Share this story

- In September 1923, the opening of Second Ward High School marked the first public high school for Black students in Charlotte. The State Board of Education celebrated the school’s 100th anniversary with a resolution honoring its legacy.

- "It almost made tears come to my eyes, trying to recall going through a segregated school system with some of the finest educators that ever graced the ground in this community," Arthur Griffin, a Mecklenburg County Commissioner, said of the resolution.

|

|

In September 1923, the opening of Second Ward High School marked the first public high school for Black students in Charlotte.

Last month, the State Board of Education celebrated the 100 years that have passed since the school opened. The Board’s resolution honors “its constructive impact on its students, their families, and the community and for its resolve for creating a place of pride that honored the very best of Black culture and its positive impact on the education experience.”

Board Chair Eric Davis said the resolution marked a new tradition for the Board. At each of the Board’s future biannual planning and work sessions, the Board will now recognize a school in the hosting region that has made a significant impact in its community.

“I can think of no finer school to begin this tradition than right here in Charlotte, with Second Ward High School, located in the heart of this community,” said Davis, former chair of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board.

Second Ward High School closed in 1969, as desegregation and “urban renewal” took place across North Carolina.

Across the country, states responded at varying rates to the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruling that said “separate but equal” standards of racial segregation in public schools were unconstitutional. In Charlotte, a federal judge ruled for the school board to integrate schools in March 1969 – a decision upheld by the Supreme Court in the 1971 Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education case.

At the same time, the federal government gave cities billions of dollars for “urban renewal” projects across the country, under the guise of replacing “slums” with affordable housing. In reality, many people – mostly in African American neighborhoods like Brooklyn in Charlotte – were displaced, with their successful businesses and communities often destroyed.

Second Ward High School was demolished in 1970 after the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools board declared the structure “a hazard,” the Charlotte Observer reported last month. The school board decided to close the other six all-Black schools in the city, too.

Today, only the Second Ward gymnasium is still standing, with that building designated a historic landmark in 2008. Eight years later, Second Ward alumni successfully erected a marker commemorating “the first public high school for Blacks in Charlotte-Mecklenburg” at the site.

As the 100-year anniversary of the school’s opening approaches, school alumni told the Observer they are working hard “to make sure the first-of-its-kind school in the area is never forgotten.”

Davis cited the article at the Board’s May meeting.

“It provides just one small snapshot of the enduring contributions that this institution, Second Ward High School, has made not only to this community, but our state and our nation,” he said.

‘I fell in love with it’

The same year Second Ward opened in 1923, another school – Central High School – opened for white students in the nearby Elizabeth neighborhood.

Second Ward High School, first known as “The Colored High School,” opened with unequal funding and resources in the Brooklyn neighborhood, the then-heart of Black life in the city. The school was closed abruptly by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board after court-ordered integration in 1969.

In the 46 years in between, the school became a beacon of pride and potential for the community, despite overcrowding and limited resources. Before Second Ward opened, Black students could only earn a high school degree at private school or outside the city.

The school’s tiger mascot, according to the resolution, “represented the power, courage, protection, and energy that a school and education could unleash among students and the community.”

State Board of Education member James Ford, who researched Second Ward High School during his doctoral work, presented the resolution to the school’s alumni.

“It gives me great honor to read this resolution,” Ford said. “I heard the story of this school and the communities that it represented – and understated Charlotte history and Black community history that really deserved to be recognized – and I fell in love with it.”

In 1980, the Second Ward High School National Alumni Foundation Association was founded to keep the school’s legacy alive. Since then, the foundation has awarded college scholarships to students in the community. The organization also purchased a house in West Charlotte to serve as a museum and to store archives, research, and memorabilia.

