|

|

A new report from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute studied whether evaluations of charter applications by North Carolina’s former Charter School Advisory Board (CSAB) were good predictors of the success of new charter schools.

North Carolina removed its statewide cap of 100 charter schools in 2011. The institute’s report tracked charter applications after the cap was removed through before the start of the pandemic. During this time period, there were 179 applications, the report says, including 53 approved charters and 43 schools that successfully opened.

Importantly, this means the report includes data from when the State Board of Education acted as the sole authorizer of charters, approving or denying recommendations made by the CSAB. Following legislation passed in August, the advisory board no longer exists. It is now the Charter School Review Board (CSRB). The law now grants the review board sole authority to approve or deny charter applications, renewals, and material changes.

The report uses data on application ratings and votes from the CSAB.

Published on March 19, 2024, the institute’s report paints a complicated picture.

First, schools that a higher share of CSAB reviewers voted to approve, the report found, were more likely to open on time than other approved schools, but no more likely to meet their enrollment targets.

Second, charters that more CSAB reviewers approved performed slightly better in math, but not in reading.

Third, evaluation ratings by the CSAB for “specific application domains mostly weren’t predictive of new schools’ success, but the quality of a school’s education and financial plans did predict math performance.”

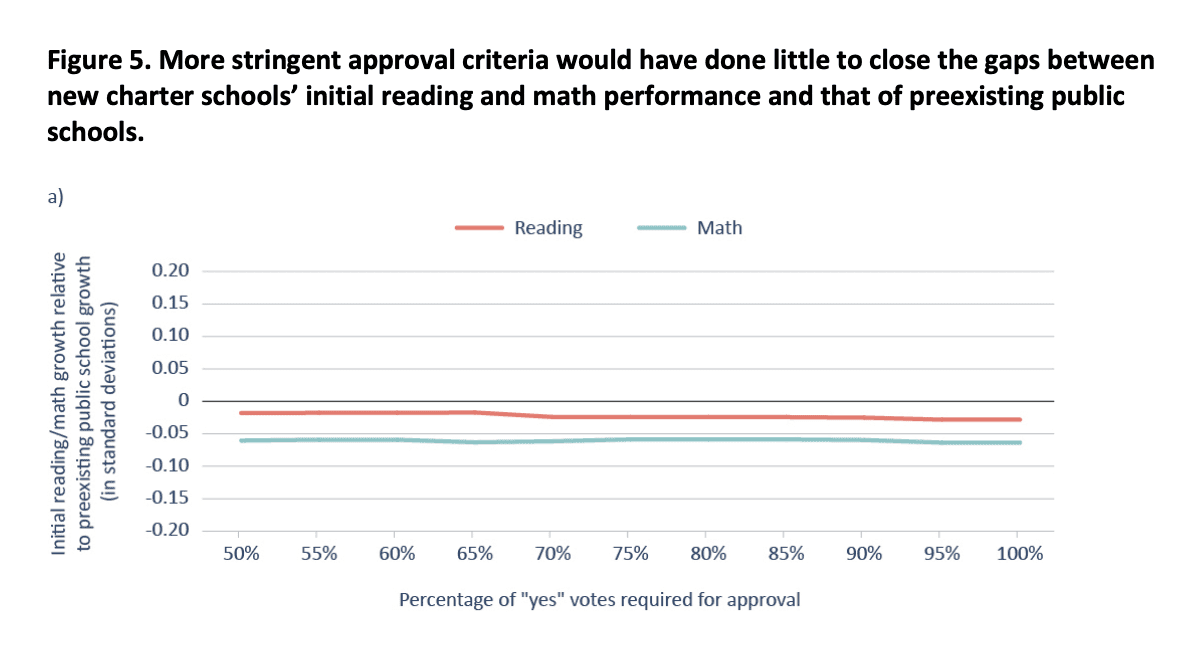

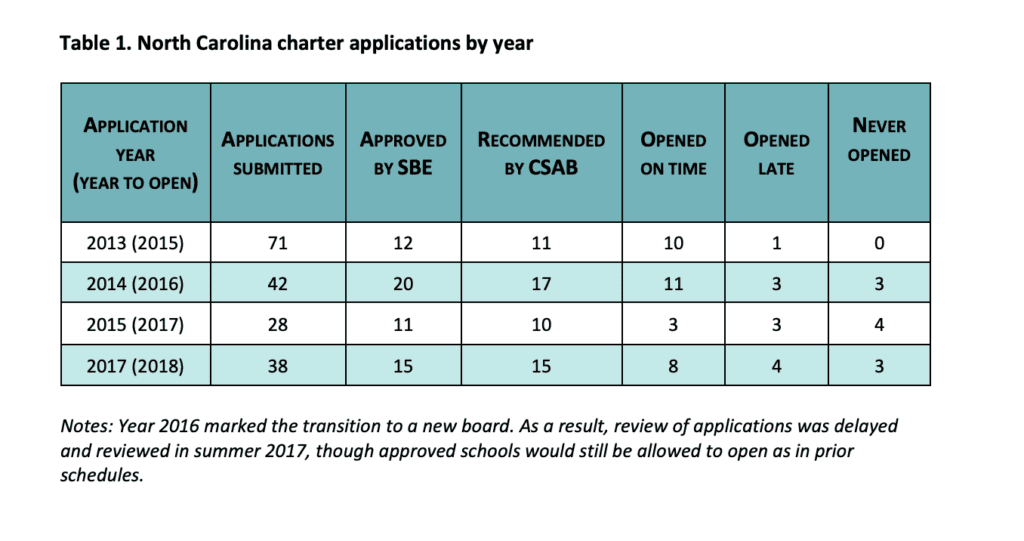

And finally, “simulations show that raising the bar for approval would have had little effect on the success rate of new schools.”

According to the report, the main takeaways for charter authorizations moving forward, include:

- Authorizers should pay close attention to applicants’ education and financial plans. “The quality of these plans significantly predicts the resulting schools’ math performance (unlike other elements of the application, such as the perceived quality of a school’s mission statement),” the report says. “Based on Fordham’s experiences as an authorizer, our sense is that’s no coincidence, as instructional prowess and budgetary competence are quite simply ‘must-haves.'”

