When my boss, Mebane Rash, sent me the 2014-15 salary schedules and told me to look at principal pay, my first reaction was to think I must not understand. Surely a principal overseeing 101 or more teachers wouldn’t have to wait until his or her 24th year before getting a salary bump.

My reaction became all the more familiar as I started looking into it. Many of the people I called said I must be mistaken. These were people who, I assumed, understood such matters better than me. But while they thought I had made a mistake, they couldn’t explain how. Still, I expected that any day, I would talk to someone who would be able to show me just exactly how I had gone astray.

That day never arrived. Instead, one day, I was talking to a member of the Department of Public Instruction who said he needed to check on it. I expected the return phone call to be the end of the article. Instead, he said that my understanding was accurate. It was the beginning of a long process.

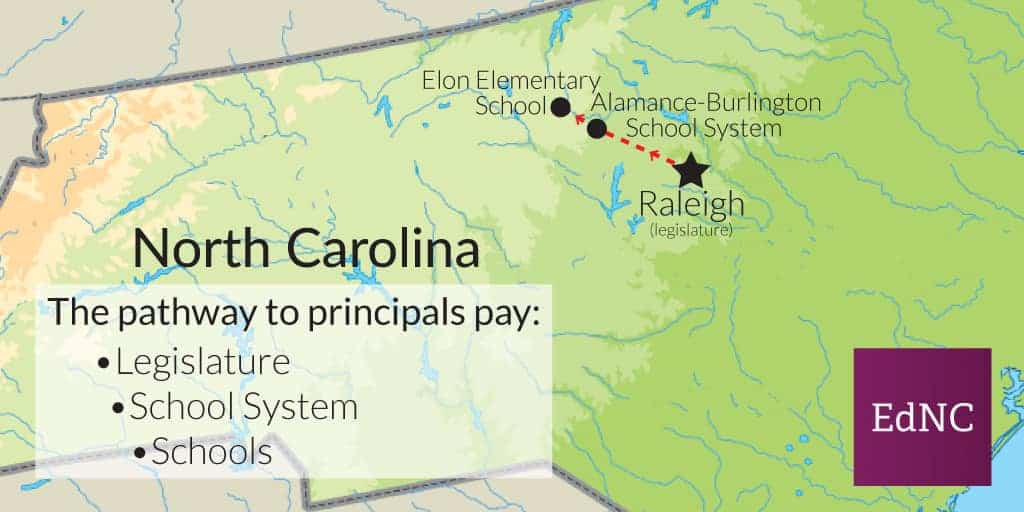

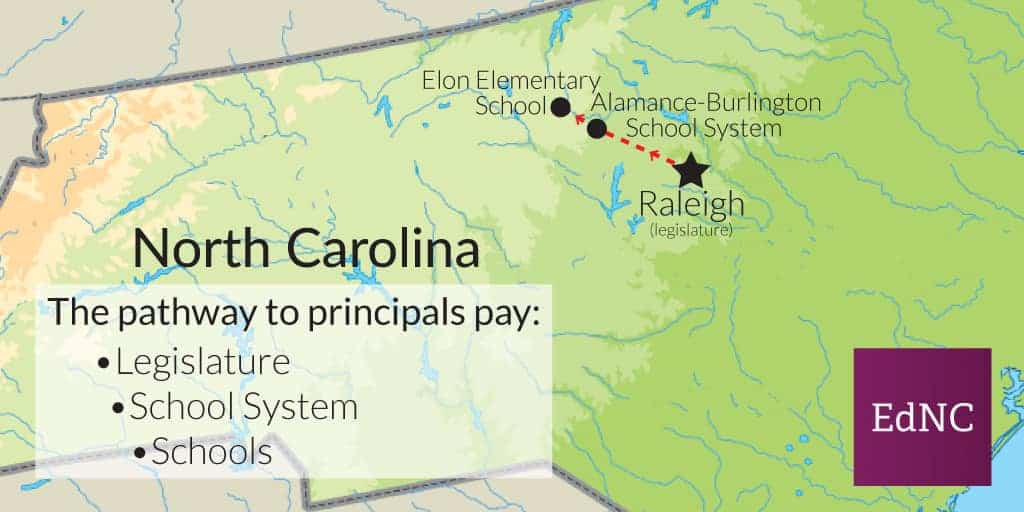

In trying to understand principal pay in North Carolina, I delved into the labyrinth of North Carolina education. It’s one that twists and turns through the halls of the General Assembly, weaves from the boardroom of the State Board of Education to local boardrooms across the state, and ultimately leads into the school buildings and classrooms where the state’s children go to learn.

My investigation also took me to other states, where I explored how other school systems apportioned compensation to their administrators. I could not find a system in any state surrounding North Carolina that had a salary schedule that looked quite like ours. I asked one official in a school district in Virginia if she had heard anything like the wait times I had found here. She said she had not.

When I first started this project, I thought it would be focused solely on the duration of waits for salary raises, but again, as I looked, I found other avenues to explore. The ability of some principals to negotiate salary increases while others had to stick with what the state and local districts could afford. The nuances of turnover rates and how different numbers manifest depending on what data you put into them. I wondered along the way how anybody could navigate this maze without the time and financial backing I was being given by my employer. I still do.

But there was one group for whom none of this was foreign — the principals.

Again and again, I heard frustration in the voices of people who had given their time and service to the state, and who couldn’t understand why their recompense came in such odd and circuitous ways. One principal told me he learned after starting in one district that other principals had been able to negotiate their pay. He hadn’t, but if he had known it was an option, he probably would have tried to. Another principal told me how going from teacher to principal had been a step down in pay at first.

They worried that complaining about their own situations would make it that much harder for teachers. So, they mostly remained silent.

I was surprised that none of this had been part of the public discussion on education sooner, but the more I talked to people, the more I understood why. The principals had been concerned about teacher pay. They wanted to make sure the people they supervised were taken care of. They worried that complaining about their own situations would make it that much harder for teachers. So, they mostly remained silent.

The one thing I never encountered in the process of researching this article was anybody who thought principal pay or turnover weren’t serious issues that needed to be addressed. Nobody told me that everything was fine and nothing needed to happen. Everybody seemed concerned about education and had ideas about how to make it better.

Going into the next General Assembly session, it’s encouraging to know that the people I face will not be divided into the “good” and “bad” variety, but rather a whole of good intentions, all seeking to find the best solution as they see fit. My takeaway from this project was that the battle for quality education in North Carolina is not over. Last session’s pay raises for teachers wasn’t the final bell of victory. It was the starting gun. And I’m eager to see the next leg of the race play out in the halls of the state legislature.