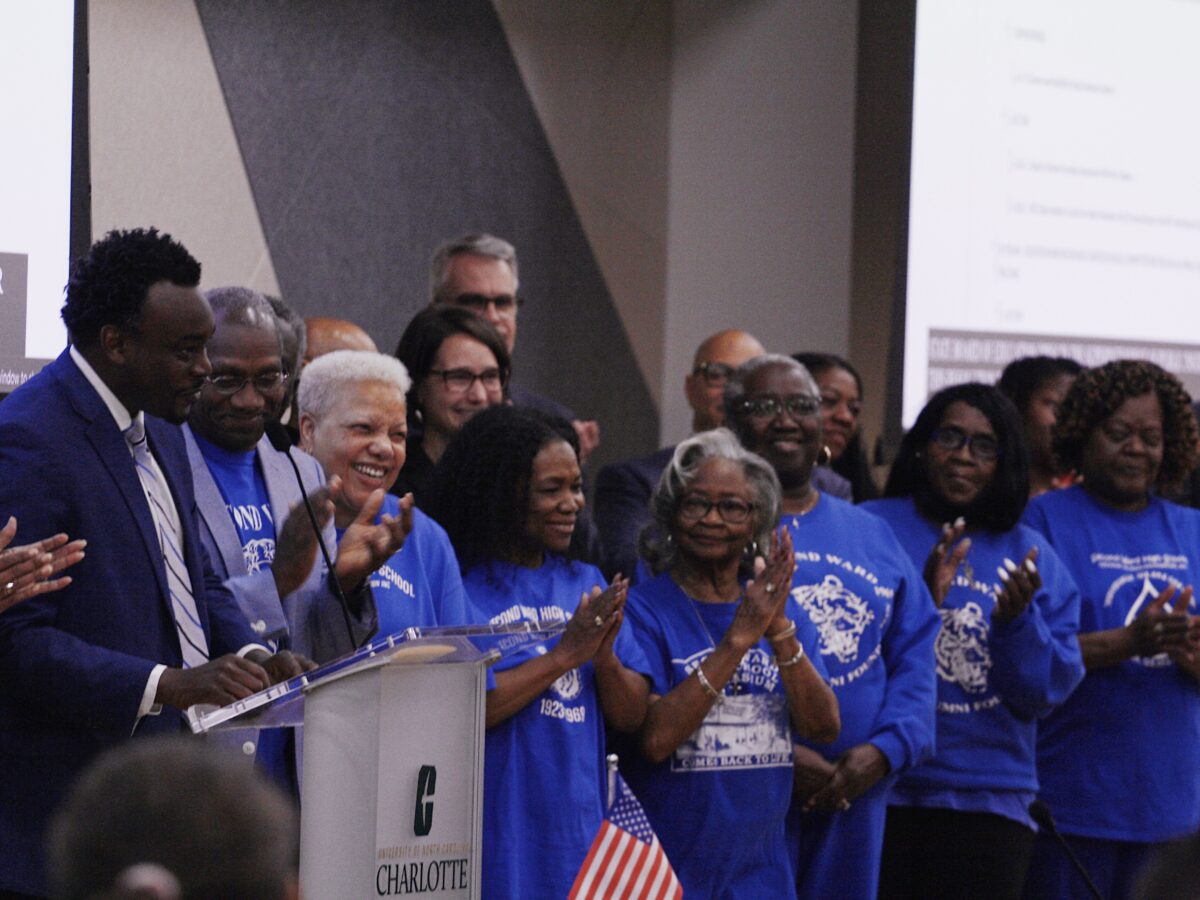

Last month, members of the association joined the State Board of Education for the reading of the resolution. While the association is open to all community members, each of the members present graduated from Second Ward.

Arthur Griffin, a Mecklenburg County Commissioner and former chair of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board, was among Second Ward alumni who accepted the State Board’s resolution. He graduated from the school in 1966.

“As Dr. Ford was reading the resolution, it almost made tears come to my eyes, trying to recall going through a segregated school system with some of the finest educators that ever graced the ground in this community. (Educators) who understood the deep value of education – not only for us as individuals, but also for this great nation of ours, for this state of North Carolina.”

Arthur Griffin, 1966 Second Ward graduate

The resolution specifically recognizes the school’s “teachers and administrators, (who) understanding the school’s unique opportunity for Black children, created a rigorous and disciplined education environment that was also a place of caring and nurturing that developed pride in the school, its communities, and Black culture.”

Those educators were never deterred by limited resources, the resolution reads, but “reached often and unselfishly into their own pockets” to ensure students’ academic and personal needs were met.

Because of such a community, “the long-term positive impact of a short-lived high school” lives on, per the resolution.

There are potential plans to build a new Second Ward High School at the site of the former school, the Observer reported, included in the latest CMS nearly $3 billion bond proposal.

Regardless, Second Ward alumni refuse to let the school be forgotten.

Griffin said the school’s graduates have a long history of working to ensure the school’s legacy of instilling a love of learning in all students continues.

“We join you in your efforts to make sure that education in North Carolina remains strong and effective and available for all the children here in North Carolina,” he told Board members. “I really appreciate the work that you do and will forever cherish this resolution.”

You can read the full State Board resolution here.