When the EducationNC team took on the massive task of visiting all 58 community colleges in the state in about a week, my first stop was McDowell Technical Community College in Marion.

https://twitter.com/yasminbendaas/status/1034163382180560896?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1034163382180560896&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ednc.org%2F%3Fp%3D65784

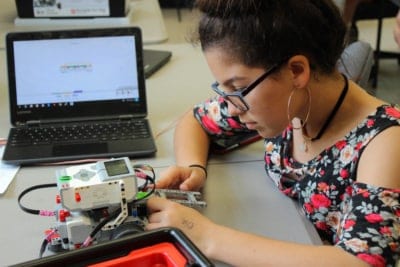

My tour began by hearing from the fire and rescue leaders and visiting the college’s new simulation lab, robots and all. (See my story on MTCC’s sim lab here.) To wrap my day, I sat down with President John Gossett and Vice President for Learning and Student Services Penny Cross to talk about significant issues like faculty retention, funding priorities, and student success. See our conversation below, edited for length and clarity.

Bendaas: What is the best kept secret on your campus?

Gossett: The first thing that comes to my mind is our people. As you visit other schools, you’ll see that we’re all different and we all do things differently, but we’re all remarkably the same and what differentiates is the service. I’m very, very proud of how our front line people interact with students, especially new students.

The educational bureaucracy is overwhelming — even to those of us who are in the industry — and for first generation college students who have no support at home in that the parents don’t know what they don’t know … They can’t guide because they’ve never been through that themselves. It’s a wonder that any first generation student gets through just the admissions process that we have now, cause I see it. Our student services is just around the corner, so I see it a lot. [They’re] so kind, so patient, especially with those new students.

We’ve got some programs that some people don’t. You’ve seen those this morning, and that’s wonderful and grants helped us get that. But our secret really is our folks.

Cross: All I would add is the caliber of our faculty, besides our staff. I think at times people are really surprised that we have the quality and caliber of faculty that we have here.

Gossett: I’ll tell you a story to go along with what we were just talking about. Last week … I get an email from a mom going through the — and I call it administrivia — it’s just the junk that you have to go through to apply, and the placement test, and the residency, and all of that. The money quote from this mom was they left student services frustrated, and her daughter said, “If I’m too dumb to get admitted, I’m definitely too dumb to be a student and pass a class.” Heartbreaking. Thankfully, our receptionist saw that these two were under stress, [and] called a faculty member who is an adviser.

The [email] said, “He offered my daughter a tissue. [He] was patient while she calmed down.” And all of that is counseling kind of work. That’s not advising kind of work. All of our folk, staff and faculty, just care about students. And it did my heart good to see that part of her letter … Now she’s enrolled, and she’s a student, too. The mom is.

Bendaas: How have you seen the make up of your student body change over the last five years?

Gossett: Younger, much younger. There’s still a market for people who graduated high school and went straight to work and need more education in order to get promoted. But our student body, specifically on campus, is made up of a lot of early college students. Adults, because they’ve got family and children and jobs, they’re more attracted to online classes. We don’t see them. They’re enrolled, they’re just not underfoot, as it were.

So I’ve seen a huge change in the age. When I first got this job, I talked to George Fouts. He’s been kind of one of those founding fathers in North Carolina Community Colleges. He’s worked here for 30, 40 years. He’s been vice president. He’s never been a sitting president, but he’s been an interim president, worked at the central office.

He said, “You know, I think we’re about done with serving adults.” And that really shook me. Because that’s who community colleges have been forever. When we were born in the ’60s, there was a huge demand for education for people who couldn’t go off to university, especially in rural North Carolina. Well, the community colleges have solved that for the most part. And anybody who wants higher ed has had access to higher ed.

His thesis was, “Maybe we need to reinvent ourselves.”

The whole drive back from Raleigh I thought about that and thought about that. That’s not who we are. That’s not our history. But he’s right. Our industry is changing drastically.

Bendaas: What are your top funding priorities over the next three to five years, and how do you see these priorities play a role in student success?

Gossett: To me the biggest game changer in our funding is equating our credit and non-credit offerings. More and more industry are telling us, “Your two-year degree or one-year diploma is nice and all, but what can those graduates do? Prove to me that they can weld or run a CNC machine.” Often times that is tested by and verified through third-party credentials. Well, if that’s what industry is going to reward, then that’s what I want to teach.

Do students really need to go through a 16-week, 4-credit class that meets three times a week, or can they learn that skill in maybe … two months in a much more condensed, quicker fashion, proved by that third-party credential? So if the General Assembly will equate those two — now I don’t have to force students into one area because it pays back more. I can put students where they want to be, where they need to be to get the job. I mean that’s why we all went to school, was to get a job…

Our society is impatient. We don’t want to wait. We want things when we want them, and education’s no different.

