The General Assembly asked its Program Evaluation Division to look at what makes predominantly disadvantaged districts succeed academically. The division studied 12 districts both inside and outside of North Carolina that meet that criterion, which the report says is a rare combination, and looked at national data sets to find nationwide trends. The report’s key takeaway? Investment in early childhood learning.

The report, titled “North Carolina Should Focus on Early Childhood Learning in Order to Raise Achievement in Predominantly Disadvantaged School Districts,” was released today and recommends that early childhood learning be baked into the improvement plans required by the state from low-performing districts. It also recommends that when the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) conducts comprehensive needs assessments of low-performing districts with at least one low-performing school that includes grades K-3, part of that assessment include early childhood learning.

A draft bill that has not yet been introduced includes the above recommendations and can be found here.

At its core, the division’s project focused on three research questions:

- “What are the characteristics of school districts that have high percentages of economically disadvantaged students yet demonstrate high academic performance?

- What policies or practices are high-achieving disadvantaged districts implementing that may contribute to student performance?

- What policies or practices could North Carolina implement in order to improve performance in districts with high percentages of economically disadvantaged students?”

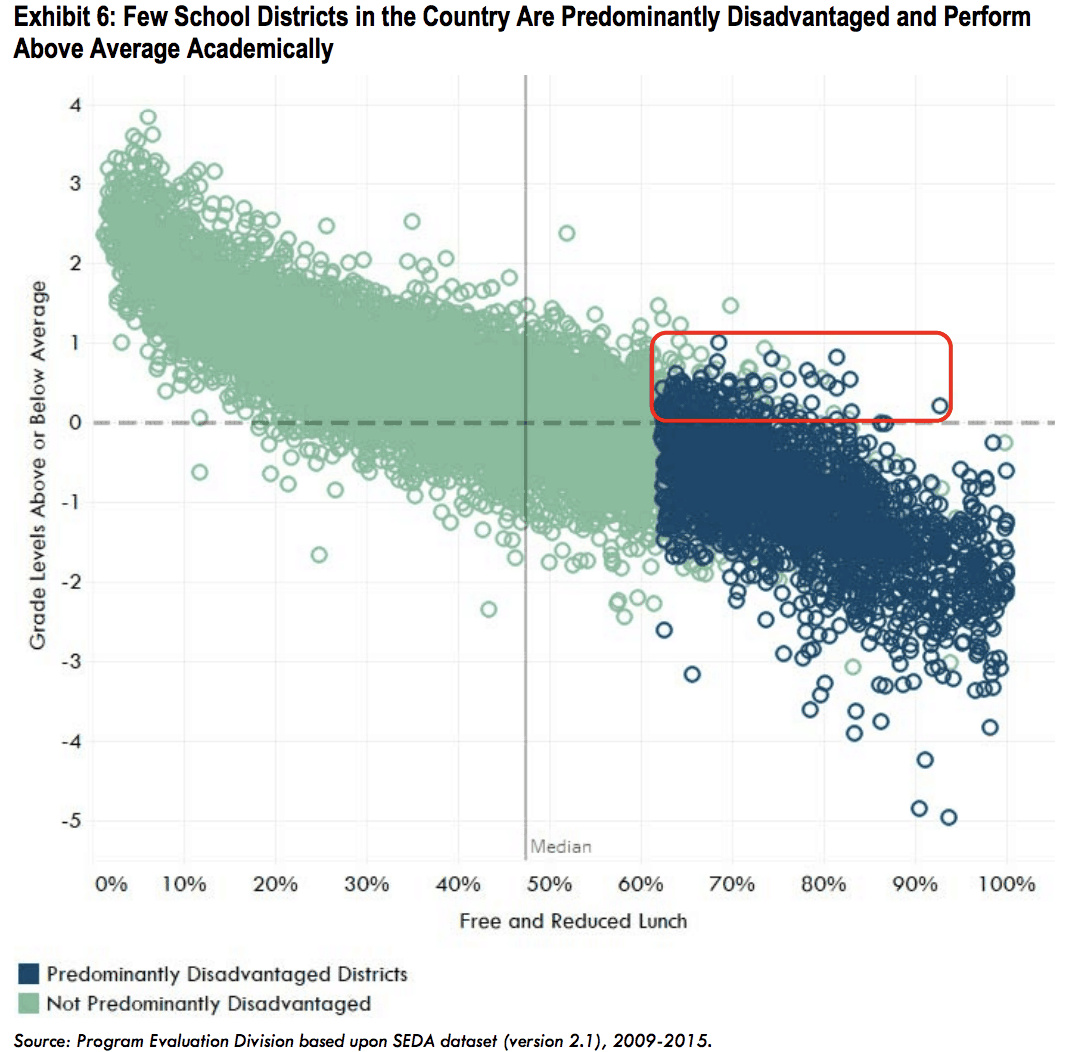

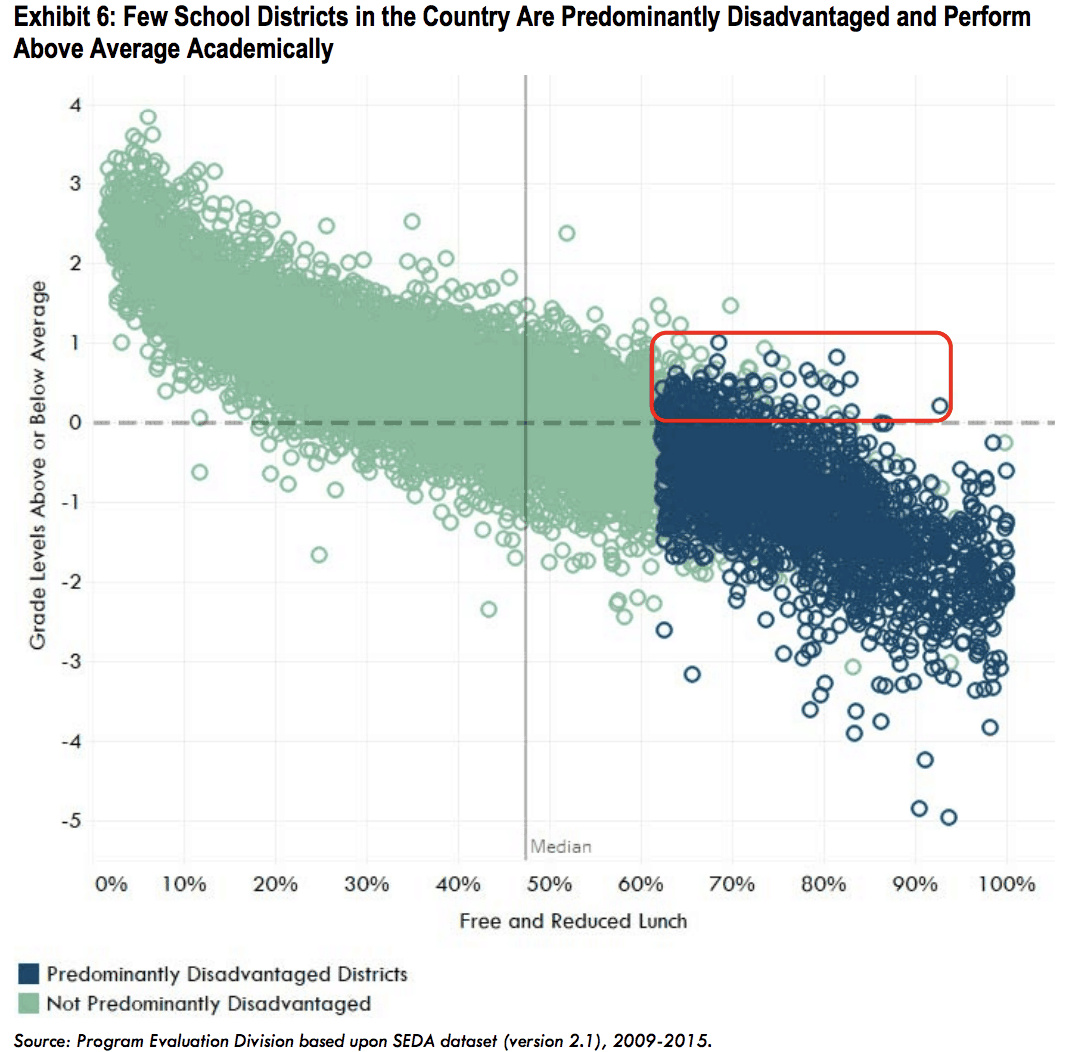

The project measured achievement by “the amount that average test scores fall above or below grade level within a given school district” and defined disadvantaged based on two factors: the percentage of students eligible for free- or reduced-price lunch and the district’s socio-economic status, which considered median income, percentage of adults ages 25 and older with a bachelor’s degree or higher, the poverty rate for households with children ages 5-17, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program receipt rate, the single mother household rate, and the employment rate for adults ages 25-64. The national data set the division used was from the Stanford Education Data Archive (SEDA), which puts results from varying third through eighth grade math and reading state tests on a common scale and provides other information on district-level educational outcomes across the country.

The report’s first finding centers around the fact that it is rare to find high-achieving disadvantaged school districts. The report found that only 5% of districts in the national data set were both predominantly disadvantaged and performing at or above grade-level.

