The John M. Belk Endowment and Durham-based nonprofit MDC have partnered to examine the patterns of economic mobility and educational progress in North Carolina to determine who is being successfully prepared for entry and success in the most economically rewarding sectors of the state’s economy. The report, “North Carolina’s Economic Imperative: Building an Infrastructure of Opportunity,” provides data and analysis on these trends and includes a close look at eight localities across the state. This week, EducationNC will be featuring the profiles of five of those communities.

In the late 1800s, brothers Moses and Cesar Cone built Revolution Mills in Greensboro, N.C., the first flannel mill in the South and a central part of their Guilford County enterprise, the Southern Finishing and Warehouse Company. At the height of production, Revolution Mills contained more than 1,000 looms, and by the 1930s was the largest exclusive flannel producer in the world. However, the decline in manufacturing that hit the South in the 1980s also challenged Revolution Mills—the factory closed in 1982. Now, more than 100 years after its opening, the mill houses a different sort of revolution: the Nussbaum Center for Entrepreneurship. There are plans for continued invigorating renovations including apartments and artist studios. The story of Revolution Mills is the story of Guilford County: once the home of textiles, now the home of the new knowledge economy; once it brought traditional manufacturing to the area, now it is bringing entrepreneurship and innovative technologies. High Point and Greensboro, Guilford County’s largest municipalities, are each leading efforts to create a workforce that matches the strength of their past and is prepared for the future.

