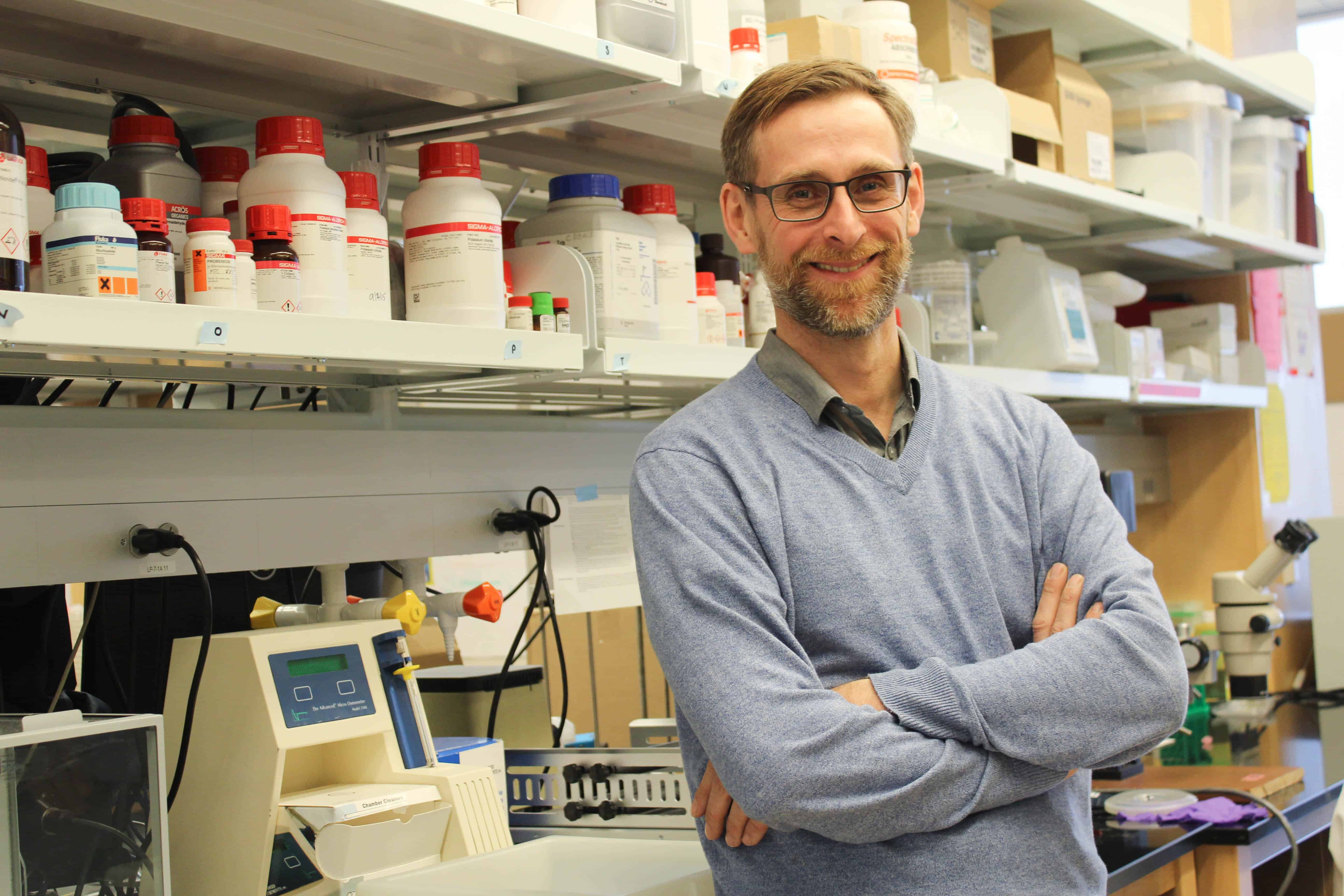

On Friday, I visited the Marsico Lung Institute at UNC-Chapel Hill to speak with Associate Professor Robert Tarran about his team’s e-cigarette research and get a look inside the lab.

Their research focuses on the organs into which vapers are inhaling e-cig aerosols: the lungs. We dove into the limitations of vaping studies, their most surprising e-cig study findings to date, and what Tarran would like vapers to know about the products they’re using.

