On a recent Sunday morning, I woke up to see tremendous chatter on social media concerning the budget impasse in the North Carolina General Assembly. The discussion included the lack of educator raises, the failure to expand Medicaid, unacceptable working conditions, and a shortage of support staff. This discussion quickly evolved into the formation of a new social media group discussing the possibility of a large scale collective action or strike of North Carolina educators.

This kind of discussion is not new to me. I’ve been a sixth grade social studies and language arts teacher for 18 years, working my whole career in a diverse community confronted with significant economic struggle. I love my community, and they have always inspired me to advocate for my students and their families. Recently, I decided to take an Inquiry to Action class through the Western Region Education Service Alliance (WRESA) to earn continuing licensure credits and build my activist skills. Here, a small group of educators studied educator activism in both theory and practice. Each week we discussed a different education-related activist tool, theory, and issue. The culminating project was to take our “inquiry” and put it into “action” in some way.

The group decided to focus on “making the invisible visible.” In other words, we seek to deepen critical consciousness — the notion that we go through life oblivious to the world around us on the largest scale. A famous example of this precept is the analogy of the fish in water. If you asked a fish what water is, the fish wouldn’t understand the question because it has a fish brain.

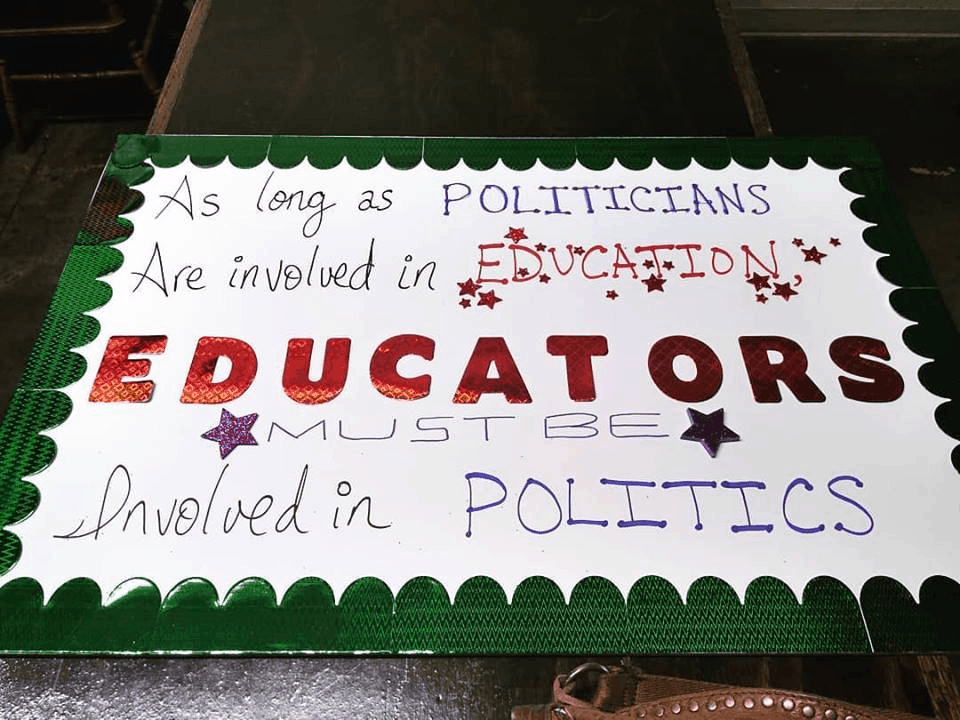

Joking aside, it is because the fish is completely immersed in the water and always has been. The fish just doesn’t notice because it is so “normal” and so ubiquitous. In human life, this would be like the systematic racism that we all live within. Or, it may be ideas that are simply taken as “common sense.” For educators, we may struggle to apprehend fundamental truths about our own environments. I believe that public educators swim in a sea of politics which is all too often invisible — so that is the concept I choose to render more visible.

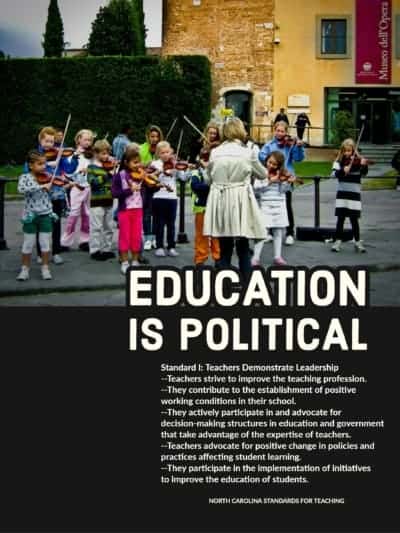

Most North Carolina local school boards have policies which hold that employees may not engage in political activities during the school day. However, because public schools are supported by public monies which are controlled by politicians, the very act of teaching, while not partisan, is an inherently political activity. In fact, North Carolina’s evaluation instrument for educators insists upon educators taking part in political activities. Standard 1 (Teachers Demonstrate Leadership) states, “Teachers advocate for schools and students. Teachers advocate for positive change in policies and practices affecting student learning.” What is advocating for policies if not political?

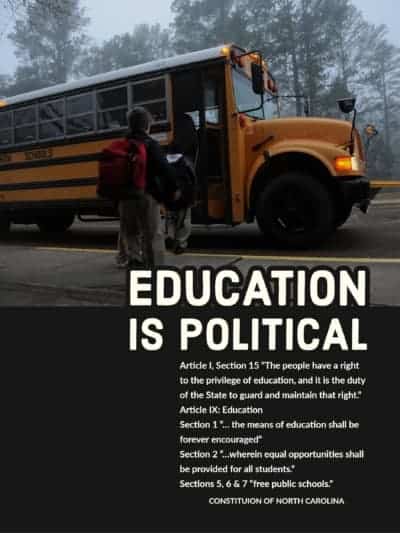

To test just how visible this idea of “education as political” might be, I created a few info graphics and shared them with my virtual colleagues on social media. I also shared a quick survey to gauge their response.

As a politically active educator myself, I’m an engaged member of dozens of groups including the North Carolina Association of Educators, Red4EdNC, and North Carolina Teachers United. Accordingly, I shared my ideas with thousands of educators across the state, most of whom are interested or involved in education advocacy and activism. What I found in my survey is that more than 90% of respondents agree that education is political. The caveat is that this survey was given to people who are already active enough to be in educational groups online. What about everyone else? And are they all willing to act?

That question is why I decided to write this piece. What do principals and superintendents think about this question? What about educators who “just shut the door and teach?” What about educators in more affluent communities who have been privileged by virtue of race and/or class to “stay out of politics?” Does the notion that education is political translate to educators who aren’t already politically engaged?

Our state constitution specifically gives the people the right to education and insists that “the means of education shall be forever encouraged.” Furthermore, the Leandro court case determined that we have not fully met our constitutional requirements for “the resources necessary to support the effective instructional program … so that the educational needs of children may be met.” Our constitution, the Leandro case, and our evaluation instrument seem to be imploring us to become more politically active.

As overworked as educators already are, all indicators compel me to be as politically engaged as possible. North Carolina citizens and students won’t get beyond the current climate of attacking and dismantling public schools with our democracy intact unless all teachers are rated “distinguished” on Standard 1 in the teacher evaluation instrument.

We must vote out the privitizers and those who would see public education wither through lack of funding. We must advocate for the most vulnerable and for ourselves. We must hold every politician accountable for performing their constitutional duties as it relates to public education.

We do this by making the invisible visible and holding it up for all to see.