Editor’s note: This article is part of EdNC’s playbook on Hurricane Helene. Other articles in the playbook are available here.

What happens in a region ravaged by a natural disaster, where communications are disabled and the power is cut off indefinitely? How do its residents react? How is help delivered to those in need?

Last year, the people of western North Carolina — and others across the state and the nation — organized in the face of disaster following Hurricane Helene. They acted on instinct and stood up aid distribution operations without training.

They saved each other.

Mebane Rash/EdNC

Mebane Rash/EdNC

In conjunction with state and federal government responses, communities found ways to address their needs and the needs of others. Aid was delivered on many fronts, from neighbors extending a hand to neighbors to grants from philanthropies.

What is mutual aid?

In real time and looking back, some people called what they were doing “mutual aid.” It’s a term that frequently surfaces after a disaster and that was in the spotlight in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina when groups organized first aid, food and water distribution, garbage cleanup, and other services in the absence of government response.

The definition of mutual aid varies depending on the context, but it is generally understood to be a community-driven, voluntary exchange of goods and services for mutual benefit. Often, mutual aid arises in response to natural disasters or prolonged systemic needs, especially among marginalized groups that might not receive adequate support from government institutions.

Mutual aid has paid emergency medical bills, run health clinics, and built housing. It has sustained communities and repaired them.

Philanthropic organizations and governments have used the term when investing both proactively and reactively in the infrastructure of communities, knowing that mutual aid networks are important day-to-day, and especially in crisis.

The state of North Carolina, for example, has a statewide mutual aid network that includes all 100 counties, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, and hundreds of municipalities as signatories.

“North Carolina’s Mutual Aid System is based on the premise that it makes sound economic and logistic sense to share some types of emergency response equipment and resources since no community can own and maintain all of the resources that might be needed to respond to any given event,” according to the North Carolina Department of Public Safety (NCDPS) website.

The Mutual Aid System allows for cost-free sharing of resources, although an NCDPS spokesperson said it is used less for emergencies and more for routine resource sharing. The state’s emergency process after large-scale disasters, including after Helene, requires resource transfers within the state to be documented with the expectation they will be reimbursed later by federal dollars.

There is also an interstate mutual aid agreement called the Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC), which was activated in the aftermath of Helene, according to a retrospective report on the state’s emergency response. At Mountain Heritage High School in Yancey County, the parking lot could be seen full of first responders from across the state and the country — police officers from Matthews, North Carolina, and firefighters from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Mutual aid during the storm

Hurricane Helene brought three days of extreme rainfall to western North Carolina, with some gauges recording precipitation in feet rather than inches. Major rivers and creeks surged and overflowed as water funneled in from the mountainous terrain, whose soil was already saturated from a previous storm. The widespread flooding swept away houses, lifted pavement off the ground, felled trees and power lines, triggered mudslides, and killed more than 100 people.

Earlier in the week, residents were already reacting. The night before the hurricane hit, flooding threatened Mitchell High School. “Custodians, SROs, maintenance, coaches, board of education, school administrators, central office, Ledger Fire Department, and Tanner Winchester from Vannoy Construction” all worked together in the rain to prevent damage.

Mitchell County Schools Superintendent Chad Calhoun had access to a Starlink user terminal. He connected via satellite with people outside North Carolina before the hurricane hit to arrange for help, including from Troyer’s Country Market which provided breakfast, lunch, and supper at the new Mitchell Elementary/Middle School on a first-come, first-served basis for weeks following the storm. On the first night, they served 850 plates.

Further north, help was underway during the night of the storm. At a K-8 school in Valle Crucis, school staff spent Friday night holed up in classrooms, pumping floodwater out of the building until the power went out. Carter Dishman, part of the team that spent the night in the school, later ran an aid distribution site at Bethel Baptist Church.

The following morning, across western North Carolina, residents emerged with chainsaws to clear their neighbors’ downed trees, hooked up generators, and cooked big meals on portable stoves. They joined impromptu search teams, hoping to account for everyone in their communities. They sheltered those whose homes had been damaged or destroyed. Many had equipment and supplies for emergency situations — a mark of mountain preparedness — but many others were unprepared for such an event.

