Editor’s note: This article is part of a series on the intersections of community colleges and child care. Other articles in the series are available here.

The North Carolina Community College Child Care Grant helped Jaleesa Gilmore pay for 100% of her 5-year-old daughter’s child care expenses this school year.

“Just getting it, I was ecstatic,” she said of the funding.

Gilmore is a student at Central Piedmont Community College in the respiratory therapy program. She’s also one of the 737 student parents across the state who benefitted from the N.C. Community College Child Care Grant program, an annual allocation of just over $3 million in state funding designed to help student parents at community colleges pay for child care.

For students enrolled at community colleges with children, the rising cost of child care is often a barrier to enrollment and completion. North Carolina is one of a few states that has a solution to this problem — the N.C. Community College Child Care Grant gives each of the 58 community colleges grant funding to distribute to student parents to help them cover child care costs.

Last year, EdNC analyzed how the state’s community colleges have historically spent this annual allocation. We found that, in the previous three years, only three community colleges had consistently spent 100% of their allocated funds, and about half of the system’s colleges spent less than 90% of their funds. At the end of the 2023-24 fiscal year, there was nearly $700,000 in unused grant funding.

In the 2024-25 fiscal year, the amount of unspent funds decreased. According to the grant’s 2024-25 annual report, about $467,000 was unused at the end of the fiscal year. Across all 58 community colleges, compared to the previous fiscal year, the grant awarded just over $211,000 more to student parents navigating their academic and family responsibilities.

![]() Sign up for Awake58, our newsletter on all things community college.

Sign up for Awake58, our newsletter on all things community college.

EdNC spoke with representatives from the North Carolina Community College System and several community colleges in 2024 to understand the barriers to getting this money to students and learn from the colleges that consistently spent all of their allotted child care grant funding. We found that while there are some barriers over which colleges have no control — for example, when the legislature passes the state budget — the grant provides colleges with a lot of flexibility to determine their policies.

Colleges that are successfully spending all of their funding each year have reevaluated their requirements for student parents and taken advantage of the grant’s flexibility to help as many students as possible. While challenges persist, the increase in expended funds during the last fiscal year suggests that colleges have, and continue to, implement the grant program in a way that prioritizes connecting student parents with financial support by taking advantage of the grant’s flexibility.

Overview of the N.C. Community College Child Care Grant

The North Carolina Community College Child Care Grant is state aid directed to help student parents at North Carolina community colleges pay for child care. The North Carolina General Assembly (NCGA) has allocated this funding to the state’s 58 community colleges since 1993, and it is administered through the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS). Financial aid teams at each college are tasked with connecting student parents with the funding.

In the last four fiscal years (FY), funding for this grant totaled $3,038,215 per year. In FY 2024-25, each of the 58 community colleges received a base allotment of $20,000 and an additional $10.16 per curriculum budget full-time equivalent student, or the number full-time equivalent students for which a college is budgeted to serve.

Eligibility requirements

The grant program supports a variety of child care configurations, recognizing child care as a person, business, or organization that provides child care service to its clients. This means that student parents can use grant money to help pay for services from licensed or unlicensed providers, grandparents, nannies, afterschool programs, and summer programs. Parents themselves may not be paid for child care.

The NCCCS directs colleges to “jointly determine the need of student parents for child care in coordination with local social services agencies that provide child care funding for qualified students.”

In addition, the same NCCCS policy document reads, “funds must be disbursed directly to the provider or the student parent only upon receipt of an invoice from a child care provider accompanied by a student’s class attendance report.” The NCCCS stipulates that funds must be dispersed only after child care services are provided, and that they must pass a “reasonable test for cost.” For example, a student parent whose grandparent is providing child care services can’t submit an invoice that exceeds the average cost of child care in their area.

The N.C. Community College Child Care Grant Program is just one way the state’s community colleges support student parents. Some community colleges also have drop-in child care and licensed child care facilities on their campuses, host support groups for student parents, and support student parents with additional funding through scholarships.

