Every teacher knows the feeling of getting an unexpected phone call in the middle of the morning at school. Students gather around you as you discover something deeply personal has happened. On May 18 of this year, I received that phone call. My last grandparent passed away while I was teaching a class.

On my way home from work, my father asked the question that brought me to tears: “What was your favorite memory of grandma?” What I remember most as a child were the stories my grandmother told as I went to bed — stories of our family and the village we had come from in Austria.

My favorite story was about her first day of kindergarten in South Bend, Indiana. My grandmother’s parents were immigrants who came to America for each other, for love, and for family. They lived and worked in an immigrant community of Slavic people in South Bend. Culturally isolated, my grandmother never learned English.

For me, the first day of kindergarten consisted of laying in an antique bathtub in Mrs. Davis’ room with books, walls of letters, and sharing circles. For my grandmother, it was one of fear, tears, and tissues. She couldn’t speak English. She couldn’t read a word. Every day of kindergarten she returned with her tissues in hand.

My story of literacy is the story of my family.

Looking back, as I closed out the end of my student teaching as a high school English III teacher, I was uncomfortably aware of the need for literacy to be everywhere in a student’s life. Just like me, some of my students’ families stories of literacy were crouched in isolation, fear, and shame.

My hope as I began my teaching career the following fall was to transport students to antique bathtubs, fearless dreams, and lives drenched in words.

Little free libraries

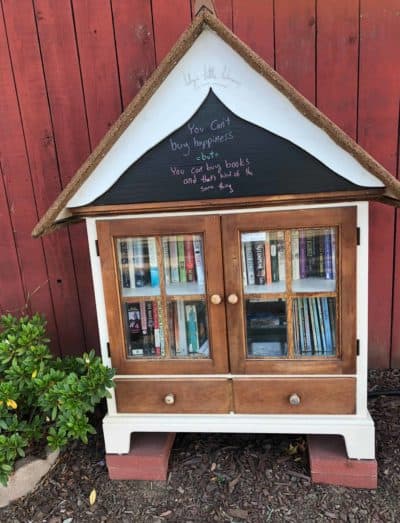

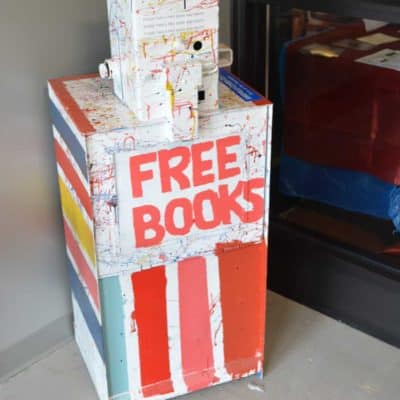

While going on summer walks with friends before my first full-time year of teaching, I came across my first little free library in the Cameron Park neighborhood on the fringes of N.C. State’s campus. I thought to myself: “What a ‘novel’ idea for communities to recycle used books in a way to integrate literacy everywhere in the lives of all others that walked by.”

As I have traveled the state in my summers with EducationNC as an executive fellow, not only have I seen little libraries in neighborhoods and communities, but they have moved onto the grounds of schools and community centers.

Wanting to learn more about this trend and where they came from, I discovered Little Free Library, a nonprofit “that inspires a love of reading, builds community, and sparks creativity by fostering neighborhood book exchanges around the world.” According to the organization, through these little free libraries, millions of books yearly have been traded in communities across the world.

On their website, you can map where libraries are around you, and you can register ones already in existence. You can even purchase materials to build your own. See the map below of Little Free Libraries registered in North Carolina.

