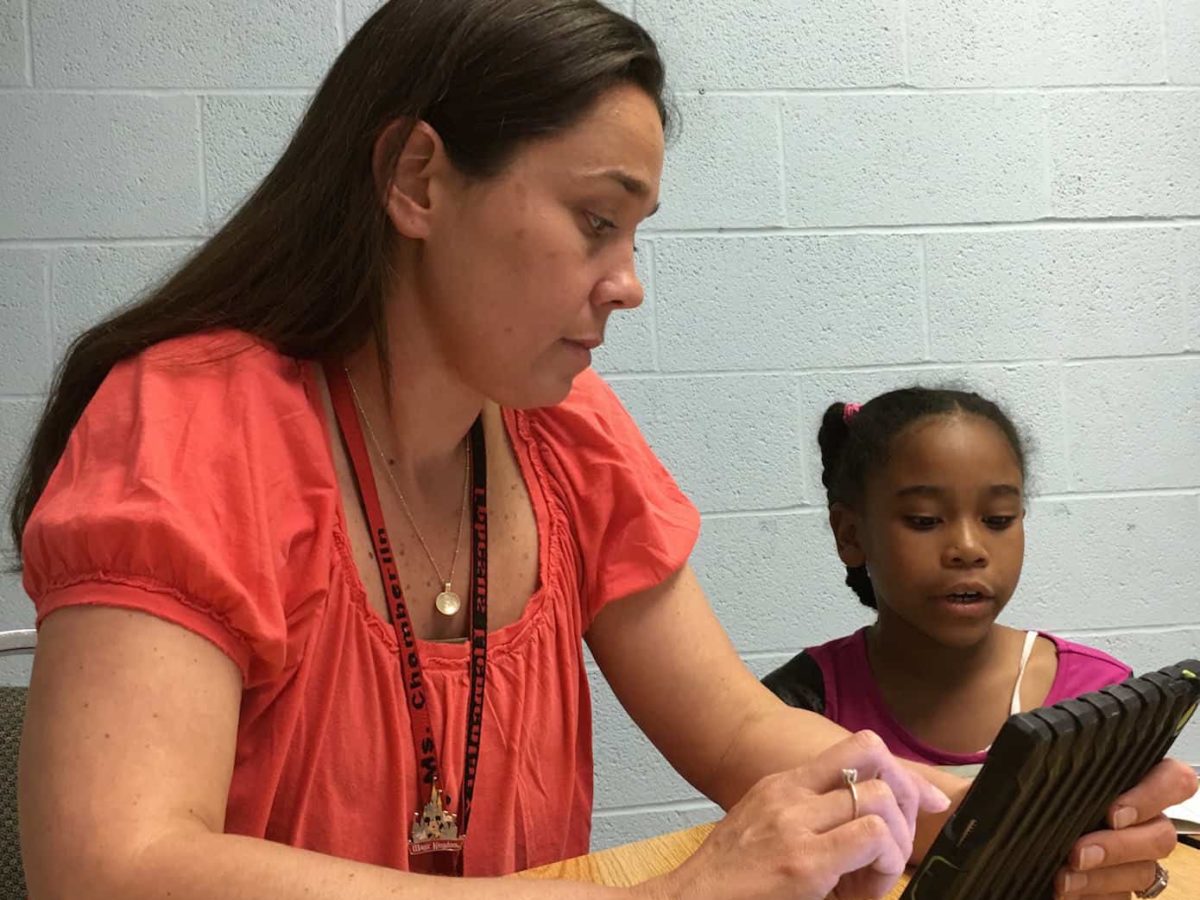

Throughout the month of May, kindergarten through third-grade teachers across the state will administer end-of-year reading assessments, one-on-one, to students using the state mandated digital system known as mCLASS Reading 3D. This is the third time students will be assessed on mCLASS–it is administered at the beginning and middle of the year as well. One component, the Text Reading and Comprehension (TRC) measure, uses two tried and true measures of reading development and one measure of grade level standards to attempt to identify the instructional reading level of each student.

First, a running record is used to assess reading accuracy. Second, oral comprehension questions are used to determine how well a student can demonstrate comprehension of a text orally. Third, for text levels F and above, two written responses about a text are used to determine if two grade level reading standards have been mastered. This type of data is familiar to elementary teachers, but in the past, teachers collected, interpreted, and placed this data in the larger context of everything they knew about their students in order to inform instruction. Now, it is ultimately an algorithm on a device that makes the final analysis. We find this algorithm to be limited in its usefulness as an instructional tool and lack confidence in the assessment’s ability to accurately assess reading levels based on the following concerns:

- mCLASS rarely provides an instructional reading level, one where the text is neither too easy nor too hard, the “sweet spot” for reading instruction.

- The written comprehension component often assesses standards before they have been taught and uses an unacceptable sample size to determine proficiency.

- The decision to also use mClass as a measure of teacher effectiveness has resulted in the prioritization of analysis by algorithm over teacher judgment and expertise.