- Authorizers should incorporate multiple data sources and perspectives.

- Authorizers must continue to hold approved schools accountable for their results.

“We know that the quality of charter schools, like the quality of individual teachers, varies drastically once they are entrusted with the education of children,” the report says. “So, if we can’t reliably weed out low performers before they are approved, the only surefire way to ensure that charters fulfill their mission is to intervene when their performance consistently disappoints.”

In North Carolina, charter schools can have their charter revoked for several reasons, including designation as a continually low-performing charter school.

In addition, DPI’s website says charter school renewal requests can be denied if “student academic outcomes for the immediately preceding three years have not been comparable to the academic outcomes of students in the local school administrative unit in which the charter school is located.”

The institute’s report says that such measures are necessary “so long as a minority of approved charters underperform.”

The Fordham Foundation, the affiliated foundation for the institute, acts as a nonprofit authorizer to 10 charter schools in Ohio. The institute’s report repeatedly notes its research is designed ensure higher quality performance of charter schools.

Read more on charter schools

Methodology of report

The report analyzed five domains from North Carolina charter school applications:

- Mission and Purposes. This described the mission, purpose, and goals of the proposed charter school, as well as the targeted student population.

- Education Plan. This described the proposed charter school’s standards, curriculum, and instructional design, including specific instructional plans for “at-risk” students and students with disabilities, as well as its discipline policies.

- Governance and Capacity. This described the structure and responsibilities of the governing organization (e.g., school board); the projected staff required including hiring, management, evaluation, and professional development plans; plans for enrollment, marketing, and parental and community involvement.

- Operations. This described school plans for transportation, school lunch, insurance, health and safety, and facilities.

- Financial Plan. This described the budget for the school, including expected income and expenditure projections for the first five years of operation.

