Watauga County residents will soon have their first youth center.

Western Youth Network (WYN — pronounced “win”) has been championing the center since the organization’s founding in the 1980s. Headquartered in Boone, WYN partners with Appalachian youth and their families to provide them with quality out-of-school programs.

Self-described as providing services similar to Boys and Girls Clubs and Big Brother Big Sister agencies, WYN provides mentoring, after-school and summer camp programs, and community health initiatives to Alleghany, Ashe, Avery, Watauga, and Wilkes counties, a region also known as North Carolina’s High Country.

WYN’s longstanding commitment to their community means the organization has refined its service delivery, built trusted connections with High Country families, and delivered thousands of hours of trauma-informed care to the region’s young people. According to WYN’s 2024 annual report, programs served more than 400 students across the High Country last year.

WYN has also seen a 100% increase in demand for services year-over-year, and the organization has outgrown its physical spaces. The Watauga County youth center will change that, creating a new space for children, staff, and community members to gather and engage.

WYN’s history

WYN was founded under the name “Watauga Youth Network” in 1985 and began operating its first mentoring program, which served court-involved youth in Watauga County. The program, called “Friends,” operated on funding from former Gov. Jim Hunt’s one-on-one youth mentor grant program.

Since then, WYN’s programming has expanded to the entire High Country. The organization’s name evolved alongside its service region, changing to “Western Youth Network” in 2005.

The original goal of WYN’s programs, according to Executive Director Jennifer Warren, was to prevent young people from being taken out of their community and placed in the juvenile justice system. Instead of punishing young people for their actions, WYN’s programs are rooted in trauma-informed care. That includes acknowledging systemic factors that influence young people’s lives, equipping them with tools to navigate adversity, and enabling them to lead the lives that they want for themselves.

While WYN’s first program was targeted toward justice-involved youth, their broader mission today is to support children who may be overcoming adversity. Middle schoolers make up the majority of the youth served, and according to their website, WYN is the only after-school program for middle school students in Watauga County.

In practice, WYN’s approach to trauma-informed care aims to address adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), or potentially traumatic experiences that occur during childhood. These experiences include, for example, experiencing food insecurity or homelessness, witnessing violence, or growing up in a household with family members that experience mental health challenges. ACEs can have lasting effects on a child’s health and well-being, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Read more about ACEs

Warren said she first learned about ACEs in 2009, three years after stepping into her leadership role, and made it a priority to learn more about the research. WYN was one of the first organizations in the area to fully adopt ACE’s trauma-informed framework, a decision that she said has contributed to its leadership in the area as a child care organization.

“Once you learn about ACEs, it makes so much sense,” said Warren. “Of course they can’t think about math. Their thinking brains aren’t turned on because they’re living in survival mode.”

In other words, ACEs equipped Warren and her team with terminology and research to better understand the types of adversity their students experience and, in response, the kinds of support they need most from WYN staff and volunteers.

“We believe wholeheartedly that every child is a good child who might be having a hard time,” said Warren.