Here are some key take-aways:

- There have been studies on how nicotine affects the adolescent brain, which is still developing. The lungs are still developing, too, but this hasn’t been well studied.

- Lung researchers like Tarran are finding changes in the lungs due to vaping, including changes in lung lining, a fluid needed to keep the lungs clean and healthy. Abnormal lung lining fluid can cause lung disease.

- Researchers have found an increase in proteases in vaper’s lungs. According to Tarran, “Your proteases are proteins that cut other proteins” and proteases are known to cause lung disease by literally degrading the lungs.

- Long-term studies are needed to know the full effects of vaping overtime, however, Tarran says his team is already seeing large biological effects to the lungs.

Read on for more from the interview, edited for length and clarity.

Bendaas: So you’re in year two of five of your current project. Can you give me some insight into what you’re working on?

Tarran: We’re funded just to look at the effects of nicotine. There’s a lot of papers on tobacco smoke exposure, and it’s the whole smoke — it’s the nicotine, the tar, the noxious gases. And so they haven’t sorted out the effects. There’s another study of people [with] e-cigarettes, but the NIH (National Institutes of Health) figured there was a knowledge gap with nicotine, so they wanted to study just the effects of that.

Bendaas: Are you looking at certain age groups? Are you looking at adolescents since adolescents are [vaping]?

Tarran: So for us, it’s just easier to do over 18. Young adults. By the nature, because most of the stuff we’re doing is healthy people, they tend to be younger age — probably early 20s is what we’re studying right now. I think adolescence is interesting because the brain is still developing. Actually, the lung is still developing. The lung, if you go from say a 12-year-old to a 20-year-old, I mean the lung develops a lot. There’s a reason why, if you think about the Tour de France, there’s a reason why most people win at like 30.

Bendaas: Is it the lung capacity that’s developing?

Tarran: No, the branches. Even from a 12-year-old to a 16-year-old, the number of branches is still growing because think about the size of someone’s chest as a 12-year-old boy versus me. Your chest is bigger so you get a lot more branches. And it’s not really been studied how [much] tobacco products, e-cigarettes, Juul, affect the development of the lung.

Bendaas: I was also asking because with the nicotine aspect, I’ve spoken to some folks who say that they’ve noticed a change in behavior in their children when they are hooked on it earlier, so 14, 15 versus 18.

Tarran: That’s been published that nicotine actually affects development of the brain. It actually changes the way the brain lays down its [synapses].

Bendaas: You here are really focused on what’s going on with the lungs. I also saw that you all did a study on third-hand [vape exposure] with the vapor sitting on surfaces?

Tarran: E-cigarette fluids are fluorescent, which is useful for [studying] exposure. We published it saying this could be used for third-hand, but for us … we do studies with people, and we do studies in the lab on lung cells. In the lab, you can expose lung cells to e-cig vapor. We wanted to see if this vapor can actually get inside cells, where it might affect cellular functions.

One of the things we’ve done and we’re still doing is you can pick a certain thing like, “I’m going to study protein A and just study that protein in detail” … to get information about a protein, but with modern technology you can do genomics. … Gene expression changes how much protein is made, whether it gets made, and what gene gets turned on in development, gets turned off, etc., etc. You can study one gene at a time … but now they have these things where you can study thousands of genes at once. So genomics is the study of thousands of genes. For example, you can get your lung cells, run them over, and then study 10,000 genes at once and then look at the changes.

We’re comparing vapers to smokers to non-smokers. It’s kind of like a cross-sectional approach. The reason that we chose that approach is, if you don’t know what vaping does — rather than just pick your particular protein … well, we’re going to be agnostic. There’s less bias in it. You can just say, ‘We’re going to look at cells from vapers and capture as much information as we can and see what changes.’ So that’s been our approach.

My lab had a paper out. We did proteomics (study of a set of proteins) on … lung lining cells, and they saw a lot of changes. The group just down the hall had [a study] — Boris Reidel was the lead author — where they measured sputum, the lung lining fluid. And again, they actually found more changes in vapers than smokers.

Bendaas: In terms of the lung lining? Why do you think that is?

Tarran: So something in the e-cigarette smoke is changing the lung environment, and that’s being reflected.

It’s interesting — well interesting to me — you and I have about a teaspoon of salty liquid which lines the entire surface area of your lung. And the lung has a surface area the size of a tennis court.