Read more about child care and community colleges

A look at the 2024-25 data

Grant utilization increased in FY 2024-25, as the grant’s annual report shows. As a whole, the state’s 58 community colleges left less grant funding on the table than in previous years.

NCCCS reported that colleges awarded $2.56 million in grant funds in FY 2024-25, spending 84.4% of total allocated funds. This represents a 9% increase in awarded funds compared to the previous fiscal year. Unexpended funds totaled $467,084.91 in 2024-25, a $225,187.31 decrease from last year’s $692,272.22.

EdNC noted that in FY 2023-24 and FY 2024-25, the total amount awarded to students plus unexpended funds do not equal the total $3,038,215 allocation from the NCGA, by a margin of less than $5,000. Brenda Burgess, state director of student aid at NCCCS, confirmed that the data in the grant’s annual reports are self-reported by colleges, explaining discrepancies between the fund amounts allocated to colleges and the amount of funds each college reports to have awarded and not expended.

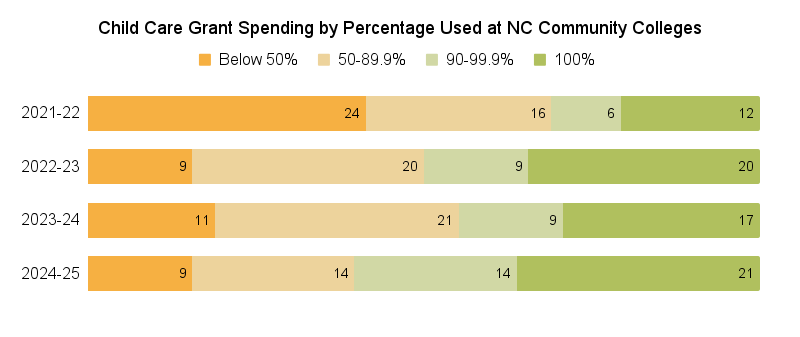

In FY 2021-22, only 12 of the state’s 58 community colleges spent 100% of their allocated funds. In FY 2024-25, 21 community colleges spent all of their grant funds, the largest number of colleges to do so in the last four years.

Conversely, the proportion of colleges spending less than 90% of their allocated funds has decreased to the lowest point in the last four years. Last year, over half of the state’s community colleges were in this category, compared to roughly one-third in FY 2024-25.

In the table below, each percentage of funds expended is taken from the NCGA’s $3,038,215 total annual allocation.

| Fiscal year | Total % of funds expended |

|---|---|

| 2021-22 | 61.2% |

| 2022-23 | 82.3% |

| 2023-24 | 77.4% |

| 2024-25 | 84.4% |

Part of the reason for the recent increase in expended funds is an approved reallocation process that took place near the end of FY 2024-25 and released additional funds to five community colleges. According to Burgess, colleges that spent all of their grant funds reached out to the NCCCS to ask if they could have additional funding. From there, Burgess said she was able to identify colleges that had already let the system office know they would not be spending all of their allocated grant funds, and those funds were then reallocated to the colleges that requested more.

According to the grant’s annual report, the five community colleges that received additional funds through the reallocation process were Bladen, Edgecombe, McDowell Tech, Piedmont, and Wilkes. All five spent 100% of their allocated funds in FY 2024-25.

The average award amount student parents received also increased by almost $500, moving from an average award of $3,263.18 in FY 2023-24 to $3,726.34 in FY 2024-25.

A total of 737 students received grant funds in FY 2024-25. Five fewer student parents received awards compared to the previous fiscal year.

| Fiscal year | Total # of students served | Average grant award |

|---|---|---|

| 2021-22 | 676 | $3,022.87 |

| 2022-23 | 744 | $3,593.82 |

| 2023-24 | 742 | $3,263.18 |

| 2024-25 | 737 | $3,726.34 |

The 2024-25 grant report also notes that 377 students were not awarded grant funds. Burgess clarified that this number reflects students who submitted applications at their college but were ultimately deemed ineligible due to various factors as determined by their college. This could include failing to satisfy academic progress or submit required documents.

