Editor’s note: This article is part of EdNC’s playbook on Hurricane Helene. Other articles in the playbook are available here.

As global humanitarian aid organization Save the Children responded to Hurricane Katrina in 2005, staff noticed a particular gap in awareness and support: young children and the programs that serve them.

“The child care world is often, unfortunately, just overlooked when it comes to disaster response,” said Victoria Rooks, the organization’s former lead associate of psychosocial support. For the last two decades, the nonprofit has focused on filling that gap.

When Hurricane Helene hit western North Carolina in September 2024, 148 licensed child care centers and homes with more than 5,000 enrolled children were impacted, according to an August 2025 state presentation.

A particularly fragile sector faced a particularly unexpected storm.

“The warnings look different and the response looked different because there wasn’t that community memory of what hurricanes can look like,” said Rooks, who has worked on responses to 14 natural disasters.

Just two months after the storm, 80% of licensed child care programs were reopened, said Laura Hewitt, Child Care and Development Fund coordinator at the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE) during the August presentation. Only two programs remained closed due to the storm as of December 2025, according to DHHS.

In the immediate aftermath of the storm and the months since, educators, administrators, support agencies, and state-level leaders evolved their approaches as the needs of children and families changed, learning how to provide support, coordinate, and find creative solutions. Advocates have worked to ensure early childhood programs are included in state and federal responses, while also planning for better recovery mechanisms for future emergencies.

Child care leaders interviewed by EdNC also noticed gaps in knowledge and preparedness, inefficiencies in communication, and at times, burdensome or delayed relief options.

Related reads

Rooks said infusing lessons from Hurricane Helene in future plans will be paramount, “knowing that more disasters are happening — and the areas that are impacted are not necessarily the same as the areas that have been impacted in the past.”

“Even if you don’t think this is something that you need to have a plan for,” she said, “having a plan anyway and doing it before something happens — your plan will be better and more supported, and then the kids that you work with and your employees and your teams will be better able to weather the storm.”

Disaster preparedness

At the program, regional, and state levels, leaders said child care emergency preparedness plans could have been better known and utilized.

Child care directors and owners should think intentionally and realistically about their required Emergency Preparedness and Response (EPR) Plans, local providers said. Local leaders said early childhood support organizations like Smart Start partnerships and Child Care Resource and Referral (CCR&R) agencies should also consider creating their own plans. And at the state level, advocates are looking to infuse DCDEE’s disaster plan with lessons from their Helene experiences.

One individual from each licensed child care program must complete emergency preparedness and response training under state rules. Each program is then required to create an EPR Plan and to review the plan with new staff at orientation and with every staff member once a year.

The plans include lists of contact information for children and staff, evacuation and transportation plans, relocation and reunification processes, as well as a Ready to Go File that contains important information in case of evacuation.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Helene, some of those plans came in handy, said Jennifer Simpson, executive director of Blue Ridge Partnership for Children, the Smart Start affiliate that supports child care programs in Yancey, Avery, and Mitchell counties. Yet reviewing plans once a year and going through a single training does not prepare you for the chaos of natural disaster, Simpson said.

“It just caught us off guard completely,” she said, adding that her organization is rethinking its emergency preparedness strategies for the future. “It suddenly has a realistic application.”

The NC Child Care Health and Safety Resource Center at UNC-Chapel Hill provides guidance on the most important components of EPR Plans in the immediate aftermath of a disaster, such as emergency contacts, licensing and environmental health contacts, and facility and program information that staff will need when communicating about their needs.

In addition to providers knowing how to use their plans, there is an opportunity for support agencies to also create plans, and to collaborate regionally, said Lori Jones-Ruff, regional programs manager at the Southwestern Child Development Commission (SWCDC), a regional CCR&R agency serving the seven westernmost counties of North Carolina, plus the Qualla Boundary and Buncombe County.

“We need to get together on the front end and say, if a natural disaster happens, what’s the steps that all of us need to agree to?” Jones-Ruff said. “How do we get together and get our ducks in a row and say, ‘OK, Southwestern is going to handle this, this partnership is going to handle this, this agency is going to handle this,’ so that we’re dividing and conquering.”

At the state level, the Child Care and Development Fund, the largest federal funding stream for child care, requires each state to develop a disaster plan. Yet the level of knowledge about DCDEE’s disaster plan among local partners was limited, said Greg Borom, director of the WNC Early Childhood Coalition, a regional advocacy organization.

“I’m going to be paying a lot more attention to that plan, looking at how we’re trying to set the pieces in place through that planning process, so there can be a rapid response and that the right organizations are connected and communicating,” Borom said.

The plan is reviewed and revised annually by DCDEE and outlines the responsibilities of state teams and partners during disasters.

