|

|

On Oct. 4, 1957, the USSR launched Sputnik I, the first artificial earth satellite to successfully enter orbit. In the United States, the reaction was swift—how could our educational system have let us down? Since that time, educational reformers have leveraged “sputnik-like” moments to propose and enact changes to the way we run our public schools. At stake in these reform initiatives is how to strike a balance between holding schools accountable for student performance, while also providing schools with enough local autonomy to make decisions that seem best to them.

For example, when the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) became law in 2015, it codified a notable shift from rigid, high-stakes accountability to flexibility and local autonomy. Specifically, ESSA did away with uniform measures of school performance required under No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and let individual states determine how they would identify and intervene in their lowest-performing schools. Importantly, while flexibility can catalyze innovation, looser accountability requirements also make it easier for students to “slip through the cracks.” Therefore, an important question remains: What is the right balance between accountability and autonomy?

To help answer this question, we independently evaluated the impact and implementation of North Carolina’s Restart (NCR) program. In early 2016, North Carolina updated its NCR policy to move away from school takeover by an external operator and instead allow continually low-performing schools to apply for “charter-like” flexibility from statutes that bind other traditional public schools, such as flexibility in funding, learning time, curriculum, and compensation, to name a few. In this way, NCR inverts traditional reform approaches (i.e., an all-carrots-no-sticks strategy), offering important lessons for current educational policy discussions.

To examine NCR, we used statewide administrative data from 2011-12 through 2018-19. We applied rigorous statistical methods to examine student test scores, attendance, chronic absenteeism, discipline, drop out, and graduation. We also compiled improvement plans for all NCR schools to compare whether some proposed flexibilities were more strongly associated with positive outcomes than others. Additionally, we interviewed school and district leaders to gather their perspectives on NCR implementation. Below, we share key findings from NCR outcomes before the COVID-19 pandemic began. In future work, we will use post-pandemic data to examine how NCR schools are faring post-pandemic.

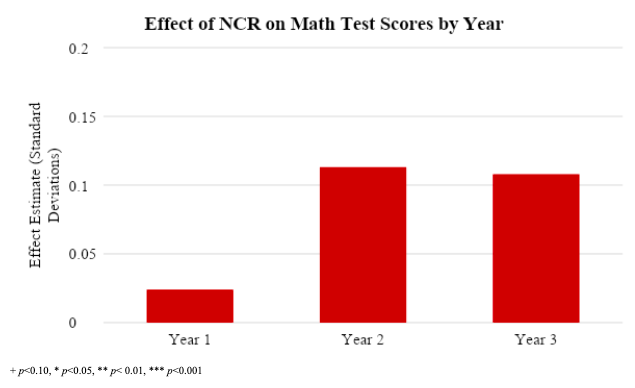

Finding 1: NCR improved math test scores but not any other student outcome.

The graph below shows the effect of NCR on student test scores in math in the first three years after schools gain flexibilities. The estimates suggest potential positive effects after one year of implementing NCR. This effect grows in year 2; the 0.11 standard deviation effect translates to nearly two months of additional learning in NCR schools, relative to similarly low-performing but non-NCR schools. The effect in year 3 is positive but not statistically detectable. The positive effect in math is encouraging evidence that some increased flexibility can help schools improve.

However, the results do not offer unconditional support for NCR. We do not observe a relationship between NCR and student test scores in English Language Arts (ELA), attendance, chronic absenteeism, disciplinary outcomes, drop out, or graduation. The lack of a relationship with these other outcomes suggest that NCR could focus more attention on other meaningful student outcomes beyond short-term improvements on test scores.

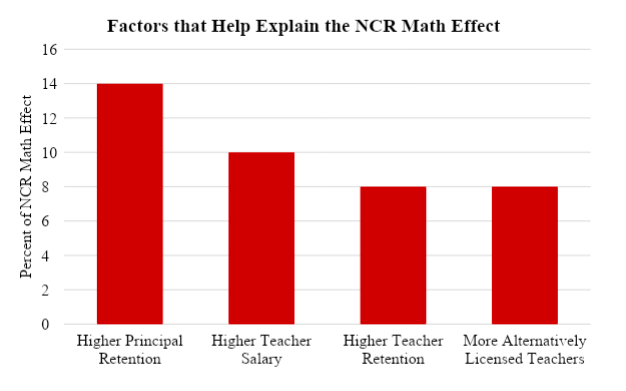

Finding 2: Most NCR schools proposed increasing teacher pay, but principal retention explained the largest share of positive NCR effects.

Over 70% of NCR schools proposed flexibility by altering how, and how much, teachers are paid — the most commonly proposed intervention. Principals also described using NCR flexibilities to hire unlicensed teachers who they believed would be a good fit, provide additional professional development for teachers, extend learning time, and change the curriculum. Of these interventions, only increased teacher pay was associated with more positive NCR effects. In fact, we found that schools proposing many disparate interventions produced lower student test scores, underscoring the need for focused and coherent improvement plans.

Below we display the four factors that played the biggest role in producing positive NCR effects. The most important factor available in our data was increased principal retention, which explains 14% of the overall NCR math effect. Increased teacher pay was also important, explaining 10% of the NCR math effect. Given the large proportion of NCR schools that proposed increasing teacher pay, the fact that increased pay explains some of the positive NCR math effects is evidence that school leaders were making effective compensation decisions.

We also highlight the finding that NCR schools hired more alternatively licensed teachers than non-NCR schools, and alternatively licensed teachers explains 8% of the NCR effect. This finding does not make any comparisons between the effectiveness of traditionally- versus alternatively-certified teachers. Instead, it suggests that NCR principals are making sound decisions when they do choose to hire unlicensed teachers because the teachers they choose are contributing to improved test scores.

Finding 3: Principals report many ambiguities that require extensive effort and time to coordinate with district administrators.

NCR schools have “charter-like” flexibility, but the definition of “charter-like” is unclear. NCR principals reported spending considerable time and energy discussing and resolving disagreements with district administrators over what the NCR flexibilities allow them to do. One principal shared:

Everyone understands we have flexibilities, but they want to control those flexibilities and tell you which ones you can use. So, you might have five conversations with HR [human resources] to use licensure flexibility on a plan the board’s voted on, a plan the superintendent supports, and yet you end up having to prove over and over and over that, ‘Yes, I can hire this person.’

The heavy burden on principals means that some did not have capacity to pursue innovative reforms under NCR. To lessen the load, principals recommended a districtwide NCR coordinator who could explain and advocate for principals’ requests.

Overall, our examination of NCR provides modest evidence that increased flexibility and school-level autonomy can be a useful tool for improving low-performing schools. However, as currently implemented, NCR places a heavy burden on school principals, whose retention is an important part of positive NCR effects. We recommend stronger support for principals implementing NCR and urge state leaders to clarify and communicate guidelines for how NCR schools can use their increased flexibility.