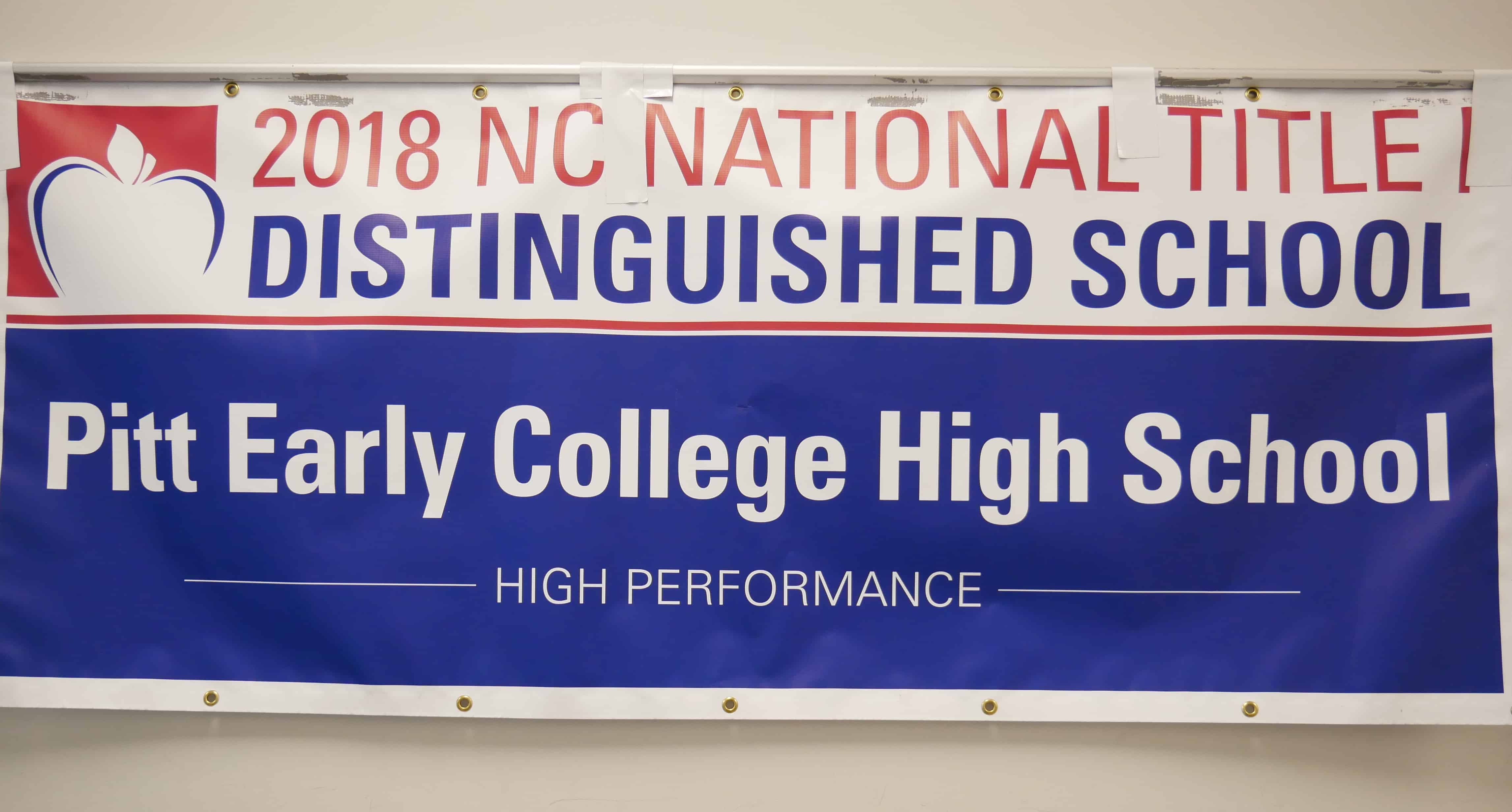

In most schools across the state, poverty is highly correlated with academic performance. But Pitt County Early College High School, where more than 80% of students are economically disadvantaged, is an exception to that trend.

For each of the five years of its existence, the school has received A’s on the state performance grading scale and exceeded growth standards. For three years in a row, the school has been nominated as one of two schools across the state to become National Title 1 Distinguished Schools.

Principal Wynn Whittington, who has been at the school since its inception, said every part of the school was intentionally created to breed success for students — from the early college model to each staff member he hand-picked to the individualized academic and personal support students receive.

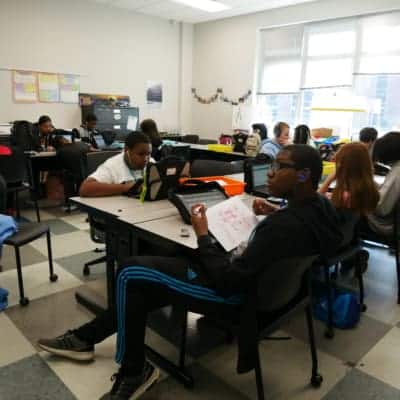

“When you can take economically disadvantaged students and the students who otherwise would probably never go to college and put them in a situation where they can thrive because they have the layers of support, they have the love of a staff, small class sizes, more personalized education, they’ll run through walls for you and for themselves,” he said. “That’s what I love about this model.”

