Home visiting services across the state are working to help support and uplift parents who are about to have children or who are raising children. A new study revealed the state’s network of programs does not reach 99 percent of North Carolina’s children.

The Jordan Institute for Families, which is housed in UNC-Chapel Hill’s School of Social Work, surveyed agencies on their workforce, programming, site visits, funding, and outcomes. Ninety-three organizations responded. Eighty out of 86 “evidence-based” sites responded. Their responses accounted for 73,088 home visits in 2017 serving 5,300 families and over 400 individuals making home visits or coordinating them. A 2016 study by the National Home Visiting Resource Center estimated that 723,800 children across the state could benefit from services but that only 5,825 families with 6,379 children were reached with home visits.

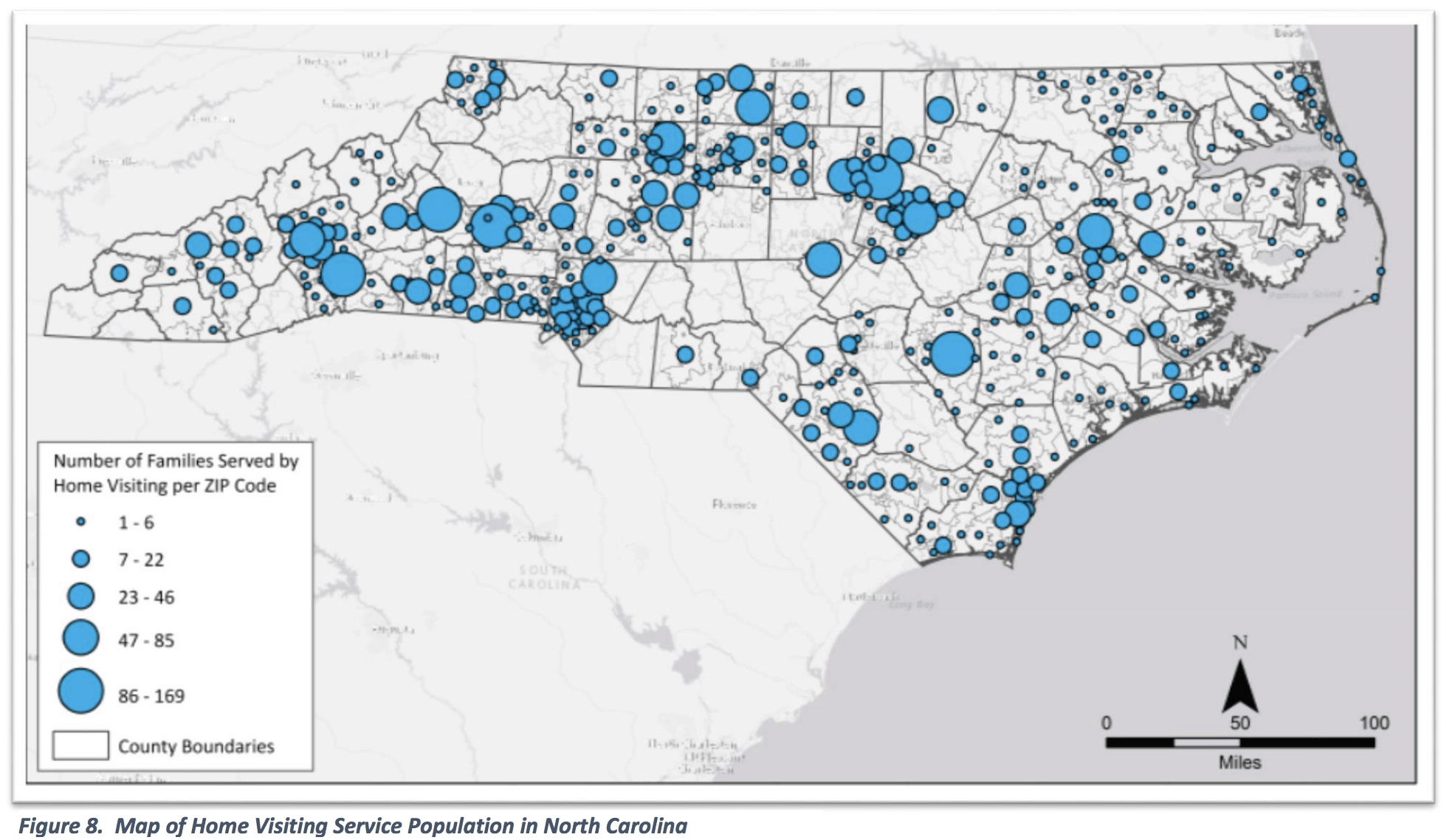

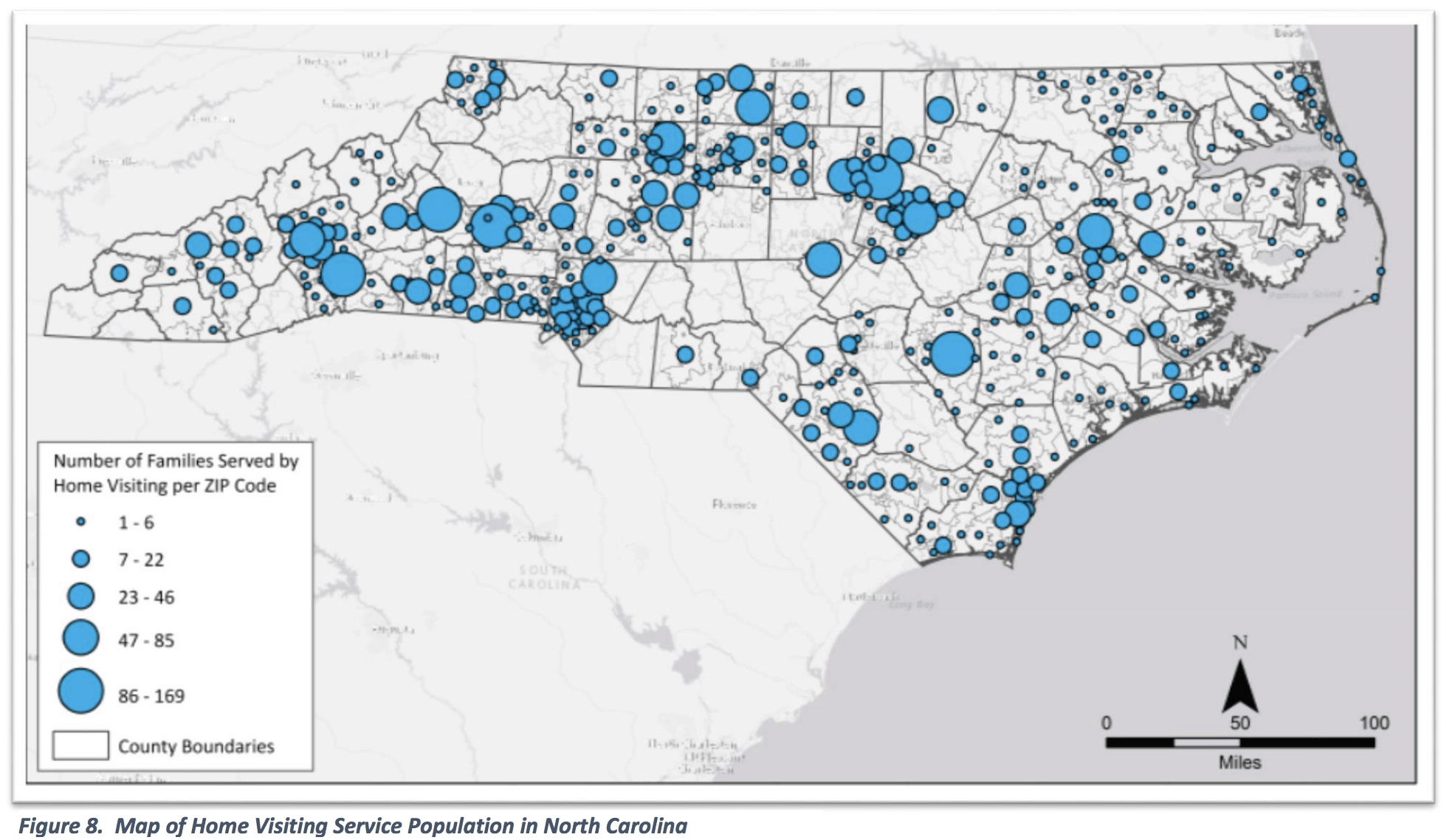

The survey also found that respondents served families in 59 percent of ZIP codes across the state. The report notes that although there are some urban areas of great need and rural areas with high service, rural areas generally have the largest gap in services needed and provided.