During Helene, it informed leadership structures, communication with providers, data collection and assessment, and collaboration with partners, according to an emailed statement from DHHS.

The DCDEE Executive Disaster Team met daily to assess the storm’s impact and programs’ needs and adjust their response. The division also continued payments of the child care subsidy program, which helps low-income families afford care.

For the month of October 2024, facilities in the affected counties did not have to submit attendance information, which normally dictates how much subsidy funding a provider receives. Instead, children who were enrolled were automatically marked as “present.”

The division also worked with the Governor’s Office on an executive order to grant flexibilities to programs to waive regulatory requirements to serve children and families.

![]() Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

Sign up for Early Bird, our newsletter on all things early childhood.

DCDEE will begin the process of revision of the disaster plan in June 2026, according to DHHS.

The WNC Hurricane Helene State Child Care Task Force was established to communicate the region’s child care recovery needs, and is led by Amy Cubbage, president of the North Carolina Partnership for Children (NCPC), the umbrella organization for the state’s 75 local Smart Start partnerships.

The task force is shifting its focus to proactive disaster preparedness of the statewide early childhood community and hopes to inform the revision of DCDEE’s disaster plan, Cubbage said.

“We have a little bit of a time now where we can look up and say, ‘OK, let’s really think through, how can we be better coordinated, better aligned, faster even than we were?’” she said.

NCPC staff compiled a list of disaster preparedness and post-disaster assessment questions after EdNC asked how the organization was learning from its Helene response. The questions might be useful for other state-level early childhood organizations, support agencies, and child care programs.

Communication

Providers need plans to communicate without cell service or internet access, local educators said. And at the regional and state levels, better coordination among different types of organizations could make things easier and more efficient.

Simpson, the Smart Start director at the partnership serving Yancey, Mitchell, and Avery counties, said trying to reach people the first week after the storm was “a wash.” Without cell service or internet access, contacting her organization’s staff, as well as families and child care providers, was impossible. Simpson was the last person her organization could reach because of the storm damage to her home and neighborhood.

In less isolated areas, she said, her staff started going to homes to check on people, first prioritizing child care directors.

“Just trying to put hands on folks was the first piece,” she said.

If they could get to directors, they would then ask about teachers and families. One staff member, Simpson said, happened to know where some of the teachers lived and tried to physically reach as many people as possible.

“It was just a lot of neighbor helping neighbor in those very earliest days,” Simpson said.

Amy Barry, executive director of Buncombe Partnership for Children, the local Smart Start agency, described child care programs hanging physical signs on their doors about their status and other information because they were unable to communicate with parents any other way.

Rebecca Ayers, program director at Intermountain Children’s Services, Inc., which operates six child care programs in Mitchell, Yancey, Avery, and Watauga counties, said she would leave physical notes to colleagues in her administrative office.

It was at least three weeks before all of her staff were accounted for and well over a month, Ayers said, before she knew all of the children and families she serves were OK.

“There was no way to really correspond outside of that, and so I would come by the office and I would leave a note that said, ‘Hey, I’m fine, leave your name and let me know you’re OK. If you hear from staff, please write them down.’”

Ayers traveled to specific areas she heard had cell service or internet. In the first couple of days after the storm, she left a note at the office and was able to coordinate with the organization’s fiscal officer to meet at the fire department, which had internet access, to deposit funds into her staff’s bank accounts.

“We knew that we had to get payroll out somehow,” Ayers said. “People were going to need money for gas and generators and to get to help.”

Ayers said her region was unable to use ATMs or debit cards in the first few weeks. Some staff in Yancey and Mitchell counties were able to travel to Tennessee to make withdrawals.

Once DCDEE and local support agencies accounted for their own staff, they started reaching out to programs across the impacted region and keeping track of their status and their needs.

“It was everybody trying to, just touch base, first and foremost, with your own teams, so that you could figure out, did everybody make it through? Is everybody safe?” said Jones-Ruff with SWCDC. “Until we get them situated, who do we have that can even reach out to providers?”

Though Smart Start partnerships, CCR&R agencies, and DCDEE licensing consultants tried to streamline communication, there were a lot of agencies reaching out to providers at once, Jones-Ruff said.

“All of the support agencies were stumbling over on top of each other,” she said.

DCDEE, according to the emailed statement, was able to reach all licensed providers in the region within a month.

WNC Early Childhood Coalition’s Borom said communication — both how to communicate in the absence of regular channels and who should be in touch with who — should be part of how the state revises its plan.

“The planning process will determine what those first two weeks are going to look like,” Borom said. “What does our CCDF disaster response plan look like? Who is mobilized to be around that state task force? Do advocates and providers know that it exists?”

Building communication and relationships ahead of time will make a big difference in those immediate days and weeks, he said.

