Share this story

- North Carolina’s Migrant Education Program can provide a slew of academic and supportive services to young workers or children whose families have recently migrated to the state to work in agriculture and fishing.

- These programs help migratory students overcome “the obstacles created by frequent moves, educational disruption, cultural and language differences, and health-related problems.”

|

|

Every year, thousands of men, women, and children travel to North Carolina in search of work in agriculture or fishing. Many are school-aged children who have opted to work for a season — or year-round — or families with school-aged children.

When harvest and fishing seasons wrap up, they might move on to other states. But while they are living in North Carolina, these children may be eligible to receive a wide range of academic and social support services through the Migrant Education Program (MEP).

What is the Migrant Education Program? And who is eligible?

The federally funded program, created as part of Title 1 of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) in 1965, helps migratory students “meet high academic challenges by overcoming the obstacles created by frequent moves, educational disruption, cultural and language differences, and health-related problems,” according to the state Department of Public Instruction’s (DPI) website.

These services are supplemental to any state, local, or other federal funds that are being provided to students in their school district.

“The whole purpose of a migrant program is to provide supplemental services to those students. So they would have access to Title 1 funding or whatever funds are there,” Dr. LaTricia Townsend, director of federal program monitoring and support at DPI, said. “It is the cherry on the top. It is not your baseline. It is what you would get in addition to — it’s a layer of support that you’re getting.”

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

The program does not guarantee services to all students who have moved to North Carolina from another state or country. Rather, eligible students must meet the following criteria:

- They are ages 3-21.

- They have not yet received a high school diploma or its equivalent.

- They have moved into a school district within the last 36 months.

- Either their parents, guardians, spouses, or themselves must have moved due to economic necessity and have worked in agricultural production or fishing within the last 36 months.

On average, North Carolina has 4,800 to 5,100 students enrolled in a MEP, said Dr. Heriberto Corral, DPI’s MEP data and parent engagement coordinator.

What services can students receive?

Services within a program can be split into two fields: instructional services and supportive services.

Instructional services

For preschool students, MEP recruiters can help families enroll their child in a formalized preschool program in their district or can assign a tutor to provide a minimum 18 hours of instruction per school year or throughout the summer.

For older children, the main academic goal of the program is for them to receive a high school diploma, said Juan Carlos Alvarez, who oversees the identification and recruitment of students to the program at DPI.

K-12 students may receive additional tutoring services on top of what is offered to students attending their school. Districts with standalone programs might also provide summer programs tailored to migratory students.

During the summer, North Carolina sees a “huge influx” of out-of-school youth — those who are not enrolled in a district but are eligible to receive services through a MEP, Corral said. These students, for example, may receive English tutoring or might be connected to high school equivalency programs to obtain their diploma.

Supportive services

Supportive services are geared towards ensuring that the needs of migratory families and youth are met so they can fully participate in their education, said Hunter Ogletree, DPI’s MEP compliance coordinator. That means the range of services is extensive.

“If a child doesn’t have a mattress to sleep on at night because his or her family just moved to North Carolina from Florida, in a small car and didn’t have room to bring a mattress, then a supportive service could be accessing a mattress for that child so that he or she can be well rested to participate fully in school the next day,” Ogletree said.

Alvarez offered the example of helping a student get glasses if their family can’t afford them. Recruiters might reach out to an eye doctor to ask about discounts, speak with a school nurse about programs to get free glasses, or might use federal funds to pay for the glasses.

Additional support services can include assistance with transportation, interpretation — including, for example, to schedule doctor appointments — and advocating for the family or the child. Recruiters have also arranged classes for migratory students on how to navigate daily life in North Carolina. Those have included lessons on how to order food at a restaurant, get an ID, or open a bank account.

Who should students and families contact to join an MEP?

