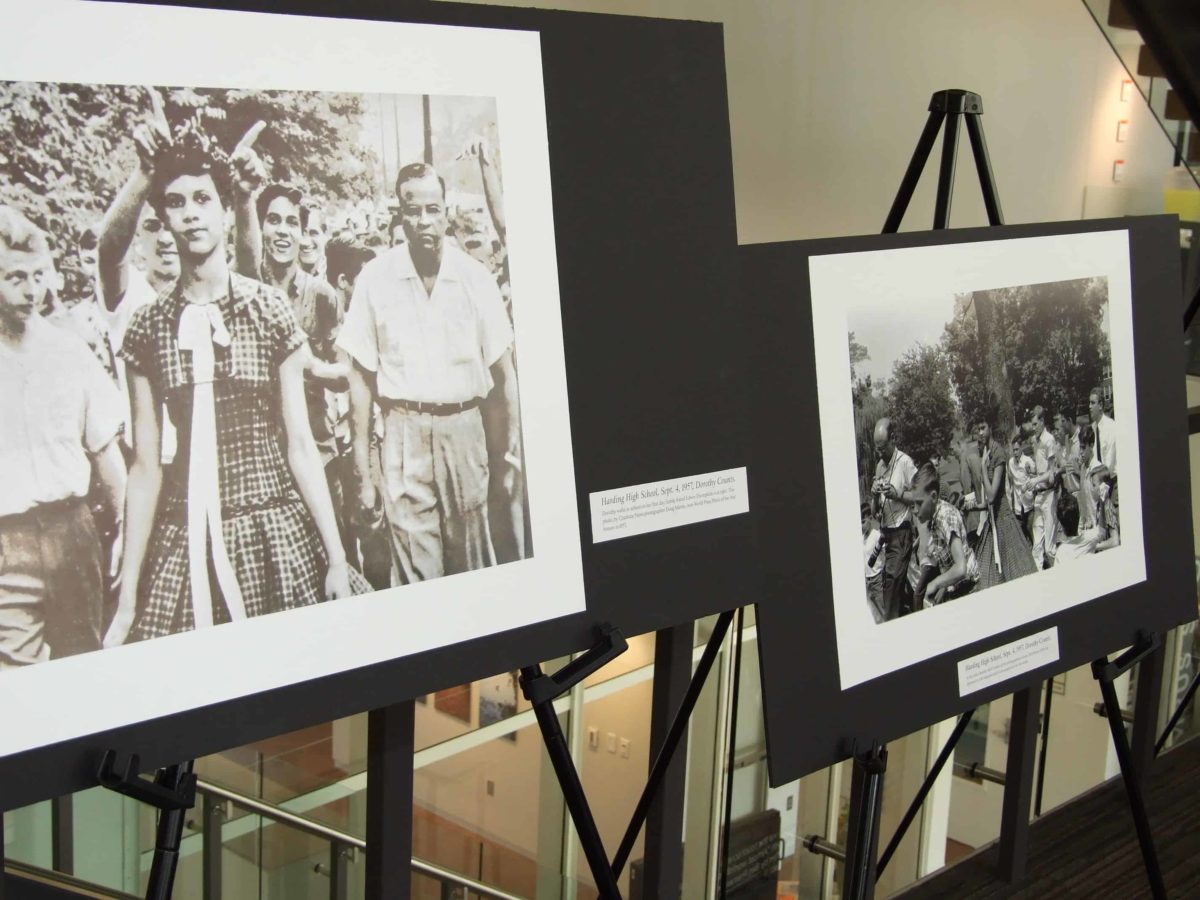

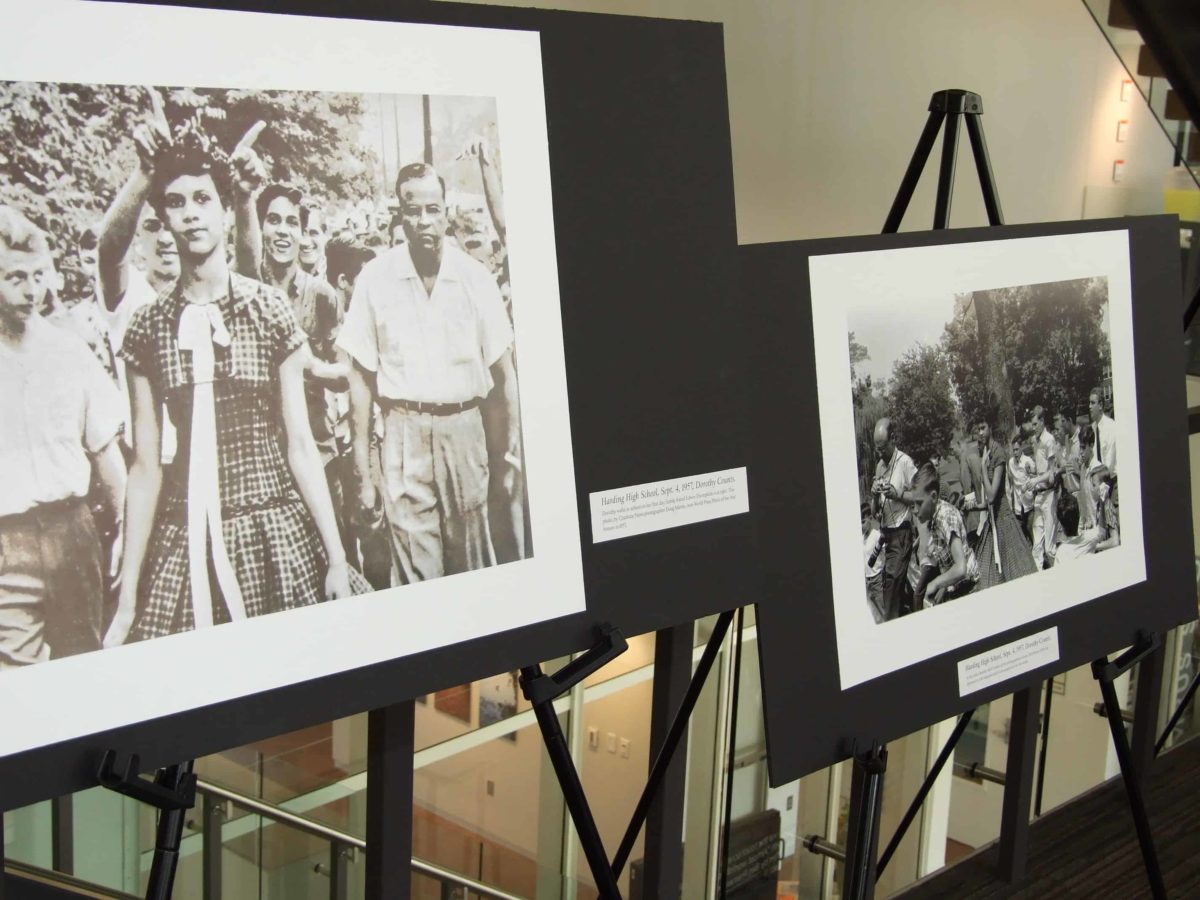

In the famous black-and-white photo, Dorothy Counts, in a plaid dress with sunglasses dangling from her neck, holds her head high. White men and boys are behind and beside her, jeering and pointing. The photo, taken by Charlotte Observer photographer Don Sturkey, is from September 1957, when Counts became the first black student to attend Charlotte’s Harding High School.

The photo became iconic of Charlotte’s central role in a decades-long discussion about the intersection of race and public education. So it was no surprise to see a copy of the picture displayed on a black easel, alongside others, at a public conversation on the desegregation of Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools last week.

The event, sponsored by UNC Charlotte, drew a standing room only crowd of more than 300 people. It began with a discussion of Charlotte’s past, offered by Frye Gaillard, a journalist who covered desegregation for The Charlotte Observer, and later wrote a book, The Dream Long Deferred, on the subject.

“There were people in Charlotte from the very beginning,” Galliard said, “who wanted to see constructive change even if they weren’t quite sure what to make of it.”