“That’s the kind of lesson learned about why you need to be paying attention now — as things are written and new things are being envisioned,” Borom said.

Reopening

Once communication channels were open, providers and their support networks started the process of reopening.

“Once we got past the, ‘You’re OK,’ we moved into the, ‘What do you need to open?’” Simpson said.

Simpson said working with Save the Children in the immediate aftermath helped her clarify her role among so many challenges and competing priorities.

“What we learned about their work in war zones and famines and situations like that was what needs to happen is kids need to get back to learning,” Simpson said. “That was just a place where we felt like we could find our role in all of the chaos that was going on everywhere: What can we do to help kids get back into their centers, to get kids connected back with their teachers?”

DCDEE licensing consultants, along with support organizations like Simpson’s, helped providers assess damages and meet reopening requirements.

Normal licensing requirements were loosened during the state of emergency. DCDEE’s disaster plan outlines the roles of several agencies that might need to be involved in inspections depending on the program’s circumstances: local environmental health specialists, local building inspectors, and local fire inspectors. Licensing consultants, the plan says, should help directors or owners contact and work with various partners and address hazards before reopening.

The NC Child Care Health and Safety Resource Center’s immediate post-disaster resources include a self-assessment for providers to complete before or as they are contacting key partners.

The assessment encourages providers to document as much as they can, taking photographs and videos if possible, and to consider what might be helpful for licensing consultants, environmental health specialists, and insurance reimbursement.

It walks providers through assessing debris, structural damage, the status of the playground, water access, impacts on food, the program’s electrical operating system, smoke/carbon monoxide detectors, the sewage or septic system, and the HVAC system.

Helene damaged water and waste management systems, and, in some areas, communities were lacking clean drinking water for more than a month. That meant many providers without other damages were ready to reopen but needed access to water for cleaning, hand-washing, and drinking.

Teams of consultants, environmental health specialists, providers, and support personnel were weighing safety considerations when making reopening decisions.

In Mitchell, Avery, and Yancey counties, a team met on Zoom and decided that centers could reopen with potable water and port-a-potties, according to Child Care Resource & Referral Coordinator MaryLee Yearick, who works at the Blue Ridge Partnership for Children.

Simpson said multiple providers rented trailers with port-a-potties from a company in Marion. The partnership helped coordinate “water buffaloes,” large water containers, to programs.

In Asheville, the Christine W. Avery Learning Center bought camping sinks for each classroom, each bathroom, and the facility’s kitchens, and then bought a subscription to a company that sent five-gallon jugs of water, said CiCi Weston, owner of the program.

For some, alternative water plans were a hurdle to reopening without clear guidance on what was and was not required, Barry said.

“Families who needed to be at work and did not have access to their regular child care provider were finding that very frustrating,” she said. “And you know, unfortunately, the directors were doing all they could, but needed to be sure that their plan was approved.”

Some programs’ plans were rejected by DCDEE more than once, Barry said. Once a provider’s plan was approved, her staff shared a template with other programs to speed up the process.

“If we knew what the plan requirements were, then we could have acted more quickly in order to get approved water containers,” Barry said. “That’s an important lesson learned for sure.”

DCDEE expects emergency water options, as well as communication around different water advisories, to be added to the state plan, according to the DHHS statement.

“Some of the challenges we worked together to resolve alongside providers included how to address water supply and boil water notices as many facilities had not previously experienced a disaster with impacts of this magnitude,” the emailed statement says. “As a result, DCDEE may include additional information, in collaboration with the NC DHHS-Division of Public Health and the NC Child Care Health and Safety Resource Center, to the 2026 plan related to collaboration with partners for disposable supplies, water tanks, and coordination of water delivery.”

Moving to temporary locations

Some child care programs relocated to temporary locations to continue serving children while their facilities were repaired. Temporary care arrangements are allowed in the state disaster plan when facilities are damaged or unable to meet families’ needs.

In downtown Boone, Halee Hartley, owner of Kid Cove, offered a new facility to the children and staff of Mountain Pathway School, a Montessori program.

Buncombe County’s Christine W. Avery Learning Center relocated the children enrolled in its Swannanoa location to its two other sites in Asheville.

The staff of Yancey County Head Start, which was closed until December 2024, hosted play groups at the local library to allow children to socialize and to connect families with resources.

And in Burke County, a partnership between Burke County Smart Start and Burke County Public Schools resulted in two child care programs operating from local public elementary schools for several months.

Children and staff from the county’s two largest child care centers — Quaker Meadows Generations, a Head Start program, and Creative Beginnings Day Care, a private center — were displaced after the storm flooded the facilities.

Related reads

Five classrooms of children ages 3 to 5 from Quaker Meadows operated out of Salem Elementary School from mid-October through the rest of the school year. Three classrooms of preschoolers from Creative Beginnings relocated to Oak Hill Elementary from mid-October to December.