Like other Cooperative Innovative High School (CIHS) principals across the state, Whittington said he hears people say they are only successful because they hand-pick their students. With the majority of early colleges receiving school performance scores of As and Bs, the staff must choose students who are already academically successful, or so people think.

That’s not the case, Whittington said. Almost 90% of the school’s students are first-generation college-goers. That is an intentional factor in the recruitment and interview process each year, when around 200 middle schoolers apply and 75 end up attending.

Cooperative Innovative High Schools: What are they and why does North Carolina have so many?

More than five years ago, Whittington was working at the state education department after working to turn around a traditional high school. In two years, student proficiency jumped from 43% to 69%, and Whittington was burned out. “I didn’t really want to be a principal again,” he said.

But when he heard from a colleague that an early college was opening in Pitt County, he immediately jumped on the opportunity. Having briefly spent time as the principal of Lenoir Early College, he was familiar with the model and was thrilled at the idea of starting a school from scratch. His first interview question to every teacher and staff member since has been: “Do you love children?”

“This is not like being a principal anywhere else,” he said. “You actually get to be what I consider a true principal. Your school is small enough. You know every kid’s name. And you’re able to build relationships with children and get to know them, their families, and it is truly a family atmosphere that we’ve been fortunate enough to create here.”

Whittington says basic needs of students and families always come first. Almost daily, he hears from a student who missed the bus who he goes and picks up. An account fully funded by donations from staff members and others is often used to support students’ external needs.

“A kid’s lights get cut off, you turn the lights back on,” he said. “The rent doesn’t get paid, pay the rent.”

That support allows for students to focus on academic success and for teachers to hold them to high expectations.

“We focus on the social, emotional, and physical needs of our children first and if those are met, then there’s no obstacles and there’s no excuses to getting the work done, and I think that’s really what has put us where we are,” Whittington said. “That’s our bread and butter is the relationships with children.”

Rose Loera, a senior at the school, said close relationships — between students and teachers and between peers — have been a large part of her experience with the early college model. She described moving from Lenoir Early College in Kinston to Pitt ECHS last year as “going from one tight-knit family to another.”

She said the students at Pitt have opened her to new possibilities. Loera got involved in a youth justice program to advocate for issues affecting students and others in the community. She got more involved with student government. She even ran for president with a nudge from her advisor — and won.

“I decided to go big or go home because I’ve never been the student to put myself out there because of … closed-mindedness,” she said. “And then coming here, everything’s different.”

What can be learned from the model? Compassion for students

Though the school’s small size is critical to its success, Whittington said there are some aspects of the school that he thinks, as a former traditional high school principal, could be scalable to a larger setting.

“There’s always a why behind behavior,” he said. “A student cusses you out or wants to skip your class, well there’s a reason. So ask the why. It might be that he or she shares a bed with two siblings and keeps a knee stuck in their back all night and doesn’t get a good night sleep or, at 14, they’re raising their siblings because mom works third shift.”

That cultural shift in teachers, Whittington said, will produce “a lot of bang for your buck.”

“You can’t just ignore behaviors, you can’t just turn a blind eye obviously, but it’s having a little more compassion and understanding for students and the why behind what students do,” he said.

For chemistry teacher Obioma Chukwu, the early college model makes teaching an entirely different experience. Before coming to Pitt, Chukwu had been in a traditional public school setting for 17 years.

Chukwu echoed Whittington’s sentiment — that building a relationship with each student and understanding them personally is what makes this school successful.

“If I could sum it up, it’s personalization and connectivity with the students — that’s what allows them to be extremely successful regardless of socioeconomic background,” he said.

Whittington said the school aims to never send a student back to a traditional setting. “We feel like if we have to send them back to their home school because they’re not getting it done academically, then we haven’t done our job,” he said.

That means a couple students who are now seniors will not graduate with associate degrees, he said, but they will graduate high school. The overwhelming majority of students, he said, graduate with an associate degree and transfer to a four-year university.

Elizabeth Martin, the school’s instructional coach, said a program called Advancement Via Individual Determination (AVID) is a large reason for student success at Pitt — both in high school and through the transition to college. Whether students are just starting out at the school or taking mostly community college courses in their junior and senior years, they participate in a period of AVID. Pitt Community College provides tutors for students struggling with specific subjects, while teachers cover everything from study skills to college admission navigation.

Martin said the “soft skills” are particularly helpful for students whose parents or caretakers have not had the experience of transitioning from high school to a postsecondary atmosphere.

“It demonstrates the importance of not assuming that students know how to be successful students just because they’re in a Cooperative Innovative High School,” Martin said. “I really believe that AVID piece is extremely important to our success.”

She often helps students create note-taking plans during AVID periods. Students report back on how their plans are going and the difference they make in their study habits and their academic performance.

“Invariably, what they’re responding … with is, ‘I can actually remember things. I can find information in my notes,'” Martin said.

Loera said the school has opened doors for her. “It kind of felt like opening my eyes, or taking a blindfold off,” she said. Whether it’s with college classes or personal matters, she knows she is surrounded by people who care. “If you need help, there’s definitely so much help you can get.”

Her newfound empowerment has changed the way she views challenges. To her new responsibility as student government president — a speech at graduation — Loera said, “I’m not much of a public speaker, but I’m up for the challenge.”