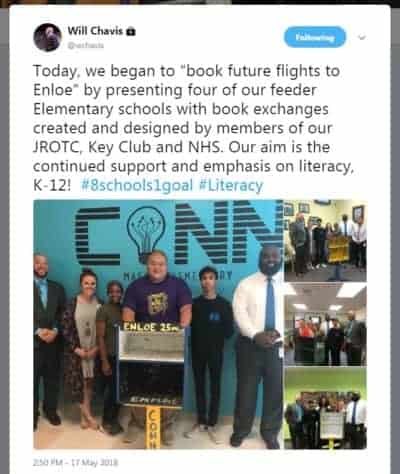

This past school year, Enloe Magnet High School’s Junior ROTC program, Key Club, and NHS began a partnership with their elementary schools by building mini libraries and supplying books through book exchanges on each campus.

21st Century Community Learning Centers

To promote engaged literacy everywhere, the Every Student Succeeds Act enacted by the U.S. Congress appropriated money for the U.S. Department of Education to fund programs known as 21st Century Community Learning Centers.

According to the U.S. Department of Education, a 21st CCLC “supports the creation of community learning centers that provide academic enrichment opportunities during non-school hours for children, particularly students who attend high-poverty and low-performing schools. The program helps students meet state and local student standards in core academic subjects, such as reading and math; offers students a broad array of enrichment activities that can complement their regular academic programs; and offers literacy and other educational services to the families of participating children.”

Awards for the programs and grants go to State Education Agencies who then sub-grant to Local Education Agencies and other nonprofit organizations. Organizations can access information about resources, external organization profiles, and grant cycles in North Carolina at 21st Century Community Learning Centers.

You for Youth

If your school or organization does not have access to these grants, the U.S. Department of Education created a free online professional learning and technical assistance center for coordinators, directors, and practitioners called You for Youth.

Free of charge, any educator, instructional coach, administrator, or community leader can access courses on literacy, implementation strategies, coaching support, and tools to take into any classroom or community center across the state.

One such module in the training program specifically addresses Literacy Everywhere and the six key strategies ensuring the implementation of literacy for in-school programs and out-of-school-programs. In addition to these six strategies, the Y4Y modules provide resources to help schools and community programs assess whether or not they are targeting student literacy skills. The strategies are as follows:

- Create an environment that facilitates literacy acquisition.

- Expose children to a wide variety of high-interest reading and writing materials.

- Use project-based learning to facilitate authentic connections between learning and life.

- Incorporate digital technology and other 21st-century learning tools.

- Involve families in meaningful learning experiences.

- Empower students through learning, and celebrate success.

Without any cost or grant writing, community program directors and educators can use these resources to start transforming our schools, community programs, and state into literacy havens. Within the walls of the school I teach, and the roads stretching across North Carolina, I have seen each of these strategies in action.

Create an environment that facilitates literacy acquisition

The training module asks programs to “assess the H.E.A.T. of your literacy environment. How does your program foster literacy with: Higher order thinking, like practice comprehension and analysis? Engaged learning, such as literacy activities students enjoy?”