In North Carolina, the report classified 39% of school districts — or 45 of 115 — as predominantly disadvantaged. Nationally, 18% of states’ districts received that designation. Sixteen percent of predominantly disadvantaged school districts in the state — or seven of 45 — performed at grade level or above. That’s a little higher than the national 5% of high-performing predominantly disadvantaged school districts.

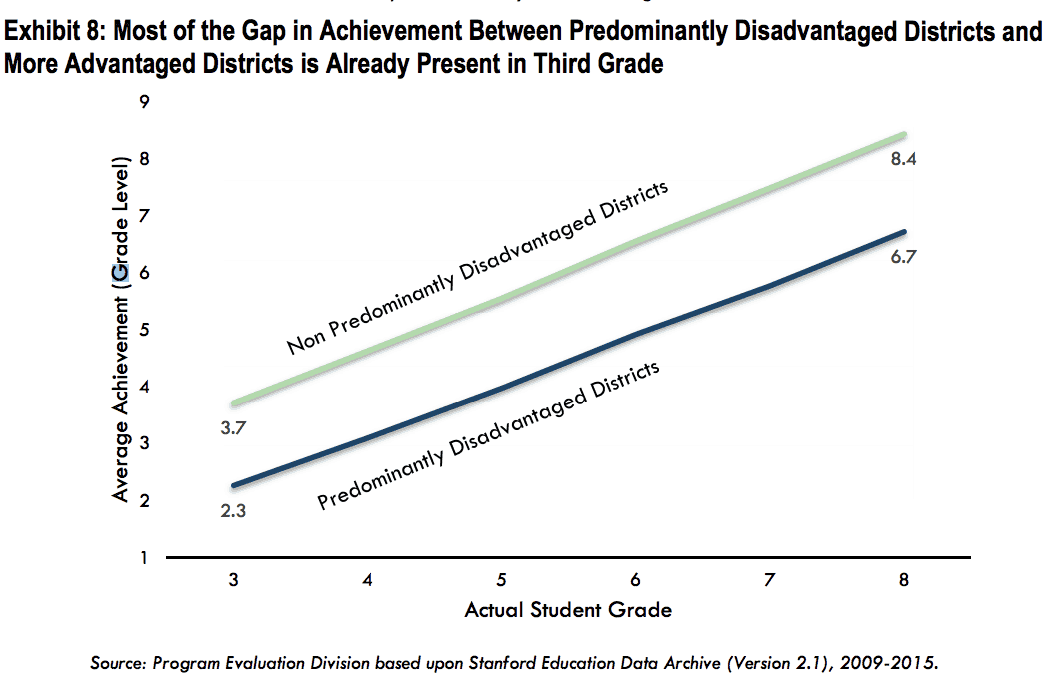

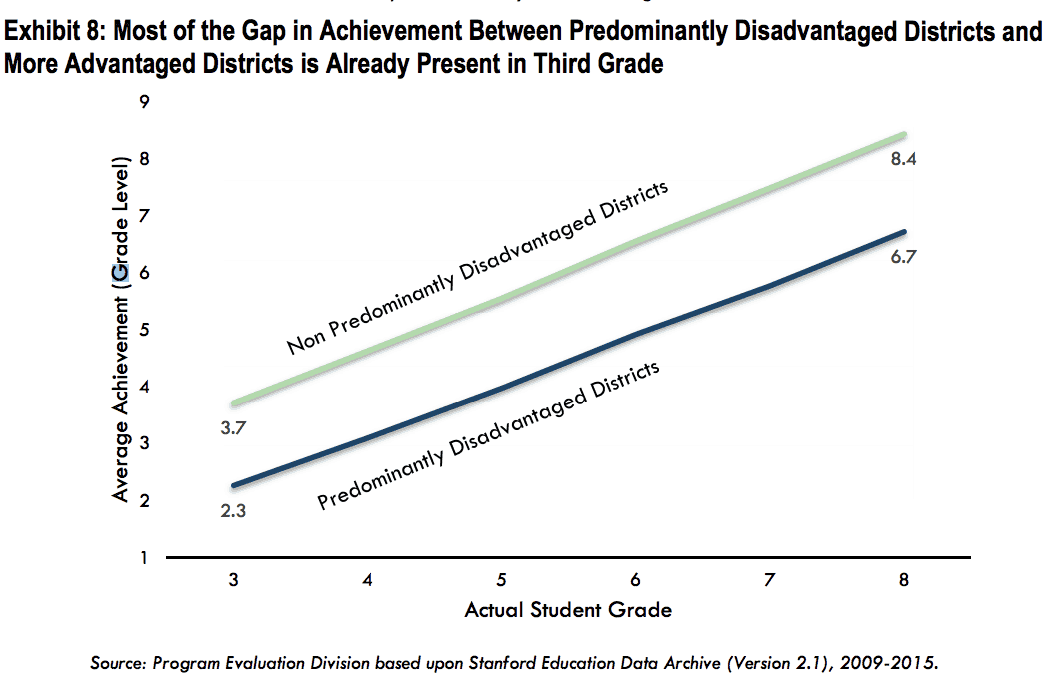

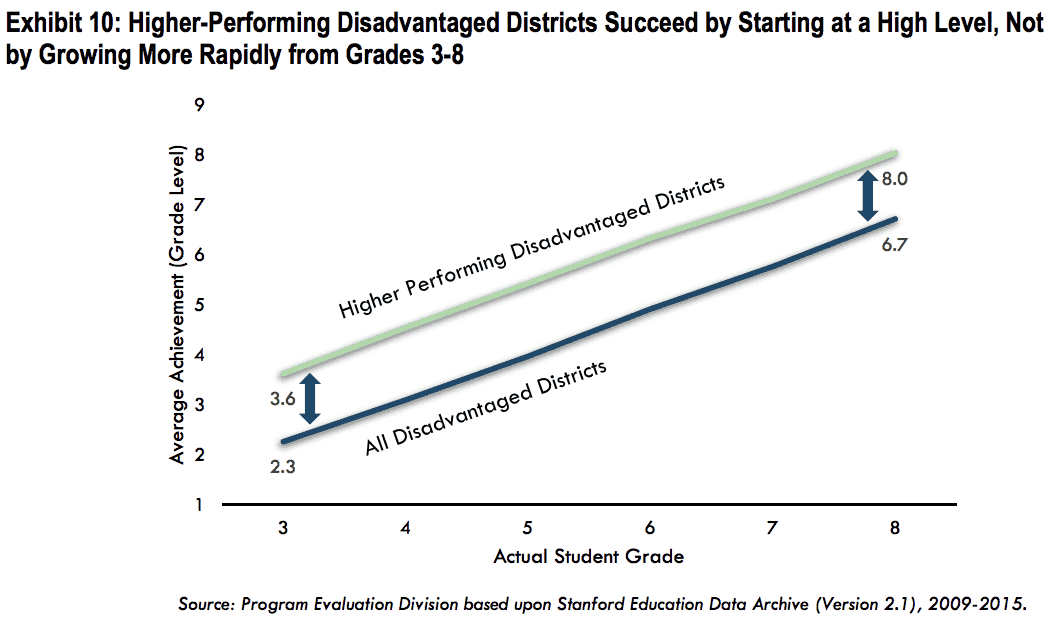

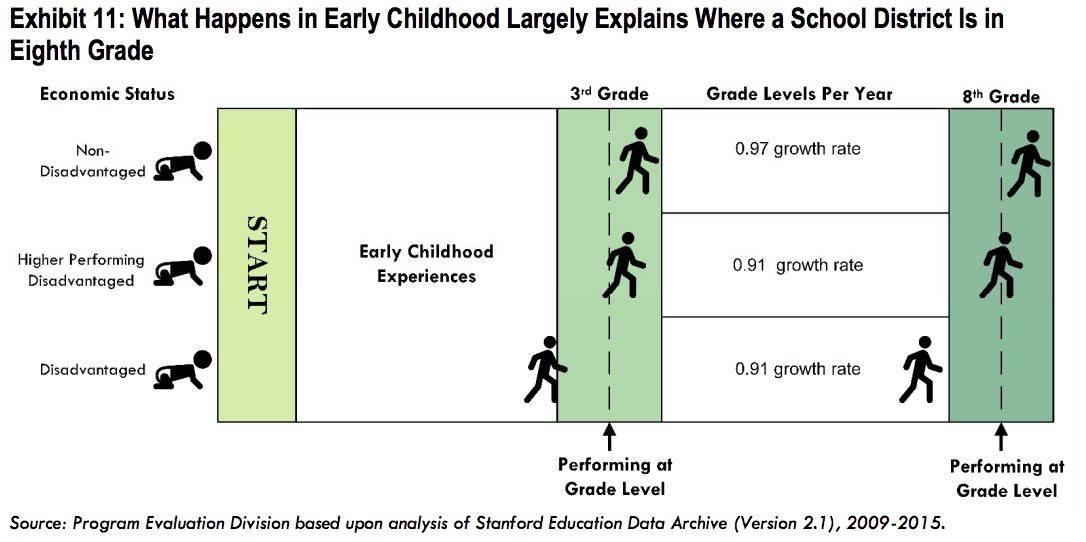

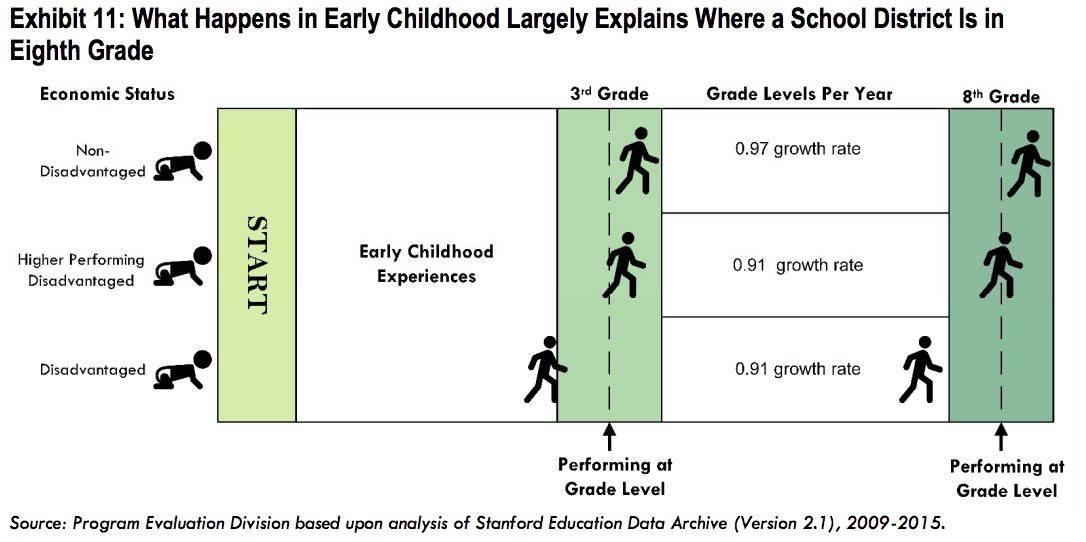

The report also found that most of the academic achievement gap between predominantly disadvantaged schools and those who are more advantaged exists by third grade. That gap, the report found, does not widen significantly between third and eighth grade. This finding points to the experiences before third grade as the most important in eliminating that gap.

“Because third grade is the first year for which data is available in the SEDA dataset, performance in third grade represents a cumulative measure of all educational opportunity prior to and including this grade level. The gap witnessed in third grade highlights the importance of early education in efforts to improve the performance of predominantly disadvantaged districts.”

