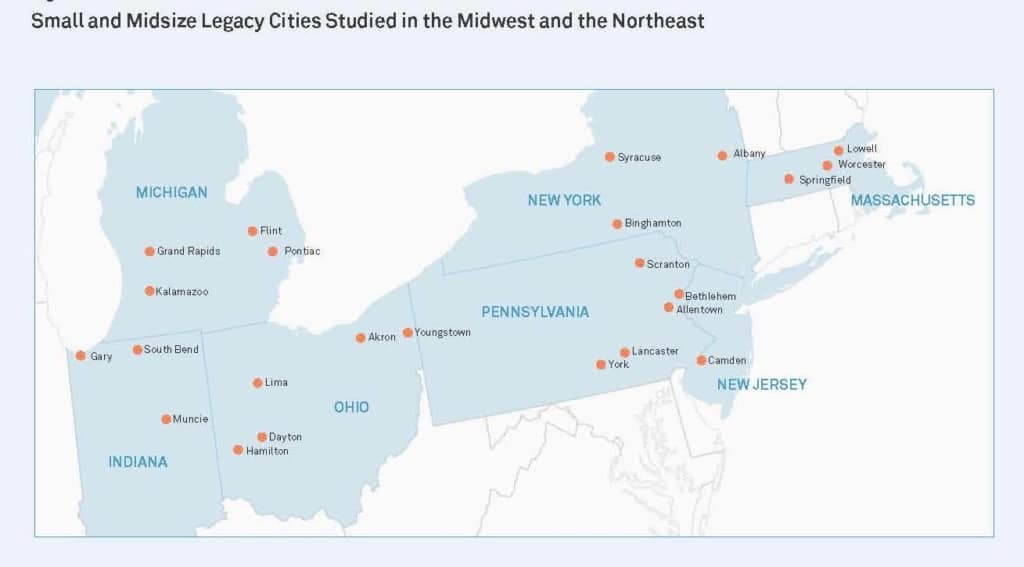

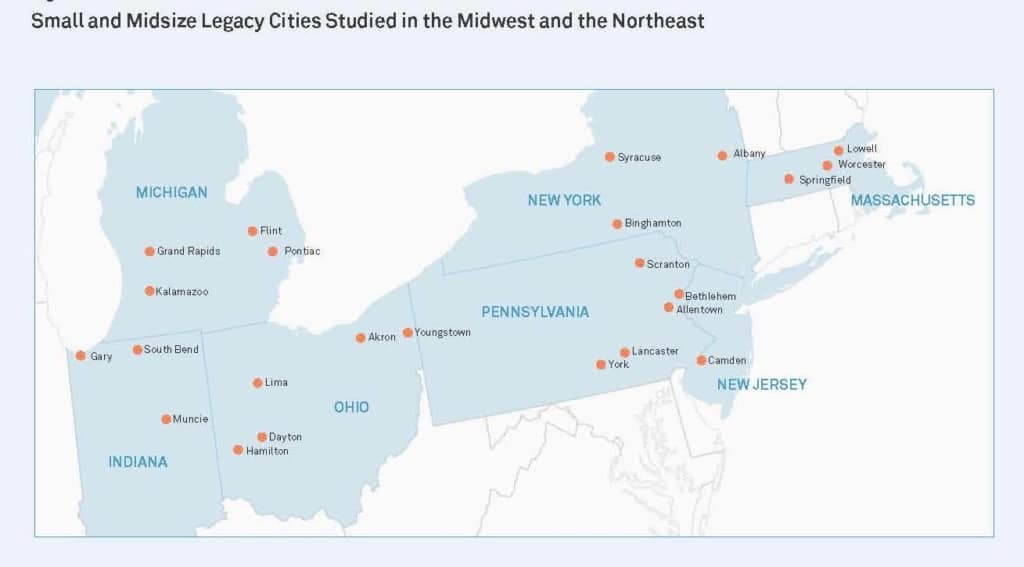

“Legacy Cities” is a term given to older, industrial urban areas—mainly in the Northeast and Midwest—that are struggling based on a variety of social science metrics. For the most part, they have seen significant population loss through the last half of the 20th century and into the 21st century. You know the names: Detroit, Dayton, Flint, Buffalo. They have higher rates of concentrated poverty and lower median household incomes. Within the United States, they are the net contributors to the population growth of the South and the Sun Belt, both because of shifts in jobs and because of weather and quality of life.

Many of these cities have significant real assets that are eroding but still remain viable and capable of revitalization. In the last 10 years, researchers, economic developers, and residents of these cities have created the Legacy City identity and have started conducting research and building communities about the future of these places. The Legacy City Partnership has a good introductory website and includes links to other reports and data. The two reports I found most useful were the original report on larger legacy cities and the companion report, published earlier this year, on Small Legacy Cities.