And that one teaspoon of liquid is spread over that whole area, but that liquid is actually really important for keeping your lungs wet and clean. This liquid is constantly being produced … it has mucus, it has antimicrobial peptides in it, it has anti-inflammatory cells. … So that liquid even though it’s very small, it’s really important. Looking at changes in that liquid, the guys down the hallway they found the mucin — in COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease) mucous kind of clogs up your lungs — they found similar mucins weren’t regulated in vaping.

Bendaas: There is a pulmonologist I talked to who said you could see some asthmatic or COPD-like symptoms over time [with vaping].

Tarran: We’re definitely seeing COPD-like stuff. One of the things we’re doing now, based on their paper, they thought there’s more proteases in the lungs of vapers. Your proteases are proteins that cut other proteins. They’re kind of like molecular scissors. … It’s known that proteases cause lung disease. In cystic fibrosis, which is a genetic disease, because of the chronic infections, proteases go up and they chew up the lung. The same thing in COPD and emphysema —proteases are up and they chew up the lungs. They found evidence of proteases being increased in vapers’ lungs.

… If vaping was kind of harm reduction, that’d be great. But at least from a lung perspective, we’re not seeing that.

Bendaas: You’re right. The vape companies are promoting it as a cessation tool that’s safer. But you’re saying, from the lung perspective in terms of research, it’s not?

Tarran: There’s one paper that came out last year or the year before where they studied vapers over a couple years and measured their lung function and they didn’t see any change so they concluded that [vaping] was safer. But they didn’t do a smoking control group, and you know, healthy smokers have normal lung function, too, because it takes awhile for lung function to change.

Bendaas: For a lot of [the studies] … they haven’t been able to do them long-term. Can you explain more about [the implications of] that?

Tarran: Imagine you have a 21-year-old who decides to start smoking. By the time [he’s] 30, [his] lung function would be normal. There would be changes going on in the lungs. … Most reliable measures of lung function are actually measures of large airways, whereas the alveoli (air sacs at the end of the respiratory tree) … it’s really hard to measure lung function there. … So if you do clinical trials, you just do a measure of large airway, but it’s not super sensitive…

[Through] CT scans, you can pick up changes before you see changes in lung function. … If you’re [looking at] 40-year-old healthy smokers and do CT scans, you’d see changes in the structure of their lungs even though they have normal lung function.Bendaas: I hadn’t thought of it that way … that the main airways might still be fine.

Tarran: It’s also that the measures we have measure the large airway. You have one trachea and two bronchi, and then it keeps doubling down. There’s actually 600 million alveoli in the lung, only one trachea. So if you’re measuring just the large airway clearance, which is the big tubes, it’s fine. … It takes a lot of changes in the small airways to impact large airway clearance.

Bendaas: So in terms of vaping, what are the impacts to the smaller airways and to the fluids?

Tarran: You can’t get a probe down to directly take samples from the very, very small airways. The technology isn’t there, but you speculate there may be changes. I know some colleagues of mine in New York vaped mice for four months, and they found it caused emphysema.

Bendaas: What other research is going on here at UNC?

Tarran: We collected this cohort of patients through TCORS, and we’re still working through those. We have lung samples — we actually have blood samples — to look for changes and see if there’s systemic changes as well. … One of the things with the TCORS study, when we started recruitment, a lot of the vapers were ex-smokers, so there’s always that question: Is it due to ex-smoking, or is it due to the current vaping? Now, seven years later, you can find people who vape who have never smoked, so we’re gearing up trying to do another study where we collect airway secretions and airway immune cells and just look at this in vapers who have never smoked to make it a cleaner study.

…We’re also [working] in the lab. One of the things we want to do is — from these airway samples, because the lung lining fluid plays an important role in keeping your lungs clean — we can actually take that lung lining fluid and see if it can kill bacteria like it’s supposed to. … We can kind of interrogate it to look at the functionality of that [fluid]. We want to do those types of studies. Part of that, like I said, is just chugging through the samples that we have. It just takes awhile.

Bendaas: So that’s a possible future study.

Tarran: Future studies would be to look and see if the lung defense is impaired in secretions from vapers.

Bendaas: Have you been looking at all this mostly since 2012? Was that your first big look at e-cigs?

Tarran: We got funded in 2013, so five years, six years now.

Bendaas: That’s still a good amount of time. What would you say is the most surprising thing that you’ve found?