“I think it just speaks volumes of the community, the camaraderie, the kindness, the legacy that’s being built here,” said Jessica Powell, a teacher who had worked at Creative Beginnings for 17 years at the time of the storm, in an EdNC interview in October 2024.

It was a close relationship between Jacquie Grady, Burke County Public Schools’ preschool and kindergarten transition coordinator, and Kathy Smith, executive director of Burke County Smart Start, that made the partnership possible and connected children back with their teachers so quickly.

Upon hearing the news of the damage to the two programs, Grady immediately started identifying free space across the district that could house young children. Smith worked with a state licensing consultant on emergency licensing requirements.

“Everybody just pitched in and did what was necessary to get children served,” Smith said.

The district did not charge the programs for rent or utilities. The child care centers bought food from the district for children to eat in the school cafeterias.

Providers and local leaders said reconnecting children with a sense of routine and normalcy was their main priority.

“My biggest concern was getting the children back as soon as possible,” said Stephanie Ashley, executive director of Blue Ridge Community Action, the nonprofit that runs Quaker Meadows.

Coordinating supplies

Several support agencies began collecting donations of furniture, supplies, food, clothing, and equipment, acting as distribution centers and coordinating deliveries and volunteers.

“It was one of the most outstanding logistical feets I’ve seen in my career,” NCPC’s Cubbage said. Local partnerships sought donations tailored to the needs of young children like diapers, formula, and wipes.

Harnett County Partnership for Children, which had experience in hurricane recovery in the eastern part of the state, acted as a regional hub for donations. Wilkes Community Partnership for Children and The Iredell County Partnership for Young Children, which are located in areas that experienced less damage, acted as western hubs, splitting up the impacted counties and making deliveries to programs across the region.

SWCDC served as a hub in Jackson County. Director Jones-Ruff said the organization is in the planning process of creating distribution sites in targeted areas so that, in future disasters, the local staff will not have to rent U-Hauls and make deliveries across counties.

The organization has identified seven distribution sites that cover 18 counties, she said. As national partners come into the area, the idea is that SWCDC will be able to better coordinate the right materials to the right locations.

They are prioritizing child care providers and health care providers who serve low-income families, and working with Save the Children, Baby to Baby, and Good360, she said.

Jones-Ruff said this distribution network could save time and money — and might be useful in periods of normal operation as well as during disasters.

Navigating relief

In the aftermath of a disaster, it is not always clear where to turn for financial relief. In the world of child care after Hurricane Helene, that was especially true, local leaders said.

“There is no big mechanism for money to work its way into a community post-disaster,” said David Jackson, CEO of the Boone Area Chamber of Commerce. “It flies from a million different directions. Some of it is highly specific. Some of it is promised and not delivered.”

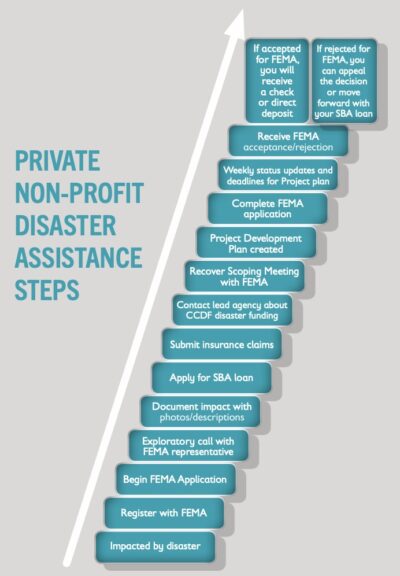

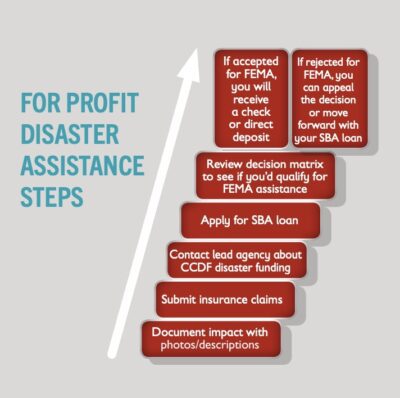

Child care programs that are for-profit, private businesses are ineligible for FEMA assistance. For-profit programs may instead access Small Business Administration loans, which provide small businesses with up to $2 million in loans with lower-than-normal interest rates.

Though nonprofit child care programs fall under eligible “non-critical social services,” according to a January 2025 FEMA Public Assistance Program and Policy Guide, it is rare that child care programs accesses this assistance, according to Save the Children. The nonprofit estimates that 10% of all child care providers access FEMA funding.