The Legacy City framework does not include any North Carolina cities. Legacy Cities, even small ones, tend to be larger than most cities in North Carolina. Collectively, Legacy Cities lost population in the late 20th century. While North Carolina has seen population loss during that period, most of it has been from smaller and rural areas. Of the state’s largest 38 cities with a population of more than 10,000 in 1970, only two (Kinston and Eden) lost population from 1970-2010.

Yet while the Legacy City framework does not specifically include North Carolina, it serves two useful purposes. First, it reminds us our landscape and trends are different from other places in the country. This distinctiveness is an important comparative advantage, but is also something we must monitor as other places evolve and rebound.

Second, the recent analysis, particularly of smaller Legacy Cities, provides useful lessons learned. Over the last 15 years, a playbook has emerged on how some of these cities are rebounding. North Carolina should apply those lessons and, in a hyper-competitive landscape for recruiting and maintaining employers, be aware of how the tide is changing elsewhere.

Where Are Our Legacy Cities

With the recent growth in North Carolina’s metro areas, it is easy to overstate the degree to which the state has urbanized. North Carolina is still a state with a wide collection of smaller places. Many of these places are increasingly consumed within growing metro areas, but strictly in terms of municipal political boundaries, we are still built around small towns.

Within the official Legacy City framework, the smallest cities have at least 100,000 people. As of the 2010 census, North Carolina only had nine cities of that size. Out of a population of 9.5 million in 2010, only one-third lived in cities with more than 20,000 people.

Furthermore, within our larger cities there is a wide range of sizes and characteristics. In 2010, the population of Charlotte (731,424) was 81 percent larger than Raleigh (403,892). Raleigh was 33 percent larger than Greensboro (269,666).

Greensboro, Winston-Salem, Durham and Fayetteville each contained between 200,000 and 270,000 people. Wilmington and High Point both had around 105,000 people, making them almost 600 percent smaller than Charlotte, 300 percent smaller than Raleigh and 100 percent smaller than Fayetteville and Durham. Despite this variation in size, since 1970, each of these largest cities has grown by at least 40 percent.

| Population in 2010 | # of NC Cities |

| >500,000 people | 1 |

| 400,000 – 499,999 | 1 |

| 300,000 – 399,999 | 0 |

| 200,000 – 299,999 | 4 |

| 100,000 – 199,999 | 3 |

| 50,000 – 99,999 | 8 |

| 20,000 – 49,999 | 26 |

| 10,000 – 19,999 | 39 |

| 5,000 – 9,999 | 50 |

| 1,000 – 4,999 | 202 |

| <1,000 people | 223 |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

In North Carolina, our equivalent of legacy cities are much smaller in size. Their legacy is being the hub of agricultural processing and commerce within larger rural areas. As the agricultural landscape around them has shifted, these places have been outside the growth of the rest of the state.

By way of context, in 1970, North Carolina consisted of 38 cities with a population of more than 10,000 people and 19 cities with more than 20,000 people. Between 1970 and 2010, the average growth of those cities was 92 percent.

Our legacy cities are those that are in the lowest quartile for growth during that 40-year period. Collectively, they averaged 13 percent growth—well below their peers in 1970. That would include two cities with more than 20,000 people (Kinston and Statesville) and eight cities with between 10,000 and 20,000 people (Eden, Reidsville, Lexington, Henderson, Roanoke Rapids, Lenoir, Morganton and Shelby.)

| City | 1970 pop. | 2010 pop. | Growth | City | 1970 pop. | 2010 pop. | Growth |