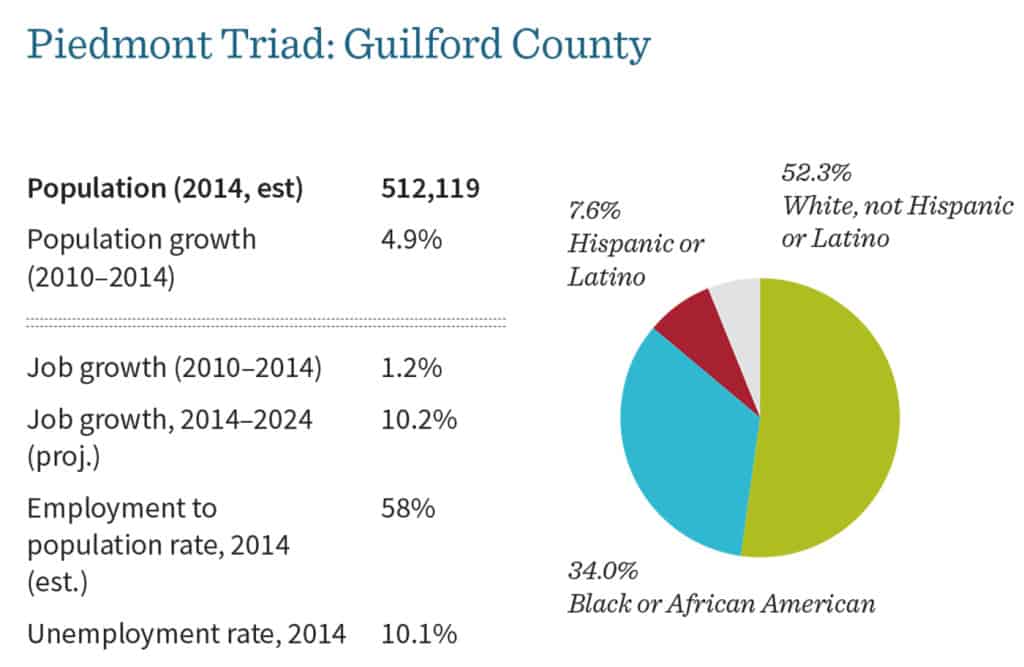

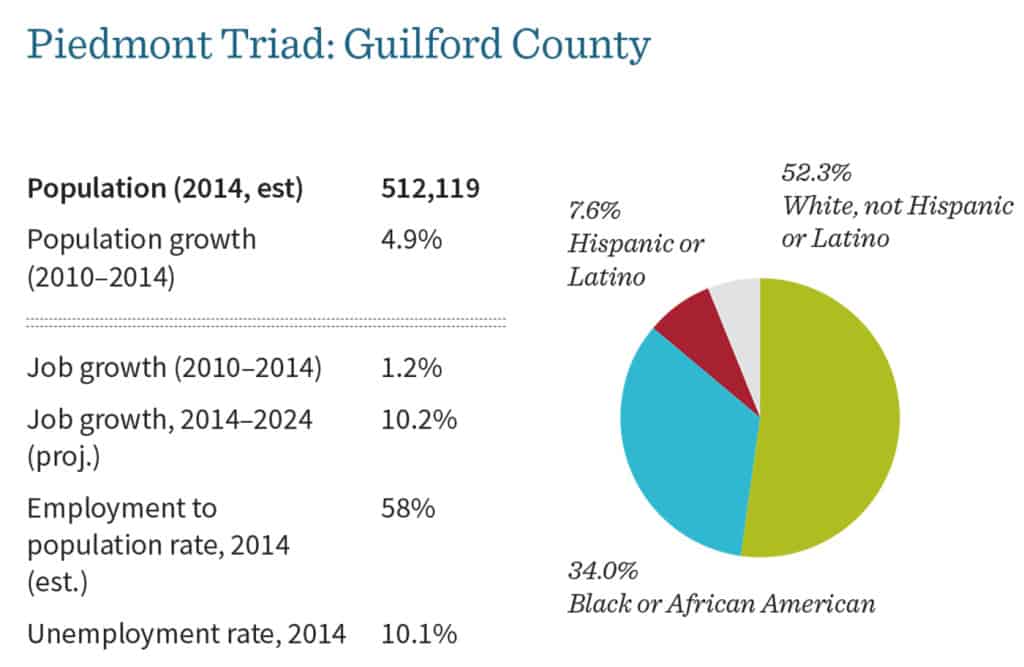

Guilford County, part of the Piedmont-Triad region of North Carolina, is the third largest county by population in North Carolina. If you’re driving on I-85 between the state’s two most populous counties, Wake and Mecklenburg, Guilford is right in the middle. And if you exit off the interstate in Guilford, you’ll immediately notice all the signs for the many colleges and universities there. The oldest college in the county, Guilford College, was founded by the Quakers in 1837 and was followed one year later by Greensboro College. Guilford is also home to two historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs), a UNC-system institution, a community college, and other private institutions, including High Point University. More than 40,000 undergraduate students attend college in Guilford County. And knowledge is key to Guilford’s economic growth. A 2004 study showed that UNC-Greensboro was worth $1.22 billion to the region’s economy. According to the Greensboro News & Record, “that puts it squarely in league with the Moses Cone Health System, Piedmont Triad International Airport and the International Home Furnishings Market in High Point as a driver of the region’s economy.”1

The Cone Brothers were not the only entrepreneurs who found Guilford fruitful for manufacturing. High Point became a boomtown for furniture manufacturing (the “furniture capital of the world”) and Greensboro thrived in textiles. Fabric-maker Burlington Industries came to the area in the 1930s and Guilford Mills was founded in 1946. By the 1940s, more than 60 percent of North Carolina’s textile and hosiery facilities were located in the Piedmont-Triad region. Other industries also played roles in Guilford’s economic history, including insurance services (Jefferson-Pilot) in the early 1900s and aviation (TIMCO and HondaJet) in the 1990s and 2000s.

Manufacturing lives on in Guilford County through its philanthropic legacy. Several business leaders created foundations with their earnings, including Cesar Cone with the Cemala Foundation, Edward Armfield, Sr. with the Armfield Foundation, and James Millis with the James H. and Jesse E. Millis Family Foundation. After the decline in manufacturing, these foundations and others invested in their community to keep Guilford County going. Many fund initiatives in Guilford today.

