Last week, I had the opportunity to share some of my Constitutional Tales with the Public School Forum’s Study Group XVI — Educational Opportunity. These tales centered on the inequities created in education during the Aycock era in the early 1900s.

Afterwards, Dr. Dudley Flood approached me about whether the presentation was available in writing. I apologetically told him no. That afternoon, I had an email from Dr. Terrance Ruth — another EdNC writer — who expressed interest in the materials as he was exploring issues of education and race. I told him the same thing. The next day, Mebane Rash asked me if I would turn the presentation into an article. After eight years of giving presentations, it seems to be time to do this.

I dedicate this effort to Dr. Flood and to his extraordinary legacy and continued work for this State on race equity and relations. And I offer it to all of you who join Dr. Flood in this vital work for the State.

As context for discussing educational opportunities at the turn of the twentieth century, it is worth remembering the fundamental principles of the 1868 Constitution.

A coalition of delegates to the 1868 Constitutional Convention, comprised of Blacks and local and out-of-state Whites, framed a constitution that established a right to the privilege of education and the requirement of a general and uniform system.

That coalition went out of power quickly with a resurgence of those who had been in control before the Civil War. Other fusion efforts emerged later in the 1800s and Black males exercised their right to vote.

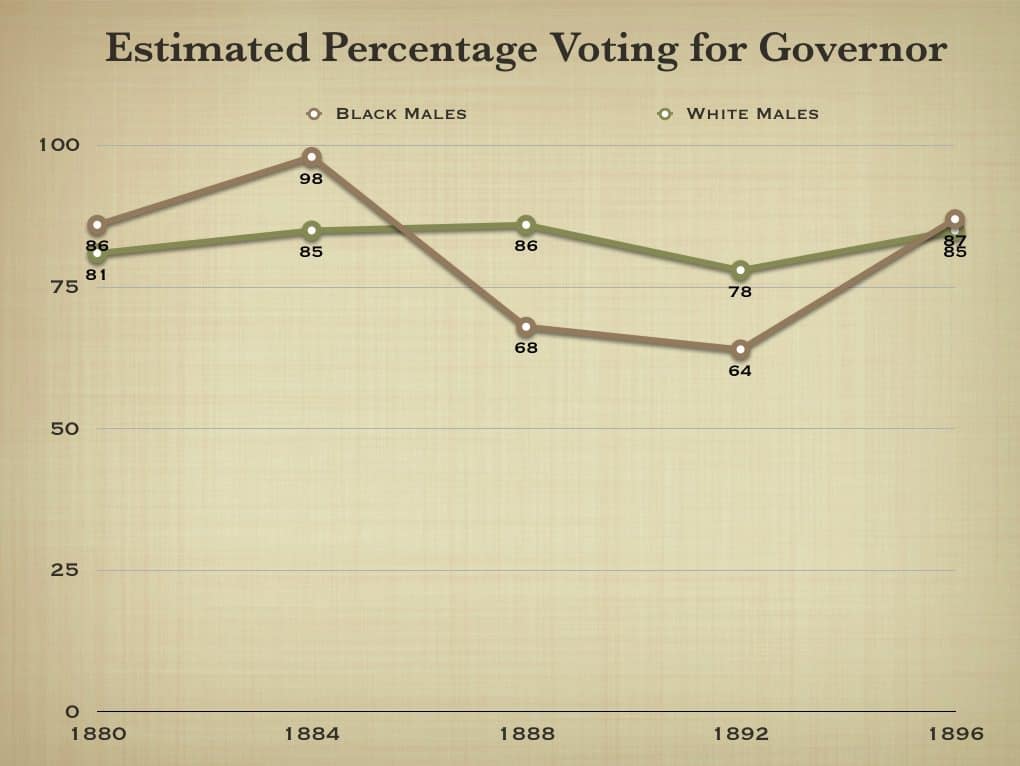

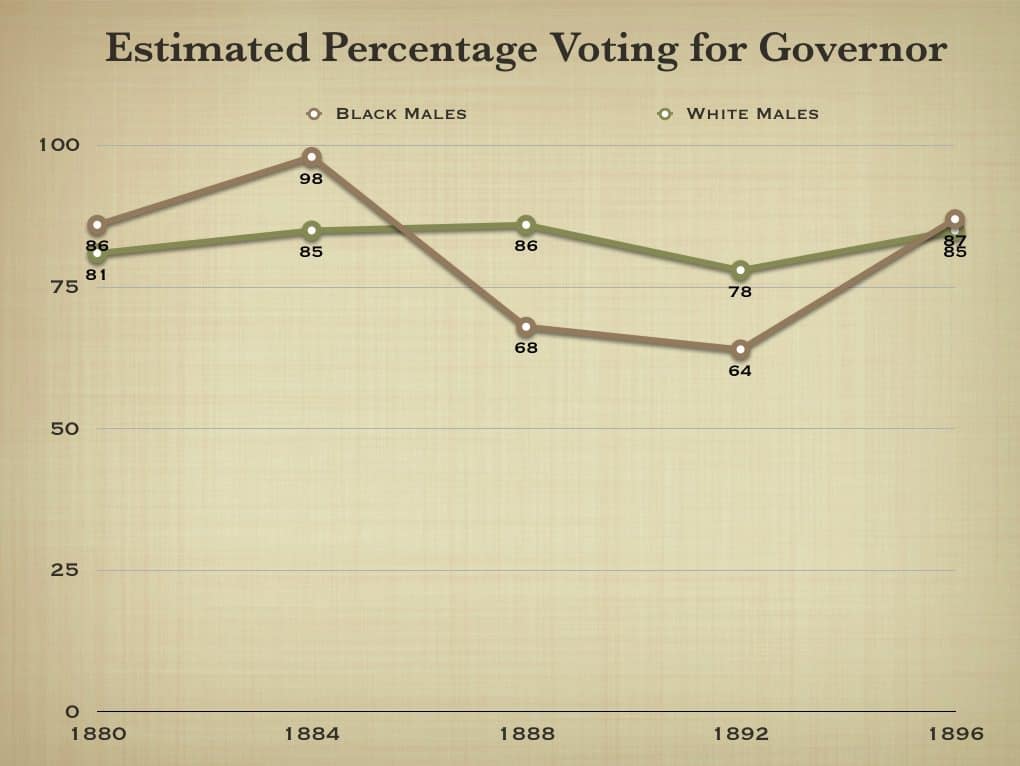

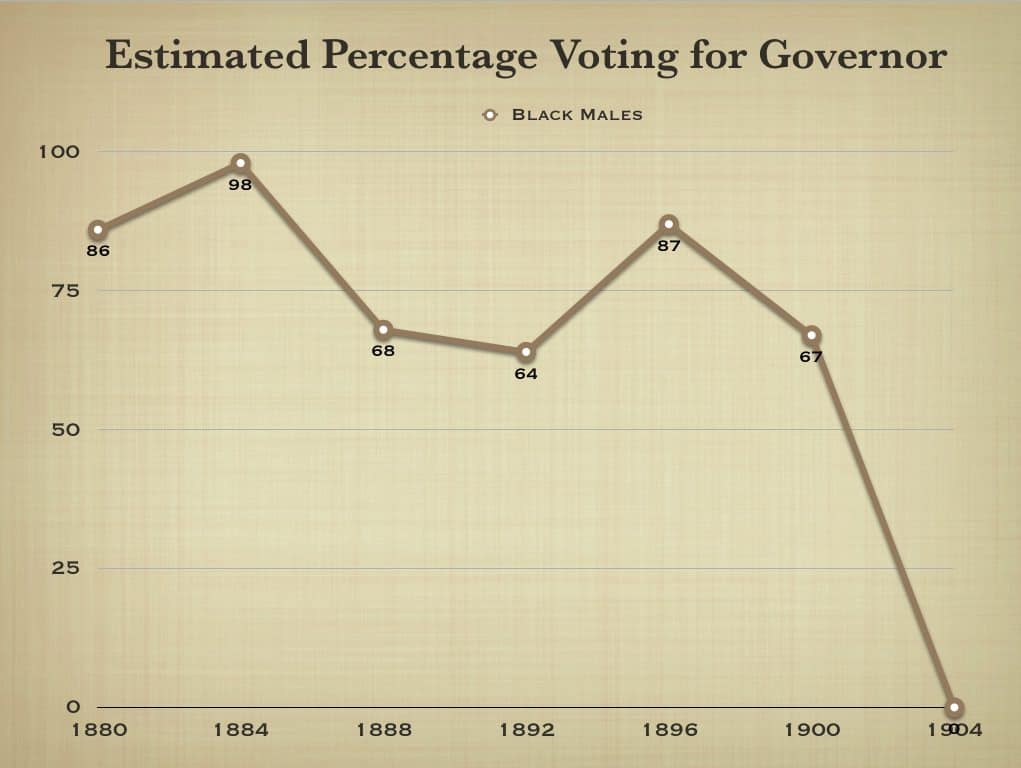

Look at these voting patterns in the late 1800s:

Remarkable aren’t they? Look how high they are for Black and White males — up to 98 percent for Black males in 1884. The dips in 1888 and 1892 are caused by voter intimidation — deliberate efforts to reduce the impact of the Black male vote.

These voting patterns have a particularly strong effect in the eastern part of the state where Blacks are a substantial proportion of the population — sometimes in the majority.

