Walking the halls of Clayton High School on a Saturday in January was a young man in a janitor’s uniform, pushing a trashcan or sweeping the floor, mostly keeping to himself. His name was Stephen McKinney. He was not a janitor.

McKinney interacted with dozens of teachers looking to become principals. He is a research graduate assistant for North Carolina State University’s Principal Preparation Candidate program. The candidates, interviewing and auditioning to spend two years in one of the program’s regional leadership academies, did not know McKinney’s impressions were being documented and judged on a “Serendipitous Encounters” rubric. He documented if and how candidates interacted with him.

The program looks for “candidates who show compassion, kindness, and professionalism to everyone they meet and not just the evaluators,” according to the rubric. Program Director Bonnie Fusarelli put it this way: “What we’re really looking for are some of these soft skills, because there’s a lot of skills that we can teach, but there’s a lot of basic ‘who you are’ that we really are trying to select for.”

Ahead of choosing their eighth cohort, Fusarelli said her team recently reassessed the goals of the program, asking what kind of leaders they want to create to administer schools. Then they split the traits into two categories: those that can be taught through coursework and training, and those that should already exist within individuals. The team looks for candidates who already possess attributes like empathy, compassion, relationship-building ability, and receptivity to feedback.

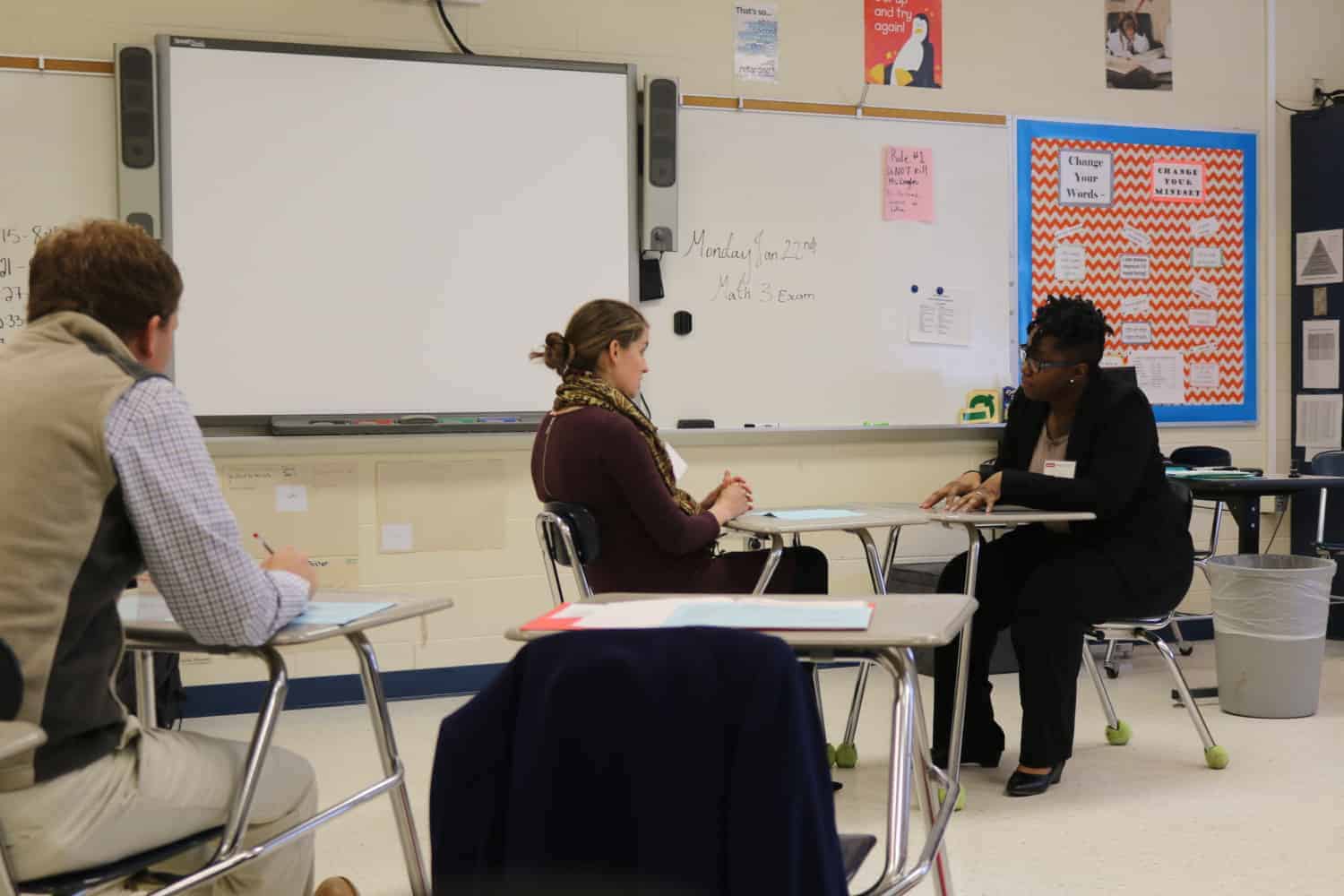

Throughout the assessment day, around 100 candidates went through rounds of role-playing scenarios, observed by evaluation teams made up of former program participants, education professors, Department of Public Instruction officials, educators, and administrators. Actors played teachers and students in situations principals commonly encounter.

