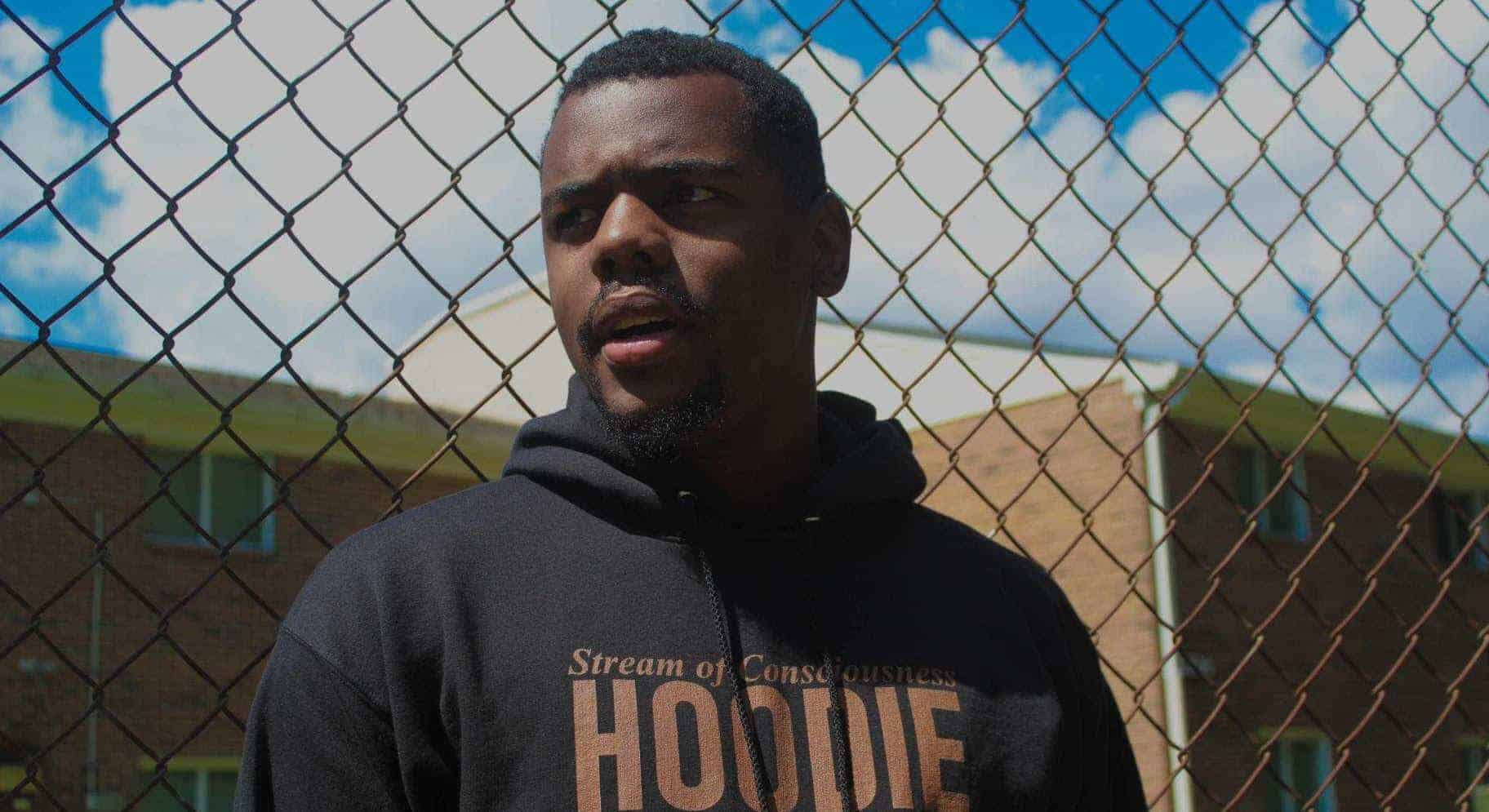

Before Derick Stephenson was a spoken-word poet, or a published author, or a teacher in rural North Carolina, he was a confused middle schooler growing up in Jacksonville, Florida. Life was hard at that age. Stephenson struggled with depression, was bullied, and didn’t feel supported.

