About this parent’s guide: The term “learning differences” covers a wide range of challenges students may face in school, at home, and in their community. It includes all children who are struggling in school because their brains are wired uniquely — whether a learning disability has been formally identified or not. This parent’s guide can be helpful for all parents of students with learning differences. However, it is designed to be particularly helpful for those with children who have, or might have, a specific learning difference or other health impairment (e.g., attention issue) as defined by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

This is Part 1 of a series of parent’s guides related to learning differences. Click here to read Part 2.

Grades can be a poor indicator that your child has a learning or attention issue. Some kids who perform well have found ways to cope, and others, who are performing poorly, may not have a learning disability. The clues, say those who work with children that have learning disabilities, are sometimes more subtle and often times unrelated to school performance.

If you’re reading this, you may already know that. But you may also be wondering what to look for when it comes to learning differences. And, if you’ve spent time online asking search engines for answers, you could be just as confused as when you began.

“Its challenging, because it’s like, where do you even start?” said Lynne Loeser, statewide consultant to the Exceptional Child Division of the Department of Public Instruction. “And how do we get this into language that is helpful and understandable to parents and not get too far into the weeds? We talk in edu-speak — a lot of vocabulary and a lot of acronyms the parents don’t understand.”

This guide is aimed at cutting through the edu-speak. In this article, Part One of our guide for parents, you’ll find some tips on how to determine if your child has a learning disability.

In Part Two, we’ll dive into the laws that provide assistance — specifically, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (504). Part Three examines data that speaks to how effectively North Carolina public schools are reaching these students, whom it calls Exceptional Children. In Part Four, we’ll look at independent schools that offer more focused instruction for different learners, as well as resources available to help finance a private education.

But, please note: This is only one resource for parents. More information is available through the public school system, Exceptional Children’s Assistance Center, which is funded through federal grants, and state and national resources such as Disability Rights North Carolina, Learning Disabilities Association of North Carolina, and Understood.org.

How do you know there’s a problem?

Tests, assessments, and homework results can be warning signs that your child needs additional support, but they can also be unreliable indicators since poor academic performance can result from a number of other factors.

“We often see one of two reactions: either the student is shutting down or the student is acting out,” said Virginia Fogg, an attorney for Disability Rights North Carolina (DRNC). “And so, basically, if you were to use psychological terms, you’re either internalizing your stress or you’re externalizing it.”

Children who are externalizing stress and anxiety from learning challenges might disrupt class, which is why, according to Fogg, they have higher rates of disciplinary issues and suspensions.

“Unfortunately, those are the kids that often get the attention,” she said. “Now, it’s often negative attention.”

Children who internalize behaviors might simply put their heads down on their desk, not open their book, disengage from group work, or stop paying attention while teachers are giving instructions.

In earlier grades, when there are not a lot of tests and homework to monitor, failing to follow directions or having trouble getting out the door could indicate processing issues. These can be exacerbated once children are in school because so many directions are given verbally. Also, trouble tying shoes or writing their names can be red flags for issues with fine motor skills.

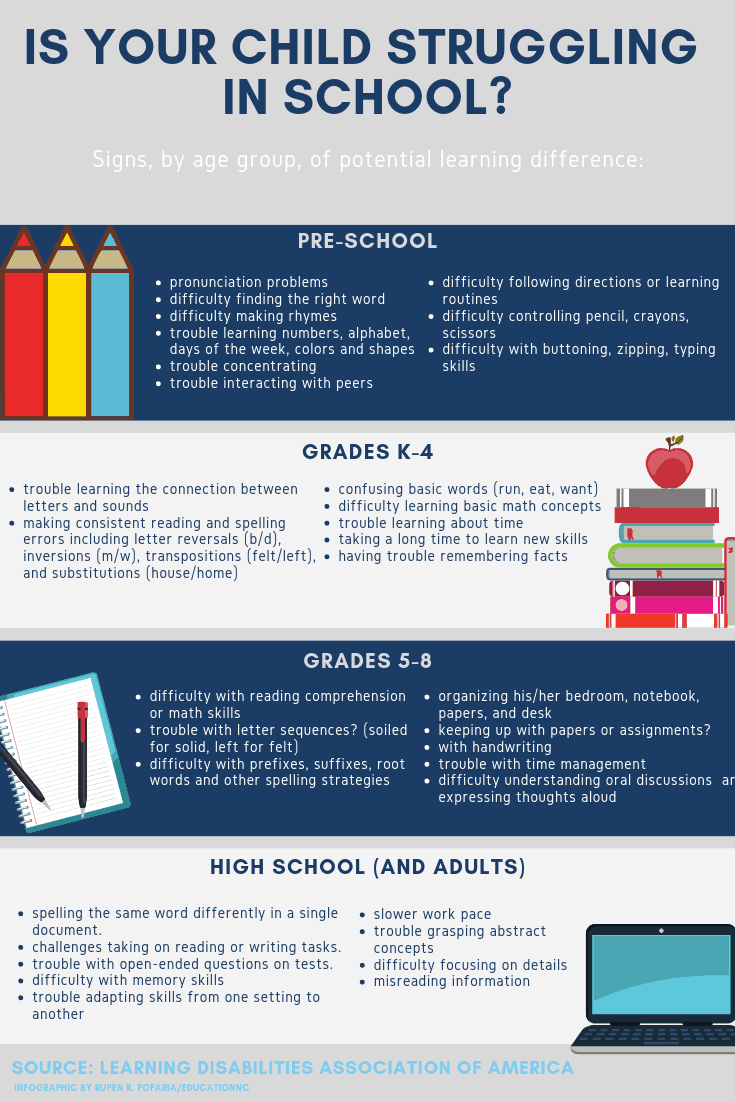

According to the Learning Disabilities Association of America, warning signs are best broken down along age ranges:

Pay attention and trust your gut

Without clear rules, it can be distressing for parents who suspect their child is struggling.