Tarran: To me, I think the surprising thing is — one, we are seeing changes. I’m still surprised at that. And two, that there’s some similarities with smoking, but also a lot of differences. Those things together I think are both surprising.

The British government said that vaping’s 95 percent safer than smoking. The panel that made that determination were not pulmonologists or biologists. They were psychiatrists who do behavioral studies. What they did was they counted the number of known cancer causing chemicals of e-cigarettes versus the potential number of chemicals in cigarettes and divided them and that’s how they got the 95 percent number. It wasn’t based on any clinical trials or any data. …When you first look at [vaping], it should be safer because there’s less chemicals in it. … We weren’t necessarily thinking about seeing anything. I’m surprised that we’re seeing as many changes as we are.

Bendaas: Since you’re doing the research, what do want public health officials … to know from your work?

Tarran: I would say from our work and from the work of my colleagues, basically in everything we’ve seen, vaping is not safer for the lung than smoking. … We can’t say that maybe for the heart. You know, if you’re smoking you can get bladder cancer, you can get a whole bunch of other things beyond infection of the lung. It may be better for other parts of the body; we haven’t looked. But just from the lung, which is the one thing we know, it doesn’t seem to be any better.

Bendaas: I just saw a study that said it increased your chance of stroke, so it seems it isn’t just your lungs.

Tarran: I think people need to be aware of that. My dad was a smoker. My dad is nearly 80. He said when they started smoking, back in the ’50s — he started smoking as a teenager. … Back then there were these adverts, ‘Camel recommends these cigarettes because they’re safer.’ … I mean, look seriously, I’m just googling this and there’s vintage Camel adverts. They show pictures of doctors smoking cigarettes, and you look at this …

Bendaas: Oh wow. It says,’Give your throat a vacation.’

Tarran: It essentially says, these doctors say these are better for you. And these are literally the adverts from the ’50s. So my dad was like, ‘We didn’t know it was that bad.’ And then I remember my uncles in the ’80s, they were smoking ‘low tar’ because it was implied they were safer. They think, ‘Oh, it’s okay. It’s low tar.’

So I just want people to be aware of the risk. This is what the tobacco industry has done before.

Bendaas: I’ve heard lots of comparisons between the vape industry and the tobacco industry. … I mean, Altria just bought a giant stake in Juul.

Tarran: I’ve heard that. I just think people need to be aware. You might say that if you smoke, it’s your personal choice these days. Cause if you smoke, it’s addictive, but people like it. But people now know what the risks are.

I just think people need to know if you choose to vape, it is making changes to your lung…

And yea, we need to do more science. … But as people do more and more studies, it’s going to come out. (Sidenote: Tarran has an upcoming paper with more results, though I am unable to share those results here until the paper is published.)

Bendaas: So, you all are doing a lot of neat things here.

Tarran: We’re trying.

Bendaas: How has the media response been to your studies?

Tarran: Every paper we’ve put out, the media in general have been quite interested. The last big paper we had, we screened a couple of e-liquids where we looked to see what was in them and then looked for toxicity. … Some of the comments were just ‘Oh, this is a bad study’ and ‘fake news’ and I guess some people who are [big] proponents, they like to be active…

Bendaas: It’s almost like some people don’t want to believe [your results].

Tarran: …Are we really going to know until we do it for awhile? We’re trying to look into the crystal ball and predict what’s going to happen because it takes 30 years of smoking to get full-blown lung disease. So you’re almost trying to look into your crystal ball and say, ‘What’s going to happen in the future?’

I would say the fact that you’re seeing biological effects [from vaping], which I’d say are the same magnitude [compared to smoking] but different. It’s almost like a Venn diagram where there’s some similarities but then differences.

The fact that you’re seeing … pretty large biological effects means something’s going on. And the things we have [seen in vaping] which are similar [to smoking] are things we know can be pathogenic, so increase in proteases, increase in mucins — all of those things are bad…

Bendaas: As you continue this work, what do you hope comes out of it?

Tarran: From a scientific point of view, I hope this would encourage the powers that be to fund bigger studies. … Because we’re just getting a snapshot of what’s happening in the Chapel Hill area. … I would also hope that it would encourage the FDA to regulate these things more stringently. And then from a third point of view, I hope we can give vapers a better informed choice.

Keep up with our vaping series, including updates from Dr. Tarran and his colleagues, here.