|

|

When Hickory Public Schools landed on a warning list for identifying a significantly disproportionate number of Black students as having mild intellectual disabilities in 2017, it took a look at its practices.

At that time, the district was more than six times as likely to place a Black student in Exceptional Children (EC) services for mild intellectual disability (mild ID) than a student of any other race. Upon closer examination, the district realized the disparity extended to many other areas, too.

“When we look at our EOG scores, when we look at our discipline data, when we look at everything, the data just kept coming back that our Black students were disciplined more, our Black students were suspended more, our Black students were removed more, our Black students did not have the EOG scores compared to other [groups],” said Tammy Beach, the EC director for the district.

That doesn’t make Hickory Public Schools much different from many other districts in the state. Public schools in North Carolina, on average, are more likely to identify Black and Brown kids as intellectually disabled or having emotional disorders. And for years, the Department of Public Instruction (DPI)’s Exceptional Children Division has searched for solutions to that.

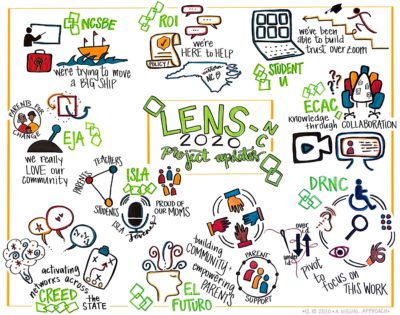

One that it’s trying now is through the ARISE NC program, a collaboration between the State Board of Education and DPI. Through membership in Learning for Equity: A Network of Solutions (LENS), the State Board and DPI received funding and advice for training and coaching on such things as using data efficiently and checking implicit bias. And they’re helping districts, like Hickory, do better.

“We knew that there were some data tools that we could develop, and we knew that there were some significant, probably unconscious biases that were leading to some of these [placements],” said Matt Hoskins, assistant director of the EC Division. “That’s what led to the root cause analysis and the determination of where we wanted the goals to be, and the type of work that we wanted to do.”

Partnering to address racial disparities

The State Board passed an equity resolution last year, and this year the EC Division revised its strategic plan. Aligned with the State Board’s strategic plan, it is called Equity in Excellence. The shared interest in equity and the timing of the LENS initiative prompted the partnership, a rare one between the Board and a specific division within DPI.

“When you look at disproportionality across the state, we can have some major wins in this area by focusing and attacking this using an equity lens,” said Deanna Townsend-Smith, the State Board’s director of operations and policy. “And [EC Division Director] Sherry [Thomas] and her team are phenomenal at meeting and doing this work.”

Dreama McCoy, a section chief in the EC Division, and Danielle Allen, who works on research, policy, and strategy support for the State Board, led efforts to train districts on policy, data, and using a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS).

Much of the work, and some of the harder work, involved examining implicit bias.

“We are requesting them to think about equity at every meeting, thinking about equity in everything they do, because it’s those unconscious biases that really are issues that lead to disproportionality,” McCoy said. “Part of it is the awareness level and recognizing that there might be some unconscious biases. That’s very difficult because you think you’re doing what’s right, not even being aware that some of the conversations and things you may be having or indicating or sharing really may be leading to some type of bias.”

An unconscious bias is one we are unaware of and happens outside our control — triggered by our brain making quick assessments of people and situations based on our backgrounds, cultural environments and personal experiences. The concept of implicit bias is similar, but it takes into account that the knowledge to become aware of it is out there, and we are accountable for learning it. In one school district that joined ARISE NC, teachers confronted their unconscious biases and continue to work on implicit bias.

How ARISE worked in one district

Federal law mandates that states track disproportionality in districts, and any district that is three times more likely to place a student from one race in a particular category of disability is put on a warning list. That was Hickory Public Schools in 2017.

If a district on the warning list does not significantly reduce that rate in three years, it lands on a “significant disproportionality” list — and must allocate certain funding to address the issue.

“It became a real focus for us as to why were our Black kids six times more likely to end up with EC eligibility in the area of mild ID,” Beach said.

The district re-evaluated every student who had an individual education plan (IEP), examined its use of MTSS, and checked whether EC Division policy was being followed for identification and placement of students in EC services.

The district had noticed data disparities for its Black students in several areas — not just placement for ID services. So, even before joining the ARISE cohort this past year, the district began working on implicit bias.

When it re-evaluated placement decisions, the district found that teachers were relying heavily on one metric — IQ score. However, both law and policy say several factors should be considered.

Beach said teachers actually were trying to help these Black students, believing they needed extra support and trying to get it for them through ID placement. But that placement can have unintended consequences.

“There can be harms, particularly for students who might be misidentified,” said Meghan Whittaker, policy and advocacy director for the National Center for Learning Disabilities (NCLD). “Very often students with disabilities are seen as less intelligent or less capable. Expectations can be lowered for students in special education. Oftentimes, we see the rigor of classes might decrease for those students, and there’s also a stigma that’s associated with it.”

Hickory Public Schools came off the warning list this year, as it reduced its disproportionality ratio from more than six times to less than three times. Beach credits the progress to participation in ARISE, which helped the system understand what data to use and how to pull that data — as well as the importance of implicit bias training.

Beach said several educators in the district received implicit bias training from DPI, and district leaders received training from a professor at UNC Charlotte.

“I don’t think anybody was intentionally trying to do anything negative towards our students,” Beach said. “But were our students being given a fair shake? It’s very uncomfortable; it can be a very uncomfortable conversation. If you’re being honest, it is uncomfortable. … But you have to have them.”

Why the conversation — and training — is needed

In 2019, four researchers set out to settle the debate over why Black and Brown kids are disproportionately identified for emotional and intellectual disabilities. One theory was that they are more likely to experience poverty, and poverty has effects that correlate with these disabilities. The other theory: It’s unconscious or implicit bias.

The study, published in the Harvard Education Review, found that racial bias was a factor independent of income.

“I think you can’t talk about disproportionality without talking about racism in our schools,” said Reighlah Collins, an attorney on the education team at Disability Rights NC (DRNC).

Collins said the impact of placing Black and Brown kids in EC services they don’t need — like those for emotional and intellectual disabilities — can have consequences even beyond those Whittaker outlined dealing with lower expectations and rigorous coursework.

These students, she said, could be more likely to end up in the criminal justice system when real, underlying issues such as specific learning disabilities, ADHD, or trauma go unaddressed.

As part of their work in LENS, DRNC conducted a national survey of states and significant disproportionality. North Carolina is on par with the country, it found, but that isn’t a distinction worth celebrating.

DRNC is now developing training materials about all aspects of special education, including disproportionality, geared toward parents, advocates, and — importantly — juvenile court counselors and judges.

“I want people who are adjacent to the school to understand what the school’s affirmative obligations are, particularly juvenile court judges and juvenile court counselors,” said Ginny Fogg, the lead attorney for DRNC’s education team. “Because I want them to then feel empowered to put stuff back on the school to be like, well, I see that you’ve sent me this kid, did you ever do a [functional behavioral assessment] or a [behavior intervention plan] for this kid? I want them to have that level of knowledge about the school’s obligations.”