Besides being known for manufacturing, Guilford is also known for its memorable civil rights history. There was a series of nonviolent sit-ins in 1960, starting with the notable “Greensboro Four” sit-in, where four North Carolina A&T State University freshmen sat at Woolworth’s all-white lunch counter and refused to leave. That sit-in led to numerous other sit-ins across the state and the South, including in High Point, where 26 high school students also staged a sit-in at their local Woolworth. While Guilford continues to be challenged by racial disparities in education, employment, criminal justice, and other factors, community members celebrate their social justice history with events like the two-week Fabric of Freedom festival and community-wide conversations on race and equality. When discussing partnerships, Guilford residents are quick to point to their Quaker history and Jewish heritage. The narrative is one of inclusion and progressive attitudes, undergirding messages of community empowerment and social justice that resonate today through many of Guilford’s collaborative efforts. Indeed, Steve Moore, the executive director of Degrees Matter, calls Guilford the “moral compass” of North Carolina.

In a recent interview, Dr. Harold Martin, president of NC A&T, discussed growing up as a black student in nearby Winston-Salem during the 1950s and 1960s. “I grew up in that window of time when neighborhoods, jobs, and institutions were segregated. All of my experiences growing up were in that segregated experience. Throughout K–12, all of the educational experiences I had were with black teachers who looked at bright students and believed strongly that education was the great equalizer. There was no exception. ‘You are going to college; it was not an option.’ These teachers coupled with parent expectations pushed you towards what they believed were the avenues that would lead to a better life for you.”2

“Throughout K–12, all of the educational experiences I had were with black teachers who looked at bright students and believed strongly that education was the great equalizer. There was no exception.” — Dr. Harold Martin, president, NC A&T