Digging deeper into the data, the community colleges with the highest and lowest percentages of funds expended don’t appear to be systematically different from one another. The community colleges expending both the most and least grant funding include those serving rural, suburban, and urban counties, as well as the most and least economically distressed counties. Child care deserts also exist indiscriminately among the counties these community colleges serve, with few exceptions.

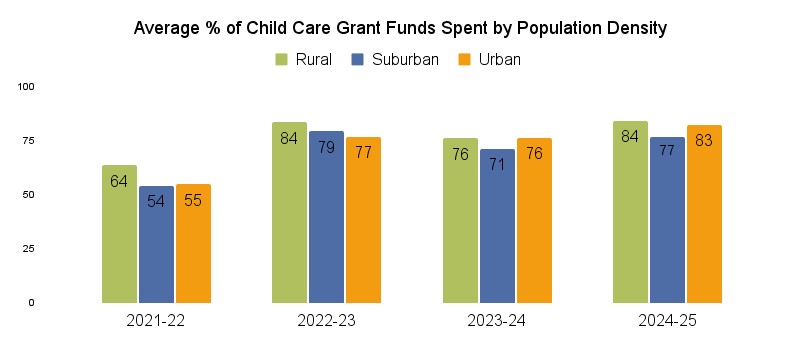

You can see the upward trend in grant use in the figure below, which organizes expenditures by the community colleges’ service area population densities. Colleges’ service areas were classified using the NC Rural Center’s definition of rural, urban, and suburban population densities.

Over the last four years, rural-serving colleges allocated the same or a slightly higher share of child care grant funding than their suburban and urban counterparts, and urban-serving colleges saw the greatest increase in the share of funds spent. Between FY 2021-22 and FY 2024-25, the average percent of funds spent for urban-serving community colleges jumped from 55% to 83% — a 28 percentage point increase.

However, it is worth noting that the state has far fewer urban-serving community colleges (four) than rural-serving community colleges (41). This means that, overall, rural colleges receive and spend a greater portion of the entire $3 million allocation from the NCGA. It also means that for urban-serving community colleges — Durham Tech, Wake Tech, Central Piedmont, and Guilford Tech — any change in the percent of funds spent has a greater impact on overall urban spending than a change at one of the 41 rural community colleges.

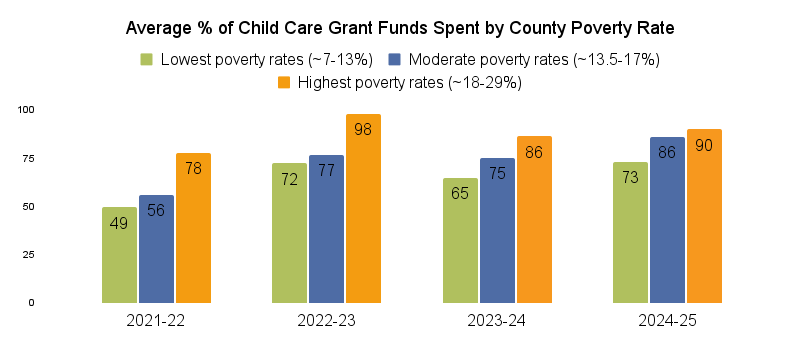

Looking at community colleges’ child care grant spending by their service counties’ poverty rate reveals that, on average, community colleges with service areas that have the highest percentage of people living in poverty generally spent a higher share of their allocated grant funds.

Note that each poverty band below includes roughly a third of the state’s community colleges.

Over the last four years, a total of nine community colleges consistently allocated at least 90% of their child care grant funding to student parents.

