This year has been a tumultuous time for the State Board of Education and the state Department of Public Instruction (DPI). To meet legislative budget cuts, the department had to lay off 40 staffers. Superintendent Mark Johnson announced a reorganization of the department following the resolution at the Supreme Court of the power struggle between he and the Board. And the Board saw the loss of vice chair Buddy Collins, a vocal member since he joined in 2013.

The State Board met this week and more changes are in the works. Here is what you need to know from the meeting.

Departures from the State Board

In an interview before the second day of the Board meeting Thursday, Chair Bill Cobey said September’s Board meeting will be his last. He submitted his letter of resignation to Democratic Governor Roy Cooper yesterday. He said there is no big reason why he is leaving, except that he wants to make way for new leadership.

At that meeting, Cobey, 79, said the Board will elect a new chair and vice chair since the terms for both leadership positions are up. Board member Eric Davis has been finishing out Collins’ term as vice chair since Collins resigned in March.

Cobey said overseeing the election of new leadership on the Board will be his last official act.

Cobey, a Republican, is a former athletic director of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, as well as a former member of the United States House of Representatives.

He has served on the Board since 2013. His term on the Board was officially supposed to end in March.

In his letter of resignation to the Governor, Cobey wrote: “It has been an honor to serve with such an outstanding group of board members who have faithfully made their first priority the interest of our public school children. I will miss serving with them.”

In a statement about Cobey’s departure sent via email yesterday, Governor Cooper said:

“Bill Cobey has been a dedicated advocate for public education in North Carolina and I am grateful for his tenacity working for our state’s school children and teachers. We have been fortunate to have had his leadership and his lifetime of knowledge.”

In an interview Friday morning, Board member Becky Taylor, who represents the Northeast education region of the state, said that she, too, has submitted a letter of resignation to the Governor. September’s meeting will also be her last.

Taylor has served since 2013. Her term is up in March, but she said she is leaving early because she is moving out of the district she represents.

While she acknowledged the past year and half has been tough as the Board has dealt with its legal challenge to Superintendent Mark Johnson, she said her resignation has nothing to do with any of that.

“I’m there for one reason,” she said. “I’m there to make decisions that I think will impact students in North Carolina.”

She said she hopes to continue having an impact on education going forward, working directly with schools and students.

Her memories of her time on the Board are fond ones she said as she highlighted the passion and professionalism of the staff at DPI, as well as the district superintendents in the region she represents.

And she said the State Board of Education is the best group she has ever worked with.

“I have absolutely loved working with the State Board of Education. I think we have the finest group of people sitting on that Board,” she said. “I’ve never worked with a group of people who are so passionate, so dedicated, and who really work together as a unit.”