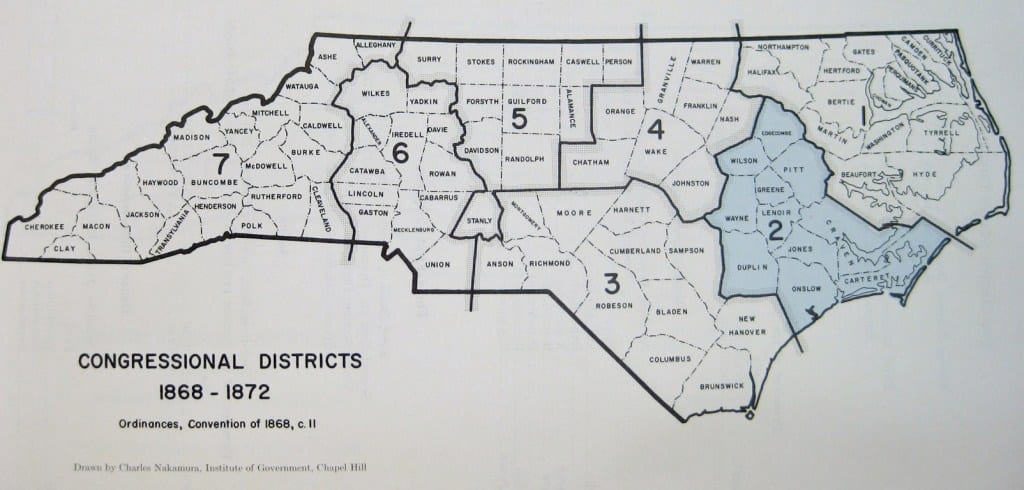

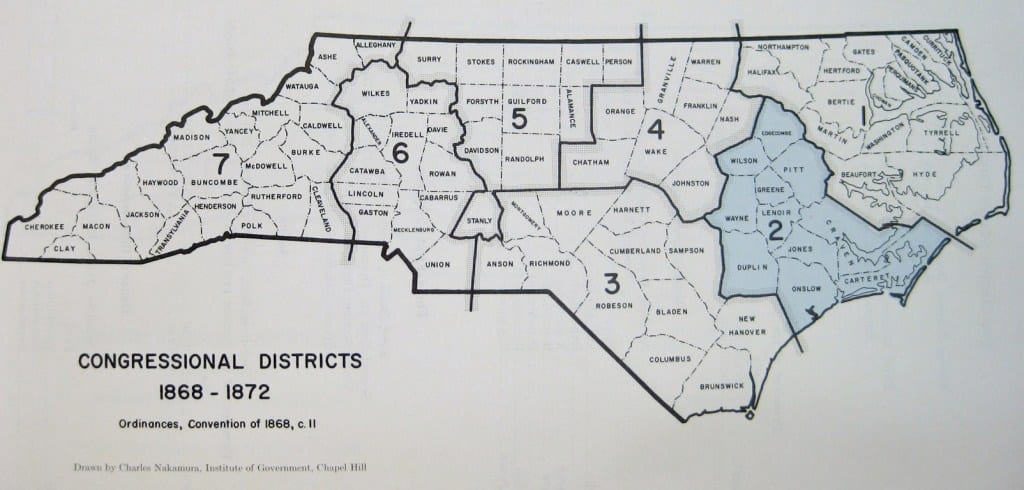

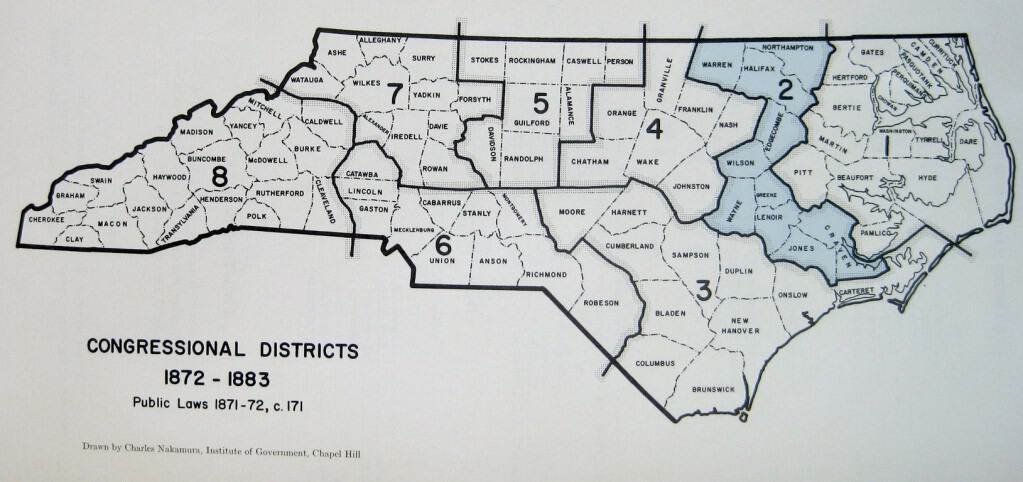

To reduce the overall impact of the Black male vote, conservative Democrats gerrymander the Second District. In this congressional district map in effect from 1868 to 1872, each district looks like a puzzle piece — a reasonable effort to carve the state into districts.

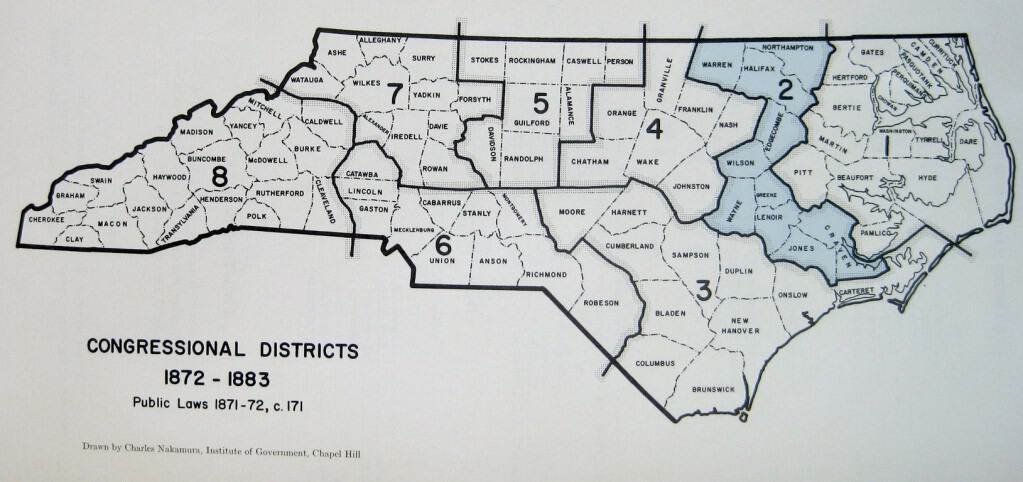

Compare this to the reconfigured Second District in place from from 1872 to 1883.

The counties in the Second District were 40-70 percent Black. By concentrating the Black vote in one district, it allows White democrats to get into office in the other districts. The Second District is essentially ceded to Blacks.

And for 28 years, Republicans rule this district and a number of Black congressmen are elected. (Note: political parties in the United States have a complicated history with party labels reflecting different political platforms over time.)