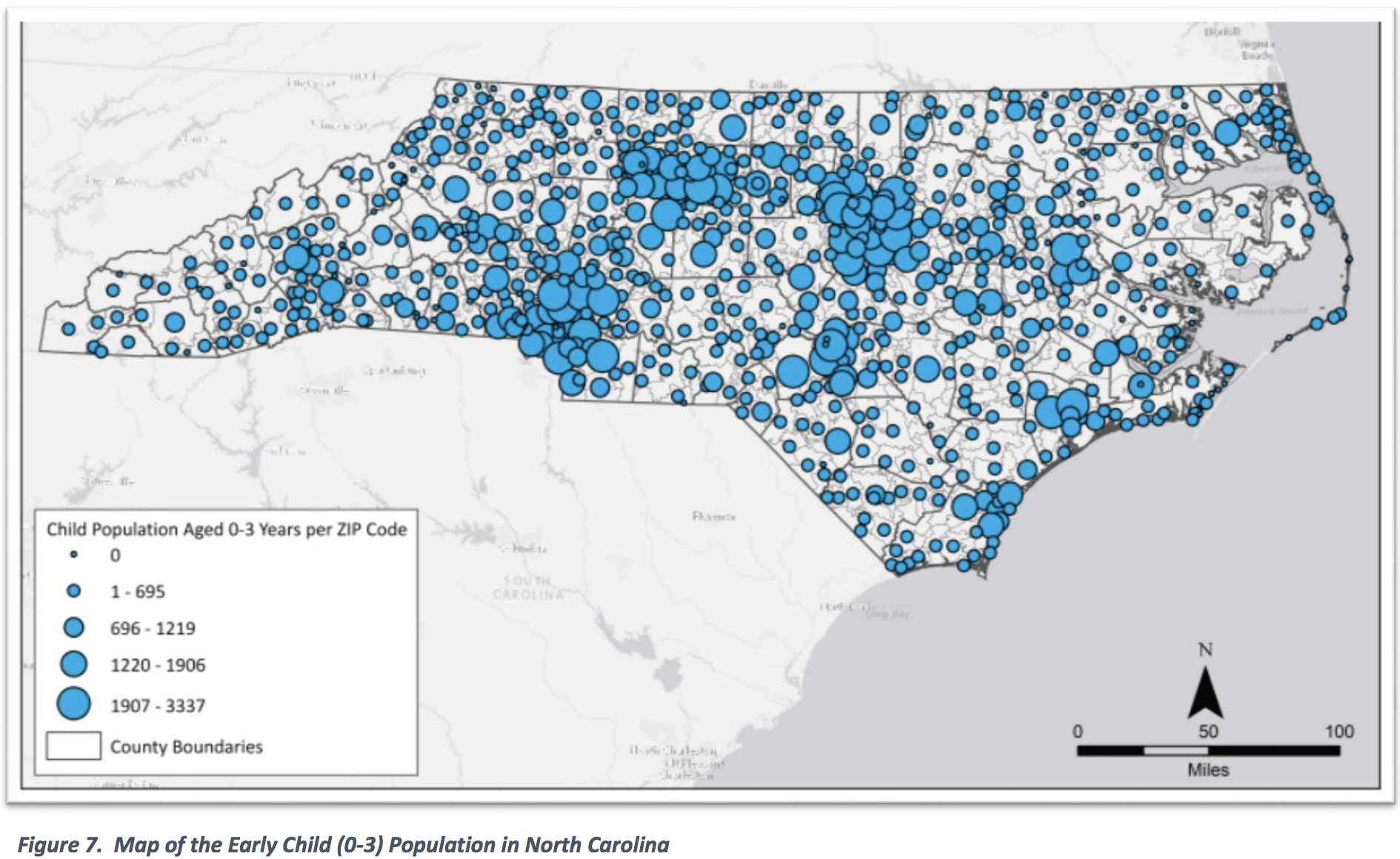

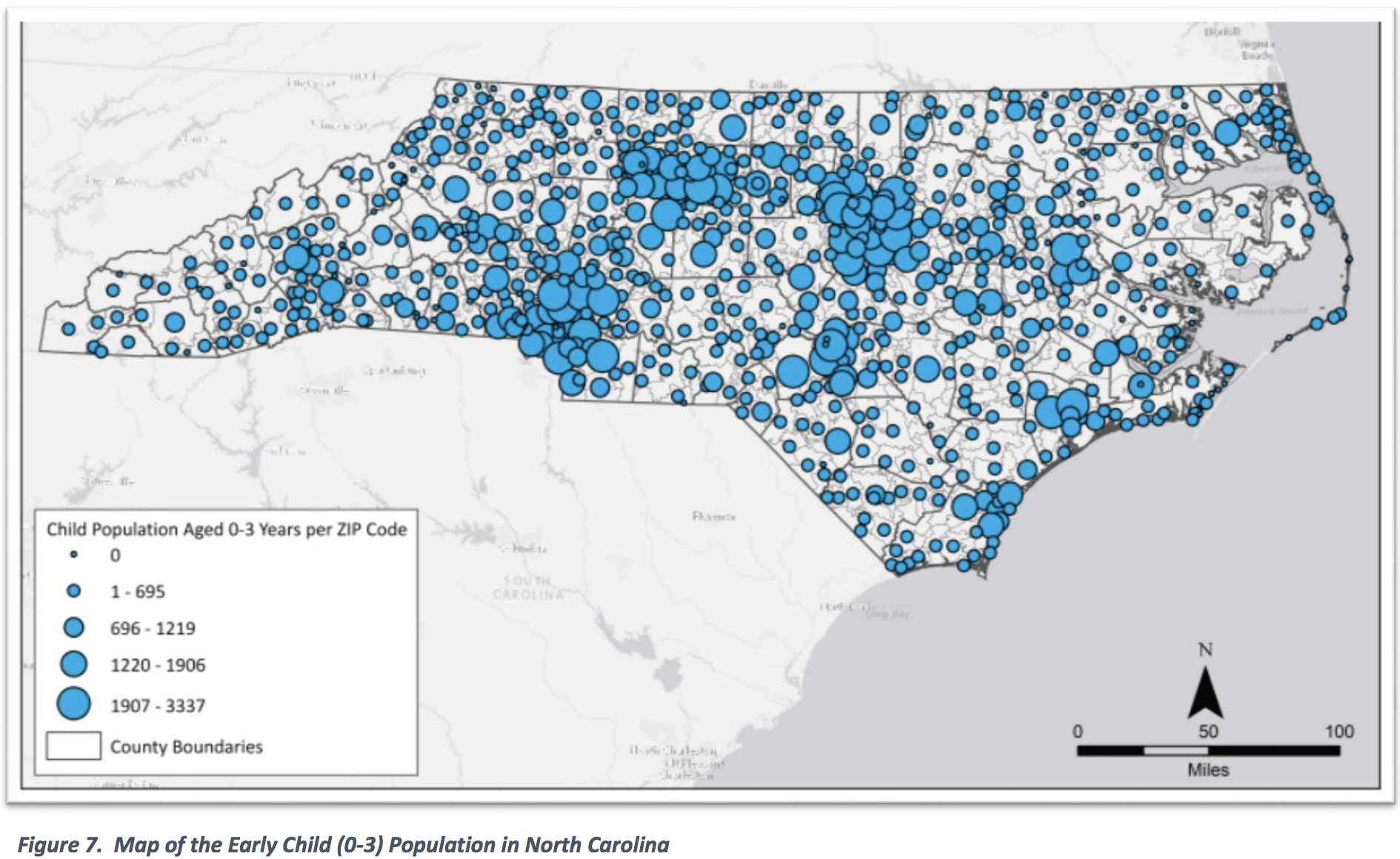

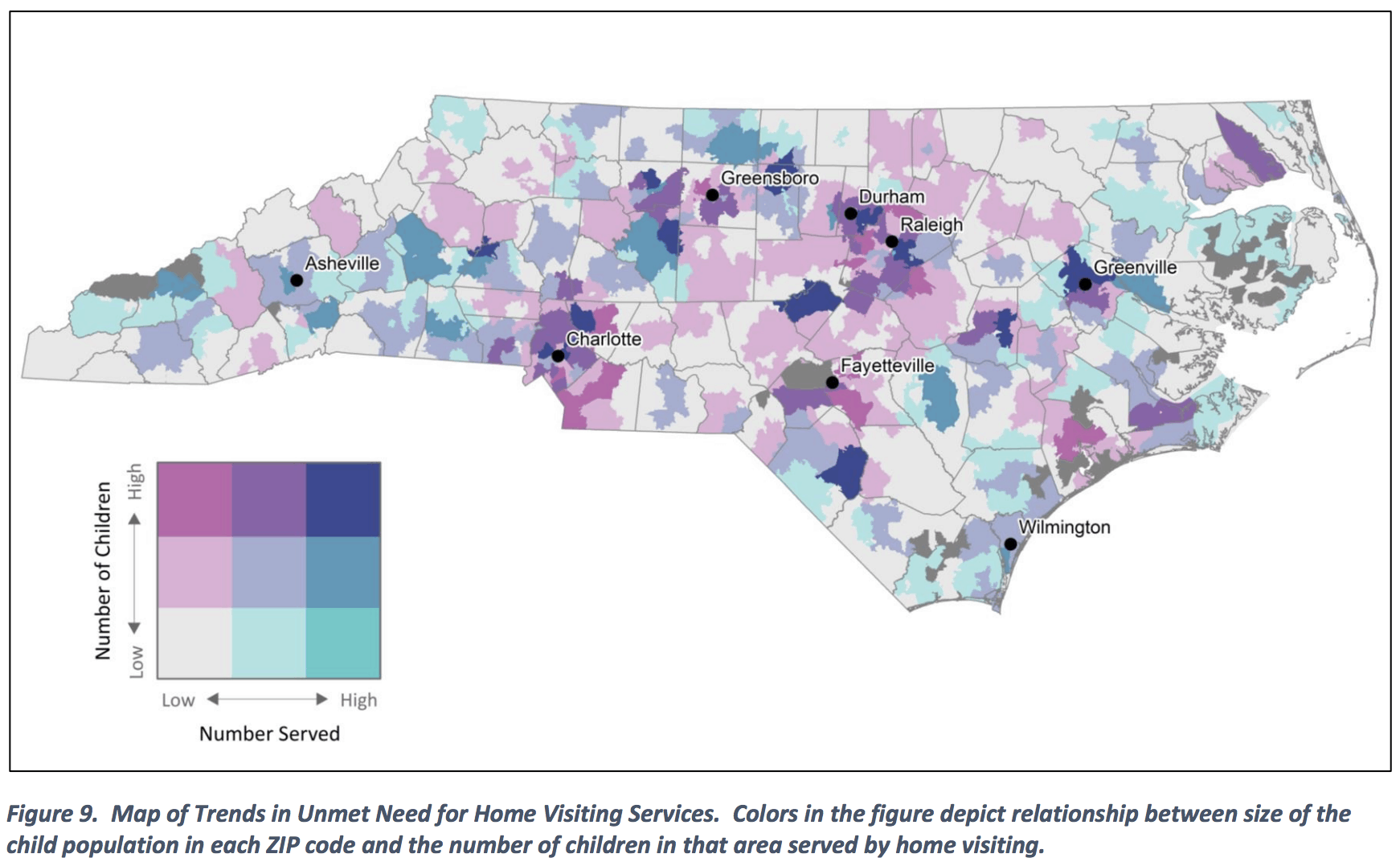

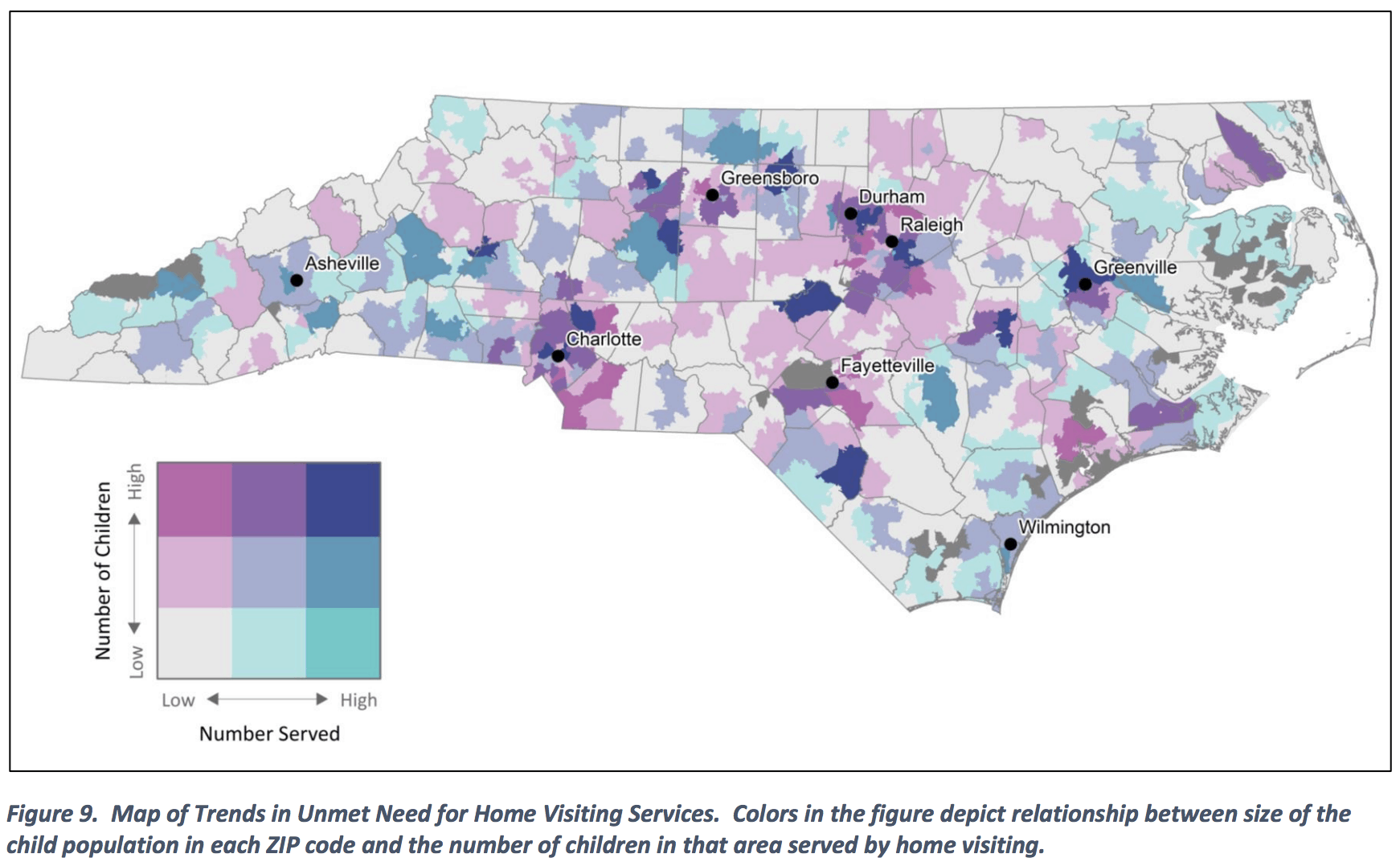

The following three maps, which the report recommends be viewed together, show the population of children from infancy to three years old by ZIP code across the state, the number of families served by home visiting services by ZIP code, and the severity of need across the state — or the “relationship between size of the child population in each ZIP code and the number of children in that area served by home visiting.”