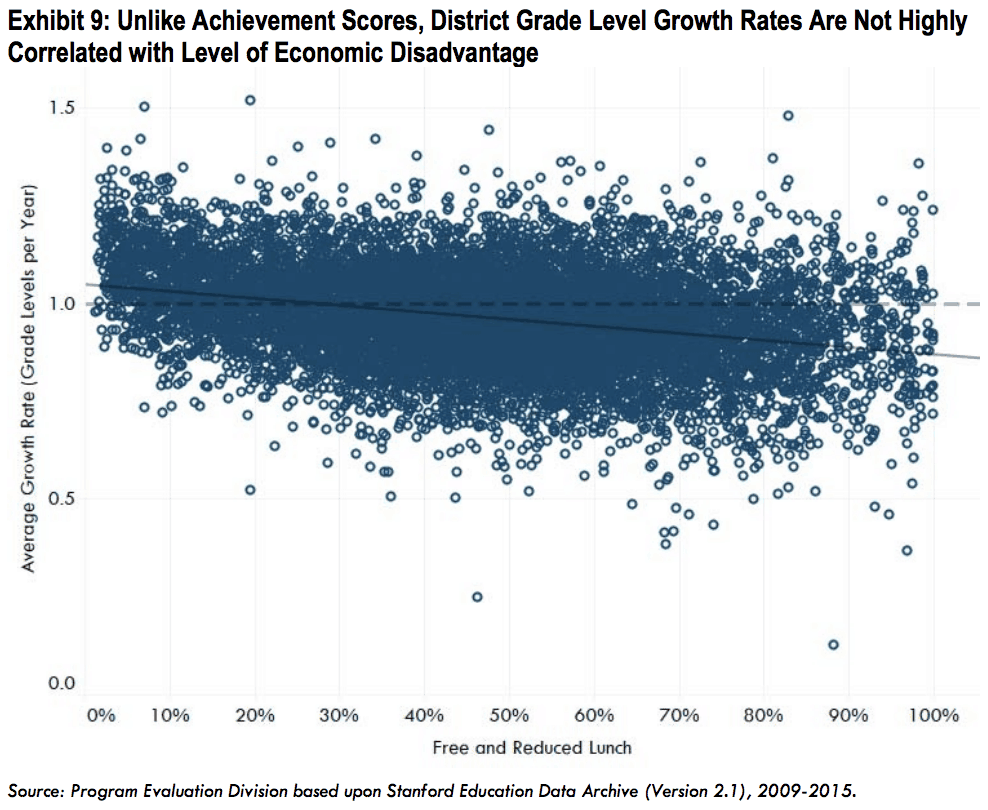

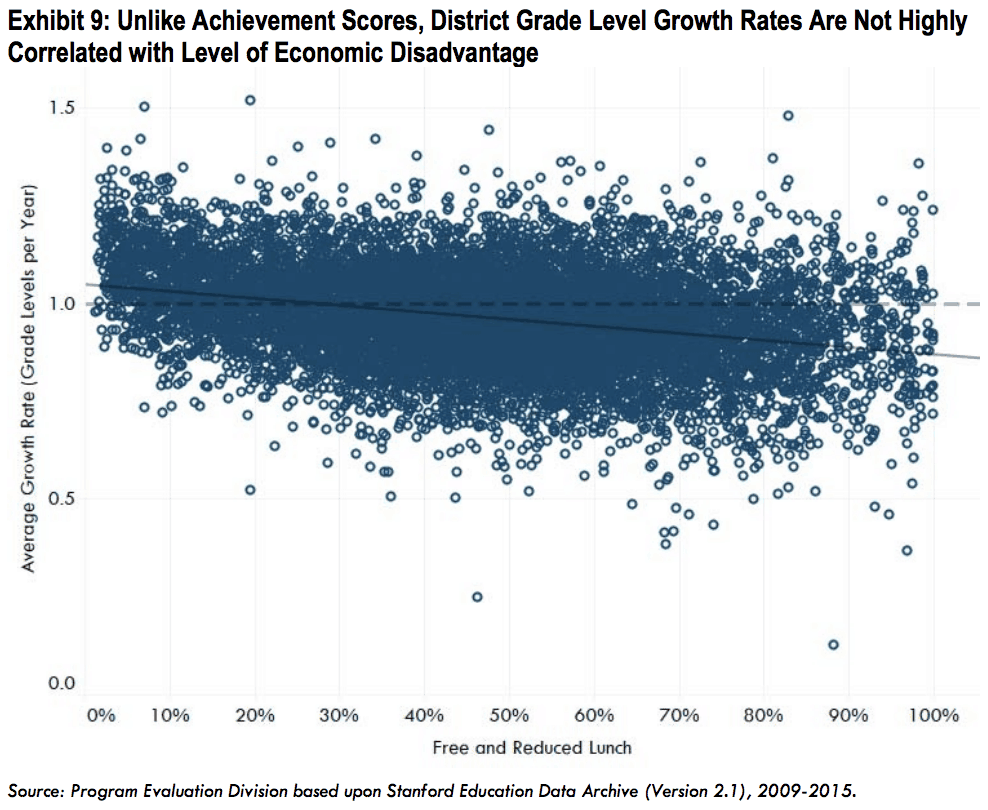

The report highlights the fact that growth in grades 3-8 averages about one year of growth per grade level, and that growth is not correlated with economic disadvantage in the same way that achievement is.

“This weak correlation provides further evidence that much of the difference in achievement between disadvantaged districts and more advantaged districts owes to disadvantaged students being behind by third grade and is less the result of a lack of growth from third through eighth grade.”