“The expectation from the government is often that whatever gaps are left that federal infrastructure doesn’t fill, insurance or the private sector will fill,” said Kristen Martinez Gugerli, a federal lead associate of public partnerships at Save the Children. “But of course, we saw with Helene that … because it was such an unusual storm, and this part of the country isn’t really used to getting hit with hurricanes, a lot of these child care providers didn’t have flood insurance, so that exposed a big hole in that argument.”

This child care FEMA funding guide from Save the Children, created for Texas child care in January 2022, also applies to programs across the country. The embedded decision matrices walk providers through relief assistance steps depending on program type.

Quick and nimble philanthropy

With a lack of significant public relief on the way for child care, local support agencies, advocates, and providers themselves began communicating their needs to private funders.

Jackson and the local chamber of commerce was one of those connectors.

“There were people that, through Herculean efforts, got their doors open again so their children could be taken care of — so volunteer work, emergency work, first responders could go to work, all of those people that needed to come together to start building the community back — could do it and not have to take their 3-year-old along with them. … But there was no money coming to do that,” Jackson said. “It wasn’t like the government said, ‘Here’s your chunk of money for community child care stabilization.’ We had to learn that first and then act on it.”

Just days after the storm, Jackson ran into Halee Hartley, a local child care program owner and Boone Area Chamber of Commerce board member, in the grocery store. She mentioned she was considering closing her program.

“When the storm hit, I could not charge my 125 families tuition knowing that some have lost access to their homes,” Hartley said. “Some are moving away temporarily to just be in a safer place. But here I am. Rent is still due. Bills still have to be paid. I still have 42 employees that have to be paid. So in my mind it was, ‘OK, I’m just gonna shut my doors.’”

Meanwhile, the Boone Area Chamber of Commerce’s foundation was seeing “an influx of cash in a very short period of time that came from people far and wide, all over the world, really,” Jackson said.

Up to Sept. 26, 2024, the foundation had raised about $15,000, said Ethan Dodson, director of development at the foundation. In the couple of weeks following Helene, it raised over $200,000. Chamber leaders pulled the foundation board together to figure out how to prioritize that funding.

Related reads

The Boone Area Chamber of Commerce had already established partners in the child care community through pre-pandemic efforts to expand access and lower costs for families. From a recent conversation with one of those partners, Jackson brought up the cost of covering one month’s worth of tuition for all of the child care programs in the county: $125,000. It would be a strategy to directly support child care providers, the families they serve, and the rest of the local economy.

“We felt like it could be a twofold situation, where we could support the industry, make sure they could pay their bills, pay their staff, and be ready to open the doors again when things got a little bit more normalized — but also it would put money in people’s hands pretty quick,” Jackson said.

So Jackson and Elisha Childers, executive director of The Children’s Council of Watauga County, went on the radio and announced they would be covering tuition for all children enrolled in child care programs for the month of October. With additional funding from Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation, the allocation came to $280,000. The funding was distributed to providers through The Children’s Council of Watauga.

“Child care centers are businesses, and they are incredibly important ones,” Jackson said. “If we’re going to stabilize our business community, we have to stabilize this industry first so we can make sure that the rest of it can come back together again.”

The Community Foundation of Western North Carolina, Dogwood Health Trust, and Save the Children gave quick and nimble funding to help programs repair buildings, reopen, and cover lost revenue. These grants mainly went through local Smart Start partnerships and CCR&R agencies and then to individual providers.

Jones-Ruff at SWCDC surveyed providers in the weeks following the storm about their top financial needs. Programs said they needed support to retain staff members, and then the commission forwarded that information to private funders.

Jones-Ruff said funding to retain teachers was important to meet families’ needs in the short-term and for the long-term stability of the early childhood workforce.

“Once the teachers leave, if there’s going to be that period of time where there’s not going to be work, or they can’t work, the likelihood that they will return to an early childhood classroom is low,” she said.

Related reads

By February 2025, the Buncombe Partnership for Children had distributed $3 million in private funds, including covering 85% of programs’ lost revenue and staff retention bonuses of $500 to 900 people, said Barry, executive director of the organization.

Simpson at Blue Ridge Partnership for Children said she kept a spreadsheet with all the different funding streams and their allowable uses and required documentation. She tried to create a single application for child care programs and, depending on their needs, match them with the appropriate funding source. The flexibility and minimal documentation that accompanied philanthropic dollars was greatly appreciated, Simpson said.

“Being so responsive and so trusting and easy to work with has been a remarkable experience,” she said.

Smith, in Burke County, said her close relationships with the school district, as well as several philanthropies and community partners, made the organization’s response quicker and easier.

“Keep a profile in your community of making connections with people — and true connections,” Smith said. “Build relationships, because I think it all comes down to having relationships, having trust in folks.”

State relief

The Office of State Budget and Management (OSBM) estimated $36 million in child care recovery needs in October 2024, and $86 million in the office’s updated needs assessment in December.