“It’s almost like we’re ostracized during that time in our life because of the change and the growth that we’re making,” Stephenson said.

As he went off to college at Christopher Newport University in Virginia, Stephenson recalled, he knew he wanted to work with youth who were that very age — his desire driven by what he described as “an obligation to just reach back and support the people that come behind us.” Later, as an eighth-grade English teacher in Tarboro, he was constantly reminded of his own adolescence.

“I don’t know how many times I’d tell people I’m a middle school teacher and I’d hear, ‘Bless your heart,’ or, ‘I’m so sorry for you,’ when in reality that’s the time period where we need to be embraced the most,” he said.

Stephenson spent three years at Martin Millennium Academy (MMA), the first two as part of Teach for America (TFA), before leaving the teaching profession to move back to Newport News, Virginia, and support high schoolers as they transition to college.

His time in the classroom was filled with moments of joy and many of challenge. He experienced the intellectual and emotional demands that all educators face. In a rural, high-poverty district, Stephenson struggled with questions of how teachers and schools can address student trauma and create opportunity with limited resources. As the only black male teacher in a school with a predominantly black student population, he faced additional challenges.

Stephenson’s experience speaks to a larger reality in North Carolina and beyond. While more than half of students in the state’s schools are students of color, 80% of teachers are white. Spurred by research that a racial match between students and teachers improves academic success, education leaders are asking how to recruit and retain teachers of color, especially men.

“It was intimidating to step inside my school and be the only black male teacher, period — to literally be the only one,” Stephenson said. “… Initially, I felt way more connected to my students than I did to any other adult in the building.”

After a couple of months of feeling isolated, Stephenson met Leshaun Jenkins, now an assistant principal at Tarboro High School. Jenkins introduced Stephenson to Donnell Cannon, principal of North Edgecombe High School.

“For the rest of that year, there was this little trio,” he said. “We had started a book club for black men. It was just us three. I needed that brotherhood. That’s what I would call it. I needed that brotherhood that I could talk about the experiences that I was having that others might not identify with.”

Stephenson said he felt lucky to find MMA. After majoring in social work in college, Stephenson attended a TFA meeting as a favor for a friend but ended up seeing teaching as a way to better understand the lives of young people.

“In order to effectively serve youth I need to understand the education system,” he said. “If the youth I’m serving are spending a significant amount of time in the classroom, I need to be aware of it.”

TFA placed him in Edgecombe, a rural county an hour east of Raleigh, but left the school choice up to him. He said MMA stuck out because administrators there asked him about his passions and talked about several programs where they thought his skills would help. And they didn’t ask him to coach basketball, which he’d never played.

“I think as black males,” he said, “we get reduced to the influence that we can have on black boys. ‘You’re just going to be such a good role model.’ Every single interview outside of MMA, that’s all they would focus on.”

Still, Stephenson said there were stereotypes that affected his job.

“In a lot of households, the black male may be one of the most hated positions, because of the stereotype of them being absent or that type of thing,” he said. “So I not only have to remedy pre-existing notions of what it means to be a black male, but now I have to work to build a positive identity for what it means to be a black male, while still working to balance the relationships of everyone else. That blew my mind because people would undermine some of the challenges that I had because it was this assumption that everything would come easy solely because I was a black male.”

He said other teachers often would send him children with behavioral issues, which created unhealthy habits for the children and put an extra burden on top of his responsibility for the students in his class.

“It can turn into the kid … almost developing a habit of that system of like, ‘Oh, I know they’re just going to send me to Mr. Stephenson, now I’m cool with Mr. Stephenson, so I’m gonna do this so I can go into Mr. Stephenson’s class.’ That just creates that habit if they never address it themselves.”