Despite the advanced warning of the incoming storm, its severity took many by surprise. The need for aid was immediate and massive.

How aid flowed after the storm

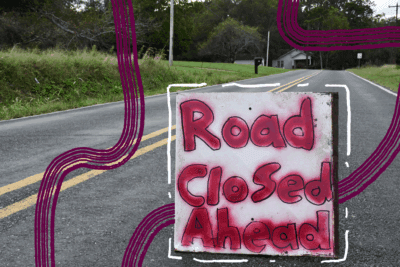

One of the first problems was the difficulty of free movement. Most western North Carolina counties are sparsely populated and composed of winding, narrow roads. Downed trees and power lines, washed out highways and collapsed bridges, and high water levels prevented people from reaching each other and from reaching aid.

As paths were cleared, the power was still out and communications were down. People gathered in instinctual places, including fire stations, churches, schools, and the Blue Ridge Parkway, which in some areas was the only place with cell service.

In the absence of cell service or emergency communications infrastructure, information flowed through posted signs and word of mouth. A message scrawled on an envelope taped to the front door of the Yancey County Schools building notified those who found it of a Sunday meeting. School staff put whiteboards throughout town to communicate with parents and left sticky notes on each other’s cars.

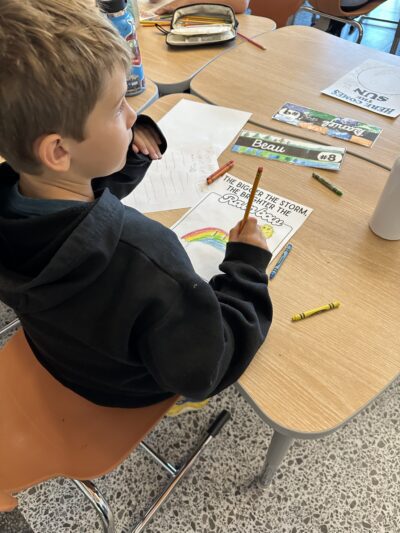

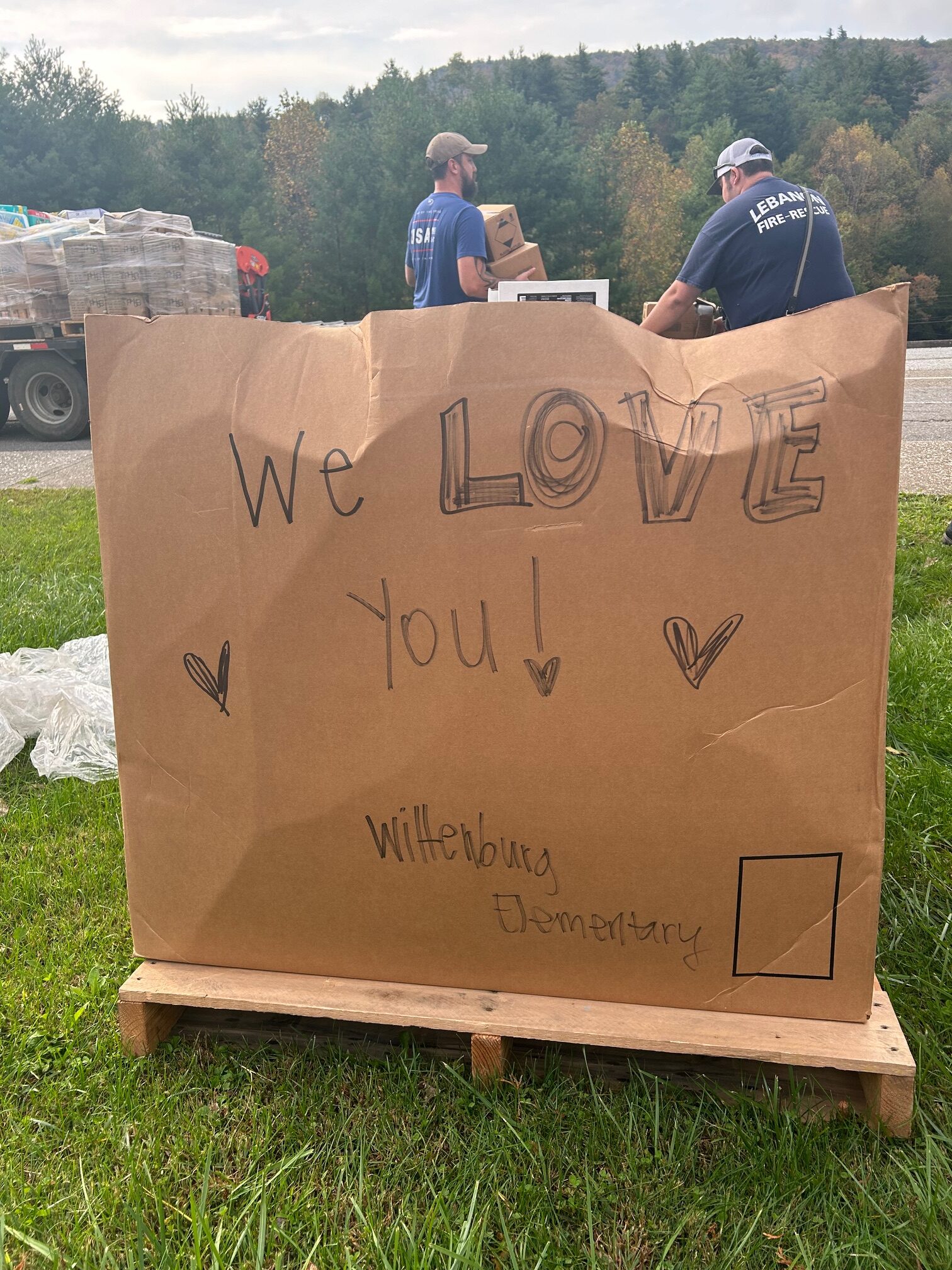

At schools, teachers, parents, administrators, staff — and really, anyone — showed up ready to act. Soon after, supplies appeared. Piles grew larger and larger. Community members became workers; the first relief aid distribution sites began operating. Jobs went to volunteers as needed, including one educator who learned to operate a forklift.

Nonperishable food, bottled water, and clothing were soon mountainous in hallways, classrooms, gymnasiums. Later, generators, portable heaters, and blankets came in, along with easily overlooked necessities: at least one school received donations of hay to feed hungry livestock.

Schools on the front lines