Difficulties with the TRC

The TRC is described as a tool to help educators select texts for students that are “neither frustratingly difficult nor ineffectively easy.” Finding the instructional level is critical to reading growth. As a second-grade teacher and a literacy coach, we have administered well over 400 TRC assessments to students using mCLASS Reading 3D, but in our experience, mCLASS TRC data rarely provides instructional reading levels. In one classroom this year 52 middle of the year TRC assessments were administered by a classroom teacher to 21 students. In only two cases was the mCLASS TRC assessment able to identify an instructional reading level for the student. For all other students in the class, when consecutive reading levels were assessed, the system identified all of them as either too easy (independent) or too difficult (frustrational). We see this trend repeated from year to year and across classrooms. This does not mean that children do not have instructional reading levels, only that, in its current form, mCLASS can rarely identify them.

Most classroom teachers will tell you that the written comprehension section of the TRC is what causes a student to score at the frustrational level. After reading with 99 percent accuracy and answering five out of five oral comprehension questions correctly, a student who misses either of the two written comprehension questions is scored as non-proficient and the book level tested is considered frustrational. This happens because the comprehension questions are designed to measure specific reading standards that may or may not have been taught to the student at the time s/he reads the mCLASS text. Students’ reading development follows a specific trajectory, but not necessarily the same path as the scope and sequence a teacher or district uses to pace out standards. But Common Core State Standards address this discrepancy when they say, “The K-12 standards…define what students should understand and be able to do by the end of each grade.”1 At the beginning and middle of the year, when none or only a portion of the reading standards have been taught to mastery, the written response portion of the TRC still tests each student on the standards, and each time a student fails to demonstrate proficiency, their reading level goes lower and lower. We agree that literacy instruction should explicitly show the interconnectedness of reading and writing; however, we find that the written comprehension scores on the TRC can sometimes “level” a student two or more levels away from where the student can effectively read and comprehend.

The TRC’s impact on students and instruction

To be clear, students are regularly not passing a TRC level because they miss one question on a standard they are not expected to master until the end of the year. The assessment’s algorithm for proficiency is clunky and lacks statistical merit. No other assessment administered to children in the state of North Carolina, that we know of, uses a single question to determine proficiency on a standard. Classroom teachers are quite capable of interpreting the raw data with greater finesse and sophistication. When teachers are given less interpretive power, the clunkiness of the algorithm can have significant negative effects on reading instruction in the classroom. When a student receives an inaccurate and below grade level score on the TRC, it triggers a cascade of reading interventions and progress monitoring assessments, many of which may never have been necessary. It also means that children may be taught at lower levels, leading to lower engagement and less growth. Because of the weighty impact written comprehension questions have on TRC scores, teachers feel pressure to shift reading instruction from high quality thinking and responses to practicing formulaic answers to TRC-like question stems. The best way to improve the quality of writing is to do a lot of it — across all subject areas. If we teach writing throughout the school day and focus on quality feedback, we expose students to higher order thinking and processing through frequent and regular practice.

The metamorphosis of the TRC: Formative to summative

The climate of accountability has led legislative and educational leaders to expand the reach and role of the TRC. It is no longer treated as the formative assessment it was designed to be. The TRC has morphed into a summative assessment and a teacher evaluation tool. Schools compare fall TRC reading levels with spring TRC reading levels to determine the reading growth students make in a given school year. Also, TRC levels currently serve as the sole measure to calculate a kindergarten, first, or second-grade teacher’s value-added score in the NC Educator Effectiveness System. To guarantee objectivity in the evaluation of teacher performance, the judgment of the digital device is prioritized over the classroom teacher’s. Devaluing teacher judgment in the formative assessment process is having a negative impact on early reading instruction in North Carolina. Plus, using mCLASS to evaluate teacher effectiveness, a job it was not designed to do, is unfair to teachers and demonstrates an inappropriate and naive use of mCLASS data.

How the TRC can be used effectively

TRC has the potential to be a useful instructional tool. Teachers need to know a child’s reading behaviors, and the mCLASS digital platform collects, displays, and shares reading behavior data well. But teachers also need to be able to interpret mCLASS data in light of all that they know about each particular student. TRC data reflects one reading of one book on one day. Teachers read many books with students across many days. One simple way to restore teacher judgment and strengthen the usefulness of the TRC is to separate the standards-based written comprehension scores from the accuracy and oral comprehension scores. Teachers can then use the written work as one indicator of a student’s progress toward the standards without having it confuse the analysis of a student’s reading growth and development. Ultimately, the power to interpret the data in ways that improve classroom instruction should belong to teachers.

We recommend the following

For teachers

- Always aim to instruct students at the highest level they are able to read and comprehend. If a student needs support in writing, consider carefully if reading lower level texts will improve their writing skills.

- Resist the urge to practice writing about reading using only TRC-like question stems. If students need to become better writers, give them plenty of opportunities to write across the instructional day.

For administrators

- Do not require teachers to always match instruction to the text level reported by mClass. Remember that the mClass TRC is often unable to identify instructional reading levels for students.

- Support teachers to use a variety of information and sources including mClass to guide reading instruction. Offer teacher-designed and teacher-led PD to assist teachers with identifying the instructional reading level of students using both mClass and other evidence.

For policy makers

- Consider the effects of using the TRC as both a formative and summative assessment as well as a teacher evaluation tool.

- Separate reading and writing scores so that teachers can interpret both pieces of information separately and make more nuanced assessments of students’ needs.