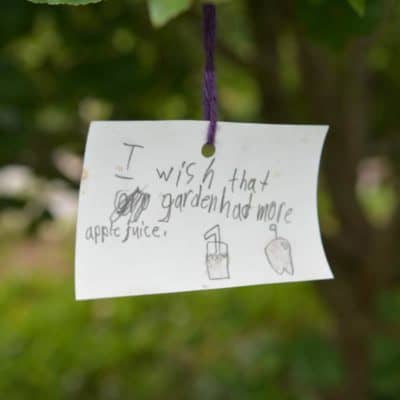

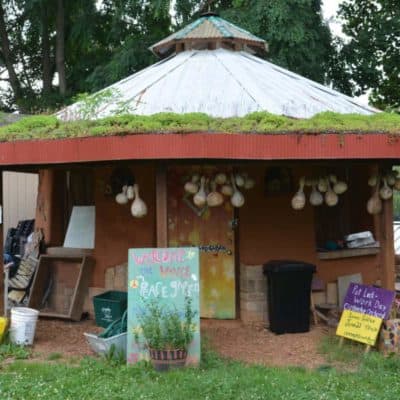

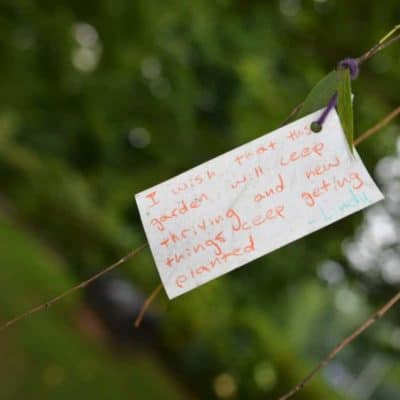

On July 13, EducationNC visited Asheville’s Vance Elementary Peace Garden supported by Bountiful Cities and found multiple levels of engaged literacy instruction that pull students into a space of food, science, and gardening, coupled with authentic writing opportunities around hopes and dreams. It was evident that students enjoyed the literacy activities, including writing in the outdoors. Executive Director Darcel Eddins explained students learn to not “yuck other people’s yum.”

Expose children to a wide variety of high-interest reading and writing materials

On the same trip to Asheville with Bountiful Cities, we came across free libraries at both the Vance Elementary Peace Garden and the Hall Fletcher FEAST Garden. The Hall Fletcher FEAST Garden combines cooking, gardening, nutrition and aquaponic instructional units. Materials inside and outside the classroom included every type of literature — fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and also multi-lingual materials.

Use project-based learning to facilitate authentic connections between learning and life

The Y4Y guidelines around project-based learning seek to know: “How does your program foster literacy with service learning or real-world projects — e.g., organize a fund-raiser to benefit a charity, create a documentary related to a community issue?”

Not only does PBL take place in the classroom, but for 14 years, the students of Enloe Magnet High School have run a program known as Enloe Charity Ball which raises money around systemic social issues through writing, multimedia, and grassroots campaigns. The program has raised almost a million dollars for the local nonprofit community and last year raised $180,000 for the Raleigh-Wake Partnership to End and Prevent Homelessness. This year, the students have a goal of $200,000 for the new beneficiary.

Incorporate digital technology and other 21st-century learning tools

Another stop this summer with EducationNC was to the Arthur R. Edington Education & Career Center, a gathering place for the Southside neighborhood, one of the historically black communities in Asheville. Housed there is the Asheville Writers in the Schools and Community, which produces an online bilingual literary art, documentary film, and cultural magazine led completely by a “squad” of black and Latinx students, called Word on the Street/La Voz de los Jovenes.

Involve families in meaningful learning experiences

Not only does the Edington Center engage students, it also finds ways to involve family members in meaningful literacy learning experiences around cooking and eating in its very own Southside Kitchen, while also providing information on voting, and — oh yeah — another free little library.

Empower students through learning, and celebrate success

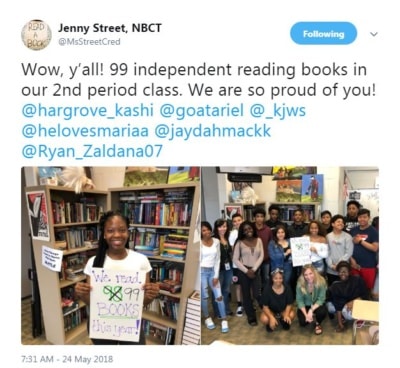

At Enloe Magnet High School, two colleagues of mine, Jenny Street and Kelley Schroeder, run a dual English I course with an additional block of Academic Reading that was written by Wake County literacy coaches and educators focusing on voice and choice around student reading engagement. This course is built on the celebration of lifelong literacy acquisition and being power-literate citizens.

Back to Edgecombe County

This month we are traveling back to Edgecombe County to install a Little Free Library for a mobile community of students that attend North Edgecombe High School, Phillips Middle School, and Coker-Wimberly Elementary School to grant their wish of having books about superheroes and chapter books.

From the first time I saw a little library after graduating college to today, I have made it my continued mission as an educator to encourage literacy everywhere and to allow families to harness their own story of literacy.

Recommended reading