Three community colleges consistently allocated 100% of child care grant funding:

- Brunswick Community College

- Caldwell Community College and Technical Institute

- Carteret Community College

Three community colleges consistently allocated more than 97% of child care grant funding:

Three community colleges consistently allocated more than 90% of child care grant funding:

Hurricane Helene’s effect on grant use

Child care grant use varied at the 14 community colleges impacted by Hurricane Helene in September 2024. In FY 2024-25, the percent of grant funds used decreased at six colleges, remained at 100% at four colleges, and increased at four colleges, compared to the previous fiscal year.

Caldwell Community College and Technical Institute, serving Watauga and Caldwell counties, is one of the three colleges statewide that spent 100% of grant funds each of the last four years. McDowell Tech, Surry, and Wilkes are the other western community colleges that spent all of their grant funds in FY 2023-24 and continued that trend in FY 2024-25.

Four colleges impacted by Helene saw an increase in grant funds spent between FY 2023-24 and FY 2024-25. The largest percentage point increases were at Gaston College and Haywood Community College, where grant utilization increased from roughly 35% in FY 2023-24 to 99.9% and 88% in FY 2024-25, respectively.

At the remaining six colleges impacted by Helene, decreases in grant fund utilization ranged between roughly three and 60 percentage points. Western Piedmont Community College in Burke County experienced the largest decrease. Between FY 2021-22 and 2023-24, the college’s average percentage of grant funds spent was 98%. In FY 2024-25, the college’s percent of grant funds spent decreased to about 40%.

While it’s unclear if the hurricane had a direct role in child care grant fund use at these community colleges, previous EdNC reporting highlights the role Helene played in surfacing the need for child care in impacted communities and the role community colleges play in filling that need. The grant, then, plays a crucial role for students in western counties where child care is both scarce and, often, unaffordable.

Barriers to full utilization of child care grant funds

The 2024-25 grant report includes results from a survey the NCCCS gave to colleges to gather feedback on the grant program, and its findings closely align with the challenges discussed in EdNC’s previous analysis of the grant. Taken together, both the NCCCS’s survey and EdNC’s reporting identified that the timing of the state budget coupled with challenges in the grant’s reimbursement model are barriers to colleges using the funds.

Delays in passing the state budget

An ongoing challenge in grant use is the timing of when community colleges actually receive the grant funds. Colleges operate on an academic calendar and the grant program is based on a fiscal year. Because the grant disbursement depends on an annual legislative allocation, if the NCGA does not pass a state budget before classes begin in August, then community colleges do not receive the grant funds until after the semester begins.

And, in turn, student parents don’t know if, or when, they can count on the financial support to help them pay for child care.

“Every day that that state budget doesn’t come in, just at our school alone, dozens of students are affected,” Maggie Brown, Carteret Community College’s vice president of instruction and student support, told EdNC last year.

The NCCCS report adds that the timing of when funds are dispersed is “often too late to allow students to make informed childcare plans before the semester begins,” and that, as a result, “some students postpone enrollment or seek alternative solutions due to uncertainty about funding.”

Burgess confirmed that funds for this academic school year, the 2025-26 fiscal year, were approved through the mini-budget the legislature passed in late July 2025, and that funds arrived at colleges in September.

The reimbursement model and its administrative requirements

Another challenge is the grant’s reimbursement model. Last year, EdNC learned that a point of confusion that appeared to hinder grant expenditure was whether or not colleges are allowed to reimburse student parents directly for child care expenses. According to NCCCS policy, “funds must be disbursed directly to the provider or the student parent only upon receipt of an invoice from a child care provider accompanied by a student’s class attendance report,” followed by, “Neither the student parent, nor the other parent of the child may be reimbursed for services.”

While the first sentence says colleges are allowed to reimburse student parents for child care expenses they have paid for out-of-pocket, some colleges interpreted the second sentence to mean that students can’t be reimbursed at all and the money has to be paid directly to child care providers after they provide services.

When EdNC asked Burgess to clarify this, she said colleges are able to reimburse student parents for child care services for which they’ve paid “so long as it’s part of their adopted procedure.” Clarifying this rule meant that colleges have more flexibility and autonomy in how they can disperse grant funds to student parents, enabling them to spend down more of their allocated funds.

