Four weeks before school let out last spring, Melissa Blum, a kindergarten teacher at Highland Elementary in Burlington, started meeting with parents of kindergartners starting school this fall. Blum wants to smooth a transition that research says is critical to the success of the school year for students, teachers, and parents.

“All of it is very overwhelming for parents,” Blum said. “There’s a lot that they need to know and have accomplished before day one.”

Blum, like most kindergarten teachers, knows that some preparation before the first day of school makes a big difference. About half of her students, she estimates, go to a formal preschool setting. Highland Elementary is one of a handful out of the district’s 20 elementary schools without a pre-K class within the school building. For students who have not left home before kindergarten, the first days of kindergarten can be filled with crying from separation anxiety and struggles to get along with other children or follow basic directions.

“We can’t really move onto the academics and the curriculum until we have those things down, and so if every child could have a boot camp to sort of practice those skills before we start, we could really hit the ground running,” Blum said.

Research says the transition into kindergarten makes a difference. Introducing a study on kindergarten transition practices, researchers from The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Maryland wrote, “The ability of students to fully engage in and benefit from their kindergarten experiences has been shown to depend on the degree to which they successfully transition into kindergarten…”

Along with several parent sessions using bits of the Ready Freddy program from the University of Pittsburgh Office of Child Development, Blum also facilitates a kindergarten readiness boot camp for two weeks in August. The sessions answer parents’ questions and expose them to content children should already know or will learn throughout the year. Then, the boot camp gives children a glimpse into what school will be like. Blum said parents know when they sign up that it’s a two-for-one package. Smoothing out this transition and making sure children have strong starts to their educational journeys is important for future success as well.

“If they’re ready for kindergarten, they tend to have better outcomes on third grade reading achievement, and third grade reading achievement predicts graduation rates, which affects our community and our economy,” Blum said. “So it all starts at birth. You can make a greater impact the younger they are.”

A kindergarten teacher’s idea

Two years ago, Blum attended Alamance County’s Teacher Leadership Academy, a nine-month program put on by the school district and a variety of community partners: Impact Alamance, the Alamance County Chamber of Commerce, Elon University, and Alamance Community College. Teachers spend time learning from local businesses and are encouraged to apply for an Impact Alamance grant to address an issue they see in the classroom.

“I knew I wanted to do something related to the transition to kindergarten,” Blum said.

Blum thought both of the children who come to kindergarten straight from home but also those who go to a formal setting that does not focus on academic foundations children will need going into kindergarten.

“Some of them are wonderful and they align really well to kindergarten goals, and some of them, they may have been involved in the program for four years but they’ve not really done the right things,” Blum said.

Impact Alamance funded the first year of the program, including a set of 40 iPads Blum uses for camp and during the school year. Following the first year, Blum was invited to attend Impact Alamance’s annual Community Transformation Council meeting, where leaders from across sectors move community goals forward. Blum shared her story and left with a connection to the Duke Community Foundation, which decided to fund the program the next year. Transportation is free for children whose parents are working or who want to get used to riding the bus before school starts.

A portion of Ready Freddy called K-Club is how Blum forms the parent sessions. The camp for children, which has served around 20 children each year, she designed on her own.

“The camp is just kind of my own thing. I just decided how I wanted to run it and what I wanted to include,” Blum said.

As Sarah Sakai’s youngest of four children started to think about kindergarten, she said he had a tons of questions: “What do you mean you’re just going to leave me? I can’t go to sleep if I’m tired? What do you mean I have to ask someone to go to the bathroom?” Sakai was concerned her son was more anxious than her other children were during this transition.

“He had a million questions, some of which couldn’t be answered just with words,” she said. “He needed to do it, to see it.”

As soon as Sakai heard of the boot camp, she signed up.