The December estimate included $12 million in facility damages after insurance and other forms of assistance, $52.6 million for operational costs including staff retention, $16.6 million to cover parent fees for those receiving subsidies, and $4.8 million to support programs providing full-time care to school-age children because of public school closures.

The state legislature’s sole child care relief allocation was $10 million in its second Helene relief package on Oct. 24, 2024. The state allocated this funding to DCDEE to then give to the North Carolina Partnership for Children (NCPC) to distribute among the local Smart Start partnerships in impacted counties. The partnerships were then responsible for giving the money to individual programs.

“Partnerships will use the funds for affected child care centers and family child care homes to provide assistance in reopening and maintaining operations, including, but not limited to, cleaning, repairs, and relocating,” according to the legislation’s money report.

Related reads

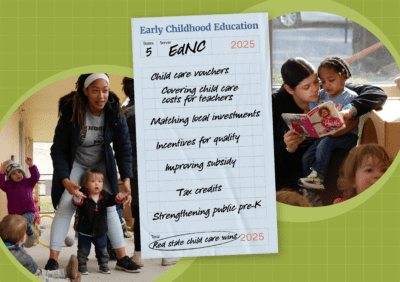

Many programs were struggling financially before the storm, Cubbage said. Advocates had warned that a funding cliff as pandemic-era stabilization funds dried up could lead to further instability, including child care program closures. Long-term state investment was needed to meet families’ demands, they argued.

Then Helene hit. The stabilization funds ended in March 2025.

“This was creating the potential for real backsliding of the supply and loss of a lot of child care centers and programs if we didn’t shore up operations,” Cubbage said. “And so the hope was to get that aid out as quickly as possible.”

The funding did not get to partnerships until February 2025. And as of December 2025, the local partnerships were still disbursing the first half of the funding.

“It did hit bureaucratic snags,” Cubbage said.

Cubbage, along with Smart Start leaders and providers, said strict documentation requirements have slowed the process further.

“We’re trying to get dollars out as fast and efficiently as ever we can,” Cubbage said. “I think, providers and all of us were feeling, ‘Absolutely not $1 can be wasted. Document everything’ … At the time of disaster that coincides with, ‘Wait, all my documentation went down the river’ … It’s just not feasible.”

Barry said a staff person at her organization has spent 90% of their time reviewing applications, following up to get more supporting documentation, and helping providers figure out how to access that documentation.

The documentation, Barry said, “really has been a challenge and a burden for child care providers to come up with.”

Simpson said the state allocation was “a tremendous victory,” and that the funds have been harder to use than the philanthropic funds the organization has received.

“It is a big ask to ask a child care provider, especially for something that happened in the first month after the storm, do you have a credit card payment or your bank statement? Well at that point, everything was in cash because there was no power,” Simpson said.

Simpson said she is planning to use the state funds for mental health supports for providers and ongoing facility repair needs.

As the WNC Hurricane Helene State Child Care Task Force makes plans for future responses, Cubbage said the process should be sped up and improved — centering the needs of those closest to children and families.

“People on the ground have the best knowledge, they have the fonts of wisdom of who’s in need in their community,” she said. “They have eyes on the families. They have the understanding of community partners that might have resources to provide and how best to coordinate that, and what state partners need to do. And I hope we’ll do better next time in providing greater trust and flexibility for local partners to be able to get the dollars out in a less burdensome way.”

Federal relief

Though Congress did allocate $250 million in child care relief across states in December 2024, it is unclear how much of that funding will go to North Carolina programs.

DCDEE will hear back about its funding request by Sept. 30, 2026, according to DHHS. The funding covers impacts of natural disasters in 2023 and 2024.

DCDEE requested $91.5 million in September 2025 from the national allocation through the Administration for Children and Families’ (ACF) Office of Child Care (OCC) for recovery from two 2024 declared disasters: about $3 million for Tropical Storm Debby, about $57 million for Hurricane Helene, and about $31 million in assistance across areas impacted by both storms, according to a DHHS statement. The division has been assessing programs’ ongoing needs through the Disaster Impact Report Portal.

“Officials from ACF shared that applications from multiple states had been received and totaled more than double what was allocated federal supplemental disaster recovery funds in FFY 2023-2024,” the DCDEE statement said.

“North Carolina’s application included supports for construction, major renovation, and alterations; materials, supplies, furnishing vehicles and equipment; quality improvement activities such as Western NC recovery grants, expansion of the Child Care WAGE$ program, workforce development, and child care supply; mental health consultation or services; and statewide regional emergency preparedness and response events,” according to the DCDEE statement.

The delays have real implications for children, families, and programs, said Martinez Gugerli with Save the Children.