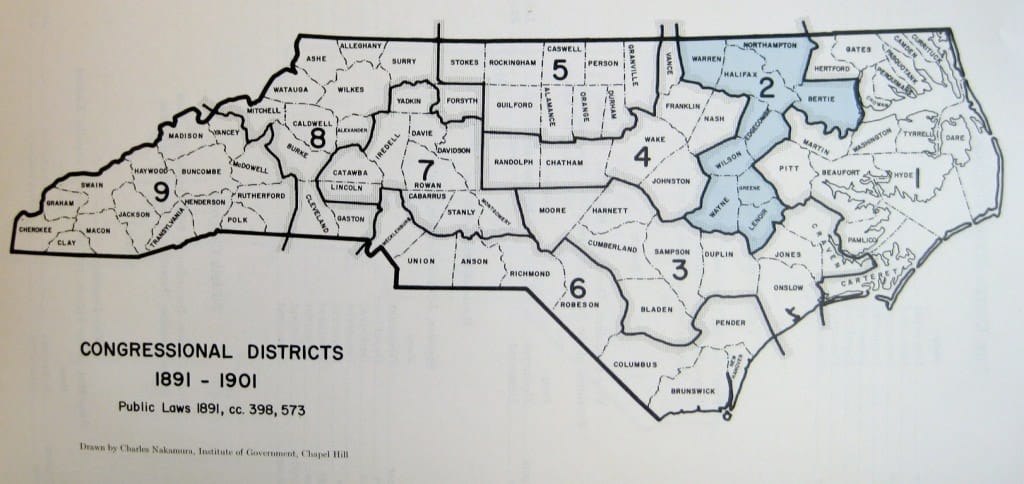

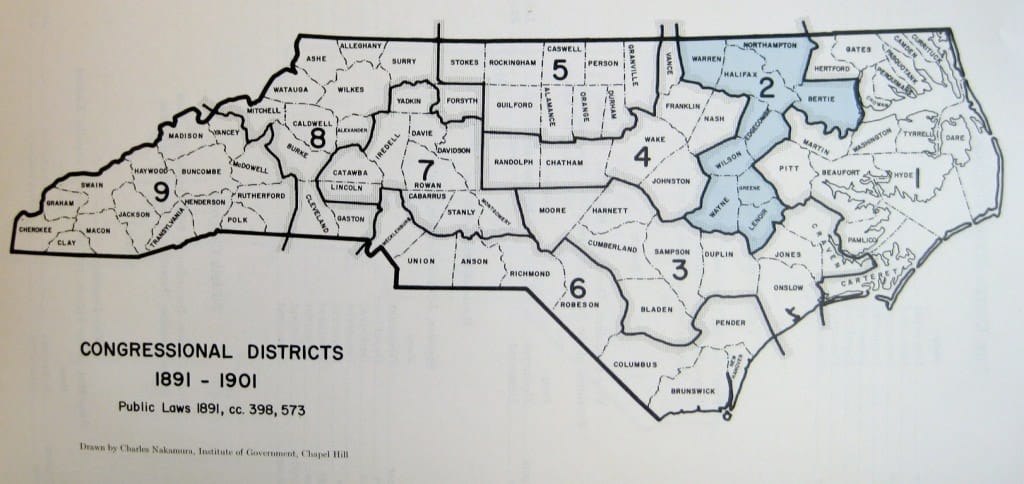

The Congressional district lines are redrawn several times to fine tune this configuration so that leading to the gubernatorial elections in 1900, the Second District is carved out as follows:

For White political aspirants, the Second District reflects their greatest fears of what they call “Negro domination.”

It is not surprising that the Second District is where the White Supremacy campaign emerges in full force.

Charles B. Aycock, of Wayne County (in the Second District) is its leader. In 1898 he is instrumental in the coup d’etat in Wilmington, also referred to as the Wilmington race riots. As the Democratic candidate for governor, he prepares a platform for his election that includes suppression of the Black vote.

Here is part of his address in accepting the nomination as Governor by the Democratic Party in 1900:

“We have taught them much in the past two years in the University of White Supremacy, we will graduate them in August next [date of election of governor] with a diploma that will entitle them to form a genuine White man’s party. Then we shall have no more revolutions in Wilmington; we shall have no more dead and wounded negroes on the streets, because we shall have good government in the State and peace everywhere. But to do this we must disfranchise the negro. The amendment to the Constitution is presented in solution of the problem. The Democratic party knows the truth — it is certain that the unlettered white man is more capable of government than the negro.”

The constitutional amendment he speaks of is the literacy test. To be eligible to vote, this test requires a person to be able to read and write any section of the constitution.

In order for Whites who are illiterate to continue to vote, there is a grandfather clause for those who are descendants of persons who have been entitled to vote. This clause expires, however, and is only available for those who register to vote by December of 1908.

Aycock explains this in his nomination acceptance speech:

“But the opponents of the Amendment attack it on another ground. They say that every child who comes of age after 1908, white and black, must be able to read and write before he can vote. This is true. The schools are open and will be for four or more months every year from now to 1908. The white child under thirteen who will not learn to read and write in the next eight years will be without excuse. I tell you that the prosperity and the glory of our grand old State are to be more advanced by this clause than by any other one thing.”