Michelle Lord, a now-retired Exceptional Children (EC) teacher, walked into her classroom in Mitchell County a few days after the storm. She found cots, bags, and members of Virginia Task Force 2, a search and rescue team under the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

The team was working out of her school, sleeping there and venturing out during the day to account for people and deliver aid. They asked Lord to ride along because they didn’t know where to take supplies.

She started going in every morning at daybreak to accompany the team, in a box truck packed with food and water, around Mitchell County. She lost track of the days. “Time didn’t seem to matter much,” Lord said.

Reflecting on those days distributing aid, she said she realized her role was sharing community knowledge and needs.

“You know your community, you know your students, you know your area,” she said. “You just did it. We just did it. It’s hard to say why you did it. Yeah, I don’t know. We just did what had to be done.”

Lord was one of many. School staff were prepared for the job — they knew where their students lived, they knew family needs (medication, dietary restrictions, mobility issues), and they were a familiar face for children in a frightening situation.

Jennifer Gregory, associate superintendent of Mitchell County Schools, said schools were the backbone of aid efforts in her county. She recalled a teacher who had recently given birth unloading supplies with her child nearby in a carrier.

“Our teachers and staff — our school staff — ran probably 90% of our distribution centers in the county,” she said. “We had staff who walked miles into Pigeonroost and Poplar, where it was completely devastated, taking supplies.”

In neighboring Yancey County, schools also acted as distribution sites. Dr. Brent Laws, principal of Burnsville Elementary, said his school became an aid distribution site on the Tuesday after the storm and remained one until a week before students returned to school a month and a half later.