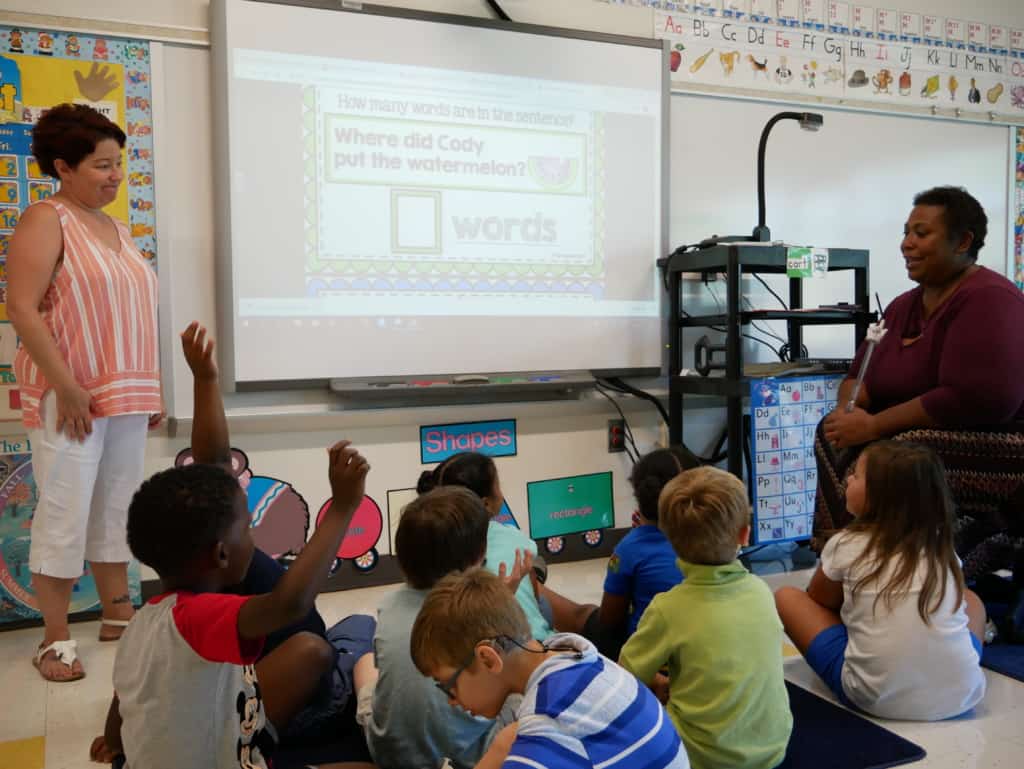

The half-day starts with fine motor activities that children can work on in groups. Once everyone arrives, the children split into three groups and start literacy activities. They learn about print concepts like what a word, letter, and sentence is, and phonological awareness, like rhyming words and listening for sounds in words. Students also work on identifying, spelling, and writing their names. Then comes recess, followed by some time on an educational program on iPads and an interactive smart board activity on phonological awareness. Math skills are last, which include identifying numbers one through 10 and counting sets of objects.

About half of the children who attend the boot camp will actually attend Highland Elementary. The rest will go to kindergarten at another elementary school in the Alamance-Burlington School System (ABSS). Keira Klein Anderson, whose son attended the boot camp but started kindergarten this week at Elon Elementary, said he benefited from simply being in a school building for the first time.

“I don’t think he’d ever been in a full school-sized classroom — so that was another thing, having that experience, being in an elementary school, in a classroom, going into the library, ” Anderson said. She said she worried her son would struggle in going from around nine hours of preschool a week, to a summer staying at home, to full days of kindergarten.

“It just was the perfect bridge from what he’d done in preschool, then to have a little warm-up, then settling in this week to kindergarten,” she said. “I think he really was ready for it.”

Parent camaraderie

The parent sessions dive into transportation, school information and communication, after-school care, and the kindergarten curriculum. Blum and other teachers give parents activities to start working on at home, both for before the school year and throughout it.

“We show them how to find their school information on the ABSS website, the kindergarten health assessment, immunizations, school supplies, thinking through transportation, after-school care,” Blum said. “We touch on all those topics that they’re going to need to be thinking about and answer their questions.”

Many parents are surprised, Blum said, at what students are expected to know by the end of the year.

“I tell them, ‘It’s going to be okay,'” Blum said. “We do a little bit at a time, and we build upon what we’ve done, and it looks like they’re really required to do a lot but at this age they’re excited and they’re sponges. They learn so quickly, and they want to learn. So we’re really able to do a lot with them.”

Parents Anderson and Sakai had met briefly before at a play date for their children but got to know each other from the Ready Freddy sessions. Blum said she has seen these types of relationships form.

“I think it’s a nice way for them to build camaraderie with other parents who are going through the same thing so they can talk about it together and share those anxieties and questions and answers with each other,” she said.

Even though she is a former elementary educator, Sakai said she learned valuable bits of information she wouldn’t have known if it weren’t for the Ready Freddy parent sessions. One tip she has used since with all of her children is, when a child asks you how to spell something, not immediately spelling it out for them. Instead, Sakai learned to ask them what letters they hear in the word and ask them to work through the word together.

“When you spell for them… you’re taking away their ability to learn how to space that word out,” Sakai said. “… I have a degree in education and I have a second grader and I would spell words for him, for both of them. And now it really has changed my mindset on how I approach their writing and their reading because they really have to learn to be patient.”

Sakai also learned of differences between the curriculum at her son’s preschool and the expectations of kindergarten. Her son had learned to write his name in all uppercase letters. The parent sessions warned her of this and other discrepancies to start working on at home.

“I’m having to reteach my child the way it’s supposed to be in public school,” she said. She also said that it was hard as a parent to know what to expect from preschool and what her child should be learning.

“I really wish the state had a little more regularity with that,” Sakai said.

As students across the state start kindergarten, the transition into the first year of required school looks different in different areas. Some parents attend open houses and orientations, some preschool teachers share information with kindergarten teachers, and some children attend preparation summer camps like Blum’s. Next week, we’ll look at how the state is piloting transition tool kits for communities and increasing communication between preschools and public schools.

Recommended reading