Superintendent Mark Johnson discusses reorganization and reassures DPI

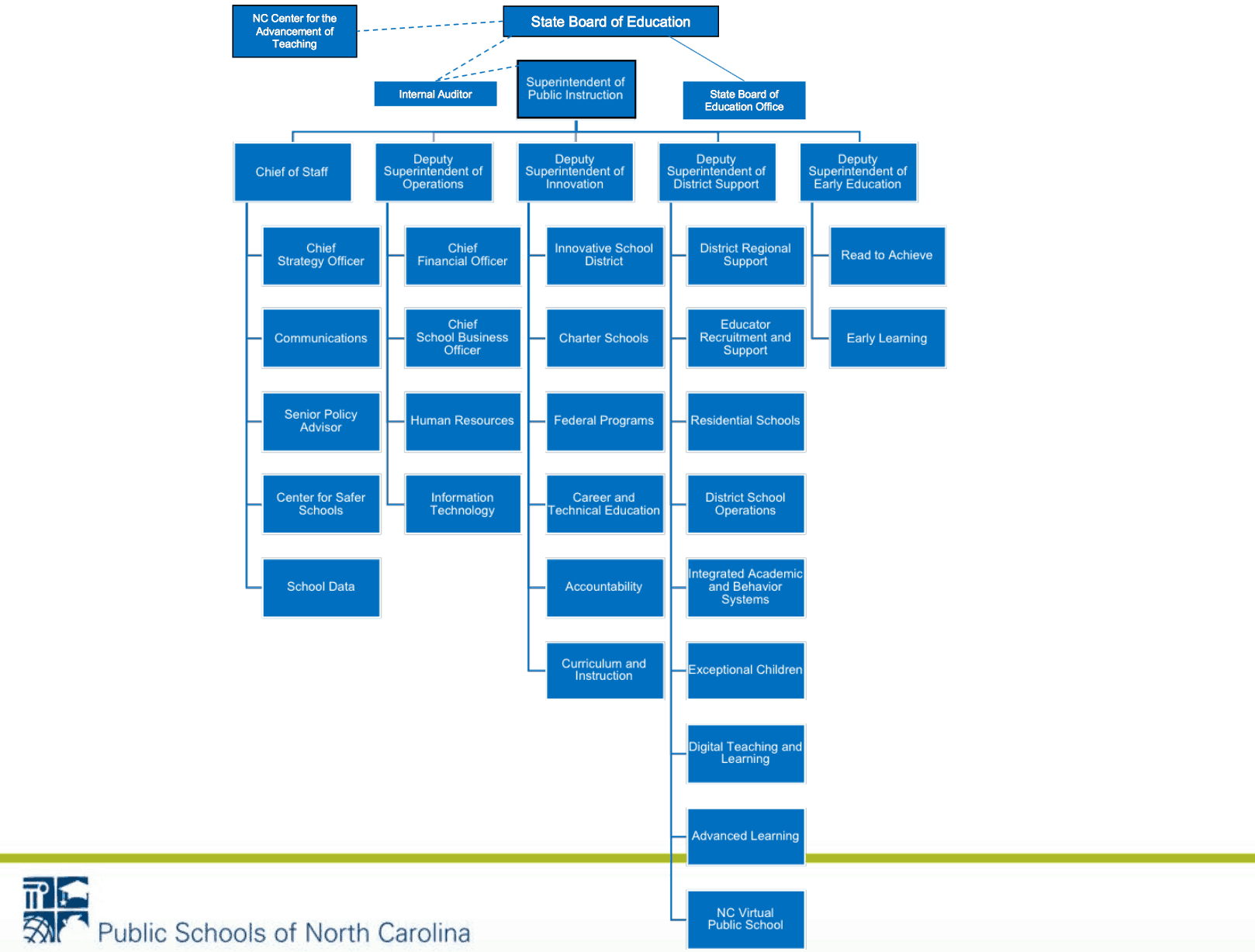

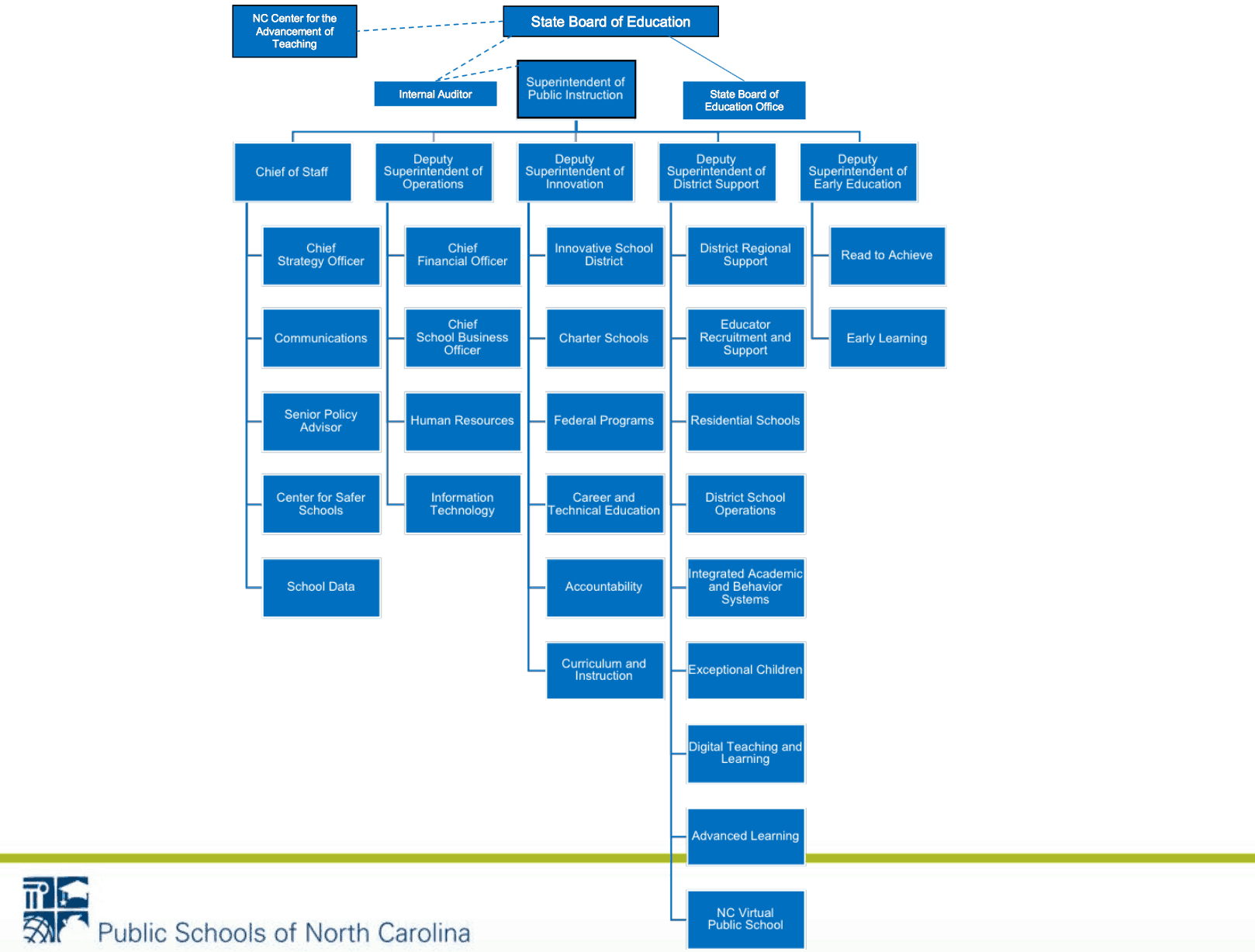

On the first day of the State Board meeting Wednesday, Johnson went through his newly announced organizational chart for the department.

The new structure features four new deputy superintendent positions that report directly to Johnson and lead the bulk of the organization. New roles include deputy superintendent for innovation, which is being filled by Eric Hall, the current superintendent of the Innovative School District (ISD). Hall will continue serving as acting superintendent of the ISD until a replacement can be found. The chart above shows the complete structure of the organization and positions it contains.

Johnson has talked often about the need to eliminate silos at DPI, a message echoed in the recently conducted independent audit of the department. It’s a message Johnson returned to on Wednesday during his presentation.

“This org chart is one step in that direction,” he said. “But it’s just a step.”

He noted that he shared the organization chart with members of the State Board ahead of its release to solicit their feedback. He pointed out comments from Board member Wayne McDevitt in particular, saying that McDevitt told Johnson that a new organization chart alone will not eliminate the silos at DPI. Johnson said he agreed and he said that no matter where in the organizational chart a position lay, the person in that position needed to know that they could reach out to others in DPI.

Johnson also discussed the Chief of Staff role, which he said he has received questions about. He said that role is essentially a project manager position, and the goal of the person in that position is to see where people are having trouble and break down any roadblocks in their way.

Johnson talked about the “limbo” that he has been in since starting the job. That limbo stems from the lawsuit between the State Board and Johnson over powers transferred to the Superintendent from the Board in legislation passed during a special session in December 2016. Johnson said that “limbo” created separation between education leaders and DPI.

“For the last year and a half, it has been the State Board, the office of the state Superintendent and DPI,” he said.

He also mentioned money he got from the General Assembly that allowed him to hire positions that reported only to him. He had taken to calling the people filling those positions his “team,” he said. But now that he has ultimate authority over DPI, those positions are being folded into the department. He had a message for staffers of DPI at Wednesday’s meeting.