“We’re talking two or three years that a lot of child care providers are going without getting this critical assistance,” she said. “In the meantime, the already existing needs that were there before the storm have just been really exacerbated.”

Ongoing mental health needs

Beyond physical and financial recovery, every child, caregiver, educator, and leader who experienced the chaos and loss of the storm is navigating a healing process.

Educators need particular support because of the critical role they play in children’s lives during periods of disruption, said Rooks, who has led mental health training with providers and support personnel since Helene.

“Who are the adults who take care of kids, and what supports do they need in order to provide support to kids who have just experienced something really outside of what they’re used to?” she said.

Educators are working through their own loss while providing care to others.

“It can be stressful on the best of days,” Rooks said. “After a disaster, when it is not the best of days, and maybe you’re going home and your water is not on and you don’t have clean laundry, but you’re also working with kids all day, that builds and it can wear on you.”

Save the Children and SWCDC registered the organization’s psychosocial trainings with DCDEE so that teachers could receive credit for their annual professional development requirements. That credit is now in place for future emergencies.

The emotional highs and lows of disaster recovery come at different times for different people, Rooks said. But it’s often a longer process than one might expect. The National Center for PTSD outlines four phases of recovery: impact, rescue, recovery, and reconstruction.

“A lot of times when a disaster hits, people would expect immediately after the impact to be the lowest, but research actually tells us that’s not the case at all, and that it tends to be a lot later on,” Rooks said. “Because at first, you’re just focused on all the things you need immediately. Over time, when you get more tired and your resources are more stretched thin — that’s when we start to see a lot of the biggest stressors.”

Local support agencies and individual programs have started informal listening sessions and professional therapy services for adults navigating trauma.

In Buncombe County, the local Smart Start partnership purchased a “Teddy Bears in Classroom Practice” program from Bank Street College of Education’s Center for Emotionally Responsive Practice. Burke County Smart Start has started the same program.

“It’s simple, and beautiful, and was immediately impactful,” Barry said.

Each child receives a bear, which Barry’s staff delivers to child care facilities while explaining the program to teachers. Children are asked to name the bear and receive some accessories to accompany the stuffed animal, which stays at the program and is not taken home. The “transitional object” helps children express uncomfortable feelings and self-soothe, Barry said.

“One child never comes to circle time, but came and stroked his bear the whole time,” she said. “Another child went to their teacher holding their bear, and said, ‘My bear is very sad today.’ And the teacher’s like, ‘Why do you think they’re very sad?’ And the child said, ‘The bear misses her mommy.’ And the teacher said (that) this is a child that never talked about their feelings.”

Consistent investment in local resources is needed, she said.

“Mental health supports are critical, and it’s not like there’s a quick fix,” Barry said. “There’s going to be an ongoing need for a range of mental health supports, whether it’s expressive arts therapy or certain materials in the classroom.”

Ayers, the program director with six sites across the region, said the lack of local resources has been a challenge.

“Our area was considered a mental health desert before Helene, with no resources, especially for children,” she said.

Ayers is planning a trauma-informed training for pre-service teachers at her programs in the coming year and working with Save the Children to get resources for teachers to use with children and families.

Through the entire experience, Ayers said she has tried to prioritize basic human connection.

“Sometimes early childhood folks get swept away with requirements, screenings, making sure children are learning numbers and letters — none of that was important,” she said. “Connection was important, meeting our basic needs, relying on each other.”

Strengthening systems, building family resiliency

Local and state leaders from early care and education, philanthropy, and government convened in Raleigh in August 2025 to discuss how to build resilience for young children and the systems that serve them after “climate disasters and other weather-related events.”

The work, funded by the Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust and hosted by national think tank Capita and NCPC, led to several recommendations:

- Prioritizing direct support to families and communities. The report says that cash assistance directly to families or through mutual aid allows parents and caregivers to make choices that best serve their children. It also says investment is needed in family-facing organizations like local Smart Start partnerships that serve as “lighthouses” in recovery and “a vital social infrastructure that helps to anchor local networks in care, trust, and coordination.”

- Philanthropy’s role in reframing narratives and building political will. Outside of stepping in after disaster, philanthropies should look past short-term programs and efforts and engage in long-term change, the report says. They should also be investing in resilience proactively, not just responding to emergencies. “What is most needed now is not only innovation in policy design, but also in new approaches to organizing, storytelling, and collaboration,” the authors write.

- Reframing early childhood beyond programs. Addressing the root causes of family stress is needed to foster the connections children need in the critical early years of life. Programs are important, but strengthening families should be the basis of early childhood change-making, the workshop found.

The workshop also asked attendees for “moonshot” proposals — big asks that would lead to more resilient families and communities. Along with receiving cash assistance for up to a year after a disaster, proposals included that families with young children should have access to public goods like health care, paid parental leave, and universal child care. The report also suggested establishing a permanent, universal child tax credit.