However, the 2024-25 grant report sheds light on some of the challenges around this reimbursement model. Most child care providers require payment before providing services. Per the current policy, grant funds cannot be dispersed to the provider nor the parent until the service is provided. According to the report, this creates challenges for students who can’t pay for child care upfront and for child care providers who rely on timely payments. “Delays between service and reimbursement (often 4–6 weeks) are challenging for both providers and students,” reads the report.

Central Piedmont student Gilmore said she received her child care grant reimbursement for the fall 2025 semester in early December. The funds covered 100% of her daughter’s child care costs that she’s paid since August, or about four months of child care payments.

Now in the second year of her respiratory therapy program, Gilmore works as a respiratory care assistant and says the guaranteed schedule makes it easier for her to make a financial plan every month compared to her job last year.

“I feel like if you’re in a situation where your income isn’t consistent, then it could be very challenging to get the money months after the fact,” said Gilmore.

The grant report’s suggested improvement to the reimbursement model is to “explore options for direct or upfront payments to childcare providers, particularly for summer programs or semester start periods.” In other words, allow the funds to also be used to make upfront payments to child care programs at the time a student parent would have to pay the bill, before services are provided.

The paperwork a student submits to receive reimbursement for child care each month can also create administrative burdens for college’s financial aid offices, which may further delay dispersing funds. According to the report, Southeastern, Randolph, and Alamance community colleges shared that “collecting monthly vouchers and managing reimbursement paperwork is time-consuming for financial aid offices,” and that “monthly voucher requirements make the program administratively intensive and limit flexibility” at Randolph Community College.

The report mentions that many students stop submitting monthly vouchers partway through the semester, which leads to gaps in fund use.

Similarly to this year, Gilmore said that, last year, she received her grant disbursement several months after submitting child care receipts, including in the summer for her payments made in the spring semester. “If I knew when it was coming, then I can allocate better as far as my finances, instead of just kind of expecting it every month,” she said of the grant funds.

I feel like if you’re in a situation where your income isn’t consistent, then it could be very challenging to get the money months after the fact.

— Jaleesa Gilmore, Central Piedmont Community College respiratory therapy student

Gilmore also suggested that it would be helpful if, at Central Piedmont, her experience receiving the grant operated similarly to other financial aid programs. Real-time processing updates on the invoice documents she submits or an expected date to receive funds, Gilmore said, would be helpful.

The grant report’s proposed solution to these administrative and operational burdens is for the NCCCS to “treat childcare funds more like traditional grants with upfront disbursements or term-based payments, reducing administrative burden and increasing flexibility for students and providers.”

In addition to suggesting earlier funding notifications, the grant report also suggests for the NCCCS to “allow grant-style disbursements (e.g., lump-sum payments at the start of the term) to improve accessibility and ease administrative work.”

In short, based on feedback from colleges and proposed solutions in the grant report, the option to shift from reimbursement to upfront payment for child care could increase the amount of overall grant funds spent, make the grant work better for student parents, and ease administrative burdens on colleges’ financial aid offices.

How can colleges get more child care grant funding to student parents?

Changes to the NCGA’s legislative timeline and shifts in the grant’s funding structure may take more time to come to fruition than the efforts happening at individual colleges that are actively connecting more student parents with funds.

From the system office’s perspective, Burgess continues to encourage colleges to take full advantage of the grant by reevaluating their current operating procedures and eligibility requirements.

One way colleges can do this is by letting their student parents know throughout the school year that grant funding is available. Carteret Community College, one of the three colleges that spent 100% of their funds in the last four years, told EdNC in 2024 that when they have grant funds remaining, their financial aid team will reach out to eligible students and let them know they can bring in receipts for child care services to be reimbursed if they haven’t already.

This year, Burgess praised Central Piedmont for similar efforts.

