For both experienced and beginning teachers, firsts are important. Firsts are universal and uniting; in fact, it is likely that every teacher can remember his or her first day of school.

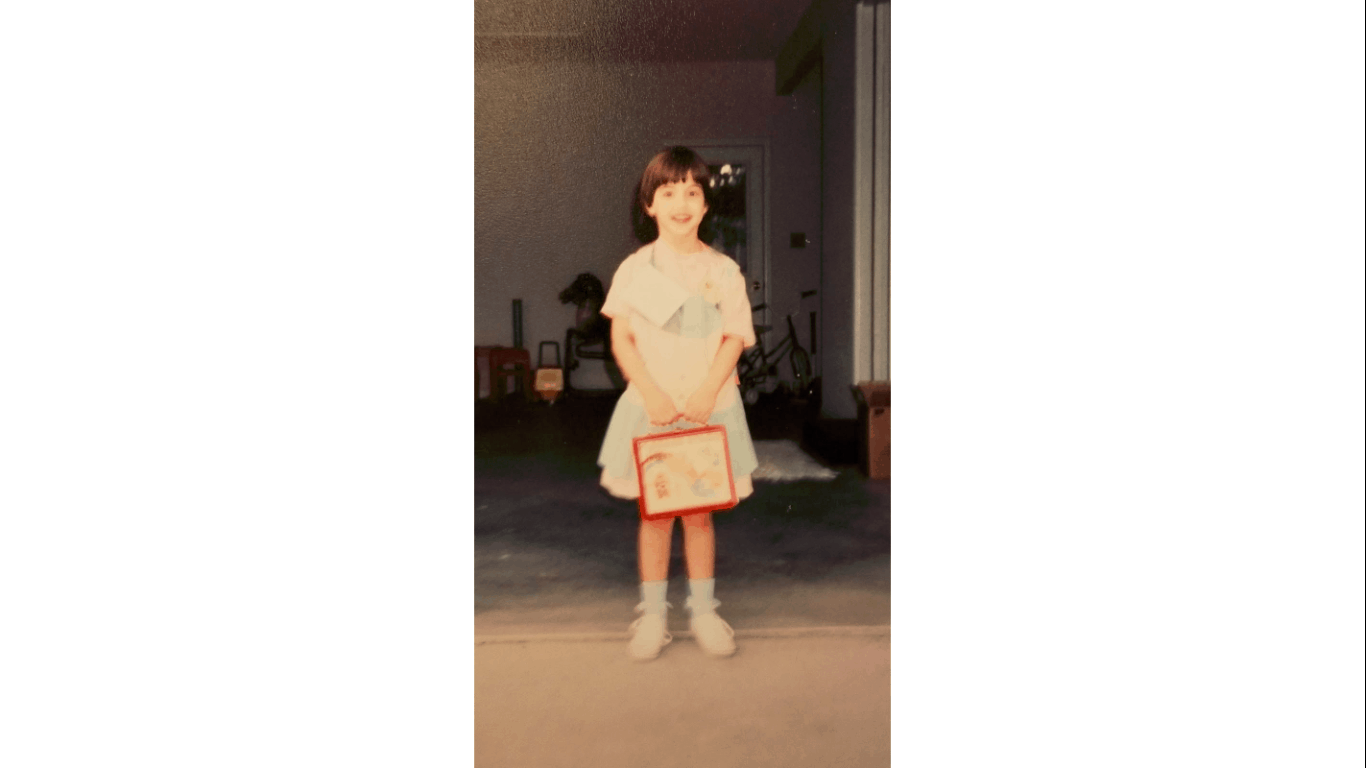

I vividly remember my first day of kindergarten: the Care Bear lunchbox that had a Thermos inside that perpetually smelled like apple juice, and the big blue index card I had to wear pinned to my front that included all of my information. What I do not remember was the look on my face.

It is the look of such joy and such excitement. It is fearless. I loved school from the first day. Every day was something new, and my teachers, Mrs. Davis and Mrs. Forszen, made magic. This expression is genuine, and it is something that perfectly captures the way I feel even now, 10 years in, on the first day of school.