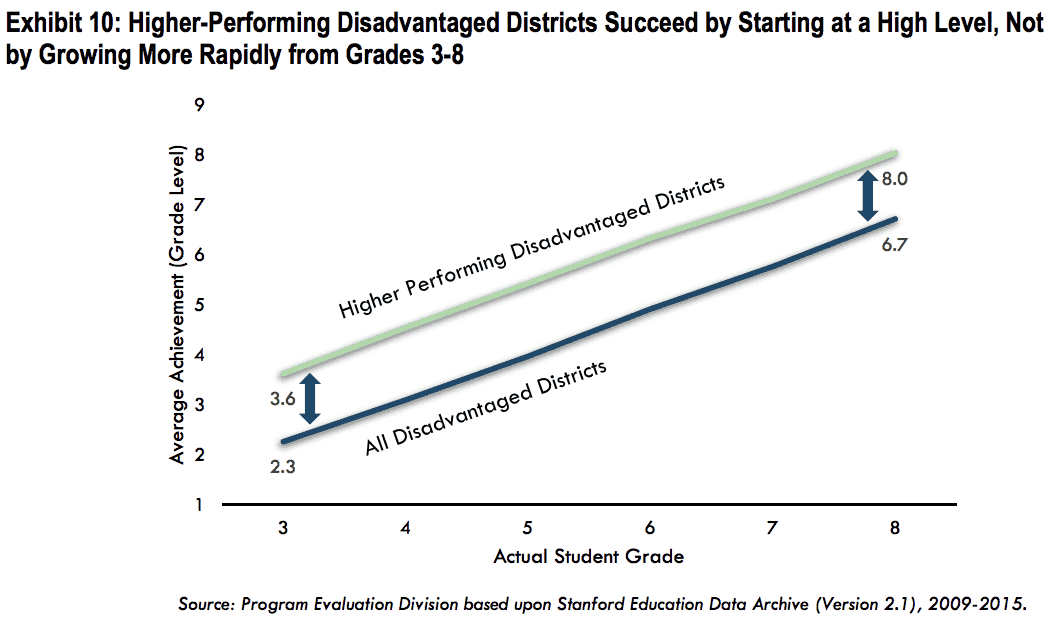

The report similarly found that the gap between high-performing disadvantaged school districts and disadvantaged school districts who were not high-performing exists by third grade.

Division researchers note this is not to discredit the importance of education after third grade, but to highlight that if a strong start is not there, it gets harder and harder for a district to catch up in later grades.

“This observation about the importance of achievement by the end of third grade is not meant to suggest that what happens from third to eighth grade and afterwards is unimportant. Gains achieved by third grade can be lost in succeeding years, a process often described as “fade-out.” However, because gains in achievement take place through a cumulative process wherein mastery of skills or concepts continue to build upon one another, it is much more difficult for school districts to reach a high achievement level in later grades if school districts are performing poorly in earlier grades. For a district in which third graders perform one grade level below average, a growth rate of 1.2 grade levels per year would be required in order for the district to be achieving at grade level by eighth grade.”