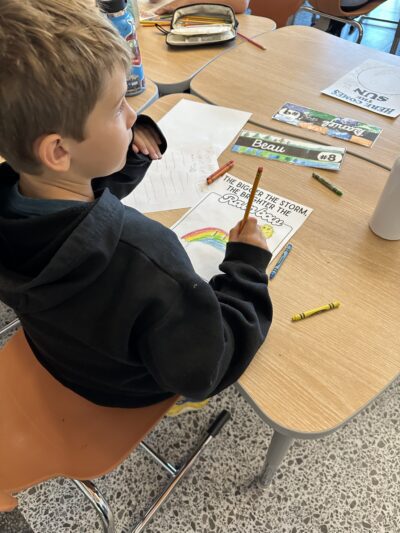

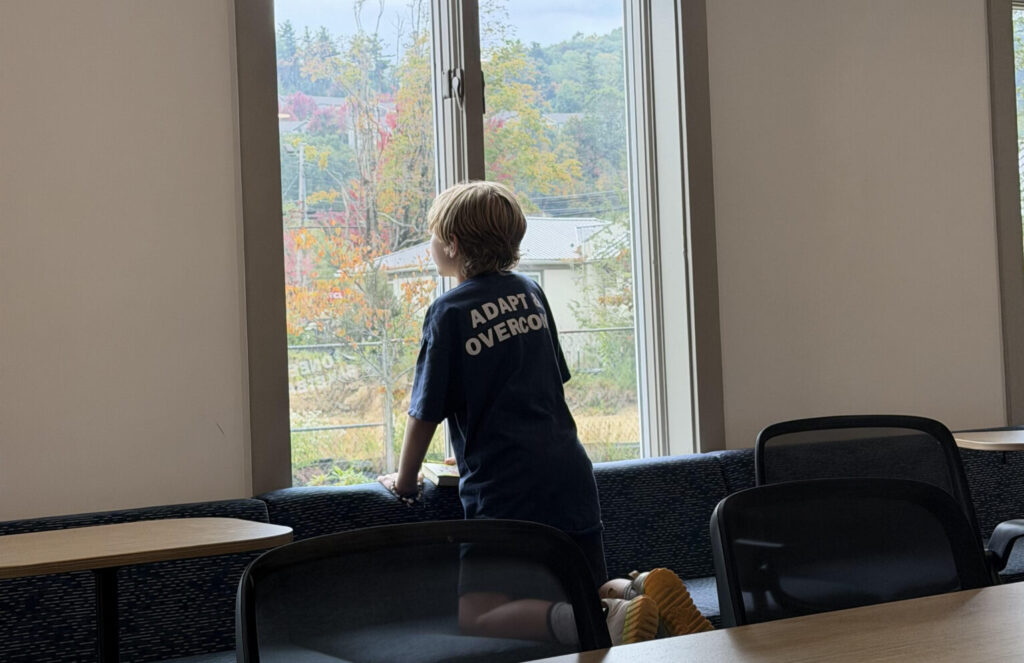

Building resiliency, a characteristic research shows is linked with overcoming ACEs, is at the core of WYN’s programs. During after-school programs and summer camps, for example, students interact with WYN staff that have been intentionally trained in child development and the concept of a resilient zone. This zone is a person’s window of tolerance for stress. To be outside the zone is to be dysregulated, and the distress a person feels when in this state explains unhealthy behaviors they might engage in to try to get back to a regulated state.

A main goal of WYN’s programs is to teach children how to return to their resilient zone and make choices that advance their well-being. One way WYN staff do this is by modeling and encouraging healthy behaviors.

“You can go find a new staff person and have a conversation with them. You can maybe take a drink of water. You can go take a breath of fresh air,” said Warren. “Describing us as an out-of-school-time program, or after-school program, sometimes doesn’t do it justice. It really is quasi-therapeutic.”

WYN’s mentoring program is another key part of WYN’s trauma-informed programming, as the presence of a trusting, caring adult is a strong predictor of a young person’s resiliency.

As of WYN’s 2024 annual report, 103 children were in the mentorship program. WYN’s mentors go through an extensive application and training process, including training in mental health first aid, ACEs, roleplaying scenarios that might arise during mentoring, and an hour-long interview with Angela McMann, WYN’s director of mentoring.

Having worked at WYN for over 20 years, McMann holds mentors to a high standard, asking herself: “‘Would I leave my kid with that person?’ And I say ‘yes’ for all of them, and I have been able to say that all along,” she said.

We believe wholeheartedly that every child is a good child who might be having a hard time.

— Jennifer Warren, WYN executive director

![]() Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

Sign up for the EdWeekly, a Friday roundup of the most important education news of the week.

WYN for the community

Adaptability and commitment to community has been WYN’s life blood for four decades. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, WYN continued to run its mentoring program in driveways. They continued after-school programming online and stayed in touch with their students, including checking in on their mental health.

“I’ve realized that we can take on most anything, because we aren’t structured in a way that doesn’t allow us to move about,” said Warren.

When Hurricane Helene damaged the region in September 2024, it also revealed how strong of a presence WYN is in their community. Because of existing networks, trust, and knowledge of the region’s mountainous geography, WYN leaders and mentors quickly mobilized resources to aid the community’s recovery. Avery County’s mentoring team, for example, provided stability to children out of school and pulled together resources for families after the storm, according to the 2024 annual report.

“They were a hub, because people know who we are,” said McMann.

Read more about Hurricane Helene recovery

As a child care provider, WYN plays a crucial role in sustaining the area’s workforce, and the hurricane exacerbated the region’s already-scarce supply of child care services. In light of this need, Warren said that when parents had to return to work before their children’s schools reopened, WYN quickly turned their after-school program into a day-long program.

Outside of disaster response, Warren added that WYN’s after-school care, available at low or no cost to families, helps working parents with school-age children remain in the workforce. During a visit to WYN’s Boone campus in May, Lt. Gov. Rachel Hunt acknowledged these efforts that operate at the nexus of education with workforce development.

