Too often, the quote within the title is spoken by Black families searching for an answer for their children who are undiagnosed with autism. Although one in every 44 children in the United States was diagnosed with autism in 2018, the timeliness of diagnosis differs greatly by race. Black children with autism experience a delay in diagnosis and/or misdiagnosis more than White children 1 2 3 4. Black parents schedule visits, attend appointments, and speak with health professionals about their concerns. However, Black families are frequently dismissed. Thus, the delay commences.

The delay and its impact

Autism diagnoses in Black children are delayed by almost three years. This delay takes into account the initial visit when Black parents report autism-related concerns to their provider and the time it takes to receive the autism diagnosis.

“… It’s not the parents who are delaying diagnosis, it’s the system[s],” said Daniel Geschwind, director of the Center for Autism Research and Treatment at the University of California, Los Angeles, to HealthDay reporter Steven Reinberg. Medical and educational systems contribute to delayed diagnoses and to misdiagnoses for Black children with autism. Delayed diagnoses lead to postponed treatment and service usage 5, worsened symptoms, increased indirect financial burdens for families, and higher rates of intellectual disability. “We’re talking about very serious numbers of people affected by [these delays],” said Dr. Constantino to Spectrum News.

Kristian’s story

One family impacted by provider dismissal and delayed diagnosis is that of Krystal Lee, a Black single mother of five children. She experienced an almost three-year delay before an autism diagnosis was received for her son, Kristian. “When Kristian was about four months old, I noticed he was responding differently than his twin. When I expressed my concerns to doctors, they disregarded everything I said. ‘There’s nothing wrong with him. People have different times of when they learn different things… You can’t expect one child to be just like the other children.’ And I kept saying, ‘I understand what you are saying… but at the same time I know when something is not right with my child. I know.’”

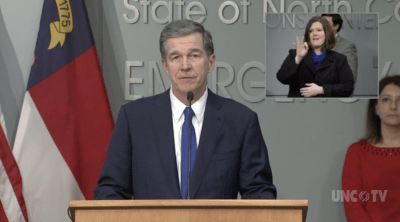

Kristian and his twin.

Krystal and Kristian.

Kristian’s autism diagnosis and access to services did not come until Krystal received help from professionals at Kristian’s daycare center when he was about 3 years old. “What really jumpstarted the services was a speech therapist who was at the daycare for another child. She made the recommendation,” Krystal said. “It took a White woman to get the ball rolling for my son. It took her voice instead of mine, when I am his mother. But…I am just grateful that we are at the place we are now.”

Currently, Kristian is 10 years old and has been receiving treatment, special education services, and related services for his autism since preschool. With his accommodations, services, and support, Kristian is performing well in school and is flourishing.

The reality of it all

Every Black autistic child does not have Kristian’s story, but many Black parents share Krystal’s frustrations. Some Black children experience delays in autism diagnosis well into grade-school-age, putting treatment further behind and adding stress to their families. “[We have to] at least try to see whether some of this can be resolved by leveling the playing the field for diagnosis and access to services,” said Dr. Constantino. Changes to the systems are warranted. But how?

One viable solution

Training general education (GE) teachers to recognize and identify symptoms of autism is a practical feasible solution to aiding the closure of the diagnosis gap and consequent treatment gaps.

The public school system may be the ideal place to start, as Black families and minorities are more likely to report autism-related symptoms to school staff. Minority families also feel schools are better at responding to their autism-related needs than healthcare professionals are; more specifically, diagnosis seeking behaviors and initial referrals 6. Moreover, GE teachers are around students about eight hours a day and witness them across several settings and social situations. Training these teachers to help with identification of autism may improve Black autistic children’s diagnosis timelines and overall outcomes.

The training module

I propose a community-based, 10-day modality training that incorporates interactive hands-on strategies. The first two days would extensively cover autism knowledge, disparities, symptom awareness, identification, documentation, and assessment. Then, another two days of activities would address biases and positionality to help teachers become more aware of their personal stances that may interfere with their judgment. Combined, these approaches would lay the theoretical foundation of autism and emphasize the need for unbiased assistance from well-trained GE teachers.

The next two days of training would be directed towards teaching children with autism, implementing behavioral supports, providing their accommodations, and working with related services in the GE setting. Then, two days of trainings would focus on tying everything together while employing cultural responsiveness and culturally sustaining pedagogies 7 or teaching practices to prepare GE teachers to understand and embrace cultural differences, which may further aid the identification and referral processes.

Finally, to put theory into practice, the community-based training facilitators would provide two days of assistance to GE teachers in their classrooms, where teachers could use their training to benefit their students and to promote inclusion. The facilitators can observe, provide immediate feedback, and guide teachers in real time. This would benefit the teacher and solidify learned material. But, most importantly, it would help children and aid with accurate, timely autism diagnoses.

Confident teachers

When GE teachers are properly trained and equipped to recognize symptoms of autism, they can better advocate for their students. Black autistic students require this advocacy to assist with closing the diagnosis time gap they experience. If implemented with efficacy, trained teachers can feel confident in their referral to the school and family for the evaluation of a Black child who presents with autism-like features.

Attainment of an accurate diagnosis may improve the child’s access to services and treatment, which are related to improvements in overall functioning for autistic children8. A parent “knows when something is not right.” Teachers can too. Let’s train them. Black autistic children deserve all of the good that can come from it.