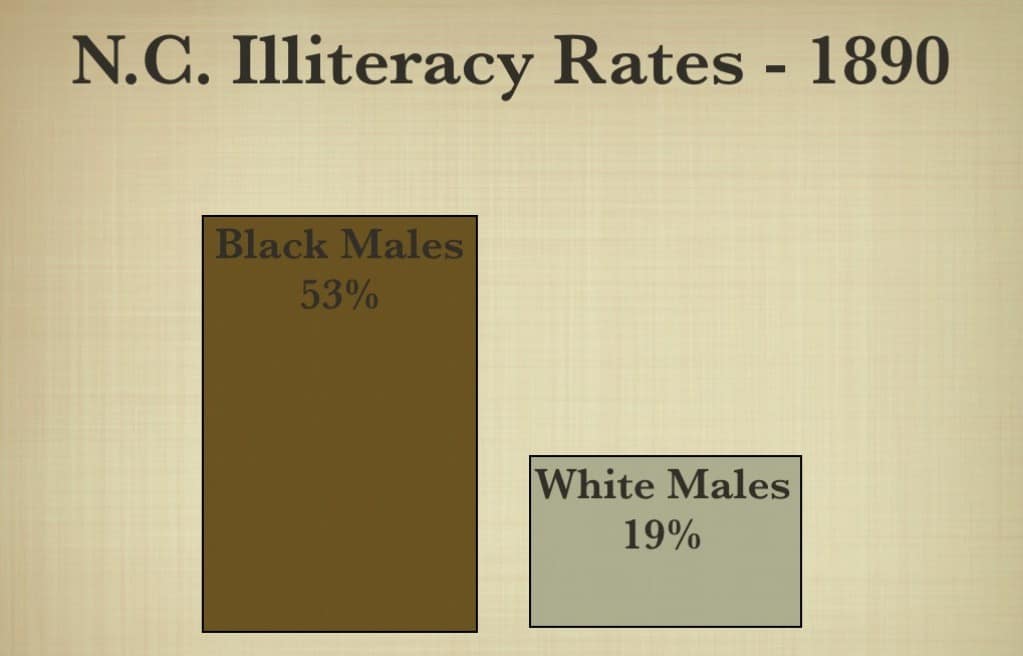

The illiteracy rates help explain why Aycock chose this strategy.

As a tactic for disfranchising Blacks it will be effective, especially coupled with voter intimidation. The fear among Whites is also easy to understand given the large percentage of illiterate Whites.

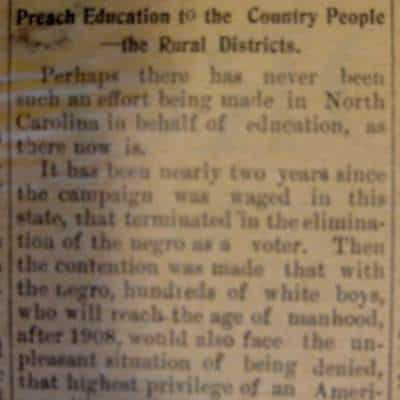

Aycock is a former educator and served as superintendent of schools in Wayne County. The 1908 deadline creates leverage for what becomes known as the great campaign for education.

Aycock is emphatic about this in his nomination speech:

“Speak the truth, ‘tell it in Gath, the streets of Askelon’ that universal education of the white children of North Carolina will send us forward with a bound in the race with the world. With the adoption of this Amendment after 1908 there will be no State in the Union with a larger percentage of boys and girls who can read and write, and no State will rush forward with more celerity or certainty than conservative old North Carolina.”

Due again to voter intimidation in 1900, the Black vote drops to 64 percent. In this election, Aycock is elected governor and the constitutional amendment to add a literacy test passes 59 percent to 41 percent.

The literacy test serves its intended purpose of disfranchising Blacks.

At the next election, when the literacy test is in effect, the percentage of Black males voting is virtually 0 percent.

Now the governor must meet his campaign promise of helping Whites become literate so that children who come of age after 1908 will be able to pass the literacy test.

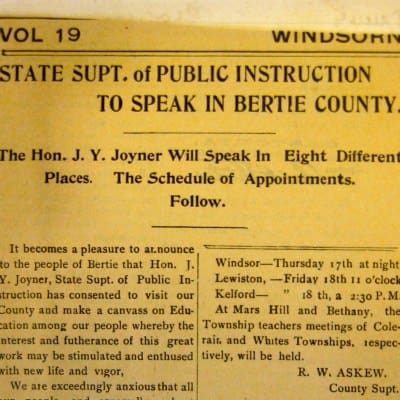

The Capitol is the campaign headquarters. Under Aycock’s direction, the Central Campaign Committee is established. A key element of the campaign is to build community support for schools. In 1902, James Y. Joyner becomes State Superintendent and takes over the campaign.

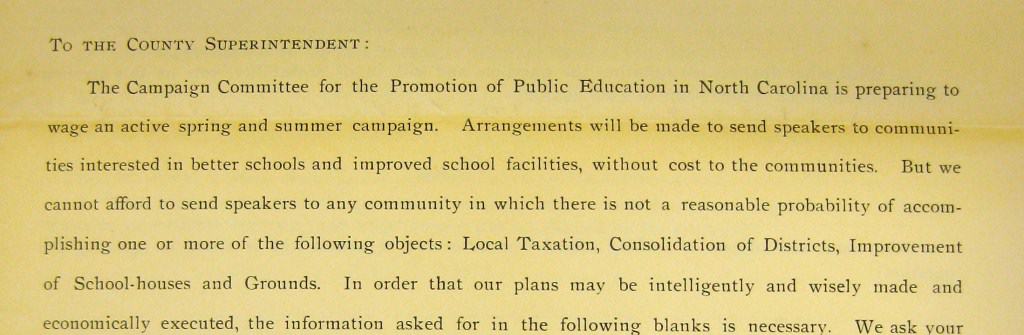

As a part of the campaign, they send a survey to county superintendents and offer to come speak at rallies. Here is an excerpt from one of these documents:

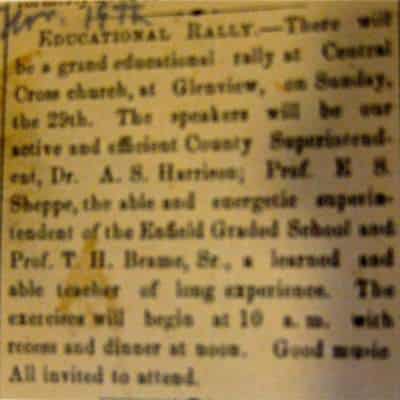

Such rallies are held across the state.