The Boone Area Chamber of Commerce and its president, David Jackson, are also advocates for the region’s child care. Jackson commissioned a 2024 study on the state of child care in Watauga County. The report revealed that 300 people are kept out of the workforce due to insufficient child care options, and it notes WYN’s role as a part-time experiential child care program.

Watauga County’s first youth center

Damage from Hurricane Helene in 2024 also resulted in WYN moving out of the building it used for after-school programming in Watauga County since 1992.

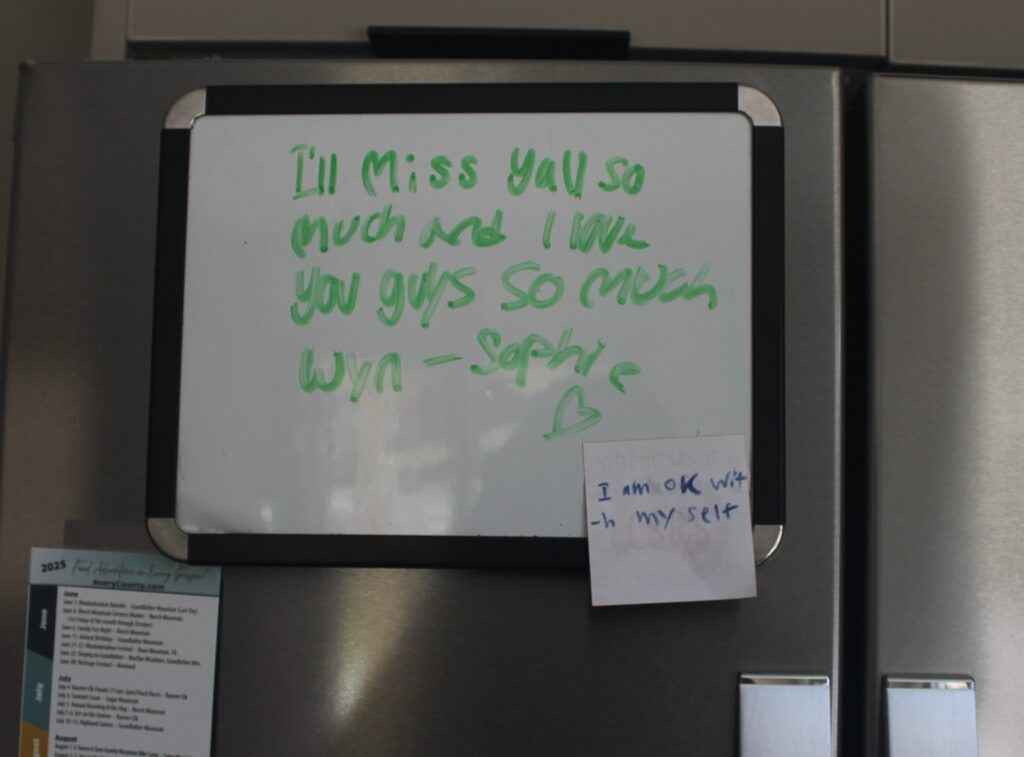

Since then, after-school programming has operated out of WYN’s administrative building, and students have been spending their afternoons alongside Warren, McMann, and other WYN administrative staff.

That will change in 2027, when WYN plans to open their new youth center in Watauga County. Since launching their capital campaign earlier this year, WYN has raised over half of their campaign goal. WYN broke ground on the project in May 2025, and as of October 2025, the campaign is $3 million from its goal.

The significance of the almost 20,000-square-foot building is far-reaching. Not only will it return students to their own space, but it will provide an accessible and enriching place for the WYN community to gather.

The 2024 Watauga County child care report highlights that the new center will provide programming for up to 150 students. Plans for the center include dedicated classrooms for after-school students, a teen center, multipurpose rooms for parent education courses, and a kitchen for nutrition education. Part of the campaign also includes hiring an on-site mental health counselor.

And, in a big step forward for WYN, the center will expand the nonprofit’s capacity to serve more students across different ages. Warren’s dream has been for WYN to provide services along a continuum of care, intervening when children are young and supporting them through high school graduation. According to Warren, the center will make that level of early intervention and continuity of care possible.

“With the power of that level of stability in your life, having this place that is a home away from home, and often people and staff members that you can count on from one year to next,” she said. “When you have that kind of consistency and that kind of third space in your life, it’s special and it’s meaningful.”

Warren and her team at WYN have big visions for the future of their work. That may include helping other rural counties replicate WYN’s work, an effort Warren said they have already begun in a few communities. After many years specializing in their work, Warren says she and her staff feel confident in the quality of their services and the impact they see it have on their community.

Recommended reading