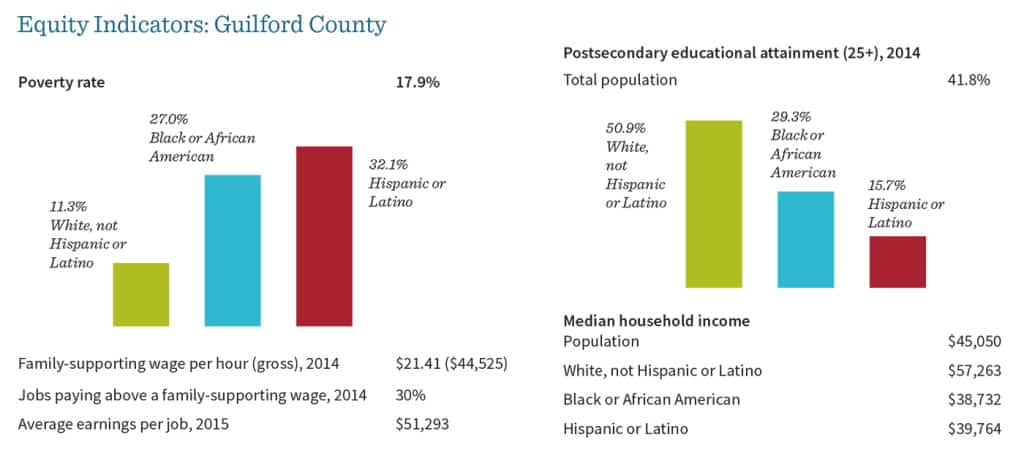

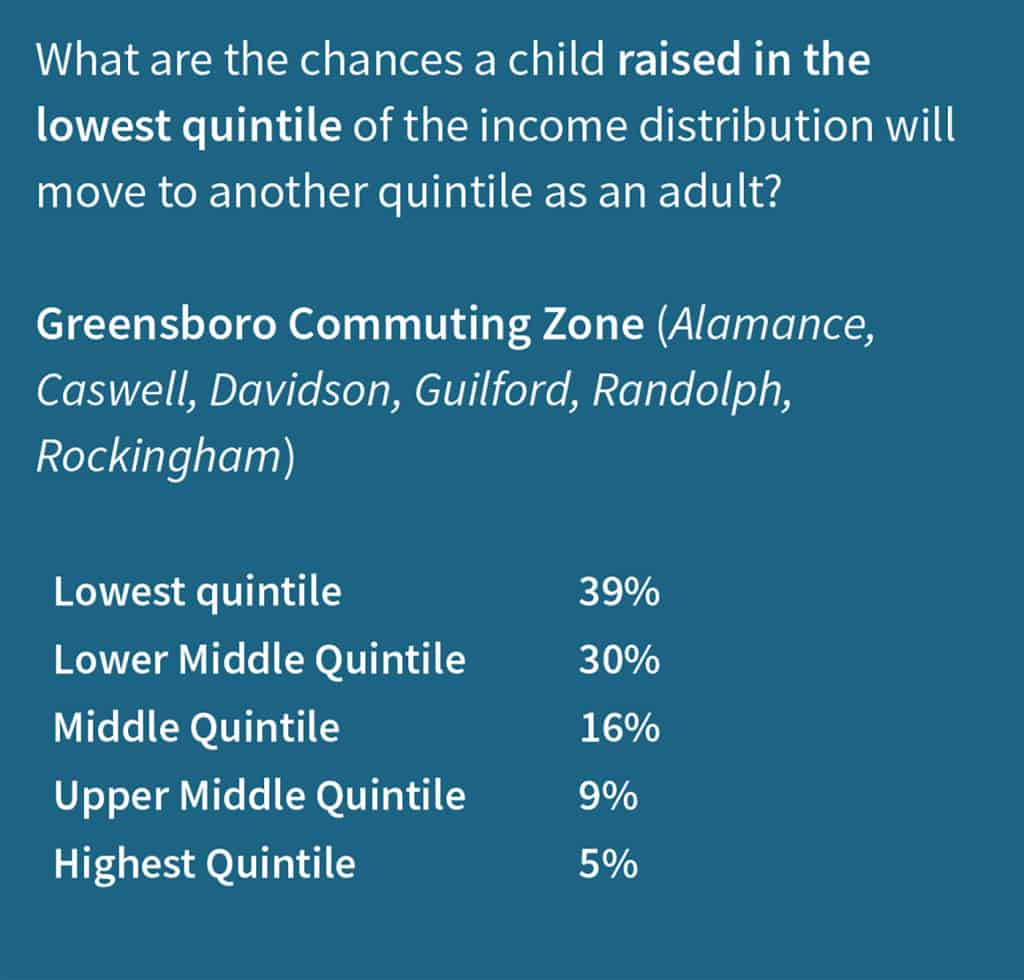

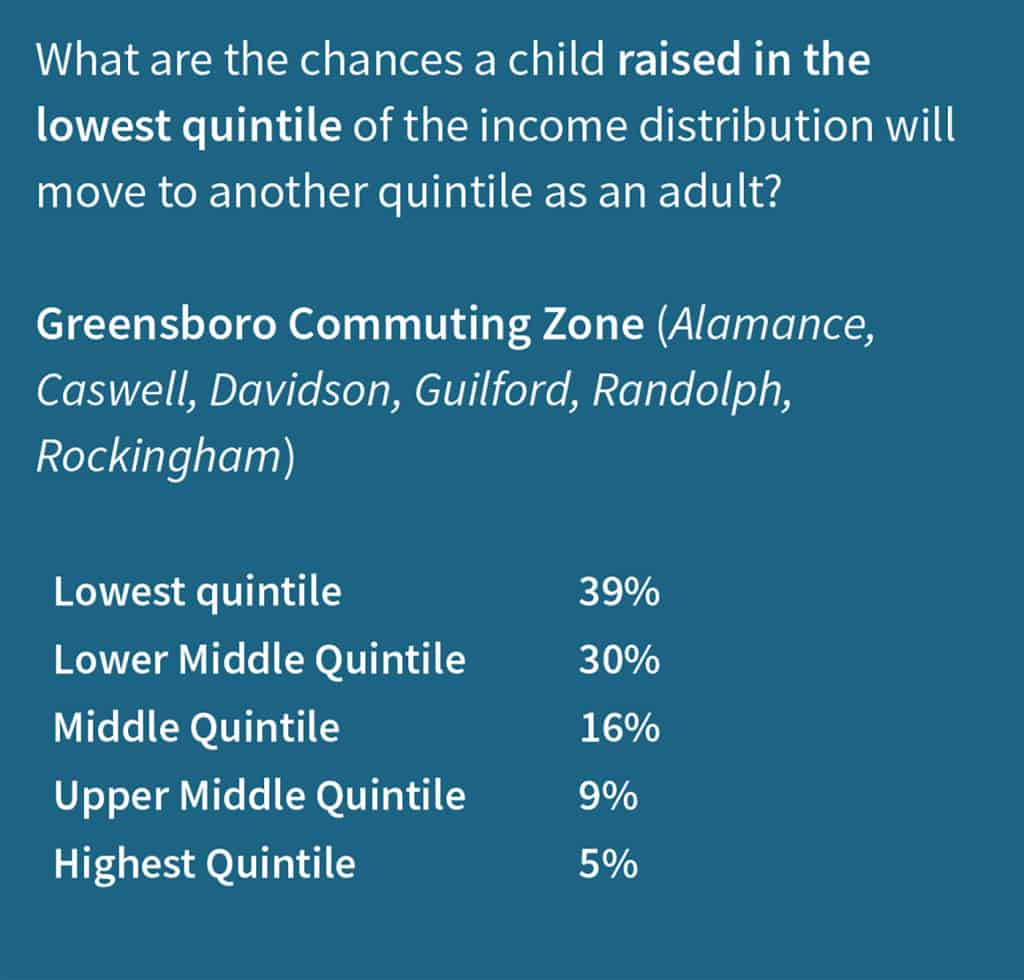

For so long, Guilford residents did not need higher education to take care of their families. Community members were able to support their families with jobs in factories—jobs that did not require much education. The last of these jobs left at the turn of this century. Between 2001 and 2014, the Greensboro-High Point MSA lost 17,000 jobs, most significantly in production and construction occupations, while the county’s population grew by nearly 20 percent during this same time period. Since 1990, Guilford County has lost 25,000 manufacturing jobs, representing more than a quarter of its total manufacturing job base. 3 Residents with limited education were left with far fewer opportunities for employment. Guilford did not just have a leaky education to career pipeline—the pipeline was broken.

Educators are working hard to make sure all students make it to and through Guilford’s postsecondary institutions. But much of classroom success depends on factors outside of the classroom. For years, Guilford ranked in the top five in the nation in the Food Research and Action Center food insecurity rankings. In 2014, it reached number one on that list. Patrice Faison, 2012 North Carolina principal of the year for Oak Hill Elementary School and current principal of Page High School, knows this affects her school: students cannot concentrate in class when they are worried about their next meal. And that’s not the only concern Faison has for her students. Many of her students also deal with unstable housing situations and lack of familial support. Faison says, “I rearranged my budget so that we could afford a full-time social worker to help students and their families work through trying situations.”

