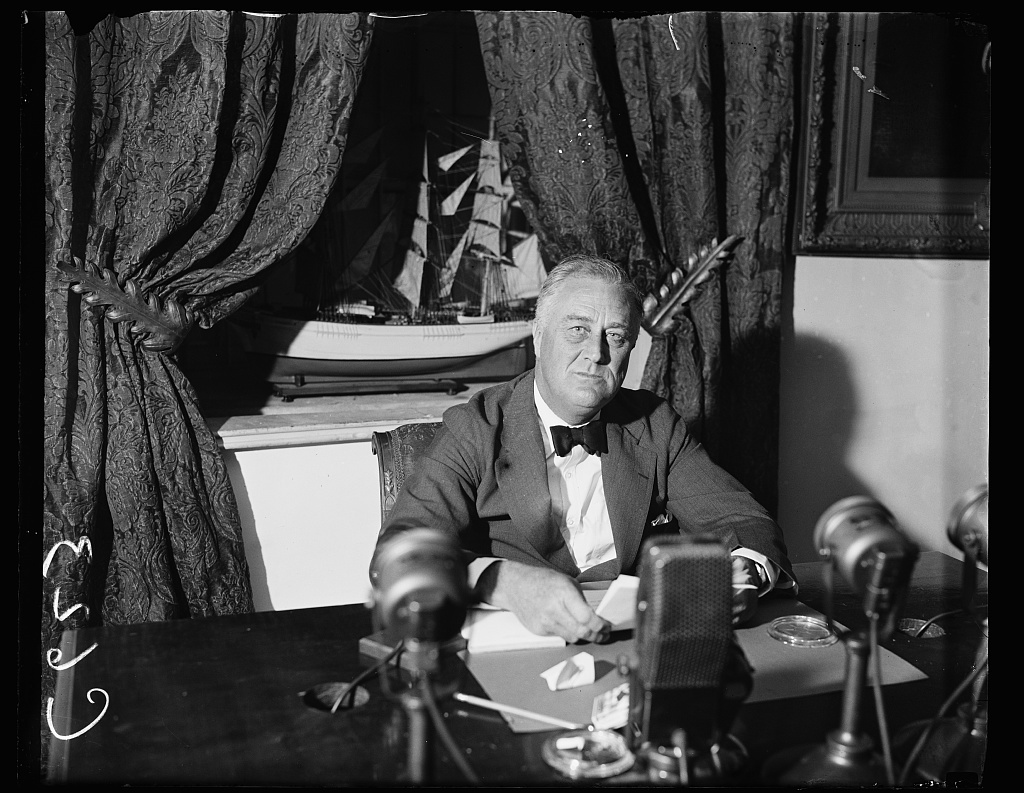

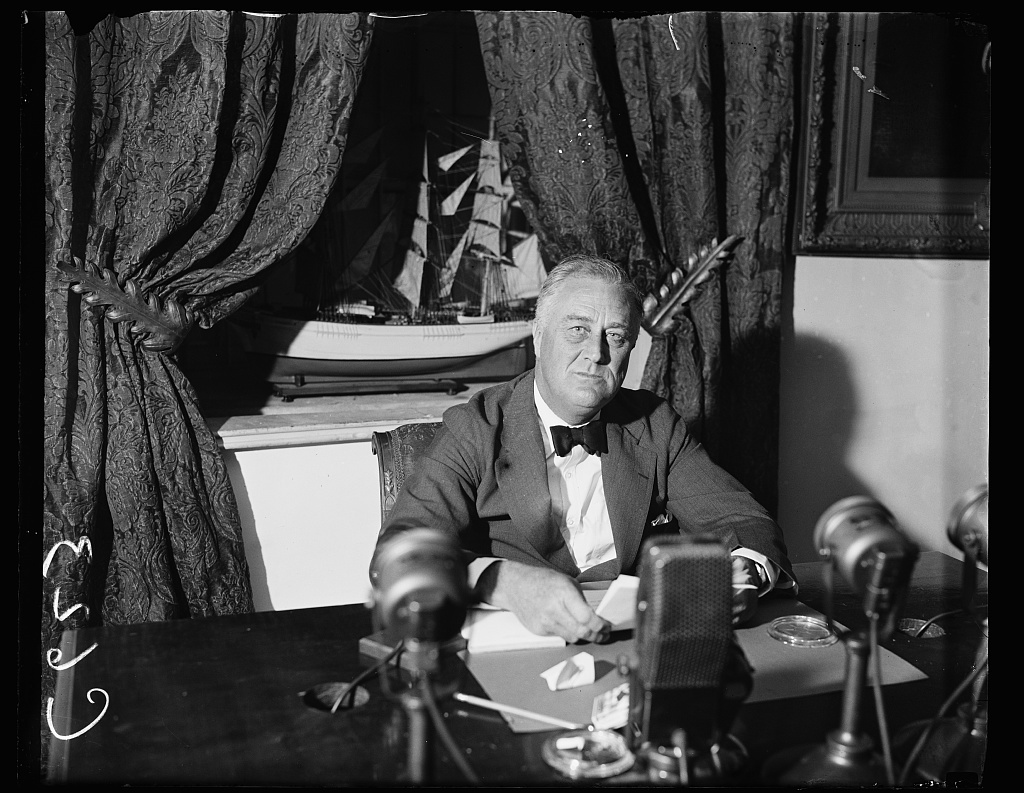

Eighty years earlier, Jan. 6, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt went to the Capitol to deliver a State of the Union address to a Congress and a citizenry anxious and divided over the prospect of war abroad against an alliance of dictatorships. He enunciated “four essential human freedoms,” well worth the attention of teachers, students, and citizens for insight into addressing today’s crisis in democracy.

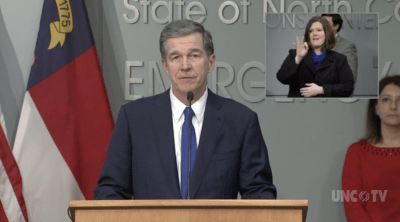

North Carolina appears destined to have a central role in the multi-layered political competition of 2022. It is among the states with a race for an open seat in the U.S. Senate, in which Trump has already endorsed one of the candidates for the Republican nomination. In state court this week, arguments were heard over the extensive gerrymandering of congressional and legislative districts to enhance the prospects of Republican control in Congress and in the General Assembly.

And in North Carolina as well as across the country, education-related topics have emerged as “wedge issues” for conservative forces intent on culture-war politics. The victory of Republican Glenn Youngkin in the 2021 Virginia governor’s race serves as a model in mobilizing voters opposed to mask-wearing requirements and to efforts to deepen the exploration of the country’s racial history in schools. On such issues, North Carolina Republican Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson and U.S. Rep. Madison Cawthorn had already turned up the heat on state and local school authorities.