On that Tuesday, a semitruck arrived packed full of toiletries, food, and clothing. Soon, tents were pitched, hallways were clogged with supplies, and a massive operation was underway. Laws said his school was a natural place for such an effort.

“We were almost a distribution site by default,” he said.

His school housed hundreds of electrical lineworkers from across the country; helicopters landed in the adjacent field; food trucks distributed free hot meals every day for weeks.

A groundswell of aid

Aid was delivered from many places — as far away as Canada and other distant states. Laws said 15 families at his school had homes that suffered irreparable damage; some were gifted RVs sent from Texas by a donor.

Aid also came from central and eastern North Carolina and the surrounding affected states of Tennessee, Virginia, and South Carolina. Often, supplies — that, to the distributors’ eyes, appeared out of nowhere — had been ferried west from the Triangle, from Charlotte, from Wilmington. People drove up into the mountains with filled gas canisters and toilet paper in the trunks of their cars.

Money was also transferred west, often through Venmo as a result of grassroots social media campaigns. It was pooled and spent on supplies which were then dropped at distribution sites by volunteers, or it went directly to on-the-ground organizations such as fire departments. (On at least one occasion, donors were targeted by fraudulent Venmo campaigns.)

And finally, aid came from within western North Carolina. Lesser affected areas sent extra supplies to the hardest-hit places, both through uncoordinated and coordinated personal donations, and through institutional relationships. An example: After the immediate needs from the storm had settled, Ashe County Schools sent Yancey County Schools about 200 hams for Easter.

People with extra food stocked in their pantries brought it forth for others, including by transferring it through the EdNC team. They donated equipment, time, and money. They traveled at their own risk through dangerous conditions to ensure others were cared for. They knew their neighbors would do the same for them, and they did.

Pride can be a barrier to receiving support

Community knowledge and preexisting personal connections played a role in the effectiveness of aid distribution, organizers said. Beyond the knowledge western North Carolina residents brought to the operations, they destigmatized and cushioned the sometimes uncomfortable process of asking for help.

Western North Carolina, mostly rural and mountainous, separated from major routes and urban centers, has a distinct culture. Organizers said that in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene, some refused aid out of a sense of self-sufficiency.

“Someone else might need it more than I do,” was a common refrain. Many took convincing that they were in need even as supplies piled high in distribution centers. The volunteers who staffed distribution centers were hesitant to take supplies as well, organizers said.

That mix of pride and selflessness was one barrier to effective aid distribution. But with persistence, those in need accepted help, and any taboo that might have been in the air quickly dissipated as community needs were validated from within — and as the severity of Helene’s widespread destruction was revealed.

Read more about Helene recovery

Gaps in aid, and how communities responded and led

Some people refused help, didn’t seek it out, or didn’t find it for other reasons.

In many counties in western North Carolina, Hispanic residents are the largest population of color.

“We haven’t received anything. I heard they supposedly said that they sent help, but the truth is, we haven’t received anything,” one Mitchell County man said in Spanish.

In the early days of recovery, some people who didn’t speak English had trouble understanding emergency broadcasts, understanding the process for home inspections, and even communicating with neighbors. Translating between Spanish and English often wasn’t possible without power or cell service.

Laws, the principal of Burnsville Elementary in Yancey County, and Nancy Martinez, the school’s secretary, were conscious of this language barrier. According to Laws, 27% of students at Burnsville Elementary are Hispanic, while other Yancey County schools’ percentages of Hispanic students are “single digits at most.”

Under normal conditions, Martinez greets students in both English and Spanish at the front door of her school. As part of aid distribution efforts, Martinez and others who speak Spanish worked to spread information to families that didn’t speak English.

“We tried to get together as a group and communicate things to everybody that we were able to reach,” she said.

In nearby McDowell County, the Marion-based organization Centro Unido Latino Americano lobbied for emergency messages to be bilingual and requested bilingual FEMA workers to their offices.

Beyond language difficulties, there was a fear among some Latinx people that prevented them from seeking out aid.

EdNC’s CEO Mebane Rash said that fear kept some families from feeling like they could go to a distribution site, and informal sites popped up as a result. She visited one such site for migrant families adjacent to an apartment complex. Leaders of the community, she said, struggled to figure out how to staff it as they balanced their own challenges post-Helene and their jobs at local farms.