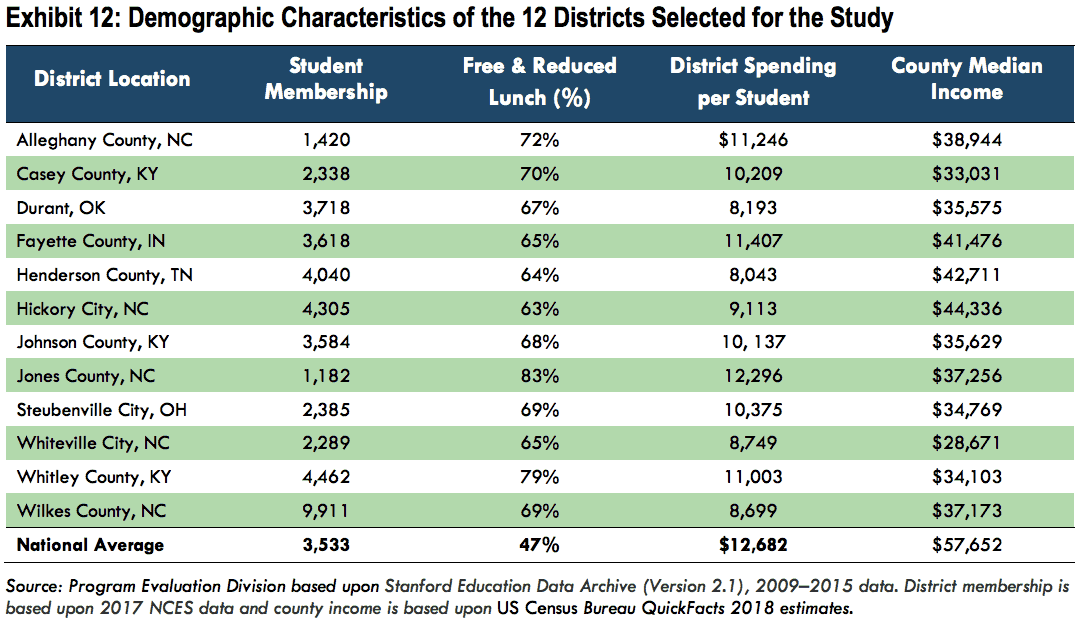

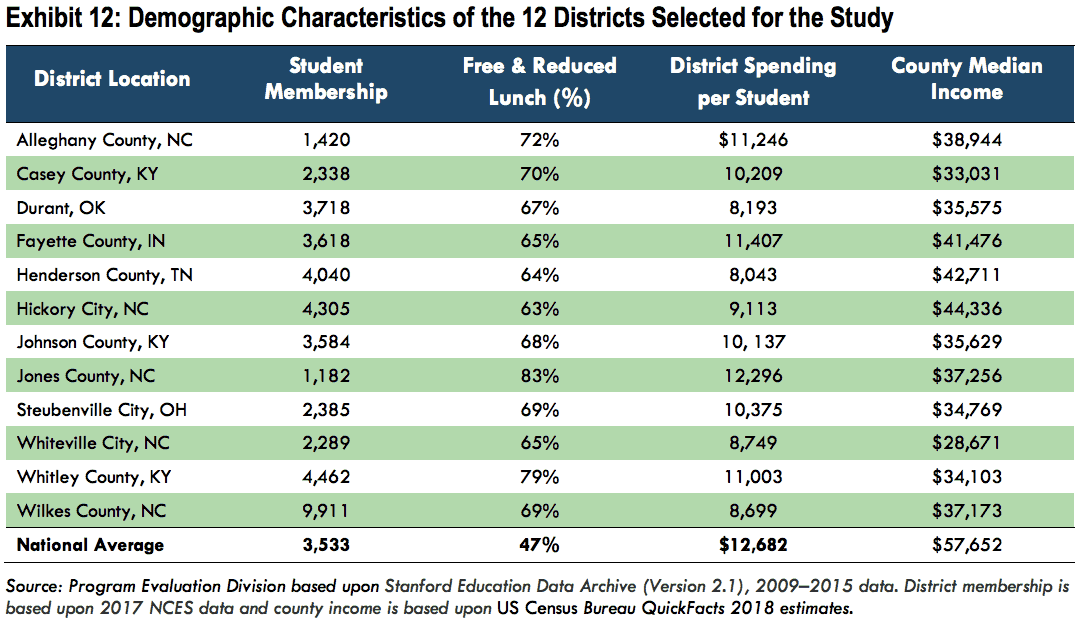

The report found a set of common characteristics among high-performing predominantly disadvantaged school districts based on interviews with the 12 school districts they selected. Information on each district, five of which are in North Carolina, can be found below.

From the case studies of these 12 districts, the division provided six commonalities that led to these predominantly disadvantaged districts performing at or above grade level.

- “Focusing on early education”

The report found “the case study districts all valued early education and pursued efforts to support and expand it.” In four of the five North Carolina school districts, the rates of participation in NC Pre-K, the state’s preschool for at-risk 4-year-olds, are higher than 75% of eligible children — and fall in the state’s top quartile of participation. The other out-of-state districts provide varying state preschool programs, mostly for 4-year-olds. In Whitley County Schools in Kentucky, the district works with community partners to target children before preschool with programs at home that include literacy and other supports.The report also mentions the importance of supporting children during the transition from preschool to kindergarten, like communication between preschool and kindergarten teachers, student visits to kindergarten classrooms before school starts, and families giving information to kindergarten teachers.

- “Increasing or maximizing student learning time”

The successful schools in the case study all used varying strategies to increase or maximize student learning time. Some of these efforts targeted students that were behind with extra support and instruction during the school day. Others extended the actual school day before and after through re-purposed funds or grant money.The report mentions that researchers have found varying results when studying if increased instructional time actually improves student outcomes.

- “Seeking additional outside resources”

The report found schools in the study were always looking for opportunities, from public or private sources, to better support their students during and after school hours — from helping teachers integrate technology into their teaching practice to providing before and after school academic and extracurricular activities for students. - “Attracting, developing, and retaining high-quality teachers”

