As EdNC completes its third year with a goal to accentuate the “public in public policy,” let us ponder a couple of signs of the times:

- More than half of Americans say the internet-driven proliferation of news sources makes it harder for them to be informed. That finding comes from a new survey by Gallup and the Knight Foundation, which also shows that 54 percent of Democrats hold a favorable opinion of the news media, while 68 percent of Republicans view the news media unfavorably.

- The Brookings Institution’s Brown Center on education published an essay this week, drawing on survey data, reporting “striking’’ differences across racial and ethnic lines on whether children can get a quality education. “While many African-Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans see their children as disadvantaged by the school system as a consequence of their race or ethnicity, most white Americans and Asian-Americans do not share this concern,” says the essay.

Every week, it seems, additional evidence emerges of a nation politically polarized and geographically divided, with a pervasive distrust of public, private and nonprofit institutions. North Carolina, too, seems to have a social contract in disrepair.

How, then, can public deliberation and participation be restored to developing public policy?

In another fractious decade half a century ago, North Carolina served as a model for an effort to bring people, previously shut out, into public decision-making. The federal Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 required “maximum feasible participation’’ by the people, many of them poor and powerless, in community development, early education and other anti-poverty assistance directed to their towns and cities. During its five years of life in the 1960s, The North Carolina Fund pioneered efforts to make “maximum feasible participation’’ a reality.

Especially in the segregated South but also in big cities of the North, “maximum feasible participation’’ encountered stiff resistance from state and local officialdom — from powerful people who didn’t want to share control of government funding. So contentious did the term become that it has long fallen out of use. Still, the concept ripples across the land in local citizen-action councils, in community development organizations and in the “populist’’ movements of both the political left and right to claim public support for an agenda.

“As implied in the word democracy, the role of the demos (the citizenry) is central,” writes David Mathews, president of the Ohio-based Kettering Foundation. “We the People are sovereign in the U.S. Constitution, yet, as noted, people have often been criticized for not exercising sound judgment.”

Mathews is a former president of the University of Alabama and former secretary of health, education and welfare under President Gerald Ford, a Republican. At Kettering, Mathews has written about and sponsored research on civic engagement. In a recent essay, he says, “Given the problems our political system is having now, rethinking civic education couldn’t be more urgent.”

Yes, he writes, providing citizens with more factually correct information is important, but “the most important political decisions are often about what is right or should be done.” There is, he says, “no substitute for doing the hard work of making shared judgments.”

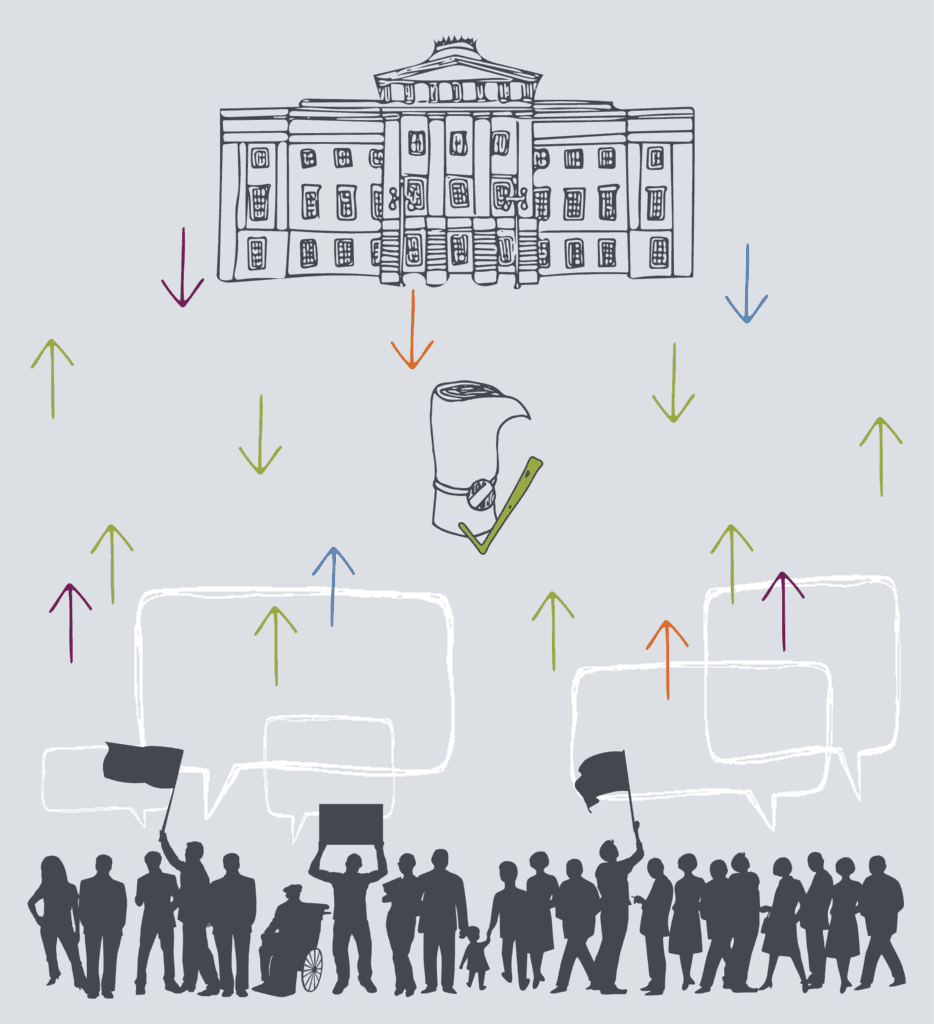

Reaching for shared judgments would require both bottom-up and top-down dynamics. Sovereign citizens need channels to voice their needs and aspirations. The nation, states, and communities also need the research of scholars, the expertise of policy analysts, the professionalism of government staffs, and, above all, the informed and courageous initiatives of major civic and political leaders, skilled in coalition-building and in articulating a vision.

EdNC accepts its own role in fostering both bottom-up and top-down dynamics, proclaiming that “our work encourages informed citizen participation and strong leadership in behalf of the school children of North Carolina.”

Since its launch in mid-January 2015, EdNC has strived to meet the challenges of assembling an audience in the tumultuous online ecosystem, serving as a credible, nonpartisan source of news, and providing a forum for debate on education issues in North Carolina. Along the way, EdNC absorbed the N.C. Center for Public Policy Research, instituted Reach NC Voices, and added First Vote to its repertoire.

With its journalistic, policy research and public engagement tools, EdNC has begun its fourth year better prepared and more determined to act as a catalyst for the “hard work’’ of public deliberation and decision- making.