Despite the angry mob that Counts faced in 1957, and despite the firebombing of civil rights leaders’ houses in 1965, Gaillard said many Charlotteans knew desegregation could help the city. “There was sense of enlightened self interest from the get-go.”

Still, it wasn’t easy.

The past

Gaillard recounted the iterations of the historic Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education lawsuit, which would lead to busing students for the purposes of integration. When the suit came about, in the mid-1960s, the first federal judge who heard it said, essentially, that Charlotte was doing just fine when it came to race and education. He ordered a few minor tweaks, but nothing major.

Of course, the case would become much more consequential after Judge James McMillan ruled, in 1969, that CMS was not, in fact, integrated. He ordered the school board to come up with a desegregation plan that could include busing. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld McMillan’s ruling in its landmark 1971 decision.

Gaillard called the ensuing decade, from the mid-1970s to the mid-1980s, a “golden” period for Charlotte, as the community found a way to embrace integrated schools. “There was no way for the community to avoid what the judge was asking,” he said. “The decision was framed this way, by leaders of all shape and opinion: ‘We either have to make this work or watch our schools be destroyed.’”

But in 1984, President Ronald Reagan, wildly popular and running for re-election, held a rally in South Charlotte at which he commented on busing. He called it a social experiment that had failed.

“In that moment, there was icy, stony silence in that crowd,” Gaillard recalled. “A desegregated school system was part of Charlotte’s identity, and a point of pride in the community, and the good publicity Charlotte got for that was one of the things driving growth, I think.”

However, Reagan’s comment opened the doors to conversation about the merits of busing. “It tended, when the president said that, to legitimize discussion and questioning of the desegregated school system and busing as the means to achieve that, and it got noisier and noisier as time went by,” Gaillard said.

By the 1990s, there was an open revolt against busing, and student assignment. In 1997, a parent, Bill Capacchione, sued CMS, arguing that his daughter was denied entrance to a magnet school because she was white. In 1999, U.S. District Judge Robert Potter ruled CMS was fully integrated and that it could no longer use race in determining student assignment. It was an historic moment.

After the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld Potter’s ruling, and after the Supreme Court decided not to hear the case, CMS entered a new era of neighborhood schools.

The present and future

All of this history, Gaillard said, is necessary to understand where Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools is today.

Amy Hawn Nelson, an education researcher who leads UNC Charlotte’s Institute for Social Capital, said the arguments from the original Swann case—that segregated schools harm poor and minority students—apply today. Just as they did in the 1960s, housing patterns in Mecklenburg County today break down along racial and socio-economic lines.

“I find it disheartening that here we are, 45 years later, making the same argument.”

Segregated schools, she said, lead to inadequate facilities, lack of access to high level coursework, poor teacher quality, and lower graduation rates. “The outcomes are clear. Segregated schools don’t work.”

Nelson said there are plenty of challenges inherent in desegregation. “I’m not one of those people who looks at the time of desegregation as one continuous chorus of kumbaya,” she said. “But it appears to work better than anything else we’ve tried. In many ways for our community, desegregation has been a rejected success.”

Her research, including a book project on race and education in Charlotte, highlight troubling statistics. A third of Charlotte-Mecklenburg schools today are segregated by poverty, Nelson said. Half are segregated by race. And a fifth are hyper-segregated by race.

She said CMS is approaching pre-Swann levels of school segregation.

“Our children are increasingly isolated,” she said.

But it’s not just a racial issue. Indeed, Nelson said, the income achievement gap is nearly twice the size of the black-white achievement gap. “While racial segregation is important, poverty matters. Any effort to improve school quality should avoid hyper-segregated schools of poverty.” Roughly 51 percent of CMS students, or about 83,000 children, live in poverty.

Although Nelson made a case for more fully integrated schools, she said busing might not be the way to do it. “This conversation is not about busing,” she said. In fact, CMS buses more than it did at the height of desegregation in 1984. It saw an increase in busing after the end of court-ordered busing in 2002. “We bus now for choice.”

More than anything, she argued, it’s important for the community to recognize the lingering effect of segregation on our public education system. The conversation, Nelson said, must continue.

“The choices of yesterday and the choices of today will impact our tomorrow.”

See Nelson’s presentation here: