Share this story

- This two part series explores the context of higher education, the development of the current governance model in North Carolina, and a comparison of that model to those used in other states.

- Paying attention to the distinctive nature of community colleges, researchers offer comparisons of cross-state postsecondary governance structures, showing where the North Carolina Community College System stands.

|

|

Highlights

- No two states have an identical governance structure for their systems of higher education, but looking to other states could help North Carolina understand its own challenges and opportunities.

- According to the Education Commission of the States, North Carolina has “multiple statewide governing or coordinating boards,” which point to the UNC System and State Board of Community Colleges.

- Some advantages of this model are that the community college system can set its own priorities.

- However, this model can also lead to inefficiencies and struggles to uniformly implement policy across the state.

Part II

As illustrated by the history of the North Carolina Community College System (NCCCS), postsecondary governance models emerge from “a complex web of relationships and arrangements that have evolved over time.” 1 This means that “no two states or the District of Columbia have the same underlying governance structure.” 2

This reality limits the usefulness of interstate comparisons, although a broad appreciation of differences can help leaders “better grasp their own systems … and more effectively respond to changes in the state’s demographic, education goals, and economic conditions.” 3 To aid that process, numerous researchers have proposed high-level categorization systems for higher education in general and for community colleges in particular.

General state governance models: The ECS model

The first systematic classification of state governance systems of postsecondary education arguably appeared in 1959, with new and revised typologies appearing periodically ever since. 4 Importantly, most all studies argue that no one governance model is inherently “best” or superior. The pivotal question is instead whether a model advances a state’s education goals. 5

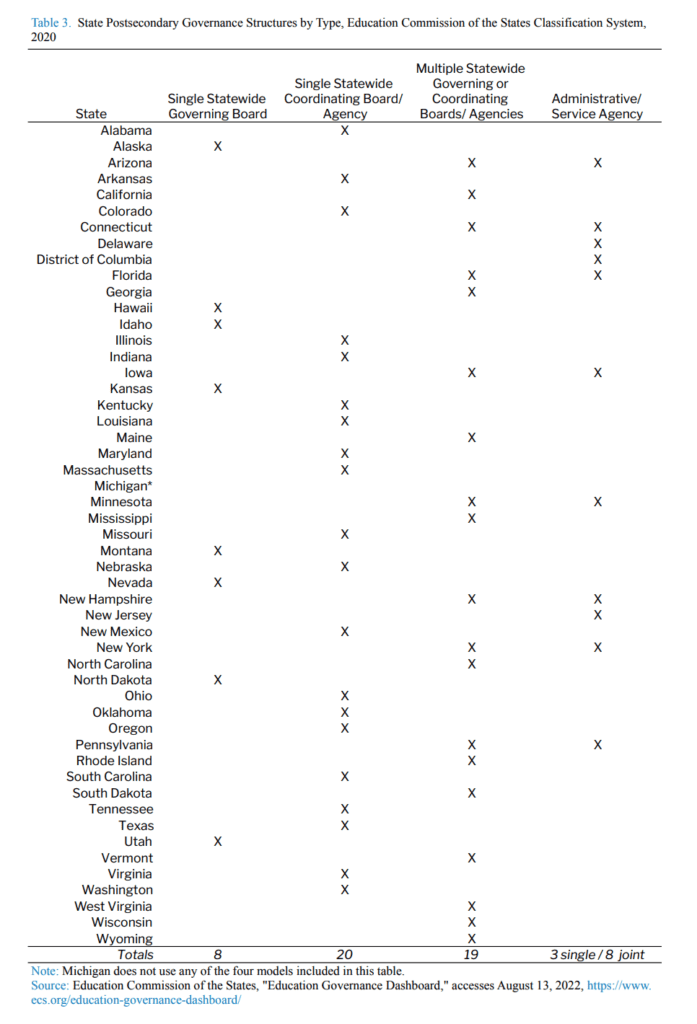

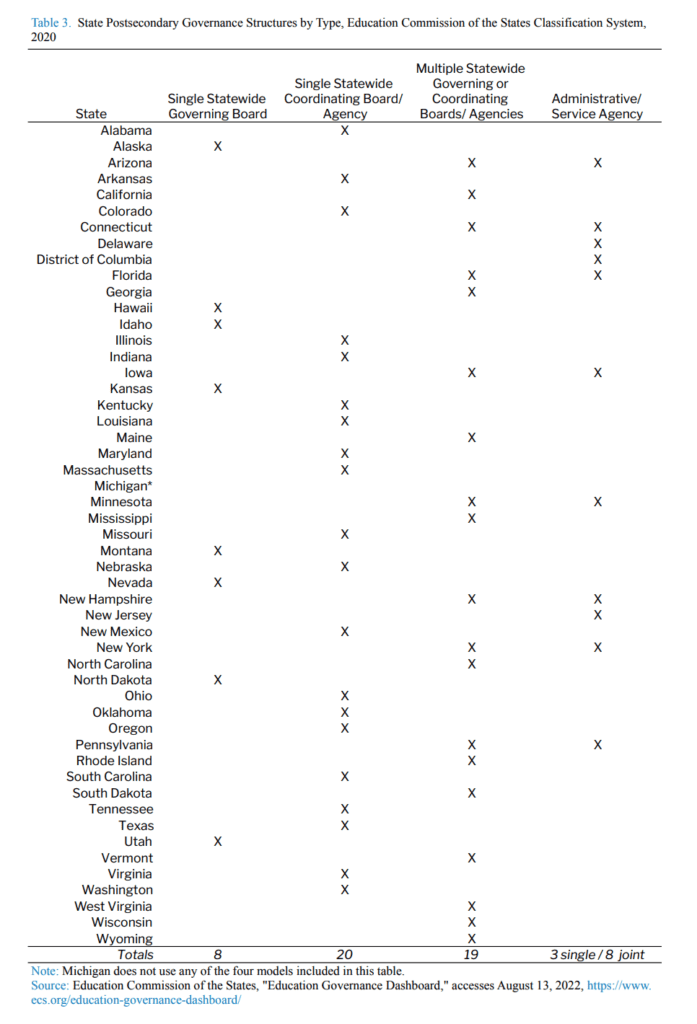

One popular typology is that of the Education Commission of the States (ECS), an interstate compact formed in 1965 to support governors, legislators, and other state education leaders. 6 As an outgrowth of several task forces convened during the 1970s, ECS proposed a framework for classifying overall state governance models based on organizational structures, the legal powers granted to entities, and how overall higher education planning is coordinated. A key dimension is whether the entity possesses governing powers or coordinating powers. A second dimension is whether the entity enjoys statewide authority over the entire postsecondary education system or limited authority over a subset. Using this framework, the ECS groups state systems into four broad categories. 7 See how state systems are grouped by ECS below, as well as an explanation for each of the four governance models.

Single Statewide Governing Board: In this model, there exists a single organization “whose primary functions, responsibilities, and duties relate to the actual control or governance of their constituent institutions.” 8 Such boards generally enjoy broad powers, and some may exercise statewide planning functions as well. As of 2020, the model is used in 8 states.

Single Statewide Coordinating Board or Agency: In this model, a central statewide body exists but exercises no governance authority over any institution or system. Instead, it is “responsible for coordinating the efforts of higher education institutions and other leaders in the state—the governor, the legislature, and the institutional governing boards and/or the multi-campus boards that govern the state’s institutions.” 9 Some boards possess regulatory powers, but others play solely advisory roles. As of 2020, the model is used in 20 states.

Multiple Statewide Governing or Coordinating Boards or Agencies: In this model, there exist multiple bodies responsible for governance and/ or coordination. In a state with multiple governing boards, one might oversee the public universities, another the community colleges. In other states, one board might govern one system (e.g., universities), while a different body coordinates another (e.g., community colleges). As of 2020, the model is used in 19 states.

Administrative/ Service Agency: In this model, governance authority rests with each college and university, but a central statewide body exists to support the individual institutions with matters like financial aid. Some states use an administrative/service agency jointly with another model. As of 2020, the model is used in alone in 3 states and jointly with another model in 8 states.

Under the ECS typology, North Carolina has “multiple statewide governing or coordinating boards.” The State Board of Community Colleges (SBCC) governs the community college system, and the UNC Board of Governors governs the universities. While the two boards collaborate, neither has power over the other, nor is there an overarching body to coordinate the entirety of postsecondary planning and policymaking.

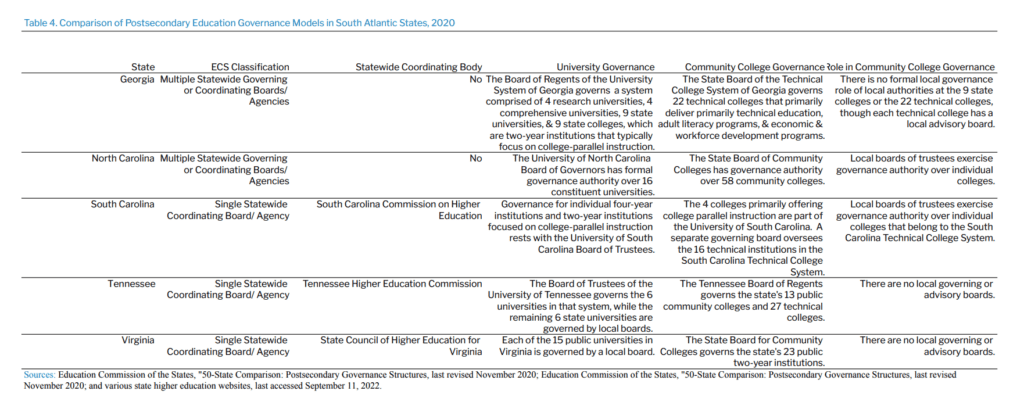

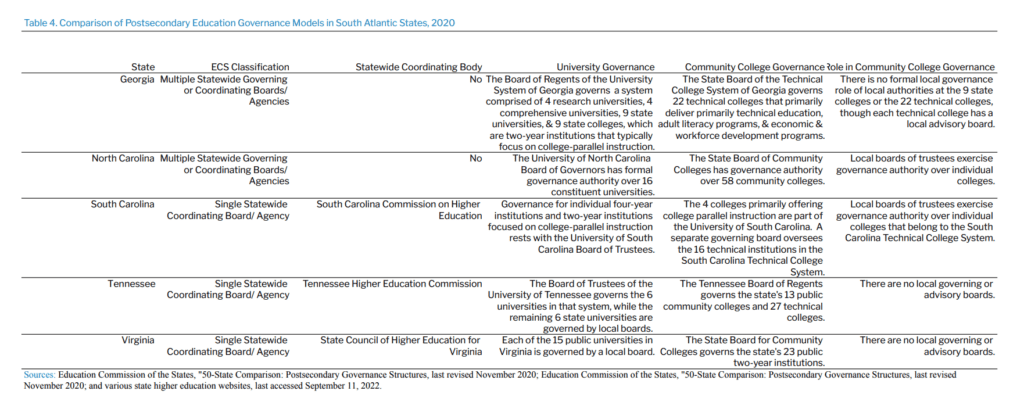

North Carolina’s neighbors in the South Atlantic employ a diversity of governance models. 10 Georgia is similar in that it has two different governing boards, but one is responsible for public four-year institutions and for certain two-year institutions, while the other is responsible for the state’s two-year technical institutes. Virginia and Tennessee entrust governance of their public four-year and two-year institutions to different entities, but both states have formal statewide coordinating bodies. South Carolina also has a statewide coordinating board, but most institutions are governed locally ,apart from a set of 16 technical institutes. 11

As noted earlier, a common viewpoint is that no governance model is inherently superior. Take North Carolina, which has two governing boards and no larger coordinating body. A benefit of this approach is that each board can focus on its own needs, ideally leading to more appropriate decision-making and the cultivation of knowledgeable champions for each system. A separation of power further may prevent one system’s needs from predominating.

At the same time, as the size of a system increases, it may prove harder for the board to understand current conditions, set appropriate systemwide policies, and ensure accountability in the same ways that can be done in a smaller system. 12 There are also risks of a board becoming more focused on institutional concerns than public ones. And without a coordinating entity, the two systems may unintentionally find themselves duplicating efforts or working crosswise.