| Kinston | 23,020 | 21,677 | -6% | Wilson | 29,347 | 49,167 | 68% |

| Eden | 15,871 | 15,527 | -2% | Rocky Mount | 34,284 | 57,685 | 68% |

| Reidsville | 13,636 | 14,520 | 6% | Winston-Salem | 133,683 | 229,617 | 72% |

| Lexington | 17,205 | 18,931 | 10% | Thomasville | 15,230 | 26,757 | 76% |

| Henderson | 13,896 | 15,368 | 11% | Greensboro | 144,076 | 269,666 | 87% |

| Roanoke Rapids | 13,508 | 15,754 | 17% | Hickory | 20,569 | 40,010 | 95% |

| Statesville | 20,007 | 24,532 | 23% | New Bern | 14,660 | 29,524 | 101% |

| Lenoir | 14,705 | 18,228 | 24% | Chapel Hill | 26,199 | 57,233 | 118% |

| Morganton | 13,625 | 16,918 | 24% | Wilmington | 46,169 | 106,476 | 131% |

| Shelby | 16,328 | 20,323 | 24% | Asheboro | 10,797 | 25,012 | 132% |

| Lumberton | 16,961 | 21,542 | 27% | Durham | 95,438 | 228,330 | 139% |

| Elizabeth City | 14,381 | 18,683 | 30% | Sanford | 11,716 | 28,094 | 140% |

| Goldsboro | 26,960 | 36,437 | 35% | Monroe | 11,282 | 32,797 | 191% |

| Burlington | 35,930 | 50,042 | 39% | Greenville | 29,063 | 84,554 | 191% |

| Albemarle | 11,126 | 15,903 | 43% | Charlotte | 241,420 | 731,424 | 203% |

| Asheville | 57,929 | 83,393 | 44% | Raleigh | 122,830 | 403,892 | 229% |

| Salisbury | 22,515 | 33,662 | 50% | Fayetteville | 53,510 | 200,564 | 275% |

| Gastonia | 47,322 | 71,741 | 52% | Concord | 18,464 | 79,066 | 328% |

| High Point | 63,229 | 104,371 | 65% | Jacksonville | 16,289 | 70,145 | 331% |

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Like the Legacy Cities in Northeast and Midwest, all of these cities have endured significant industry loss from the state’s big three industries: tobacco (Kinston, Reidsville, and Henderson), textiles (Statesville, Roanoke Rapids, Lexington, Henderson Eden, and Shelby) and furniture (Lenoir, Morganton and Lexington). In addition, they all have infrastructure and built environments that thrived during much of the 20th century.

Importing the Framework

The Legacy Cities framework focuses on accepting modern reality, identifying specific strengths and using those to frame the future. It focuses on the opportunity to rebuild and not the decay. The researchers driving the initiative collected a wide range of information between communities in order find trends and build a comparative framework. They focused on economic, and demographic characteristics, and from that data, they create a scorecard to group cities into high-, medium- and low-performing groupings and showed scores at three points (2000, 2009, and 2015) over a 15-year period.

Grand Rapids, MI, Worcester, MA, and Lowell, MA were ranked one, two and three throughout the 15 years. Beyond that, there was movement in the rankings over the study period. One of the most telling findings was that the cities listed as high-performing across the period collectively saw a population increase of five percent from 2009-2015 after seeing a population loss of one percent from 2000-2009. As one might expect, the low-performing cities lost 5 percent from 2000-2009 and an additional 7 percent from 2009-2015.

It is hard to show direct causation between the factors the study tracks and population growth, but it is safe to say that something different was happening in these high performing markets. Fortunately, the report identifies some of the differentiating factors and uses them to construct a playbook for rebuilding legacy.

Overall, there are eight strategies the Small Legacy Cities study proposes for wannabe high performers. All of them are worth considering, but three stand out as particularly applicable to North Carolina.

Build Civic Capacity and Talent

Despite the specific situation of each Legacy City, each is struggling to attract younger citizens. One strategy that the report recommends is to create local fellowship programs that draw recent graduates to work on management-level projects in local government and important local industrial sectors. The report specifically notes that cities should be aware of the tendency to look to people with local personal ties and existing loyalties when thinking about future leadership. In many cases, communities need an infusion of new leadership and energy and can use management positions as carrots to attract talent.

Build on Authentic Sense of Place

There is no doubt that jobs drive economies, but there is increasing evidence that the quality of place drives where people want to live. The location of talent, in turn, will ultimately affect where employers place jobs. It is easy to oversimplify this equation and every “jobs discussion” in a little different.

It is clear, however, that cities should understand their legacy and their assets, and understand how they connect with different population groups. Is a city well-designed for young families? Is it situated for multi-generations and attractive to younger residents who may move home to take care of aging parents? Is the culture open and welcoming to people who might relocate into a city or industrial management position.

As the Small Cities Report notes, legacy cities should not try to become hip meccas like Portland or Austin or even Raleigh. They should maximize their own, authentic draw. In North Carolina, that is tied to our rural roots. Our continued focus on small town lifestyles provides a juxtaposition against urban alternatives—a juxtaposition for which there is significant demand.

Address the Skills Gap and Expand Opportunities

Because North Carolina’s legacy cities are interwoven with surrounding rural areas—many of which are struggling economically—future growth and success must include better connections between jobs and skills.

North Carolina has a history of developing successful workforce development programs. Indeed, a cross-state survey yields a variety of industry-based and community college-based interventions that work in specific areas. Too often, however, these workforce development programs exist in isolation, both because our state is large and somewhat disconnected but also because what works in Shelby may not address the needs in Roanoke Rapids.

As North Carolina’s legacy cities evolve and find their strategies, they must include community-specific responses to the skills and wealth gaps in these areas. Poverty and pronounced income disparities do not just destroy families and create blight, they ultimately become a counter weight to progress and to growth.

By many metrics, North Carolina is on a successful trajectory. The top 10 most populated cities are on best-of lists and are achieving growth that most of the country and world strives for. In reality, that trajectory is more limited. Our history and our present is tied to an identity of smaller places. We must figure out how to nurture that identity while simultaneously pushing the boundaries of growth in our metro areas.

This is our challenge, and our legacy cities have an important role in determining our level of success.