“They said that they were sending out emails, they were making phone calls, text messages, and just encouraging students to come in with and bring any receipts for out-of-pocket expenses that they had incurred. So they were able to assist a lot of students there,” she said of Central Piedmont.

One of those messages ended up on one of Gilmore’s class announcement pages, telling students to connect with the financial aid office if they have child care expenses. “There was somebody in my class that didn’t know about [the grant], and she sent in her information, and she was able to get the reimbursement,” Gilmore said.

Central Piedmont awarded all but $760.19 of the college’s nearly $185,000 grant allotment in FY 2024-25 and spent 100% of grant funds in the two fiscal years before that.

Another way colleges have made the grant more accessible is by removing eligibility requirements for students. When it comes to who is actually eligible for the grant, “it’s pretty much at the discretion of the colleges,” Burgess told EdNC last year. In other words, it’s up to colleges to decide on procedures for distributing the grant to their student parents.

For example, Burgess praised Rockingham Community College for “taking a thorough look” at the rules they had in place surrounding the grant and making significant changes to their eligibility, including expanding the grant to students enrolled less than half time. In FY 2023-24, Rockingham spent about 53% of their funds — in FY 2024-25, they spent 100%.

Expanding eligibility to online students, continuing education students, and military students are all options that can remove barriers for student parents seeking child care assistance.

Sarah West, chair of the N.C. State Board of Community Colleges Programs and Student Success Committee, provided context on the grant’s report at the Board’s November meeting. She noted that Dr. Brian Merritt, senior vice president and chief academic officer at the NCCCS, and other system office staff met with chief financial officers at community colleges to understand challenges to using the funds.

“I think some of the things (Merritt) found was that colleges didn’t really understand the full creative opportunity to deploy the funds across a different range of programs, so a lot of work is going on to try to really fulfill these funds,” said West, echoing Burgess’ remarks.

Colleges also have autonomy to determine the kinds of documents required for student parents during the grant application process.

The NCCCS directs colleges to “jointly determine the need of student parents for child care in coordination with local social services agencies that provide child care funding for qualified students.” Some community colleges take this to mean they have to require students to obtain documentation of being waitlisted, denied, or actively receiving funds from their local department of social services (DSS). This can result in colleges adding these requirements, which can be cumbersome for students, to their administration of the grant.

When EdNC asked Burgess about this last year, she clarified that colleges should make sure that they aren’t giving student parents more grant money than they need if they’re already receiving DSS funding, but that colleges should not make it a barrier for students if the process for documentation is difficult and time consuming.

Additionally, in the 2024-25 grant report, a suggested improvement to eligibility criteria is to “clarify the necessity of DSS referral in program guidelines and explore flexibility for colleges to independently determine eligibility when local DSS funding is unavailable or delayed.”

Looking forward

As colleges continue to receive N.C. Community College Child Care Grant funding each year, it is clear from the last two years of EdNC’s reporting that open communication channels between students, their financial aid offices, and the system office have been pivotal in connecting more student parents with funding.

“Hopefully, the monies that are being reverted each year will continue to go down, and we hope to, at some point, see zero that’s being returned, because we want to do everything that we can from the system to ensure that our colleges are using every dollar,” said Burgess.

West also noted at the November State Board of Community Colleges meeting that the grant program is part of a broader discussion around the role of community colleges in addressing the state’s child care needs. She suggested partnership with the N.C. Task Force on Child Care and Early Education — co-chaired by Lt. Gov. Rachel Hunt, who also serves on the State Board of Community Colleges — to bring greater attention to the grant. Part of the task force’s two-year charge is to produce a report on how the state should expand access to high-quality, affordable child care.

“It’s a long-term problem that we’re going to seek solutions for,” Hunt said in response to West’s remarks.

In the meantime, for student parents like Gilmore, the grant funding continues to support her daughter’s future as she works toward graduating from Central Piedmont in May.

Editor’s note: This article was updated to include Craven Community College and Pitt Community College on the list of colleges that allocated more than 90% of child care grant funding over the last four years.

Recommended reading