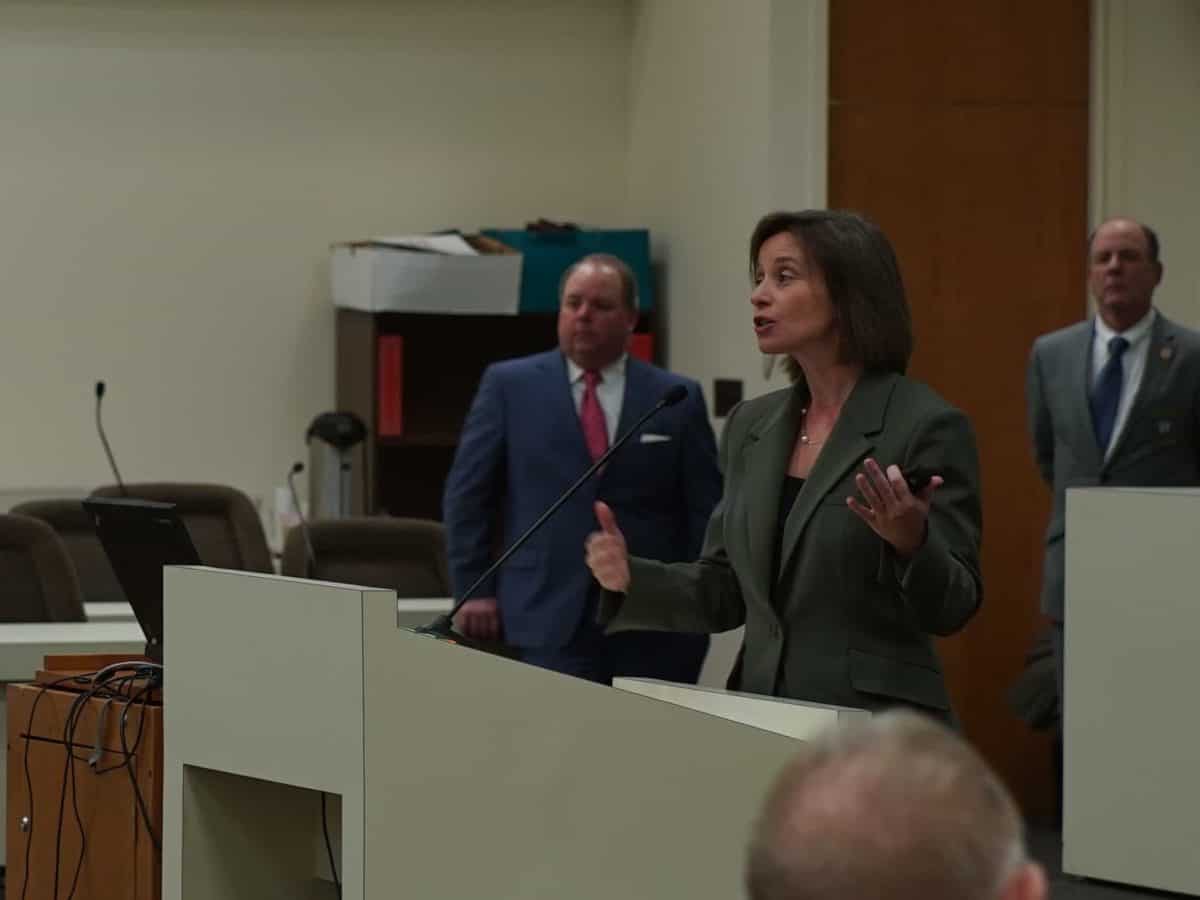

Lawmakers heard from leaders of several state education programs at the Joint Legislative Education Oversight Committee meeting on Tuesday. At the committee’s final meeting of 2017, representatives heard updates and future plans on North Carolina’s new laboratory schools, Teaching Fellows program and the state’s community college system.

Lab Schools

The state’s first two lab schools, K-8 institutions based in universities, opened this past year, partnering with East Carolina University and Western Carolina University.

Sean Bulson, interim vice president of university and P-12 partnerships, reported on the first year of the program’s 3-year plan. Next year, Appalachian State, UNCG and UNCW will open lab schools and UNCP, UNCC, NCCU and a ninth unidentified institution will join them in 2019.

While the original legislation required 25 percent of schools in the district to be low-performing, later modifications relaxed the requirement. Nonetheless, 63 percent of students attending the state’s laboratory schools were previously enrolled in low-performing schools. Most students are African-American, and the majority are male. Bulson said 80 to 90 percent of students at ECU’s lab school come from poverty, while WCU has significantly fewer.

“The experiences I’ve had a chance to see is that these are students who have struggled in the past in other settings.” Bulson said. “The attention and care I’m seeing… they’re taking tremendous care of these students.”

“Focusing on students in low performing centers is one of the most important parts of this legislation,” he added.

Students are connected to the schools through a recruitment process that culminates with a simple application. ECU’s lab school had 104 applicants and 74 enrolled, while 74 applied to WCU with an enrollment total of 57. Bulson said schools in the pipeline will be significantly bigger.

The discrepancy in numbers was not due to rejected applicants, Bulson said, but rather students choosing not to attend. The current legislation uses a school choice model on a first-come, first-serve approach with a waiting list, although at the beginning of school, the waiting list at ECU was empty.

Bulson emphasized the need to develop common standards for the schools while also customizing each one on an individual basis.