Community college governance models: Beyond the ECS framework

Despite its ubiquity, the ECS classification system is better suited to appreciating differences in university rather than community college governance. Community colleges exist “betwixt and between” public K-12 schools and universities, and they “have been seen at various times as an extension of high school; as the first 2 years of a college system, and as a unique educational enterprise separate from both secondary and higher education.” 13

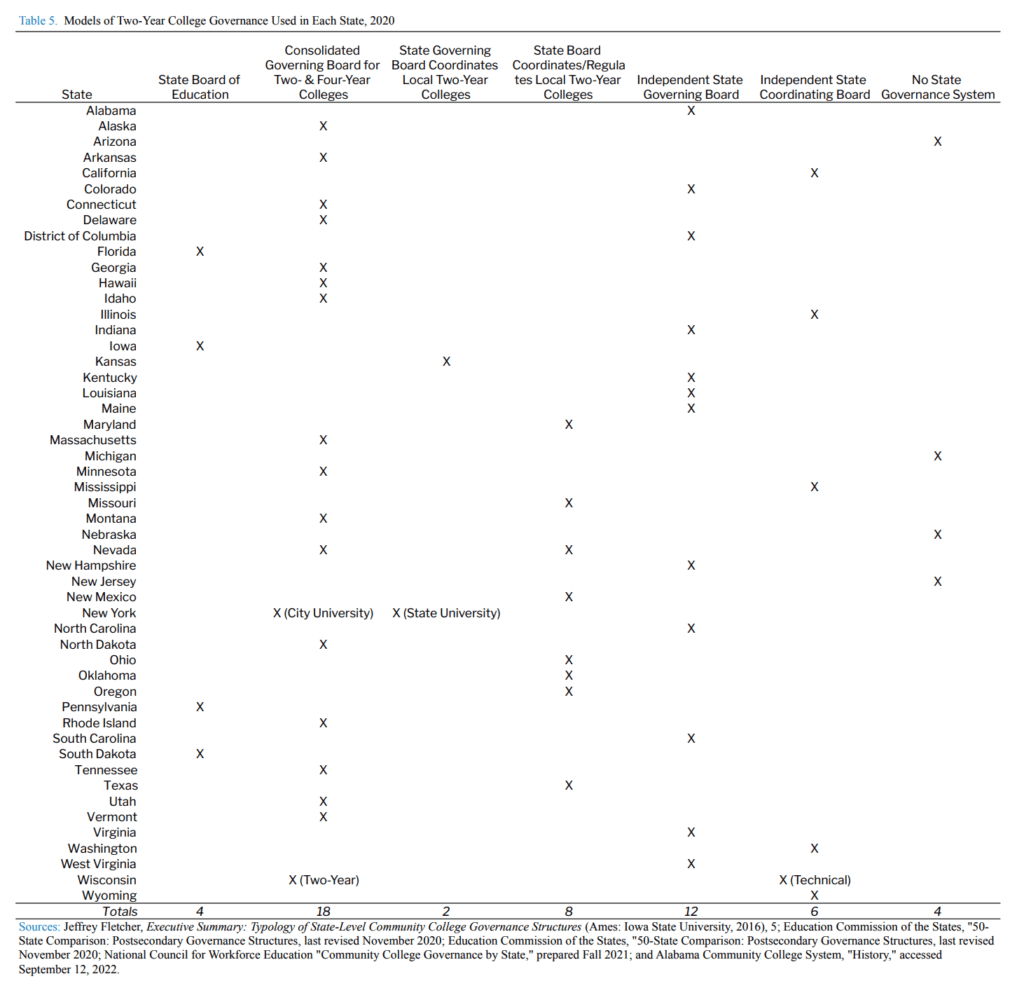

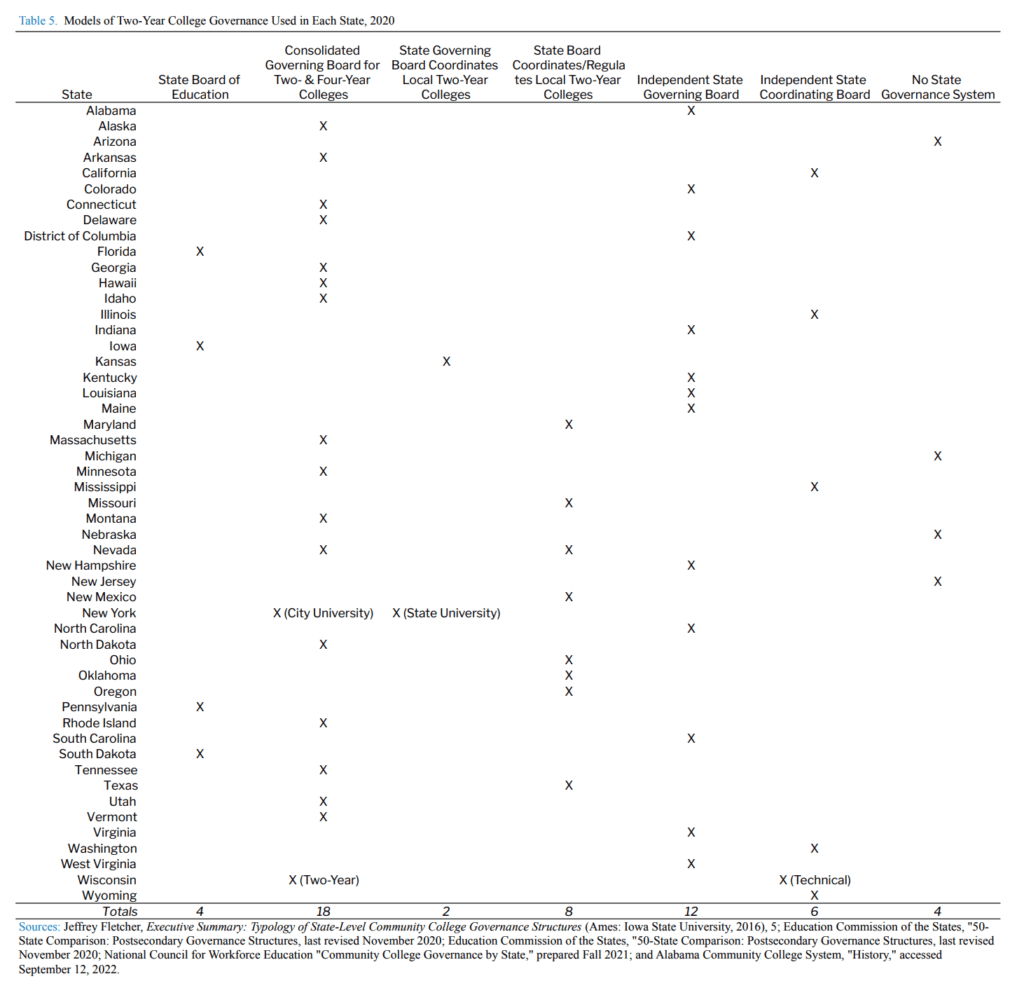

Even today, some states, like Florida, govern their community colleges through their K-12 systems, while others, like North Carolina, govern them as a distinct postsecondary system. And some states govern two-year colleges focused on academic instruction differently from technical institutes.