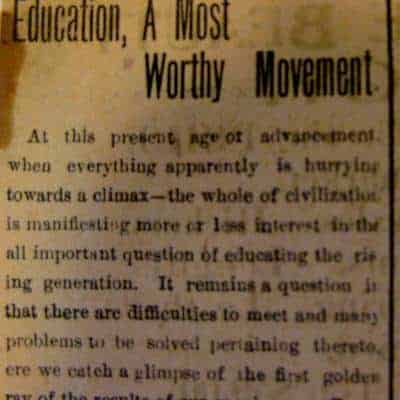

Newspapers carry editorials in support of the education campaign, like this one of the Messenger-Intelligencer in Wadesboro, NC in 1908:

“Next Monday will be an important day in Anson, the county board of education having decreed that all the public schools of the county shall open their doors that day … It is a painful truth that many of our people have not, in the past, taken that lively interest in public education which its importance demands.

The white parents of the county should be informed that their children, who come of age after 1908, cannot vote unless they can read and write. … Surely there is no white parent in Anson County who wishes to see his little boy grow to manhood and not have the privilege of casting a ballot for the party of his choice.”

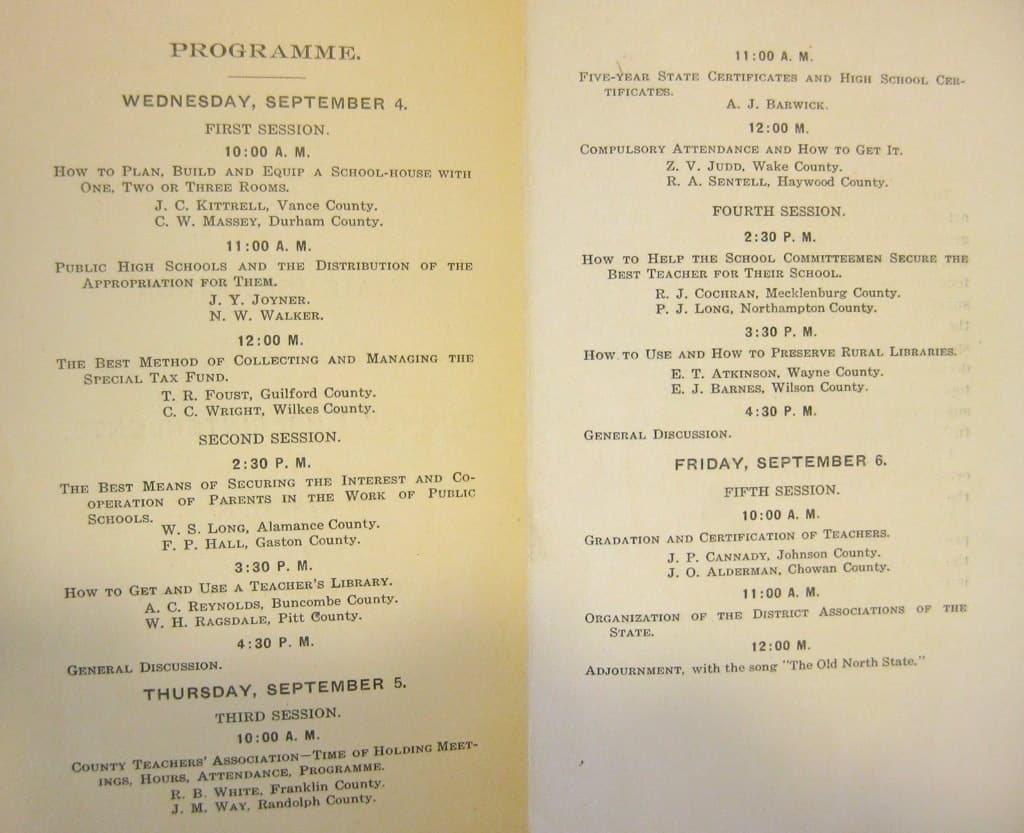

In addition to this campaign with the public, J. Y. Joyner works closely with local superintendents in order to build capacity for education. He meets regularly with them, including at this meeting of the State Association of County Superintendents, held in Montreat, NC, September 4-7, 1907.

Here is the agenda for this meeting:

The agenda includes the best means of securing the interest and cooperation of parents in the work of public schools; compulsory attendance and how to get it; and how to help the school committeemen secure the best teacher for their school.

On Wednesday at 12:00, the agenda provides for addressing “the best method of collecting and managing the special tax fund.” Local tax districts allow taxes to be targeted to a small community to benefit the schools just in that community. It might even be just for one school.

This is a major strategy for raising targeted funds. As a result of the state-wide initiative, the number of tax districts grow from 7 in 1899 to 402 in 1906 to 1,534 in 1913.

Superintendent Askew of Bertie County reports on one of these superintendent meetings to his local newspaper as a front-page story.

“It is remarkable to note that, of the 97 County Superintendents in the State, 92 were present and answered to their names.

Without doubt, this large attendance was due, to the influence of the positive and decided character of State Superintendent Joyner. The whole state seems alive to the need of better school buildings, better teachers, longer terms, local tax helps and graded school establishment.”

We need to tell the whole story, however.

While local tax districts helps education in some communities, it creates disparities with poor or minority communities that could not afford additional taxes.