“The idea here is to be looking at best practices,” Bulson said. “We’re developing a network across the state.”

He said the idea was to strike a balance between independently-tailored programs and statewide standards, and he noted that partnership with universities helps ensure lab schools have higher quality teachers, especially those best suited to individual communities.

“[The laboratory school at] ECU has designed something significantly around health, because that’s a huge asset at ECU,” Bulson said.

Bulson asked the committee for budget adjustments on child nutrition, employment considerations, criminal history checks and financial reporting.

Current legislation does not provide universities with the ability to purchase new property for the schools. As a result, although the lab schools operate independently with their own principal and staff, they use the facilities of current public schools.

Funding is recurring, evaluated on a five-year basis. Bulson said that although the state’s Department of Public Instruction has been a great partner for laboratory schools, “Every little policy, every little process they have, needs to be tweaked for lab schools.”

He addressed questions about the effectiveness of communication between the UNCGA and DPI since both organizations use different financial reporting methods.

“Our systems do not talk to each other well,” Bulson said. He said that finding the best method to clearly communicate financial reports will be very important in the future. Reports are presented every November.

Teaching Fellows

Sara Ulm, director of the NC Teaching Fellows Program, addressed the committee on the progress of the program. The first scholarships will be awarded in 2018.

“The purpose of the program…it’s to recruit, prepare, equip, and produce highly-qualified educators in the STEM and special education fields,” Ulm said.

Of 16 qualified applicants, the five universities chosen as Teaching Fellows partners were Elon University, NC State, UNCC, UNC-Chapel Hill and Meredith College. They had the five highest scores in a three-part application that included eligibility requirements, legislative mandated criteria and supplemental information.

Several legislators raised concerns about the selection of institutions as no historically black colleges or universities were selected, and the selected schools are geographically similar, with a lack of representation from the eastern part of the state.

Ulm reiterated that the test was designed as objectively as possible and that if the program is successful, it plans to add more institutions. Other legislators praised the objective, well-documented applicant testing. Ulm also noted that current legislation requires there to be both public and private schools involved in the program, so a lower-scoring private school could theoretically take a place on the list above a public school if there were no private representation.

“The appointments were made before I was hired, so I wasn’t a part of those conversations,” Ulm added.

The requirement that recipients enter STEM or special education is new for this iteration of the Teaching Fellows program. The program is also newly open to applicants other than high school seniors, including students applying to or already enrolled in educator preparation programs at one of the five partner institutions, and individuals with existing bachelor’s degrees in other areas.

The first class of teaching fellows will be 163 students who will begin in August 2018. The program will aim for a 1:1 ratio in low performing schools and a 1:2 ratio in non low-performing schools. Ulm said that this is to drive good teachers into the low-performing schools that need them most.

Community Colleges

Jennifer Haygood, acting president of the North Carolina Community College System, concluded the committee meeting by laying out a plan for the future of community colleges across the state.

Haygood said the board had listened carefully to input from businesses, students, and the colleges themselves, including work in small groups. As a result, the board was able to create a strategic plan based in four core areas: student interest and access, student progress and success, workforce and economic impact, and system effectiveness.

They established four teams to deal with those four issues, each co-chaired by a system office vice president, and presidents or vice presidents from various community colleges.

As the state’s population grows, the board is changing the way they reach students, Haygood said. An increase in diversity and working-age population means fewer traditional age students. Non-traditional female students have gained increased importance in particular.

“We all know that our state is undergoing a lot of demographic change,” she said. “That change very pivotal to how we think about the future of our system.”

For increasing completion, Haygood noted that establishing a career goal early is important. That also means reducing achievement gaps that occur along geographic and demographic lines.

By 2020, Haygood said, it is estimated that 67 percent of jobs in NC will require post-secondary education. Since only 48 percent of working age adults in the state had a post-secondary degree as of 2015, there is a significant gap that needs closing. Seventeen percent of children under the age of 10 in North Carolina are hispanic, but 63 percent of those children do not have either parent with a secondary degree.

Haygood said a major focus for the colleges in the near future is expanding from academic and trade skills to soft skills.

“We heard a lot about how folks will hire someone with the technical skills, and they’ll get fired two weeks later because they didn’t know how to act when they got to work,” she said.

The board is also interested in removing barriers for students — not just tuition fees, but more invisible barriers such as excess costs for transportation, child care, and books. Haygood said providing more flexible scheduling options is important, especially as more students enter community college at a non-traditional age.

The system currently uses performance-based funding, but before asking for funding increases using those data, the board wants to make sure the statistics are collected as fairly and accurately as possible. Haygood noted that other measures of success are important too, pointing to the need to create a prepared workforce so that future employment rates will increase.

“Unfortunately, about 40 percent of our state’s employers are saying they’re having a hard time hiring,” Haygood said. “We think that workplace learning is an important strategy for how students can connect what they’re learning in the classroom to the workforce.”

The final goal is to improve overall system effectiveness. “Our community college system will not be able to meet its mission as it should if we don’t get better technology to support its institutions,” Haygood said. “Our current technology has served us well, for a while, but it needs to be updated.”

She said that colleges could be doing more collectively rather than individually, and that there is a need for more cohesion and a consistent voice.

“We sometimes joke that [community colleges] are the best-kept secret in North Carolina, and that’s not a good thing,” Haygood said.