Much of Stephenson’s first year as a teacher was spent dealing with the hardships that Hurricane Matthew brought to Tarboro, and many other towns across eastern North Carolina, in the fall of 2016. Students were out of school for weeks, and many were displaced from their homes. Matthew’s impacts played out long after the flooding left, with students staying in hotels for months and coping with the stress symptoms that traumatic events often create.

“When you break it down to the demographics versus layout of the town and you figure out some of the historical significance of why some areas were impacted more than others and why certain students have to deal with those traumas more directly than other students, that kept me up a lot that first year,” Stephenson said. “It made me feel like wanting to quit each day. I felt like I wasn’t doing enough in addressing the needs of my students.”

Stephenson found ways to talk about outside issues that were obviously affecting students in the classroom. He started each year with a gallery walk, where he raised different topics, such as growing up in a single-parent household, depression, bullying, and homelessness, asking students whether they had been affected by them. He asked students what advice they may give to someone who had been.

“My goal is for me to establish myself as somebody who can be transparent with you and can support your needs prior to forcing this academic content upon you,” he said. “At the end of the discussion, I let them know that all of the events are about my life. And that was to establish a connection between me and every single student that I stand before.”

Stephenson said he liked classroom activities that sparked students to ask questions about the world. By his second year teaching, he had found more of his groove as a teacher — and more opportunities to foster those questions. One piece of his curriculum, which he called his “caged bird series,” brought together a poem (his favorite) called “Sympathy” by Paul Laurence Dunbar, a J. Cole song called “Caged Bird,” and an Alicia Keys song and Maya Angelou poem, both with the same title.

Stephenson also would have the students construct origami birds and paper cages. Before they folded the birds together, he asked students to write all the things that make them feel free.

“If they were to imagine their best self, what would that look like?” he said.

As students finished with their birds and moved on to building their cages, he would tell them to write all the things that made them feel caged in.

“We put the bird inside the cage and I actually hung them up all over my classroom,” Stephenson said. Through the texts and their personal connections to them, students asked questions about incarceration, religion, and slavery. “That’s when teaching started to click for me,” he said. “… You can go ask kids right now. They probably don’t remember a lot of stuff. They will remember the caged bird series.”

Stephenson said he can’t quite put his finger on why he stayed for a third year past his TFA obligation. Something felt unfinished, he said. But after another year, he felt ready for a change. “I knew I was ready to grow,” he said.

Part of that decision was knowing that the environment wasn’t right for him. He loved reading essays but hated grading papers. He didn’t like being in the same room for most of the day. Although the pay was fine for just him, he didn’t want to be financially restricted in the future. He didn’t like feeling limited by parents and others who weren’t comfortable with the parts of his classrooms, like the gallery walk and caged bird series, that opened tough conversations. He knew he could do the same work with children outside the classroom without that pressure.

“I would have parents coming up to me like, ‘Why are my students talking about depression? … This is English class. Y’all need to be reading or something.”

During a trip to Washington, D.C., for a spoken-word performance, Stephenson ran into a dean at Christopher Newport University who told him he had recommended his name for a position in charge of a new program, Community Captains, that supported local students’ postsecondary transition through mentoring, college and career planning, and guaranteed admission to the university with certain requirements met.

“Everything was just kind of aligned,” Stephenson said.

He is still dedicated to supporting youth and connected to the education system in multiple ways. Apart from his job, he is working with Profound Gentlemen, a national organization based in Charlotte that aims to support male educators of color through professional development and social networks.

He said he’d like to see more people doing their part, even in small ways, in helping young people find their way. Make a connection with a local high school and use whatever expertise you have, he said. Talk about finances, or health, or your career. “I’ve seen some of the simplest gestures change a kid’s world.”

It is our responsibility, he said.

“There’s so many people who complain about the education system, but when’s the last time you stepped inside the classroom to teach them yourself?”