According to the report:

During the study period, which stretches from the abolition of the statewide cap to the arrival of Covid-19 (i.e., from 2012–13 to 2018–19), charter applications were first submitted to the state’s Office of Charter Schools, where they were evaluated for completeness and then reviewed and assigned a rating of “pass or fail” for each domain by up to fourteen external evaluators, who were selected by the Office of Charter Schools based on their experience operating existing charter schools. Next, members of the CSAB reviewed applications and external-reviewer ratings and conducted first-round “clarification interviews” with applicants, the most promising of which received a second “full interview.” Finally, based on the contents of the application, the external reviewers’ ratings, and the information gathered in interviews, CSAB members voted on whether or not to recommend the application for approval, with members who had a conflict of interest recusing themselves. Applications that received a simple majority of “yes” votes (51 percent) were forwarded to the State Board of Education (SBE), which accepted CSAB’s recommendations over 90 percent of the time.

On average, the report found, 10 CSAB members voted at each application vote with at least seven CSAB members participating in each vote.

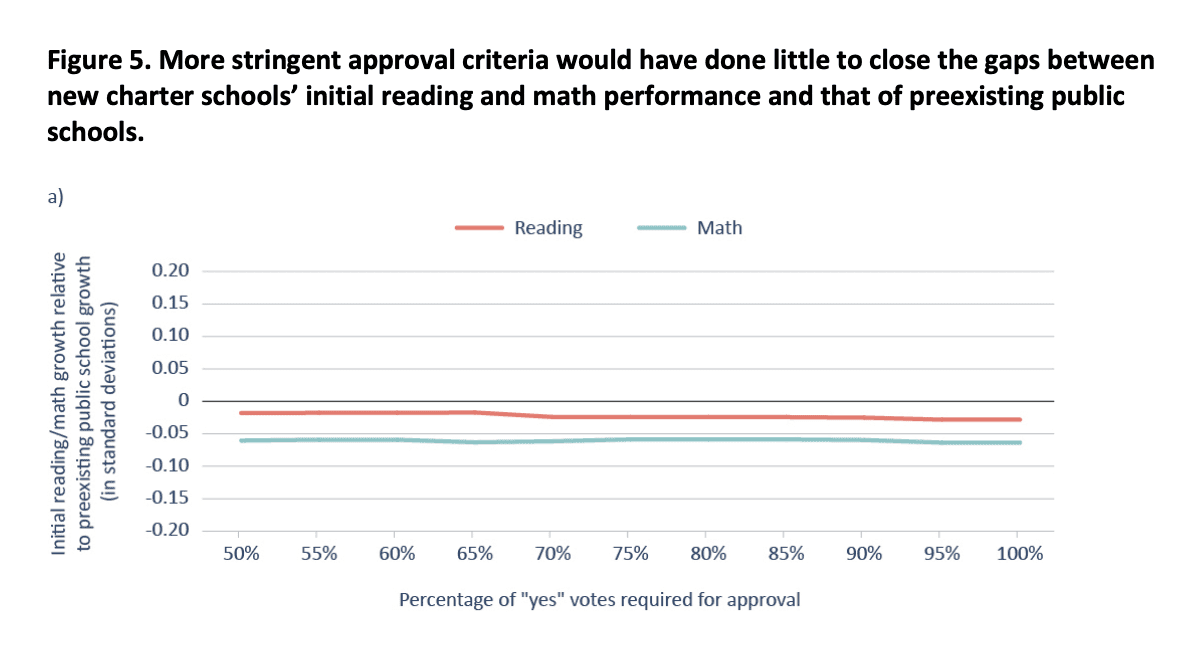

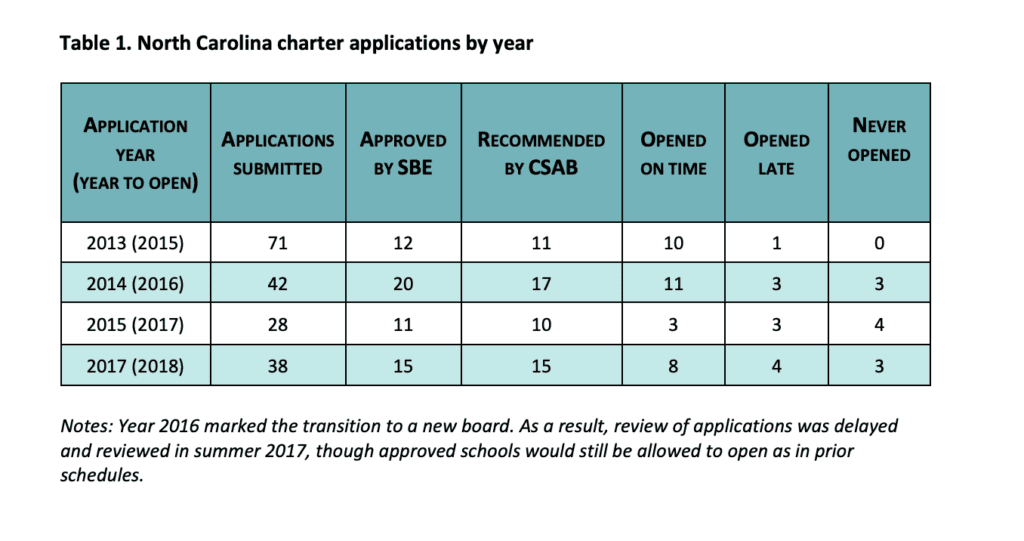

Here is a look at the charter applications recommended to be approved by the CSAB board. As you can see, the first year after the cap was removed saw the highest number of applications submitted, along with the lowest acceptance rate.

“Perhaps as a result of this low approval rate, in the following three years, fewer applications were submitted, and CSAB’s recommendation rate increased,” the report says. “On average, CSAB recommended approximately one-third of the applications it received for approval, and SBE continued to approve nearly all the applications recommended by CSAB.”

On-time opening rates “decreased significantly for later cohorts,” the report says.

Along with analyzing application domains, the report also looked at seven years of student administration data from DPI.

Authorization process in North Carolina

As noted, previously charter school applications were reviewed by the CSAB, which made recommendations to the State Board of Education on which charters should be approved.