One of the best things we can do for our students is give them this feeling every day beyond the first day. They are still those kindergarteners ready to engage, and so are we. Teachers love school, but what are we doing to make that a reality for our students every day?

When we think of firsts, we are probably thinking more in terms of first days, but I also want to address another important first: first moments.

I remember the first moment I realized that I could trust myself to know how to help students. In my fourth year of teaching, one of my students made me realize that I mattered as a teacher. This student struggled in middle school, and she was figuring herself out when I had her in ninth grade. She was not sure if she was focused on academics or on socializing, but by the end of the year, we had figured each other out. Once we made that connection, her face was just like mine on my first day of elementary school.

On the day of the state test, she was ready. Except she wasn’t, according to the scores I received that afternoon. She earned the lowest possible score, but she would have an opportunity to retest. When I called home, I left a message and then I waited and worried that she wasn’t going to show up. And then she was there. She told me that she almost didn’t come to retake the test because it felt like middle school all over again. She said she heard my message while she was at the dentist and told her mom she wasn’t going in and was just going to repeat ninth grade, not because she was angry, but because she was so afraid of failure. But she then told me that that morning, when she woke up, she wanted to try because she didn’t want me to think she didn’t care. And then she passed with a three on a scale of one to four. And it didn’t matter that it wasn’t her first time.

Before I started teaching, I received my first piece of teaching advice from my mother, who retired in 2017 after 39 years of teaching. She was in her 29th year at that point, and she told me that teaching is the wrong job to get into if you are trying to control something.

And I took that to heart, trying hard year after year to think about change, rather than control, both in and out of my classroom. For any teacher, regardless of years of experiences, we know that there are certainly days that it can feel out of control, or too controlled, but to think smaller is more manageable and more powerful. This first advice was more powerful than my mother realized, and I am reminded of it almost daily.

I remember the first time I doubted myself in the classroom. At year five, six, and seven, I found myself peering into other classrooms, wondering if I was as good at teaching as my peers. All I was seeing was a 30-second glimpse, but I would constantly think, “Does my classroom look like that? Why aren’t my kids looking at me with that same adoring look? Why aren’t my students all leaning in to share a microscope in a very adorable way?” I wanted that level of student engagement, and I was constantly comparing my students compared to the others I saw, or comparing my teaching to what I heard from others. I had turned into the student from my fourth year of teaching who was afraid of failing.

As I continued to reflect on my practice in a way that was harmful instead of helpful, I stumbled on this quote:

“Comparison is the thief of joy. ”

And it clicked. And I knew what I should focus on instead.

In all of my previous “firsts,” I didn’t really have anything to compare myself to — I didn’t have a context. It was me thinking about me. I struggled when I stopped doing that.

Firsts are completely genuine. Regardless of whether you are in year one or in year 31, I can’t emphasize enough the power of first instincts and the power of first moments. Our culture over-values competition, and sadly, our schools have become more competitive over time. Think about standardized testing and school ratings. When we waste valuable energy comparing ourselves to others, we are overlooking potential and the opportunity for personal and professional growth. We might be trying to emulate something someone else is doing, and in the meantime, miss what is right there.

But when we compare ourselves to others, we can lose focus on our students, ourselves, and the trust we should have in our own experiences and joys. We may have been given a way to do things bigger, and better — but perhaps we’ve missed it as our focus is placed on the wrong things.

When I was a beginning teacher, I could not wait to gain experience. However, I now realize how valuable the first years are because there is no fear. The magic of not knowing and trying for the first time is more powerful than the poison caused by doubt and comparison. As an educator, I’ve come to realize that the only thing I should be working on or worried about is being the best version of me I can be; being the best teacher I can be by thinking about what my students need.

Ultimately, I should only focus on my goals and their growth along the way. The decisions I make should benefit my students and myself as an educator; in turn, it is highly likely that both will flourish. We can’t avoid experience. Every year will bring new colleagues, policies, challenges, and successes. But, in order to grow, we can work to stay connected to our earliest experiences as students and educators. And so, rather than comparison, we should live in firsts.