“There were many people who were — we were afraid of going out because, well, we are undocumented,” one woman said in Spanish. “We don’t have a way to identify ourselves, right? A lot of people didn’t come out because they were scared.”

Some people were scared of large gatherings or encountering government workers, disqualifying the idea of visiting distribution sites. The woman said the closest she came to interacting with officials was hearing the sound of helicopters overhead, delivering aid elsewhere.

In the neighborhood where she lived, food, water, blankets, and clothing were brought from distribution sites by community volunteers and stored in a house that neighbors felt they could safely access.

“It was a house of refuge,” the woman said.

A symptom of existing inequities

Carlos Lopez was a community health worker with the Williams YMCA of Avery County at the time of the storm. The YMCA, like many other community spaces, was housing National Guard, search and rescue personnel, and piles of supplies.

As he hauled supplies up mountains and coordinated distribution efforts, Lopez witnessed the hesitancy among Latinx people. He saw it as a symptom of existing inequities, saying people who hadn’t already been brought into community networks were harder to reach.

“The hurricane helped to filter out folks who weren’t already getting the help before the hurricane,” Lopez said.

Throughout the disaster area, FEMA workers were stationed at aid distribution sites and other community locations to help people apply for federal aid. However, applying requires a social security number, which immigrants without legal status don’t have — meaning they couldn’t qualify for help.

Lopez said the preexisting network of community health workers and locals could sometimes fill the gap.

“Some folks had their homes completely destroyed by either the water, landslides, or trees, and those were the kind of things that it would have been nice for some federal agent to help these folks. But with the whole system in place, the guidelines and all that, they were not able to, at least not everyone,” Lopez said. “So there was a lot of work around that. We tried. But ultimately, you know, it had to come down to local aid.”

Before working at the YMCA, Lopez was a youth organizer for the aforementioned Centro Unido, a nonprofit “devoted to creating educational, economic, and recreational opportunities for the Latinx community,” according to its website.

He said Centro Unido, as a trusted community organization, became an “enormous player” in direct relief efforts in McDowell County and surrounding areas in the aftermath of Helene.

“When times of disaster and crisis strike, the role that these organizations play in a lot of these community members’ lives gets an extra layer of deepness, if you will, because now there is a dire moment of need, rather than just needing food for this week, or ‘I need help with my water bill or my electrical bill this month.’ It far exceeded that, it went way deeper than that,” Lopez said.

The executive director of Centro Unido, Margarita Ramirez, helped coordinate an aid distribution site out of McDowell Technical Community College, and word spread that it was a safe place to receive help.

“They were really afraid,” Ramirez said. “(There was) fear because of the storm, fear because they lost their home, and then on top of that, there was fear of the federal government agencies that haven’t been friendly to them before.”

Border Patrol and Immigration and Customs Enforcement vehicles were spotted in western North Carolina after Helene, which Ramirez said was intimidating.

Direct financial aid

Centro Unido and other organizations, and distribution sites like schools and churches, hosted FEMA workers who helped families apply for federal monetary aid based on damages and insurance coverage.

As applications were approved and federal dollars started flowing to households, immigrants without legal status who couldn’t apply were left without direct help. (Mixed immigration status households are eligible for federal dollars.)