For example, candidates had to meet with a faux-teacher whose colleagues had found was having issues with classroom management during peer observations. The actor was told to be stubborn, defensive, and elusive about the problem at hand.

In two different candidates, evaluators found strengths and weaknesses in their approaches. One candidate kept returning to ask the “teacher,” “How can I support you?” She kept the conversation with the actor moving forward, emphasizing the teacher’s need to set an expectation for her classroom and build relationships with her students. She let the “teacher” know of useful resources and set specific steps for evaluation moving forward. She provided suggestions to make sure students were not leaving the classroom unexpectedly — a specific observation the candidate knew about before the interaction. Evaluators were impressed with her attitude and the way she communicated appreciation for the “teacher” while still addressing the problem.

Another candidate struggled to get the “teacher” to talk about the issues in her classroom. The candidate got stuck asking, “What do you know about your students?” without meaningful replies from the teacher. She took pauses to take notes long after the “teacher” stopped talking, which evaluators noted would not translate well into an interaction with a teacher who is already frustrated and exhausted. The candidate suggested shadowing a master teacher to learn better management skills, which the evaluation team liked. Overall, the candidate did not show the soft skills Fusarelli wanted— the ability to effortlessly connect with others and work through tough problems together.

Michelle Young, executive director of the University Council for Educational Administration, said this rigorous assessment is part of what makes N.C. State’s leadership academies some of the best of their kind. The program is one of five that have been considered “exemplary” out of over 700 principal preparation programs across the country.

“The typical idea about leadership programs is that basically if you apply, that you get in,” Young said. “But that’s not what’s happening here at N.C. State. It’s obvious that they have a real specific kind of candidate they’re looking for. They carefully vet them and then that’s how they create their cohorts. I think that’s a huge takeaway.”

Young visited and participated in the evaluation process along with representatives from other university preparation programs. She said the variety of backgrounds on the evaluation teams is also essential in assessing candidates.

“You might have thought that the last candidate did perfectly well,” Young said. “And then, hearing the different perspectives around the room, you get a sense of, ‘Oh, yes, she definitely could have done better in that particular regard.’ We’re not looking for somebody who doesn’t show what they call, ‘heart’ or doesn’t really try to figure out what’s going on with the student beyond what it is that they say. I think that that’s really nice to have the different types of perspectives.”

In another scenario, participants had to address an upset student who had been skipping biology class. Candidates were provided information on the student’s difficult home life and otherwise high grades. After one candidate received feedback and tried confronting the student again, evaluators were unimpressed. The criticism did not focus on the candidate’s experience, but on the specifics of the conversation. They said it felt forced and had a condescending tone. The candidate, multiple evaluators agreed, had an idea of an “old school principal” that was ready to discipline instead of genuinely engaging the student.

Lisa Bass, an assistant professor of educational leadership at N.C. State, was one of the evaluators in the room. She looks to see if candidates search beneath the presented problem.

“Does the principal dig deeper into asking, ‘Is there anything that’s really keeping you from coming to class?'” Bass said. “Is there anything going on at home? Is there anything going on between the teacher (and the student)? So we look at the (candidate’s) ability to not have a deficit approach but to give the student the benefit of the doubt — to be caring, to be nurturing, but at the same time to get to the root of what the problem is and help the students take next logical steps to solve that problem.”

Bass said she sees principal preparation as a direct way to ensure high-quality education for students through retaining excellent teachers, especially in low-performing schools that struggle with retention.

“Teachers, of course they have the biggest impact on students,” Bass said. “But the administrators are the ones that make teachers feel comfortable enough to stay in that building.”

Without leadership programs like these, teachers typically do not reach administrative positions until late in their careers. This newer pathway to leadership is something that appeals to Sarita Shaw, a teacher at Olds Elementary in Raleigh who interviewed on assessment day. She said she feels like her experience in the classroom would inform her principalship.

“A lot of the changes that we want to see on the school level or ground-level are able to happen administratively,” Shaw said. “… The environment of the school and the achievement of the child can boil down to leadership. It’s that important. I think when I realized that personally, it inspired me to become a principal so that I could make some changes and provide that nurturing environment, provide that high expectation, for the sake of the kids.”

Recommended reading