Now, the new CSRB has sole authority to approve or deny charter applications, renewals, and material changes. The State Board of Education can only review appeals of decisions by the review board.

“This action will make the application process more efficient, more cost-effective, and much more streamlined for all stakeholders involved,” Rep. Tricia Cotham, R-Mecklenburg, a primary sponsor of the bill, previously said of the legislation.

In June, State Board of Education Chair Eric Davis published a letter raising concerns about the legislation.

After the law passed, CSRB Chair Bruce Friend said the board’s work would continue as before.

“The mission and work of the CSRB basically remains the same — to ensure the existence of high-quality charter schools in the State of North Carolina,” he said. “High-quality charters benefit families and raise the level of academic excellence in North Carolina.”

North Carolina currently has 211 charter schools, according to DPI data.

Since the 2011 cap on charters was removed, the State Board of Education approved the creation of more than 100 schools, the institute’s report found. During the same time period, the State Board revoked charters for more than 25 “low-performing or struggling schools.”

The report characterized the State Board as “the exclusive overseer of one of the largest charter school portfolios in the land.”

According to the report, North Carolina is one of eight states with a single statewide authorizer for charter schools. Thirty-six states have some other combination of state and/or local authorizers.

In North Carolina, charter schools perform similarly to traditional public schools on average, based on school performance grade data.

The institute’s report suggests that paying more attention to the charter schools authorization process might lead to higher performance among charter schools across the country.

“Despite the growing pile of research that suggests charter schools outperform traditional public schools on average, the U.S. has too many mediocre or downright bad charters and too few truly excellent ones,” the report says. “Someday, perhaps, the guidance that empirical research provides to authorizers will make the process for approving new schools feel more scientific and less dependent on human judgment–or on that crystal ball that so often fails us. Until then, we’ll just have to take it one application at a time.”

Read the full report here.