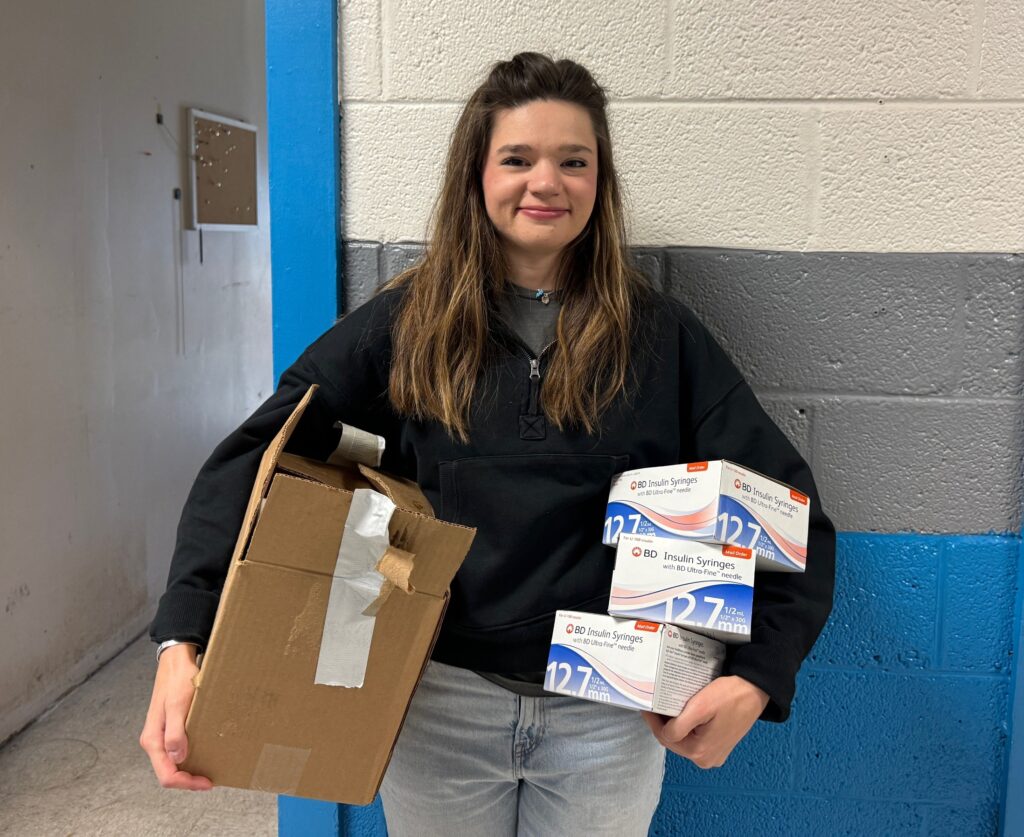

Ramirez saw the need for cash assistance in her community among those without legal status, but also among the vast number of others waiting on FEMA awards to be disbursed. Centro Unido started a program called The Jireh Project which granted between $400-$5,000 to people who had suffered damage to their homes, job loss, or delays in payment of utilities in Mitchell, Burke, McDowell, and Buncombe counties.

“We just wanted to make sure that people had money in their pocket to do what they needed to do, because FEMA was taking forever to respond. We had families sleeping in their car. We had families (whose) mobile homes got flooded and they had nowhere to go,” Ramirez said. “My goal was to actually put money in their pockets again, with no limitations.”

The amount Centro Unido awarded depended on the situation — less money for loss of food, more for damage to property. Ramirez said Centro Unido staff visited applicants’ homes to verify their need, and usually handed out checks within four or five days of application. The money had no qualifiers and could be used for anything.

“They were really happy. I mean, that was a fast response, compared to (FEMA),” she said. “We injected close to a million dollars into the community — direct checks.”

Government funding of aid comes with strings

Samaritan’s Purse is another organization that operated in western North Carolina after Hurricane Helene. The religious organization has committed to embedding long-term in Helene-affected areas and has constructed or repaired hundreds of homes, according to its website.

Samaritan’s Purse volunteers, who can be recognized by their bright orange shirts, also cut downed trees, hauled debris, and shoveled mud in the days after the storm. The organization set up a field hospital and airlifted emergency supplies to stranded North Carolina residents.

At a Hurricane Response and Recovery Subcommittee meeting in September 2025, Rep. Brenden Jones, R-Columbus, criticized the state response to Hurricane Helene. He noted that, six months after the storm, not a single house had been rebuilt under the state’s Helene housing program. The program is funded by a federal grant with a process that requires multiple steps of approval before it can be implemented.

The meeting also highlighted other federal delays that have impacted North Carolina’s hurricane response. Gov. Josh Stein announced in August 2025 that the first repairs had been completed, but at the time of the September meeting, a new house hadn’t been constructed through the state program.