“I rearranged my budget so that we could afford a full-time social worker to help students and their families work through trying situations.” — Patrice Faison, 2012 North Carolina principal of the year and current principal of Page High School

Guilford County community members believe that working in partnership will pull them out of their economic decline. According to Winston McGregor, executive director of the Guilford Education Alliance, when manufacturing and other employers left the area in droves, local governments and organizations “partnered out of necessity.” Cross-sector partners had to align resources because the problem was too big for one institution to solve, and no individual institution had the resources to make progress alone. In 2011, the Community Foundation of Greater Greensboro and the United Way of Greater Greensboro realized they had to make it easier for people to move along the education-to-career continuum. So they created a community taskforce, Greensboro Works, focused on developing a shared vision for the economic success of the community. Greensboro Works recommended leaders work in partnership to address three community concerns: workforce training, postsecondary degree completion, and family economic success. (Even though the taskforce is called Greensboro Works, many of the efforts reach the entire Guilford County community.) According to Tara Sandercock, senior vice president for the Community Foundation of Greater Greensboro, “The taskforce decided the most strategic way to address those three issues is to invest in research and development to align Guilford with national initiatives, joining learning networks, and leveraging national funding to support these efforts (Lumina Foundation, National Fund for Workforce Solutions, Walmart Foundation, and others) with other communities also trying to rebuild and grow their workforces.”