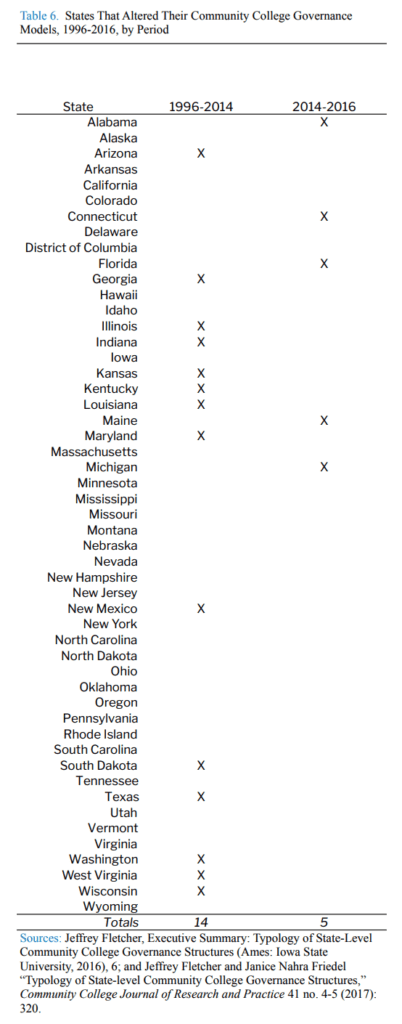

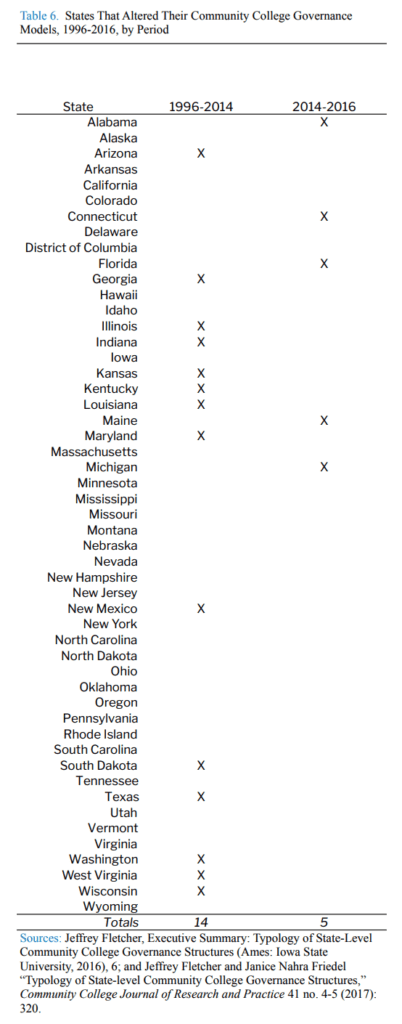

Further complication stems from periodic changes to state governance models. By one count, at least 14 states altered their governance models between 1996 and 2014, with another five states believed to have enacted changes between 2014 to 2016. 14 For instance, Alabama established a statewide Board of Trustees to govern its community colleges in 2015, thereby ending some 50 years of direct control by the State Board of Education. 15

Recent decades have seen more nuanced research into community college governance that better considers the more complex missions of community colleges as compared to the traditional scholarship, teaching, and service functions performed by public universities, as well as the distinct needs of the students enrolled in two-year colleges. An example of a more detailed typology appears below, building on the ECS framework to create seven models of governance, instead of four.

Scholars Richard Richardson and Gerardo de los Santos proposed a typology arguably better suited to community colleges. First, they looked at a state’s entire higher education system to see whether the state has “a coordinating board/agency with at least some statutory authority for serving as the interface between higher-education institutions and state government for the four central work processes: budgeting, program planning and approval, informational management and dissemination, and articulation and collaboration.” 16 If the answer is “yes,” then the state is said to have a “federal” system in which responsibilities for governing individual institutions and representing the public interest are separated. If the answer is “no,” the next question is whether the state “has more than a single governing board for all of its degree-granting, postsecondary institutions, including community colleges and technical institutes.” 17 If one board exists, the state has a “unified” system; if multiple boards exist, the state has a “segmented” system. The same two questions then are asked in relation to a state’s two-year colleges. This results in nine possible categories, though only seven actually are in use.

Richardson and de los Santos classified North Carolina as having a segmented/federal structure. 18 At the statewide level, two governing boards exist — one for the NCCCS and one for the UNC System — with neither board, nor any other entity, responsible for the entirety of postsecondary education. Therefore, North Carolina’s governance model is segmented.

When it comes to community colleges, North Carolina employs a federal structure in which the SBCC acts as the interface between colleges, their local boards of trustees, and state government. Every college is subject to the SBCC, resulting in unified governance of the state’s two-year colleges.

Unlike most studies that claim no governance model is inherently superior, Richardson and de los Santos argued that the differences matter for community colleges. States with a single body responsible for all of higher education might seem to have advantages in coordination, yet “boards with combined responsibilities for two- and four-year institutions often fail to make optimum use of the two-year sector, thus leading to problems in both coherence and efficiency.” 19 The interests of the four-year institutions frequently dominate in such arrangements, thus forcing the Board to spend “more time refereeing disputes over students, programs, and financial resource than worrying about how to best serve the public interest.” 20

The authors further argued that federal design structures are advantageous for community college systems. 21 First, such structures are more dynamic and can be tweaked as needed, rather than requiring major restructurings. Second, the division of responsibility between institutional concerns and public interests minimizes conflicts. Third, by being free to focus on institutional and systemwide concerns, the governing boards can advocate more forcefully on behalf of their systems and schools.

At the same time, states with federal systems that lack an overarching coordinating body — like North Carolina — may struggle to implement policy across the entirety of postsecondary education, limit duplication of effort, and act uniformly.

Another complication when studying community colleges is that governance categories and actual practices differ. In a 2016 paper, academics Jeffrey Fletcher and Janice Nahra Friedel classified each state’s community college governance model based on a five-part typology after reviewing historical documents. 22 They then surveyed administrators and found gaps in how administrators understood their governance systems versus the “official” models. While some discrepancies were due to recent changes, others reflected real differences in perceptions between official procedures and how decisions really are reached and implemented.