“You are my team. This is the team. We’re moving forward,” he said.

He also struck a more conciliatory tone with the State Board, noting that they were put at the top of the organizational chart because they make the “rules and regulations for our public schools,” and they are in charge of general supervision of the state’s public schools.

Johnson mentioned some of his priorities going forward during his talk Wednesday. One of them, testing, was a subject he mentioned at numerous points during Wednesday’s meeting. He said the state needs to figure out what tests everybody is taking, which ones are worthwhile, and which ones can be eliminated.

“That’s one of my top priorities,” he said.“Even if we have good tests, what is the cumulative affect of all those tests on teachers and students?”

Johnson also talked about holding charter schools accountable. Previously, the office of charter schools reported to the State Board, but now they are Johnson’s responsibility and fit into the organizational chart under the deputy superintendent of innovation. Johnson said he is committed to making sure that charter schools that aren’t up to snuff aren’t allowed to continue operating.

Are elementary teachers falling behind in their math skills?

Last month, the State Board approved a policy that would let teachers who had not passed their licensure exams within the time permitted to continue teaching for another year. In that time, they would have to pass the exam.

Part of the need for this has to do with teachers who are not passing the math test required for licensure. Thomas Tomberlin, director of District Human Resources at DPI, presented on the subject and left the Board with the takeaway that DPI needs better information before it can figure out what’s going on.