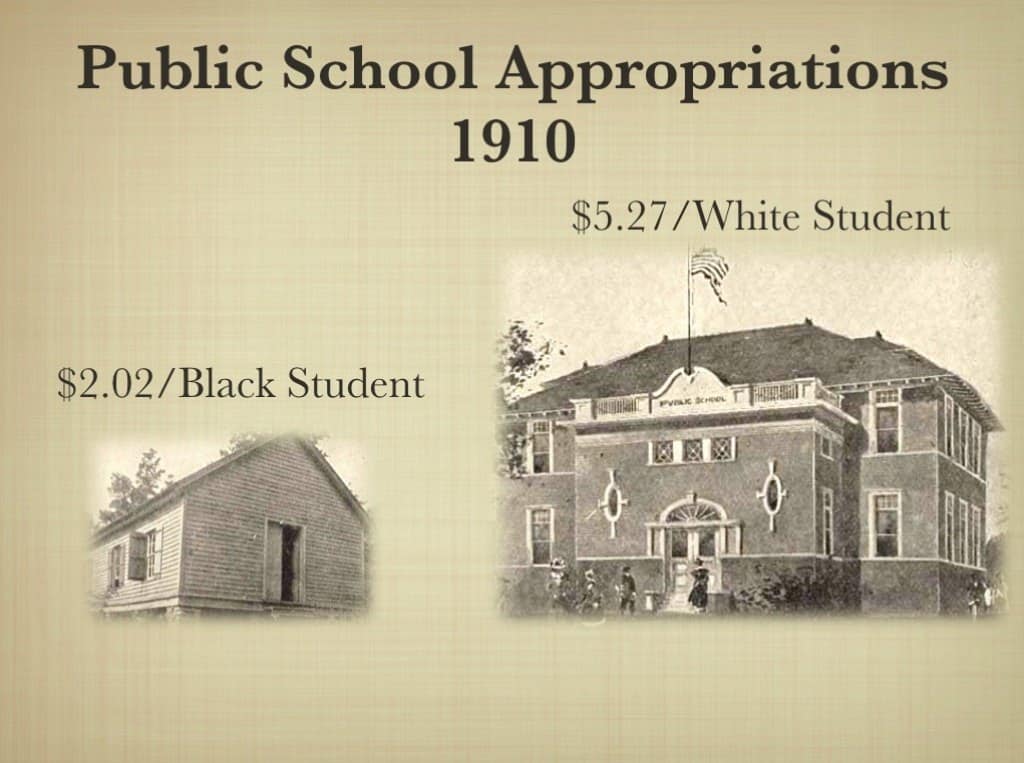

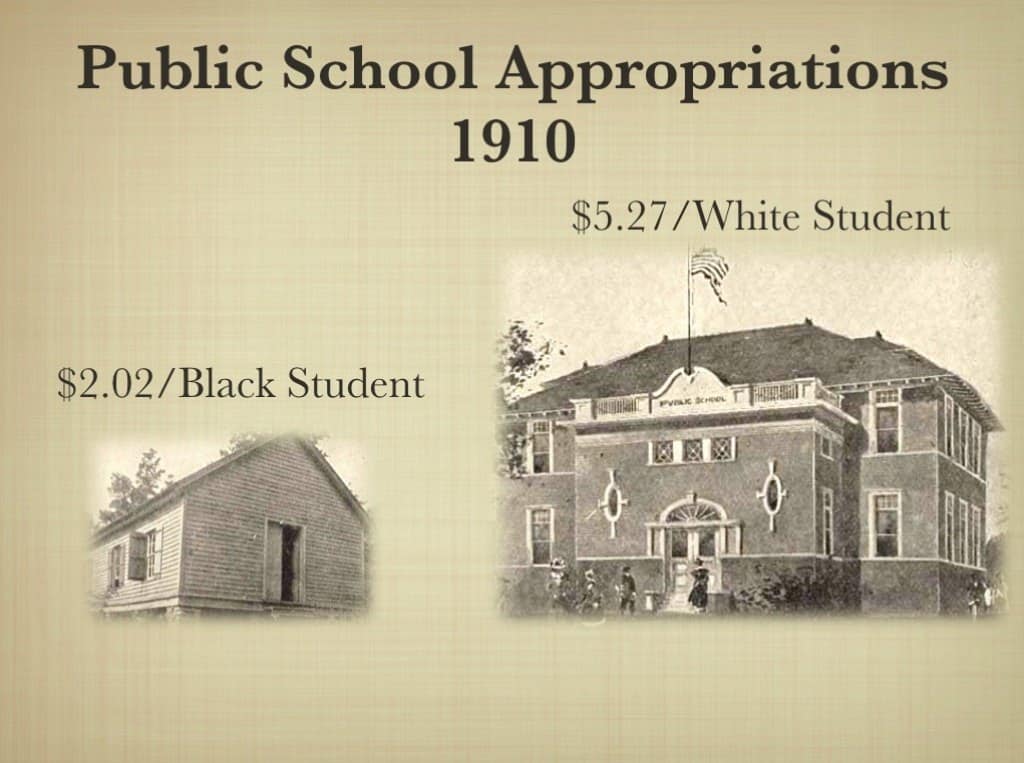

There are other intentional disparities.

Superintendent Joyner writes to superintendents to advise them on how to approach disparities in opportunity:

“The negro schools can be run for much less expense and should be. In most places it does not take more than one fourth as much to run the negro schools as it does to run the white schools for about the same number of children. The salaries paid teachers are very properly much smaller, the houses are cheaper, the number of teachers smaller …. If quietly managed, the negroes will give no trouble about it.”

This intentional strategy of inequity is evident in the public school appropriations in 1910 where the appropriation per White student is more than two and a half times that per Black student.

Historically, how has this been judged?

In 1936, our North Carolina Supreme Court expresses its opinion. It rules the literacy test to be constitutional and states further:

“It would not be amiss to say that this constitutional amendment providing for an educational test … brought light out of darkness as to education for all the people of the state. Religious, educational, and material uplift went forward by leaps and bounds.”