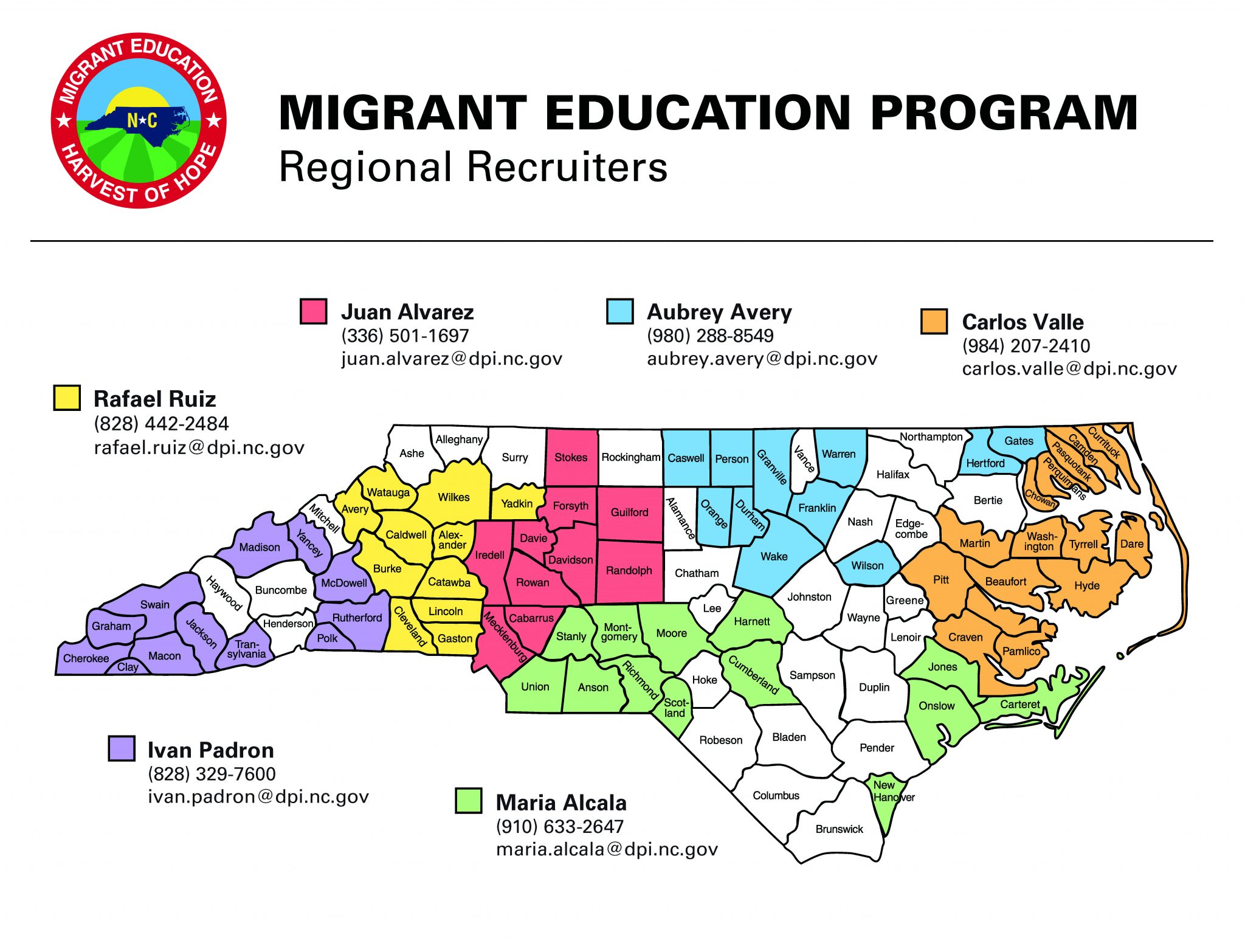

Thirty-one North Carolina school districts have their own standalone program — these receive federal funding through DPI but are administered by district officials. All other districts are overseen by one of DPI’s regional recruiters, who travel between districts in their region to ensure students are receiving the services they need.

Click on your district to find additional information about its MEP:

Students in Clinton City Schools who are eligible to join an MEP can receive benefits through Sampson County Schools, said William Vann, director of special programs at Clinton City Schools. Students in Columbus, Greene, and Halifax counties, as well as Whiteville City Schools, should contact their district to get additional information about their local MEP.

Once a district identifies at least 50 migrant students, leaders can decide to start an MEP but are not required to do so, Alvarez said.

“We are in communication with the largest districts and look forward at the possibility of starting their own standalone program,” Alvarez said.

What if the student will only be in North Carolina for a brief time?

Eligible children can receive services regardless of how long they’ll be in North Carolina.

Townsend said MEPs are not required to serve a student if he or she has graduated high school, turned 22 years old, or moved to another state (or district, if being served by a standalone program). Also, students may no longer receive services if their “eligibility expired 3 years after the enrollment in the program and without a new qualifying move which would reset the clock for another 3 years,” Townsend said in an emailed statement.

If a student is leaving North Carolina to work in another state, their program’s district or regional recruiter can inform that state’s MEP that a student is headed their way using a federal database known as the Migrant Student Information Exchange (MSIX).

Through MSIX, states can “ensure the appropriate enrollment, placement, and accrual of credits for migrant children nationwide,” according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Townsend said information shared through MSIX is “completely confidential and protected by FERPA (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act).”

How are students recruited for the program?

Children and families can reach out directly to their district or regional MEP recruiter for information, Alvarez said.

But when Alvarez was a recruiter for Bladen County’s program, he said, the recruitment process was far more involved and required a deep connection with the community.

It began, he said, by understanding which crops were harvested in his county and when most workers would arrive. Then, he’d find schools where young workers or children traveling with workers were enrolling. He’d find thrift stores, grocery stores, Latinx-owned businesses, even laundromats around those schools to post fliers or speak to people.

These are methods recruiters still use today, Alvarez said.

Recruiters have also relied on an occupational survey developed by DPI to identify farm-working families enrolling students in North Carolina schools. So far, the survey has been optional, but it will become mandatory in the upcoming 2022-23 school year, Corral said.

Alvarez said recruiters also work with local farm owners or growers’ associations to be notified when workers arrive in the state.

When recruiters find workers or children interested in the program, they fill out a certificate of eligibility to determine if the individual can receive services. The form does not require a Social Security number or proof of citizenship to be eligible.

Alvarez said the information provided to recruiters is completely confidential under the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and cannot be shared unless requested by a judge.

“If you feel like you might qualify, we want to talk to you to see if you’re eligible,” Ogletree said. “And then you will be able to take advantage of all of these high-quality services that we offer.”

Recommended reading