“Family resilience requires more than responsive aid; it depends on baseline economic security and sustained investment in families and communities,” the authors wrote.

The region’s child care programs and professionals need some of the same support to recover as they do all the time, advocates and providers said. Programs need stable and consistent funding to provide quality care at an affordable price. Educators need livable wages, access to health and mental health supports, and professional development.

“We have to figure out a way in this state to keep high-quality programs operating and running and children’s needs being met,” said Jan Wyatt, owner of Creative Beginnings Day Care, one of the programs that was flooded in Burke County. Wyatt also lost her own home in the storm.

The program lost everything, and though Wyatt said the support of the community was overwhelming, reopening by December 2024 was still “a huge financial cost,” she said.

When pandemic-era stabilization grants ended in March, Wyatt figured out a way to sustain the wages of her teachers without increasing tuition. She said she was considering a tuition increase in January 2026 to continue paying competitive wages.

Experts consider the child care industry a “broken market” because businesses cannot produce the desired product, high-quality care, at a price most families can afford. Since the pandemic, advocates have been pushing for long-term solutions. Gov. Josh Stein established the NC Task Force on Child Care and Early Education in March to explore those solutions. The state legislature this session did not allocate any new funding for child care.

Related reads

Since Helene, the WNC Early Childhood Coalition has launched a Recover/Rebuild Network to continue centering child care in the state’s recovery conversations, and making connections between hurricane recovery and the need for systemic child care investments.

The network is asking “What are those kinds of things we can advocate for to make sure child care is shored up?” said Borom, the coalition director.

“That’s the question that every county in the state is asking about their child care,” he said. “It’s in a crisis, regardless of whether you were in the path of Helene or not across the state. Recover/Rebuild has specific things we’re looking at around Hurricane Helene recovery, but also it’s part of the larger effort to try to shore it up from mountains to sea.”

Checklist for child care programs and support agencies

- Have you checked local news sources and local government agencies to see if there are any notices or advisories that impact child care programs?

- Do you have physical copies of contact information and home addresses for staff and families? In the event of communication barriers like lost cell service and internet access, do you have a physical location to have in-person conversations if safe to reach?

- Do you and/or the programs you serve know how to utilize their Emergency Response and Preparedness Plans, including their Ready to Go file?

- Do you have key details from the EPR Plan updated and ready, like the facility address, enrollment information, utility information, and floor plan?

- Do you have physical copies of contact information for your licensing consultant, local environmental health specialist, local Smart Start partnership and/or CCR&R agency, and child care health consultant?

- Do you have physical copies of contact information for utility services for problems with water, electricity, and gas? Do you have contact information for professionals like plumbers, electricians, HVAC technicians, or carpenters?

- Have you assessed damages, and taken pictures and video for recovery and restoration? Do you have a printed copy of the Immediate Post-Disaster Self-Assessment for Early Educators from the NC Child Care Health and Safety Resource Center?

- Do you need alternative water sources, and do you have an alternative water plan template? As a support agency, do you have alternative water plan templates to share with programs?

- For support agencies, have you coordinated with each other and DCDEE to know who is reaching out to providers and what each organization’s role will be in communication efforts?

- For support agencies, do you know where to collect donations and how to coordinate deliveries?

- Do you have relationships with donors and/or philanthropies to meet the needs of children, staff, and child care programs? What are there immediate needs, and how are those needs changing?

- Do you know how to communicate your needs and the needs of programs to advocate for and access public relief funding from the local, state, and federal levels?

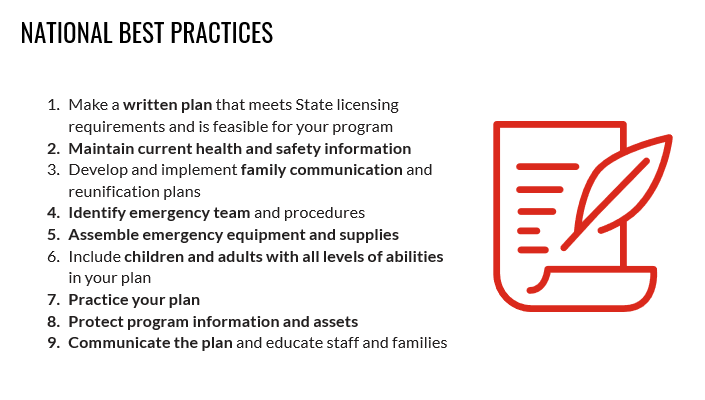

The following is a list of national best practices in emergency preparedness for child care providers from Save the Children.

Editor’s note: The Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina Foundation and Dogwood Health Trust support the work of EdNC.

Recommended reading