The American Enterprise Institute, a major Washington-based think tank, has published a paper calling for making school board elections more partisan by identifying candidates by party and scheduling them on the cycle of national elections. “Our facially nonpartisan system of education governance,” the paper contends, “also conceals the political reality that much of public education’s expert class holds firm ideological commitments substantially out of step with the broader public.”

Of course, now is not the first “crisis” moment in the history of American democracy — though the insurrection at the Capitol and the rejection of the outcome of a free and fair election even among elected officeholders amount to an especially serious moment.

In his time, Roosevelt initially confronted the crisis of the Great Depression and then aggression by the Axis powers, both presenting dangers to democracy. When he spoke in the U.S. House chamber on Jan. 6, 1941, Roosevelt had just won an unprecedented third term in the White House.

The nation had still not fully recovered from economic depression and had a strong streak of isolationism. The president’s immediate objective was to win support for his Lend-Lease plan to provide Great Britain with weaponry.

Roosevelt went further. He enunciated four freedoms:

“freedom of speech and expression.”

“freedom of every person to worship God in his own way.”

“freedom from want.”

“freedom from fear.”

“Since the beginning of our American history,” FDR said, “we have been engaged in change — in a perpetual peaceful revolution — a revolution which goes on steadily, quietly adjusting itself to changing conditions — without the concentration camp or the quick-lime in the ditch.” And, he said, “the justice of morality must and will win in the end.”

In the fraught, fractious year just beginning, Roosevelt’s “four freedoms” offer Americans a broader vision and a set of ideals with which to apply to the crisis of the present and to reinforce the future of American democracy.