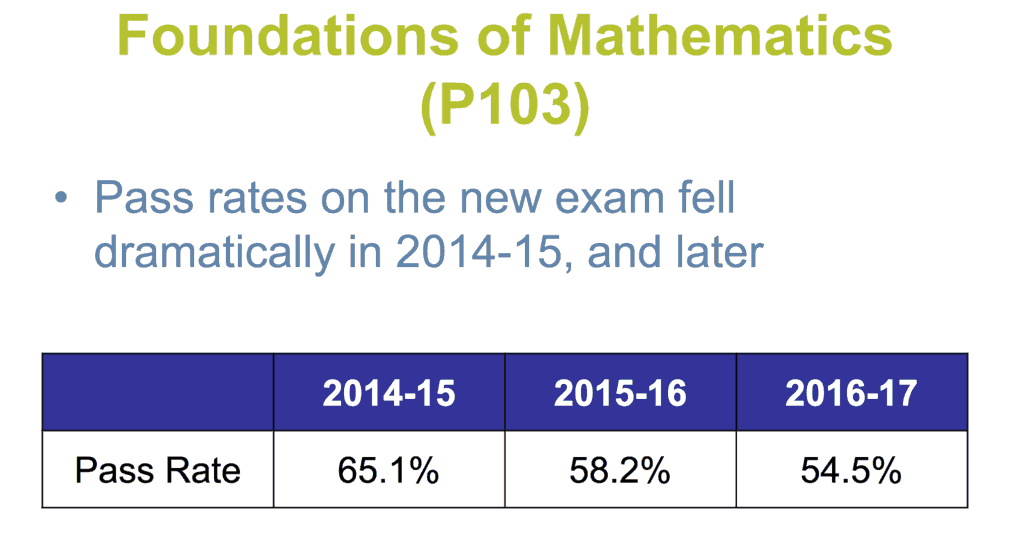

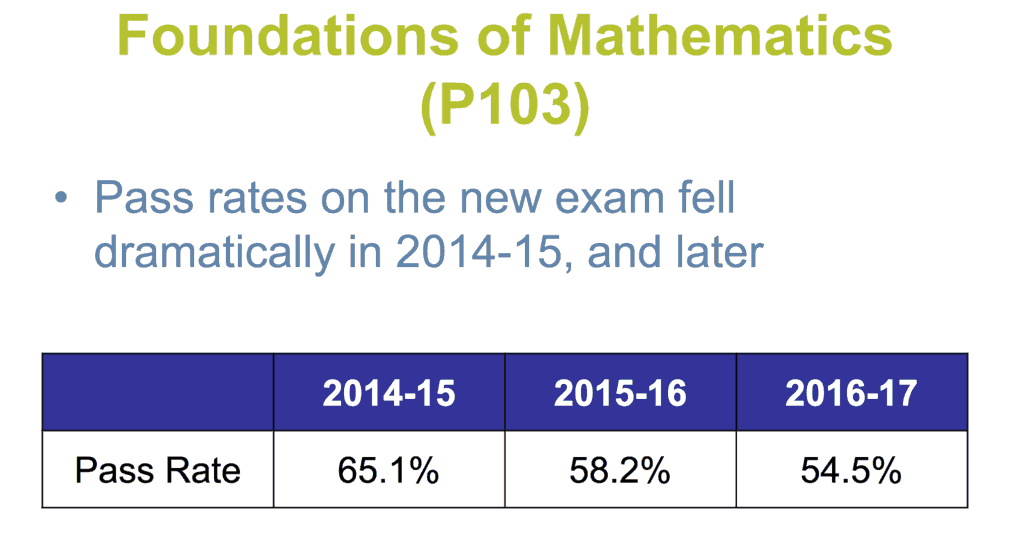

New tests from Pearson Publishing Company were adopted by the state after the 2013-14 school year, and pass rates plummeted for teachers. But the situation is more complicated than the numbers suggest.