Particularly during younger ages, it can be difficult to discern when these issues point to a learning difference or when they reflect a child developing at their own pace.

“Especially in this country, we tend to want people to be developing at the same rate, and you know, everybody to hit the very middle of that bell curve,” Fogg said. “But there wouldn’t be a bell curve if there weren’t kids on the opposite ends of the spectrum. And so, just because that’s happening doesn’t mean that you need to panic or assume that there definitely is an issue. But definitely be on the lookout for anxiety and how anxiety takes many forms.”

Fogg cautions parents not to be hard on themselves. There are a lot of signs to look for and a lot of things going on in every day life.

“And you can have advanced degrees and be a very attentive parent,” she said. “That doesn’t mean that you’re necessarily going to recognize it. And I don’t think that means that you’ve done anything wrong … it just takes some time to figure it out.”

That said, if you see some of these signs, don’t ignore them assuming they will correct themselves or write them off as an overreaction. You know your child best, so experts say to trust your gut and — at the very least — start monitoring and recording red flags.

This is especially important because early detection correlates strongly with a child’s ability to thrive with a learning disability.

What to do when you think there’s a problem

Parents can go quickly from not wanting to acknowledge a learning difficulty straight to wanting a learning disability diagnosis. But there are things that can be done in between.

“It doesn’t necessarily need to go to a special education referral at that point,” Loeser said. “Oftentimes, I think the parents are going to the school and they’re saying, ‘I want to get my child evaluated,’ because the parent is frustrated and they just want their child to get help. They think that special education is the only way to get that help, and what we need to do better as a system is, at the front end, explaining to parents the system of support that we have available to support students who struggle.”

The system of support, which has been implemented over the past year, is a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS) that helps teachers try preliminary interventions prior to pursuing formal evaluations for special education services. This used to be called response-to-intervention, or RtI. The MTSS guidebook can be found here.

“The first step is go to the school and talk to them, and be clear about why they think that and what are their concerns and just start trying to pinpoint those areas of concern,” said Loeser.

Loeser recommends going directly to the teacher. If you don’t get a response or if you don’t get a response quickly enough, she recommends turning to the principal. If you still feel your concerns are not addressed, then you can reach out to the exceptional children (EC) director. Every district has an EC director, and you can find a list of them here.

“And then the school’s responsibility to do that is to really help answer those questions for the parents and share the information and data that they have and jointly determine, you know, where they need to go from here,” she said.

Where they go, and how that might look, can vary. MTSS may look like:

- regular classroom teachers giving the child specific instruction in a way that maybe they’re not giving the entire class — either during group discussion or one-on-one,

- using a different methodology or delivering the instruction differently,

- using visual instructions, written instructions instead of verbal instructions, or vice versa,

- repeating instructions for a child, or

- offering instruction in a different environment — such as a calmer or more controlled setting.

As MTSS interventions are attempted, the school should be tracking data to determine when something is not working and — more importantly — when something is. North Carolina schools are now using a tracking software called Every Child Assessment and Tracking System (ECATS), which monitors interventions and promotes collaboration among different teachers.

“We’ve got teams within the school who are regularly looking at that universal screening data and we’re looking at those students who are receiving intervention as a group that we’re monitoring,” Loeser said. “So the point is, we’re trying to take the burden away from the individual teacher to monitor these things and so we’ve got a system in place that is monitoring the progress of all students and the system identifies those kids that may need additional support.”

Loeser said that MTSS is still being rolled out for some uses, and it’s being improved.

“In the ideal world where we’re trying to get to … the school would have built into their system of support defined ways that we can provide intervention to students who have kind of these kind of needs,” she said.

If standard interventions aren’t working — evidenced by lack of progress — then it may be time to get your child tested for learning differences. The school should do this, but be proactive about monitoring your child’s progress. Take that process into your own hands, because schools sometimes won’t, says Fogg.

“I think it’s easy sometimes for a parent to get reassured by the school that your child is really not behind,” she said. “Sometimes, grades on report cards don’t accurately reflect where your child is. Sometimes, you know, they’ll say a particular child is not a good fit with that teacher. That could just literally be that they’re not a good fit with that teacher and that they don’t respond to that style — or it could be an indication that there’s a problem.

But if if your child is not making the progress they should make, I think it’s easy for them sometimes to say, well, we’ll just figure it out next year or we’ll work on some of this stuff over the summer. And sometimes that’s really hard.”

In that case, parents can take matters into their own hands, either by finding a child psychologist (which can be via pediatrician referral) to perform a psycho-educational evaluation, or by making a parent referral for special education services evaluation directly to the school. Getting an independent or private evaluation can garner more attention from the school, because those reports, Fogg says, are harder to ignore.

The next chapter in this guide, available tomorrow on EdNC.org, will dig deeper into how to get the evaluation process started, explore the differences between the assistance offered under the learning disabilities laws, and explain how to navigate the process of getting your child help under either IDEA or 504 laws.

Correction: A previous edition of this post incorrectly attributed information on the warning signs of a learning disability to the Learning Disabilities Association of North Carolina. It has been updated to attribute the information to the Learning Disabilities Association of America.

Recommended reading