Addressing Poverty

The United Way of Greater Greensboro realized that poverty rates were moving in the wrong direction and wanted to understand the root cause. They identified six critical populations who face the most severe headwinds in their community: female heads of household, families with young children, men and boys of color, immigrants, seniors, and veterans. They found significant intergenerational poverty, both systemic and institutional, among these populations. In 2015, after spending two years researching best practices and using Annie E. Casey Foundation and Aspen Institute Family Economic Assessment frameworks to identify strengths, challenges, gaps, and opportunities for Guilford families’ economic success, the United Way and 18 partners, established the Family Success Center, a place-based, integrated response aimed at lifting families out of poverty. Michelle Gethers-Clark, the president and CEO of the United Way of Greater Greensboro, explained the meaning behind the Family Success Center name:

- Family: the nucleus of the community

- Success: center participants are successful

- Center: a place for the community to go

Currently, the program is serving more than 100 families. They are paired with success coaches who develop customized goals for each family member. When families meet defined milestones, they receive incentives, such as deposits in college savings accounts. “Family participants will be accountable for their success that leads to financial independence,” says Gethers-Clark. “When people feel successful, the community is successful.”

“When people feel successful, the community is successful.” — Michelle Gethers-Clark, president and CEO, United Way of Greater Greensboro

Saying Yes to Education

Maurice “Mo” Green, former superintendent of Guilford County Schools and now executive director of the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, says, “I want to create a new normal for higher education expectations in my community—one where everyone sees college as the next step.” But first, students must make it to high school graduation. The school district has several initiatives to assist students in getting there, many specifically designed for first-generation and at-risk students. Many of these interventions put students in defined cohorts with graduation coaches, early colleges, middle colleges, and specialized academies. The hard work is paying off; this past school year the district nearly had a 90 percent graduation rate. But the district is looking at other metrics besides graduation to ensure students are ready for that next step. The district aims for success in ACT, Advanced Placement, and International Baccalaureate testing, dual enrollment passage rates, the number of students who complete career certifications while in high school, and the number of graduates who meet the minimum entry requirements for the UNC system. Green believes they can increase success in all of these metrics, but finding the necessary resources is a struggle. He determined that the number one question facing policy leaders in North Carolina is, “Are you going to fund the education system adequately to get the results we need?”

“I want to create a new normal for higher education expectations in my community—one where everyone sees college as the next step.” — Maurice “Mo” Green, former superintendent of Guilford County Schools and executive director of the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation

Securing those resources is seen as a community concern in Guilford. Dr. Franklin Gilliam, chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro (UNCG), talks about the “shared fate” of the university and the community: “When UNCG succeeds, the community succeeds; and when the community succeeds, UNCG succeeds.” Others in the community believe this, too. In 2002, the High Point Community Foundation, the Community Foundation of Greater Greensboro, and the Cemala Foundation joined forces to create the Guilford Education Alliance (GEA). GEA, with the tagline “educational success is a community responsibility,” serves as a fundraiser, an advocate, and a backbone organization for several educational efforts across the community. So when Guilford decided to begin conversations about joining Say Yes to Education, the infrastructure already was in place. In 2013, GEA, the Community Foundation of Greater Greensboro, the High Point Community Foundation, and Guilford County Schools first explored bringing national initiative “Say Yes to Education” to Guilford, thus beginning a period of research and fundraising. After a year and a half of hard work, Guilford was selected as a Say Yes to Education community in September 2015. Say Yes galvanizes communities around three main goals. First, Say Yes helps communities build local endowments that provide last-dollar tuition scholarships so public school graduates can afford and complete a postsecondary education. Second, Say Yes works with the community to build student support that help students every step of the way toward completion of a postsecondary degree. Third, Say Yes works with school leadership to ensure students are on the path to academic success.

To fund the local endowment and demonstrate capacity to implement a Say Yes partnership, Say Yes challenged Guilford to raise $28 million in commitments. Guilford residents exceeded that goal by raising $32.5 million by launch. That total has since grown to $34.5 million. They have set a goal of $70 million for the endowment. “The whole effort is what we call innovative disruption,” says McGregor. “We’re building new systems, targeting investments, and looking differently at how we can align a variety of resources in our community to ensure success for students. This will benefit students, families, and our entire community for generations to come.”