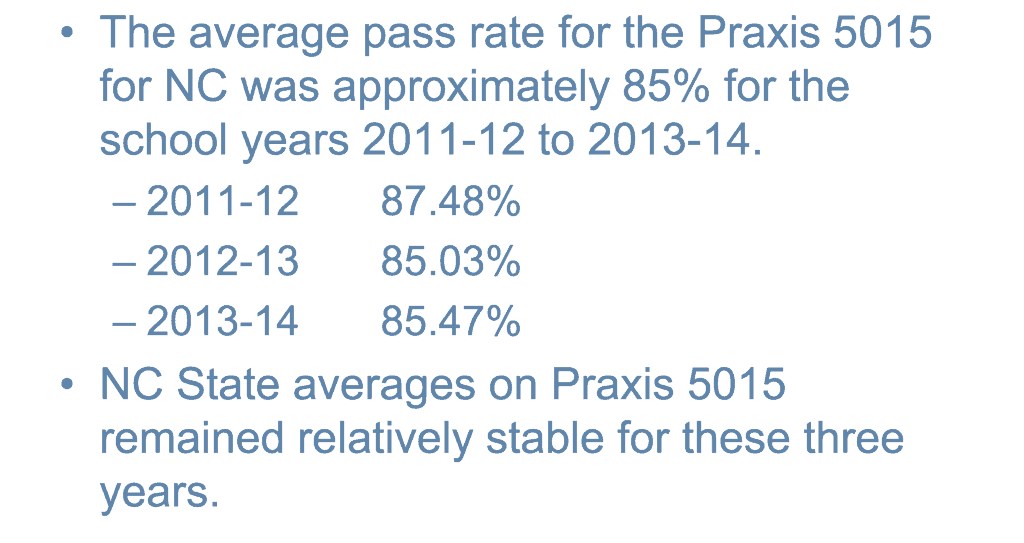

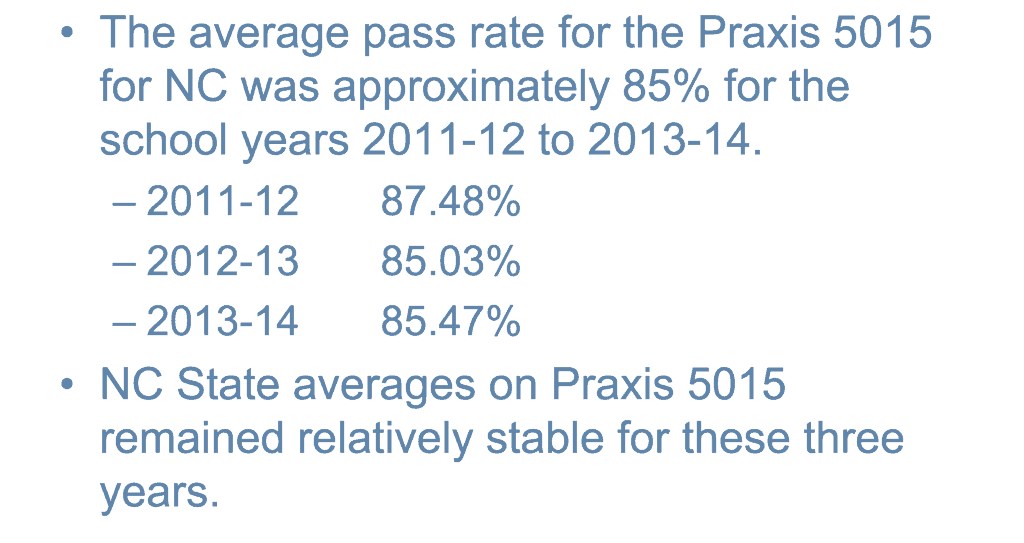

Prior to the 2013-14 school year, teachers had to pass an exam called the Praxis. If they didn’t pass, they couldn’t be hired. Pass rates were pretty good.

After the 2013-14 school year, the state adopted Pearson tests that measured separate subject areas such as reading and math. The rates fell.

But Tomberlin said that it’s impossible to compare the rates on the old tests to the new tests because the situation is completely different. Before, teachers had to pass the Praxis before they could start teaching. The pass rates collected by the state don’t reflect how many times teachers had to take the test before they passed.

Under the new tests, teachers have two years to complete the tests. Tomberlin said that in 2014-15, 23.4 percent of those who failed the exam did not try again the same year. That rose to 30.2 percent the next year and 36.4 percent in 2016-17.

“A lot of them just kept waiting until next year,” Tomberlin said. “Now, we have a great number of teachers who have not passed this test and are now seeking relief under this policy.”

It’s possible that allowing teachers to delay passing the test has contributed to larger failure rates due to teachers deciding not to retake and pass the test the same year, Tomberlin explained.

But the bigger problem, Tomberlin said, is a lack of information. DPI did not previously have the ability to “accurately track” which teacher candidates had actually taken a licensure exam. He also said it was impossible to tell how many teacher licenses would expire because of teachers not passing the test. His message to the Board was that better information is necessary in order to determine what problems, if any, there are.

“The current pass rates that you’re seeing can in no way be compared to the prior pass rates,” he said. “It is a false equivalency.”

Part of the policy approved by the State Board last month requires that all licensure exams need to be reported to DPI. That will help. A subcommittee of The Professional Educator Preparation and Standards Commission is also looking at the math test to see if it aligns with the state’s K-8 curriculum and to explore other testing options.

With better information, Tomberlin said that the state can also getter a better handle on if there is a relationship between passing the test and being an effective educator.

Johnson chimed in, saying that examining how the state does licensing is a priority for him.

“One of the first things we’re going to look at is the licensing department itself,” he said, adding that the department will ask tough questions such as: “Are [the tests] proving that someone is going to be a good teacher?”

School psychologist reciprocity

During the short session, legislation was proposed that would have allowed people with a Nationally Certified School Psychologist (NCSP) credential to practice as a school psychologist. After controversial language related to health insurance was added to the bill, it stalled in the legislature. But that doesn’t mean the idea is dead.

On Wednesday, the State Board approved a request to the Professional Educator Preparation and Standards Commission (PEPSC) to come up with a plan for a reciprocity agreement for school psychologists. According to Cecilia Holden, legislative director at DPI, a reciprocity agreement does not need legislation to happen.

Read more about the need for school psychologists and the failed legislation that would have addressed the issue here.

Renewal School District

The State Board also voted to approve the Rowan-Salisbury School District to become the state’s first renewal school district.

During the short session, the General Assembly passed legislation that would allow the school district in the state with the highest percentage of restart schools to become a “renewal school district,” essentially granting charter-like flexibility to all the schools in its district.

Restart schools are continually low-performing schools that apply for restart status with the state. The status allows them to operate their school exempt from some of the rules most traditional schools follow, much like charter schools. It allows them to do things like change their school calendars and use money in ways not designated by the state.

With 16 restart schools approved, Rowan-Salisbury has the largest proportion of restart schools in the state. Read more about the origins of the renewal school district here.