Some seventh-grade students in Martin and Pitt counties have found even the tiniest of creatures can become addicted to sugar and caffeine – and energy drinks can be lethal.

That’s the outcome of the first of several studies with flatworms and the pharmacology of addiction funded through a four-year, $1.012 million grant from the National Institute of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse to researchers at East Carolina University and Temple University.

Dr. Rhea Miles and Dr. Scott Rawls received the funds to develop a sixth-to-12th-grade curriculum using planarians, or flatworms, that display the pre-clinical effects of addictive substances such as nicotine and alcohol. Miles is associate professor of science education in the Department of Mathematics, Science and Instructional Technology Education in the ECU College of Education. Rawls is an ECU alumnus and associate professor in the Department of Pharmacology and the Center for Substance Abuse Research at Temple University School of Medicine.

The researchers worked with two middle schools in Martin County and six middle schools in Pitt County on the Science Education Against Drug Abuse Partnership pilot program.

The hands-on curriculum exposes students to research, creates awareness about biomedical science careers, and teaches them about the science of drug addiction and the adverse effects of abused substances.

“They had not considered that caffeine and sugar could be a drug,” said Tonya Little, assistant principal at Riverside Middle School in Williamston and STEM Coordinator for the Martin County Schools. “They were really able to see the connections to their life.”

“I learned just because they (worms) don’t have what we have (arms or legs), they still act like we do,” said T’san Griffin, a Riverside Middle School student. “And it has taught me patience.”

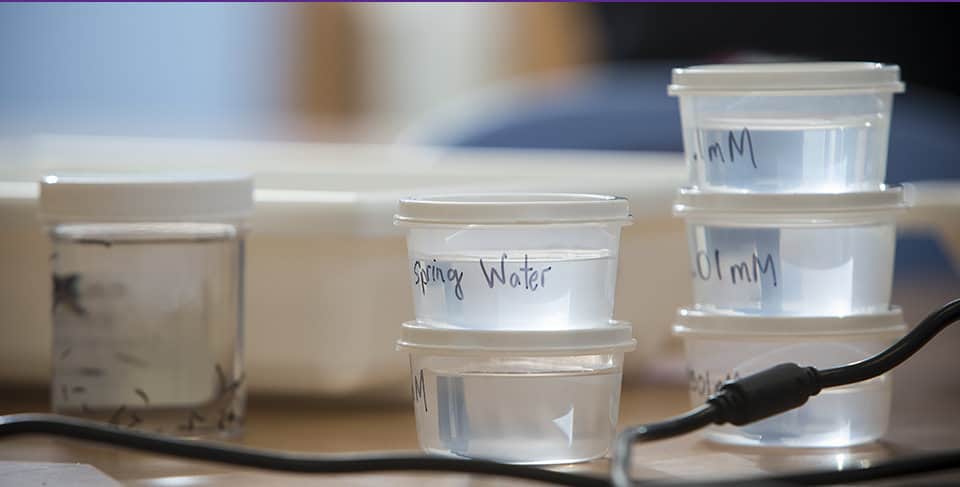

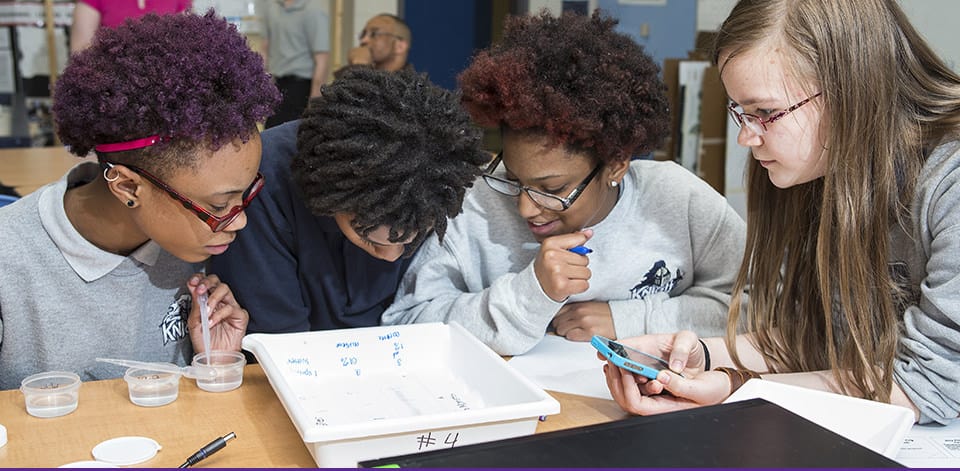

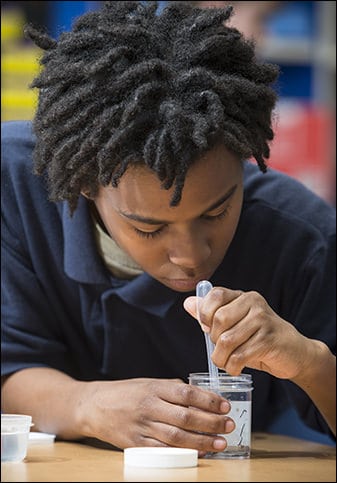

In one experiment, students placed flatworms into photo developing trays containing different concentrations of sugar and caffeine.

“You can’t tell a worm to go straight,” Little said. “The purpose of the developing tray was to give them a lane.”

Students used the stopwatches on their phones to time how long it took the flatworms to travel five centimeters. They discussed how the different concentrations of caffeine or sugar affected the motility of the worms. The students uploaded a video of the worms’ movement to a computer program to calculate the average velocity. If it takes a worm longer than five minutes to travel five centimeters, it is probably having seizures and will die if it is not detoxed, the students said.

Seventh-grader Sara Beach said she now tries to avoid sugar and caffeine. Most of the students said they’ve become more aware of food ingredients as a result of participating in the study.

“I drink more water,” Ashaunti Hyman said.

In another experiment, students put the worms in solutions containing energy drinks – beverages that contain large amounts of caffeine or other stimulants. Caffeine can cause nervousness, restlessness, or insomnia in some people. It can trigger seizures or abnormal heart rhythms at high amounts. An energy drink can have 75 to more than 200 milligrams of caffeine per 8-ounce serving compared to a typical soft drink with 30 to 60 milligrams.

The worms wouldn’t swim until the solution of energy drink was one percent or less, students said. “Some of them didn’t survive.”

Students learned that if you take too much of a drug, it can cause illness, serious complications such as heart attacks or possibly death.

“I think this program resonates with some students who may not listen to ‘just say no,’ ” Little said. “It’s more impactful than just ‘don’t do drugs’ or ‘this is your brain on drugs.’ ”

The data was calculated and plotted on graphs and each four-student team created a presentation on their results. Students presented their findings at a conference this month and will make another presentation to 4-H next month.

Little, who is pursuing a doctorate in educational leadership at ECU, hopes the program’s success will mean it will eventually be included in the regular middle school curriculum.

Two other STEM teachers at the school are Franklin Scott Jr., who teaches robotics and eighth-grade math, and Sarah Delph, who teaches eighth-grade science. Both are ECU alumni.

“A majority of students don’t get a lot of opportunities to do hands-on (learning) anymore,” Scott said. “Any opportunity to do that, to see, touch, and feel, is appreciated.”

Delph said students are motivated, more focused, and learn to work cooperatively as a result of the program.

ECU has started recruiting high and middle schools in several North Carolina counties to participate in the program for the next school year. Temple University has public school teacher cohorts in Virginia and Pennsylvania.