“This will benefit students, families, and our entire community for generations to come.” — Winston McGregor, executive director, Guilford Education Alliance

Say Yes tuition scholarships work in different ways. All Guilford County high school graduates regardless of income are eligible for last-dollar tuition scholarships for in-state public colleges and universities (including one-, two-, and four-year degree and certificate programs). There are also more than 100 private colleges and universities that offer last-dollar tuition guarantees for students with household incomes at approximately $75,000 or less. For students above the income cap, the local endowment provides up to $5,000 to help offset cost of tuition.

Say Yes is a commitment to all Guilford high school graduates that they will have tuition assistance, but it is more than dollars for college. The program provides wraparound services (e.g., mental health counseling, tutoring, and afterschool programs) for students, starting in elementary school, to expand children’s individual college-going aspirations and see college as a place where they belong. McGregor explains that Say Yes provides a wide, research-based path for all students, pushes students along the path with support services, and pulls students over the finish line with the promise of the scholarship. With Say Yes, everyone is accountable to the same success goal: postsecondary credentials that lead to family-sustaining employment, aiming for the new normal Mo Green hopes for his community.

Guilford Technical Community College (GTCC) is part of another national initiative, “Completion by Design,” a Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation initiative that works with community colleges to increase completion for low-income students before age 26. GTCC administrators believe Say Yes fits nicely with Completion by Design. The intrusive advising offered through Say Yes will help educators find out what students’ challenges are and offer support to face those challenges. Ed Bowling, executive director of Completion by Design, says, “This should reduce the number of developmental education students [those who need remedial course work] because they will be more college-ready.”

Say Yes builds on the Greensboro Works strategy of joining national learning communities, including another Guilford initiative, Degrees Matter. Focusing on community members who started college but did not complete, Degrees Matter is a Lumina Foundation-funded initiative, in partnership with the Community Foundation of Greater Greensboro and the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and Guilford County’s seven other institutions of higher education. In addition to Guilford County, Lumina funded 19 other communities in The Graduate Network focused on adult college completion. Lumina also asked Degrees Matter to join the Community Partnerships for Attainment initiative, an effort to deepen the impact of cross-sector, place-based strategies to increase higher education attainment. Steve Moore, executive director of Degrees Matter, says that receiving funding from Lumina provided credibility for their work and helped them secure funding from other foundations like the John M. Belk Endowment. With an intentional focus on immigrants, men of color, veterans, and single moms, leaders of Degrees Matter talk about the importance of FIT— finances, institutional support, time—when matching students with the right college. They already work with some local businesses, including Bank of America and Cone Health, and they plan to scale up these efforts and connect to other employers, like the City of Greensboro. Moore says that studies have shown that local employers receive a $1.40 return on every dollar invested in college tuition reimbursement.

Connections to Employers

Guilford County followed the Greensboro Works strategy of learning from national models while trying to find an answer for business growth. Opportunity Greensboro, a group of leaders from businesses, foundations, and higher education institutions, developed the Union Square Campus for healthcare professions, based on Campus Philly. Campus Philly is Philadelphia’s effort to jointly improve the city’s economic development system and college student retention rates. Opportunity Greensboro members believe this national model will “transform Greensboro’s wealth of educational assets into economic success.”4 UNCG, NC A&T, GTCC, and Cone Health will share programming, lab space, and equipment, resulting in considerable cost savings. Leaders hope this will stimulate further economic development in the Union Square area. They think this partnership strategy can be replicated in other industries across the county and throughout the state.