Jones questioned whether state government funds should go directly to nongovernmental groups because, he suggested, they can move faster and circumvent “bureaucracy and red tape.”

However, Samaritan’s Purse specifically chose not to accept state funds because of the requirements that come with them.

“We do not want any government funding. That’s no red tape, no restrictions, no reporting. We report to our accountability, our auditors and so forth, but we can get the dollar into the homeowners hand, I think, faster,” a Samaritan’s Purse representative said at the meeting.

Matt Calabria, director of the Governor’s Recovery Office for Western North Carolina, noted that while Samaritan’s Purse declined state funds, the state has funded similar organizations. He said, as examples, that $3 million went to Habitat for Humanity and $6 million went to Baptists on Mission for home repair.

“Speaking from experience, it’s really the only way that some of that work is going to get done,” said Jonathan Krebs, western North Carolina recovery advisor to Stein.

Philanthropy’s role in funding mutual aid networks

When Hurricane Helene struck, the Community Foundation of Western North Carolina (CFWNC) quickly mobilized — thanks to an outpouring of support from across the country and beyond — distributing more than $39.6 million in more than 525 grants, many of which supported the preexisting and new mutual aid networks needed to support relief and rebuilding.

CFWNC is a nonprofit that maintains a permanent pool of charitable capital and helps facilitate philanthropic donations in 18 western North Carolina counties and the Qualla Boundary. Elizabeth Brazas, president and CEO of CFWNC, said their emergency fund was opened up shortly after the storm once staff got access to power and internet.

Centro Unido was one organization to receive grants from CFWNC: one for $25,000, which supported the distribution of essential items; and the other for $250,000 to provide direct housing assistance to individuals and families in Buncombe, Burke, McDowell, and Mitchell counties.

CFWNC also funded schools and school districts directly. Grants awarded with strategic support from EdNC went toward helping districts like Avery County Schools meet the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction’s requirements for reopening schools.

More than a year later, the takeaways and lessons learned from mutual aid after Helene

What Came With Helene:

Destruction, despair, desolation, death.

What Came After Helene:

Hard work, struggle, sweat,

Tears, thanksgiving,

Hope, joy,

Families coming together,

Neighbors helping neighbors,

Strangers becoming friends.

Our beautiful little mountain communities may look different, but we are strong, mountain people. Our ancestors fought to survive here and we can be proud of who we are and where we came from. We will rebuild together. Our communities will be beautiful again because they are already beautiful from within ourselves.

There are no words to express the deep gratitude that we all have for everyone from near and far who has shown concern, prayed, sent donations (whether monetary or in the form of food or supplies), those who have showed up to cut down trees, knock on doors, and lend a hand in any way possible. We will never forget what you have done for us.

— Laura Cole, a band and music teacher in Mitchell County

In the wake of Hurricane Helene’s devastation and the vigorous community aid response to it, there were lessons learned. Practical improvements that some places are making to be better prepared in the future include storing generators in schools, drilling wells, and having more robust satellite communications systems at the ready.

But a broad lesson is that mutual aid — or community-driven aid or direct aid — is necessary and effective, no matter what it is called. Trust among neighbors allowed aid recipients to accept help and allowed aid to be targeted to needs. It shortened distances and didn’t necessarily rely on faraway outsiders, allowing timely support. It put those affected by the disaster in the front seat and restored their agency as a community.

Strong community ties were vital, especially in the beginning hours of recovery when people’s movements were somewhat autonomous, standing up aid distribution hastily — but not haphazardly. The role of schools as anchor institutions in the communities they serve took on a renewed prominence, along with churches and other community spaces.

Hurricane Helene brought sadness and destruction; the human reaction to it brought beauty. There was a spirit in the people rescuing and rebuilding — it came through in the timbre of their voices. If there is a key ingredient to community, it is people supporting each other.

Behind the Story

- Only in unusual circumstances does EdNC rely on anonymous sources. In this case, EdNC reporters met in person with the sources, who are not named due to safety reasons.

- In this story, collective attributions to “organizers” are based on interviews with mutual aid organizers across many western North Carolina counties.

Recommended reading