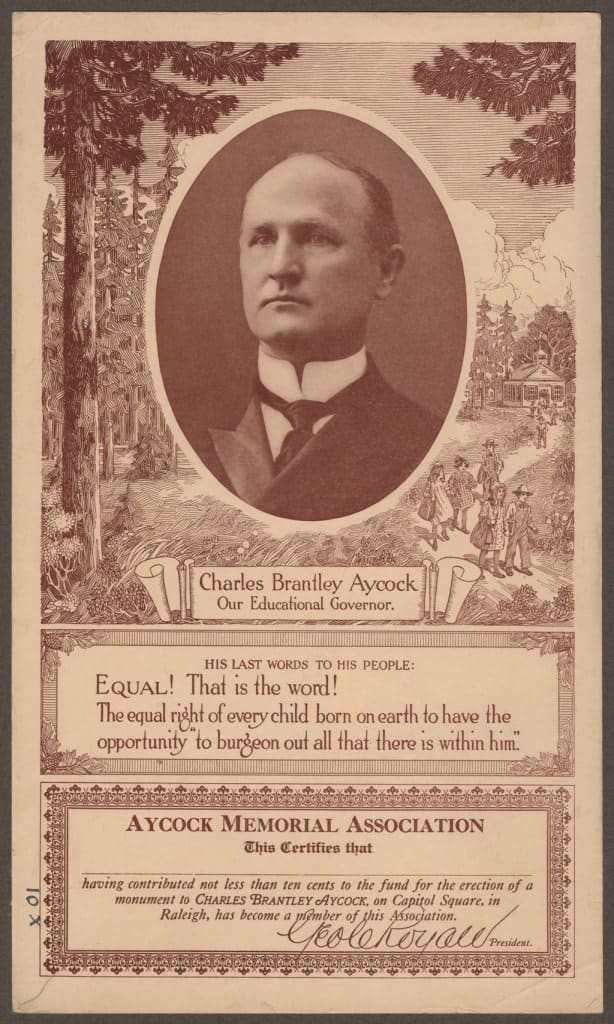

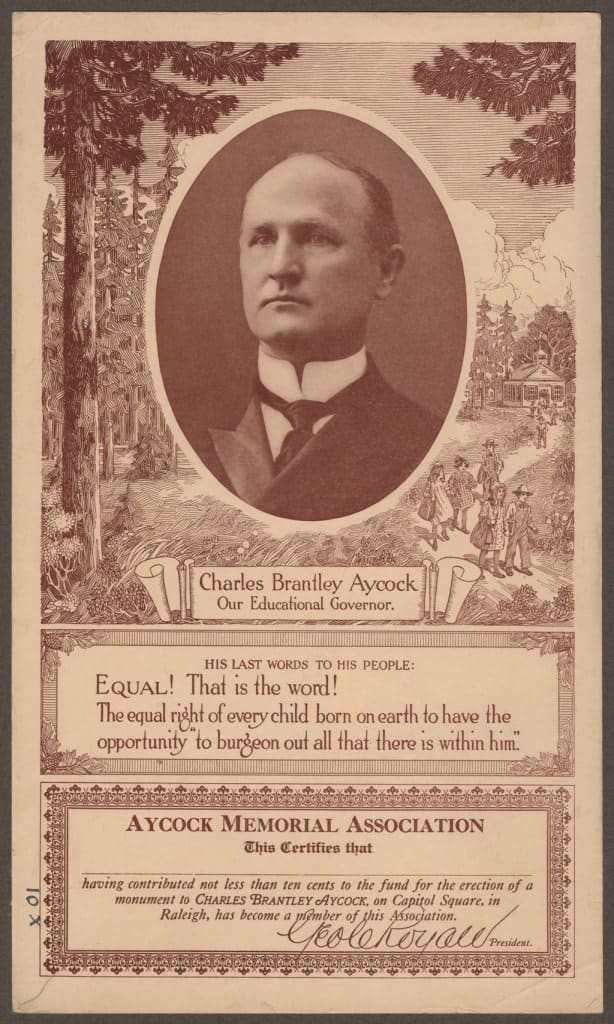

And Aycock? He is known as the first progressive governor.

The familiar saying is that a school was built in North Carolina for each day he was in office. And the words on this flyer are famous:

What do you think of now when you hear these words of Governor Aycock?

“Equal! That is the word! The equal right of every child born on earth to have the opportunity to burgeon out all that there is within him.”

And what about the literacy test? It is still in the constitution.

In 1901, voters pass the literacy test requirement by 59 percent to 41 percent. In 1970, voters reject repealing the literacy test by almost the same margin, 56 percent to 44 percent. It has no practical effect as federal law supersedes this but it continues on as a reminder of this dark history.

And what about the disparities in opportunity for a sound basic education? They persist as well.

Judge Manning will hear more about it on November 17 when he reviews test results and hears more about the State’s efforts in the on-going case on the constitutional right to a sound basic education. The Public School Forum is taking on educational opportunity as a major study focus this year.

While there is not space is this column to describe — I’ve already well exceeded what is known to be a good length for an online article — it is reassuring to know that in addition to this story, there are stories that show the dedication and purposefulness of North Carolinians to address inequities.

They include the heroes from the 1868 Constitutional Convention. They include the Jeannes teachers that rallied Black communities to apply for Rosenwald Schools. They include Dr. Dudley Flood and so many more.

What we learn from this story is the damage of intentional — and powerful — acts to create inequities.

There is no reason not to take the same level of intent and action to create equity.

A note about resources: To save space, individual citations have not been provided throughout the article. Many of the resources for this story are available from the State Archives, in the collections of J.Y. Joyner and Charles B. Aycock, along with other public documents such as the State Superintendent Annual Reports to the General Assembly.

To explore further, I welcome you to the website I maintain for Constitutional Tales, www.constitutionaltales.org. A part of the Constitutional Tales project has included, through the support of the School of Government and UNC libraries, making more resources digitized. You will find links to those resources on the website along with a detailed annotated bibliography.