Deb Daro, a senior research fellow and national home visiting expert, spoke Monday in Greensboro to more than 300 early childhood experts and workers on the importance of meeting families where they are. The Home Visiting Summit, hosted by Smart Start, the Jordan Institute for Families, and North Carolina Public Health, was developed to be a place to discuss the report’s results and think of new ways to expand access and collaborate across agencies and systems.

Daro said home visits allow different types of service providers to maximize access in a non-stigmatized fashion. Home visits have potential to introduce healthy relationships into the home and let families know, many of them for the first time, that someone cares, Daro said.

“… It allows us to look at the proximate environment in which kids live,” Daro said. “For young children, for infants, playgrounds are important, parks are important, but for those babies, it’s about the current environment in which their families are caring for them.”

A home visit, she said, often provides more of an authentic look into children and families’ lives and needs than any other strategy.

“When a parent brings someone to a clinical setting, you get one snapshot, but when you go to their home, you see the reality in which their everyday life is framed,” she said. “You can meet the other people that come into that home. You can have a situation to be able to do a more holistic assessment of the well-being of that child and understand what kind of supports families need.”

According to the report, home visiting services vary from program to program but emphasize a positive bond between the home visitor and the family:

“The focus of home visiting activities includes providing prenatal and preventive care, increasing parents’ awareness of appropriate child development, and teaching positive parenting strategies. The common feature shared by all programs is the supportive relationship formed between the home visitor and the family.”

The report also found that 60 percent of programs required a bachelor’s degree for home visitors and that home visitor salaries range from $30,000 to $40,000. Survey respondents were most likely to identify low-income children, families, and teen parents as their targeted populations and least likely to target mothers with maternal depression.

The report, which was funded by the ChildTrust Foundation, the John Rex Endowment, the Winer Family Foundation, and the Duke Endowment, concludes with several recommendations on how to better coordinate the efforts of programs across the state and to strengthen those programs.

“The problem is not the interaction with the families,” said Paul Lanier, one of the primary researchers of the study. “It’s our system we need to work on.”

The report suggests creating a “statewide home visiting leadership structure” to carry out seven recommendations:

- “Identify and implement a sustainable statewide leadership structure that is responsive to local communities.

- Develop a statewide home visiting strategic vision and action plan that is completely integrated with a comprehensive system of care.

- Identify new funding streams to support an integrated family support system anchored by early home visiting.

- Build and support a well-trained, well-resourced workforce by developing a shared educational platform, providing continuing education, creating regional learning collaboratives, and providing skill-building opportunities for core competencies.

- Report annually on a set of common indicators across all programs to provide information about the families served, outcomes achieved, and return on investment.

- Assess community capacity, fit, need, and usability in the selection of models.

- Improve coordination among programs and with other services, including medical homes and social services to comprehensively address family needs.”

Daro, who has looked at home visiting services across the country for decades, addressed how she thinks a system of home visiting could improve, saying that infrastructure is what is missing and that programs should exist in systems that reward innovation, use data to find and scale best practices, and provide connections and referrals between systems.

“I think there’s every reason to believe going forward that while I don’t think home visiting is the panacea or the cure for what ails us, it may be our best bet in terms of improving outcomes for families, providing we think a little more inclusively about how we house these home visiting programs.”

The need for better programming and better infrastructure is one that Daro believes speaks to a larger collective calling to help those in need and recognize human interconnectedness.

“… Public health works best when people are willing to say to other individuals, ‘I care about you, I hear what you need, and here’s what you can do,'” Daro said. “It may be changing your behavior. It may be getting help, but there is some sense that says, this is a social exchange. We’re not put on this earth by ourselves. We’re put here because we’re supposed to be working together.”

Editor’s Note: The Child Trust Foundation is a supporter of EducationNC.