Cross: For me a priority — and I think for Dr. Gossett as well —we’re trying to figure out how to serve our students better, so we’re focusing on and we’re getting ready to start planning a quality enhancement plan (QEP) … Within that QEP we’re exploring different options, and student recruitment and retention is a priority. So we’re looking at student success measures, and if funding can help, that would be what we’d be interested in doing.

Bendaas: Could you describe what your faculty recruitment and retention strategies look like? How would you rate the success of your strategies to date? Who are your primary competitors for faculty recruitment and retention?

Cross: In this area, we don’t have a lot of competition for our faculty. When people come, they tend to stay. We don’t have a lot of turnover.

Gossett: We don’t have a lot of turnover, which is good. They’re voting with their feet, and that means they’re staying here. They like it here. We don’t ask an awful lot of our faculty to do things outside the classroom. I’ve been involved with some leadership teams where the president and vice president wanted to kind of meddle in how teachers teach. We don’t do that. Our faculty are quite tenured. They’re seasoned. They’ve been doing it awhile, and everybody has a different style, everybody has a different strategy — as long as students are learning, I don’t care if they stand on their head to make it happen.

We give a little more support to our newer faculty, of course. They need it. And they pretty quickly team up with someone in their department as a mentor to help them through that first year. Retention is just not an issue that I have to deal with with faculty.

Cross: They pour themselves into their students.

They’re really invested in their students’ success.

So I guess our strategy is we try to make the work place an enjoyable place to be. We have expectations: do your job, let’s look at the outcomes. Is student success going on? And we find that, by and large, we have really good student success stories.

Bendaas: Other than your people, what strengths do you believe your institution brings to the table? And how would you describe challenges facing your institution?

Gossett: We are very well-connected with our K-12 brothers and sisters. I think we are well-connected with our business and industry. So that continuum of kindergarten through high school through us to get to the world of work in McDowell County is probably as strong as it’s ever been. I’ve only been here seven years, and I’ve heard stories from the old days where that wasn’t always the case.

We have a manufacturing pipeline committee … It really started when one guy stood up and was complaining about the workforce and kind of as an off-handed comment said, “Well, maybe we just need to grow our own.” Basically talking about engineers. I was sitting next to the superintendent of schools, and we kind of poked each other.

The manufacturing class was a result of that pipeline committee. An awful lot of what we do in our technical and vocational programs is a result of the things that they tell us. The relationship has been built over seven years that we don’t just have advisory committees and they don’t just tell us what they think we want to hear. They tell us the truth … And I think that is something that not a lot of schools have. It is huge for us in our ability to meet the needs of our manufacturers. We’ve toyed with the idea of a similar kind of committee in health care.

Bendaas: And the challenges?

Gossett: It’s easy to say, “Well, funding’s a problem.” I don’t know that that’s the core problem that community colleges have.

Ken Boham, who’s recently retired — he was a president at Caldwell, he used to say it all the time:

“Everybody wants to dance with us. Nobody wants to take us home.”

And that’s true. When we hear the General Assembly talk about community colleges, they brag on us a lot, but we’re getting about seven or eight cents on every educational dollar that the state spends. So, the biggest challenge: respect, might be a word.

Bendaas: Are you talking about respect across the spectrum? Or are you talking about legislative respect?

Gossett: I would say across the spectrum … I think, and I don’t have evidence of this and nobody has proven this to me, but I think our counselors in K-12 push kids to four-year schools because that’s what their experience was so they think that’s the experience. And it doesn’t have to be. You don’t have to go off to a four-year school to finish at a four-year school. You don’t have to go to a flagship institution in order to make a ton of money and be happy. So it’s not just the General Assembly, it’s our society.

I think that’s changing. I’m seeing more people talk about community colleges as an option, more than I’ve ever had before. But we’ve got a long way to go.

Bendaas: Any final thoughts?

Gossett: I didn’t know what a community college was until I applied for a teaching job. Once I started teaching, it didn’t take long to realize that I can do more good for more people at a small rural community college than I can anywhere else. At that point, I thought well I’ll get my feet wet teaching and then I’ll go to a university where I can be a real big shot.

But our students tend to stay here. They’re the people who are going to be our county commissioners, our school board members. They’re going to own businesses. They’re going to work in our manufacturing and be supervisors and leaders. They’re going to work in our hospitals and take care of us when we get old.

Our students, when I see them out in the world, and see that they’ve gotten a job and they’ve created a career, that’s really rewarding. And I love that about what we do … We’re making a difference. We’re making a real difference, and that’s why I do what we do. I’m proud of it. I’m very proud of it.

https://twitter.com/yasminbendaas/status/1034178911461101573

The “blitz” followed an investment from the John M. Belk Endowment allowing us to delve into community college news and coincided with the launch of our community college-centered initiative, Awake58. Read more of our community college articles and keep up with us on Twitter @Awake58NC.

Recommended reading