The report highlights the importance of recruiting and retaining high-quality teachers, especially for disadvantaged students. High turnover and the instability it creates in the classroom, the report said, negatively affect student outcomes. The report outlines three conditions that research links to the likelihood that teachers will stay at a particular school, which “are larger factors in causing teachers to leave than the demographics of their students” — administrative support, collegial support, and positive school culture.The report emphasized the need for strong principals with “managerial, instructional, and interpersonal skills” in the retention of teachers. The report also said districts that allowed superintendents, principals, and teachers to lead within their own spheres were more successful. When it comes to collegial support, the report said both formal and informal opportunities for instructional feedback, relationship building, and mentoring are important in teachers’ needs. The report also said the norms, beliefs, and values held by the people at the school — which add up to its culture — are strong predictors of teacher satisfaction and likelihood to stay.

“A common assumption is that teacher turnover occurs because teachers prefer to work with higher-income students with fewer behavioral or social-emotional challenges, but research indicates that teachers more frequently tend to leave a school due to organizational conditions such as a lack of strong leadership or school-wide norms around discipline.”

- “Using data and coaching to improve instruction”

Successful schools, the report said, use data collection and analysis to adjust instruction and programming to meet students’ needs. Support for teachers, especially beginning ones, is important to improve teachers’ skills. Several of the districts interviewed by the division, the report said, use instructional coaches to provide feedback and additional training around certain subject or content areas. - “Promoting a local school board focus on policy and academic achievement”

The report suggests that school boards that give autonomy to superintendents and focus on overall student achievement and policy, rather than day-to-day administrative decisions like personnel, are more effective.

You can find the entire report below.