“Good jobs with benefits would eliminate the need for United Way services. And that’s a good thing,” says Bobby Smith, executive director of the United Way of Greater High Point. Many community leaders are working to bring those good jobs to Guilford. The Greensboro Works recommendations include making the community a National Fund for Workforce Solutions (NFWS) site to develop a sector-based partnership to support innovative approaches to workforce demands. The Triad Workforce Solutions Collaborative is the realization of those recommendations. Donna Newton, executive director for the Collaborative, describes the effort as “a loose, organic group of business leaders, educational institutions and support organizations interested in Guilford workforce development.” Newton says the biggest benefits to being an NFWS site are the opportunities to apply for exclusive grants and to learn from other communities. In the past two years, the Collaborative has: developed a youth apprenticeship program; received a Social Innovation Fund grant from NFWS to work with local career centers to help people obtain manufacturing certificates and employment; worked with Walmart on building the supply chain management workforce; and now is attempting to reinvigorate career and technical education programs in partnership with local employers.

“Good jobs with benefits would eliminate the need for United Way services. And that’s a good thing.” — Bobby Smith, executive director, United Way of Greater High Point.

Individual students also see a return on investment in education-employer connections. GTCC is using industry data to review its programs and develop stackable credential pathways for students. Advisors help students see that getting an associate’s degree is not just a two-year process but a series of milestones with credentials and degrees before and beyond the associate’s. GTCC is creating these pathways in areas of high-demand for skilled workers. The college recently received a United States Department of Labor grant to help displaced, socioeconomically challenged workers obtain jobs in the aviation industry. Most of these students are employed upon completion of the program.

Economic Vision

The goal of Greensboro Works is to create a shared vision for the economic success of the community. In November 2015, the county took a huge step in developing that vision. The Guilford County Board of Commissioners, Greensboro City Council, and High Point City Council passed a resolution to create the Guilford County Economic Development Alliance (GCEDA). Leaders hope this new entity will usher in a culture of cooperation among the cities and the county in economic recruitment efforts. The Alliance will serve under a leadership board and also will have a Business Advisory Council with 12 members, including the chair of the Workforce Development Board and the president of GTCC. According to High Point Mayor Bill Bencini, “We’ve learned how to develop trust between the three jurisdictions. This partnership is about getting to the point where we could develop a model to institutionalize cooperation between all three of us.”5

While several communities affected by the 1980s and ’90s decline in manufacturing are still trying to figure out their comeback, Guilford County has taken several steps up the staircase to economic success. Through philanthropic and private investments, the Guilford County community has succeeded in having Greensboro Works join national learning communities. This strategy is helping the county move toward system-level change through sustainable partnerships, community commitment to educational and economic success, and data-driven decision-making.

But this success leads to even more questions. As the energy from and hope for Say Yes continues to build in Guilford, community leaders are concerned about how to keep the momentum going for other community initiatives. They want to understand how to help economically disadvantaged, at-risk students see that this $70 million endowment is for them and not just for the middle-income students on the other side of town. The community also must grapple with how to keep Say Yes recipients in Guilford for college or get them to return after college graduation by providing them with attractive employment options. And with two large cities in one county, they must ensure that both Greensboro and High Point are continuing to move in the same forward direction: providing much needed family-sustaining jobs for community members. It’s hard to determine what success will look like for the new GCEDA, but Mark Sutter from the Triad Business Journal believes “a win for them would be to look back and say ‘we were able to put our best foot forward’ and weren’t fighting over [a business prospect] and that they had a unified approach. I think there’s a lot of faith that a unified approach will bring the best results.”6

Guilford County is moving toward a vision that diminishes the effects of poverty and exclusion, so the community can enjoy the health and prosperity gained when everyone’s success matters. In robust partnerships with education leaders, community leaders, employers, and their neighbors, they are moving in this direction. But it will take time. As the Rev. Odell Cleveland, chief administrative officer for Mount Zion Baptist Church in Greensboro says, “Partnerships are built at the speed of trust.”

“Partnerships are built at the speed of trust.” — Rev. Odell Cleveland, chief administrative officer, Mount Zion Baptist Church

NORTH CAROLINA’S ECONOMIC IMPERATIVE: BUILDING AN INFRASTRUCTURE OF OPPORTUNITY

Part 1–Introduction

Part 2–Cultivating aspirations: Vance, Granville, Franklin, and Warren Counties

Part 3–Partners at the speed of trust: Guilford County

Part 4–Recovery through collaboration: Wilkes County

Part 5–Landscape defines opportunity: Western North Carolina