|

|

Highlights

- In fall 2022, EdNC visited all 58 community colleges as part of our Impact58 blitz. As a result of these visits, EdNC identified five indicators that contribute to the financial health of a college and impact how well colleges are able to serve their surrounding communities.

- Those indicators include: 1) individual state budget appropriations, 2) county support, 3) the rate of dual enrollment, 4) foundations and philanthropic support, and 5) receipts from student tuition and other fees.

The N.C. Community College System (NCCCS) served nearly 600,000 students last year in all 100 of the state’s counties — rural, urban, small, large, and in-between.

With yearly budgets ranging from $8 million to $326 million, each college sought to achieve the same mission: providing critical education, training, and workforce opportunities to all North Carolina residents.

The system has an “open-door” policy, meaning all students can enroll and study within the system. Community colleges enroll some of the most diverse student populations — high schoolers, adult learners, working parents, first-generation college goers, and more.

“It goes without saying that having adequate resources is critical to serving our students effectively,” NCCCS President Dr. Jeff Cox told EdNC. “We need to look critically at how well all our colleges are funded to meet our students’ needs fully.”

State appropriations make up the majority of community college funding, based largely on enrollment. This year’s state budget allocated nearly $1.9 billion to the NCCCS in 2023-24 — with nearly $1.5 billion in state appropriations, and more than $400 million in receipts. However, the reality of financial health at our community colleges is much more complex.

You can read more about how community colleges are funded in this EdExplainer. You can also read about the system’s efforts to modernize the current funding model here.

During EdNC’s Impact58 tour, community college leaders spoke about many factors that contribute to a financially healthy community college. EdNC identified five indicators that contribute to how well colleges are able to serve their students and communities:

- Special appropriations in the state budget for individual community colleges. Do colleges have good relationships with their legislative delegation? Does their legislative delegation have influence within the General Assembly? This matters for how colleges can access funds for things like new programs and equipment.

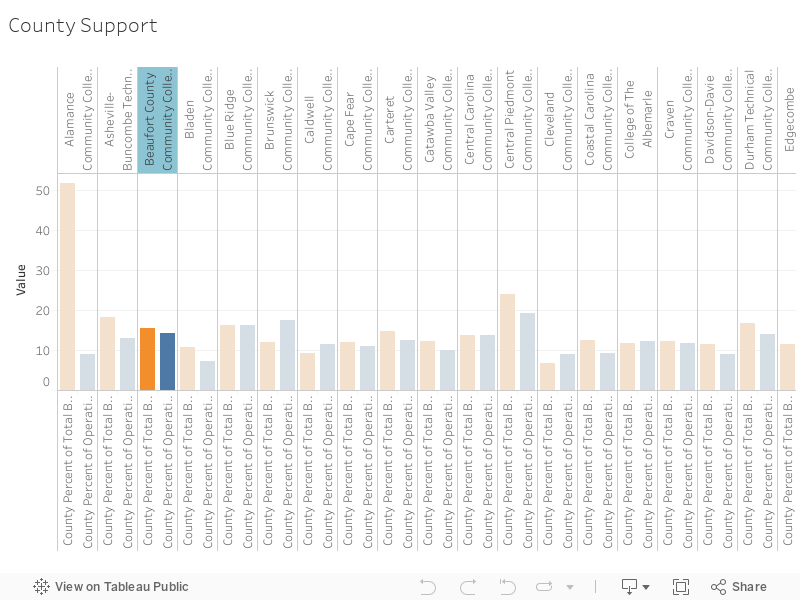

- County support. The county is responsible for financially supporting the “physical plant” of the college. Varying levels of county wealth, along with college-county relationships, influence how much county support colleges get for new construction and initiatives.

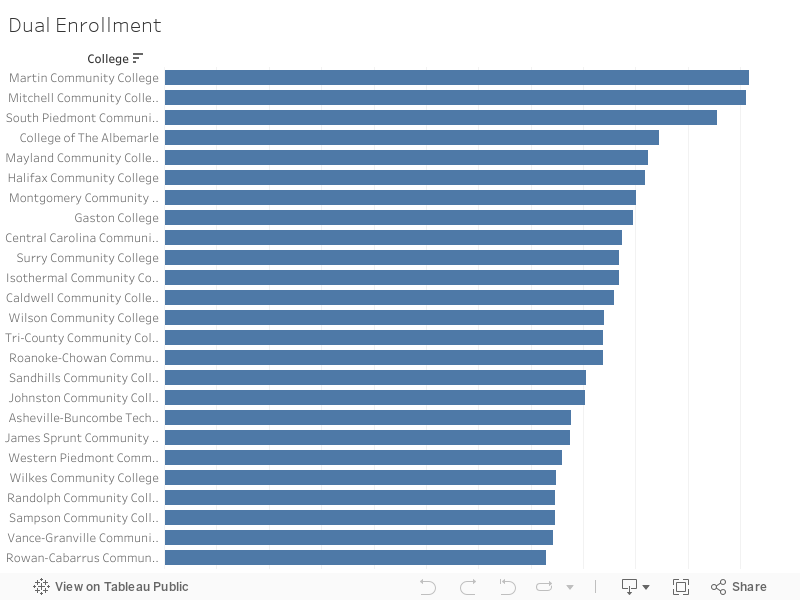

- The rate of dual enrollment. How are colleges leveraging dual enrollment, along with relationships with their K-12 school district(s)? Dual enrollment has contributed significant FTE for some colleges, particularly in rural counties with declining population trends.

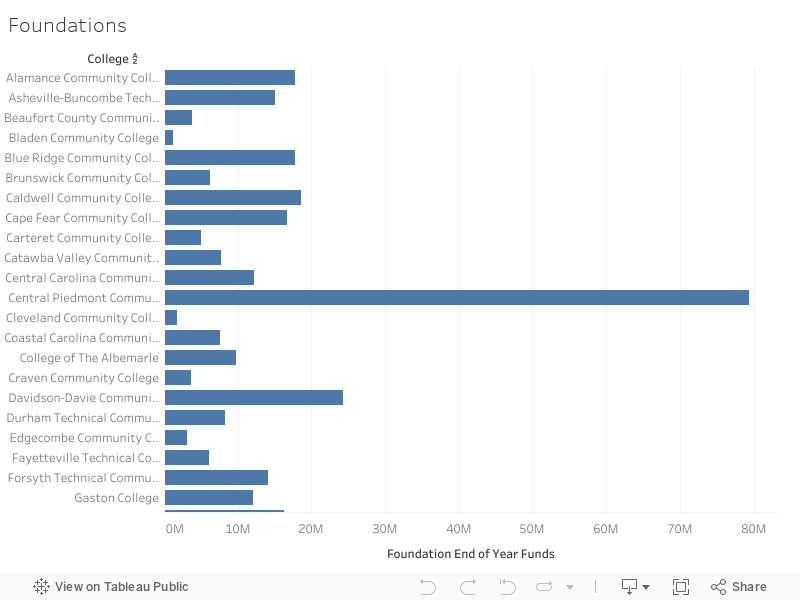

- Foundations and philanthropic support. Are college foundations successful at raising outside funding? The scale of innovative initiatives at colleges is largely influenced by access to philanthropic support through foundations and grants.

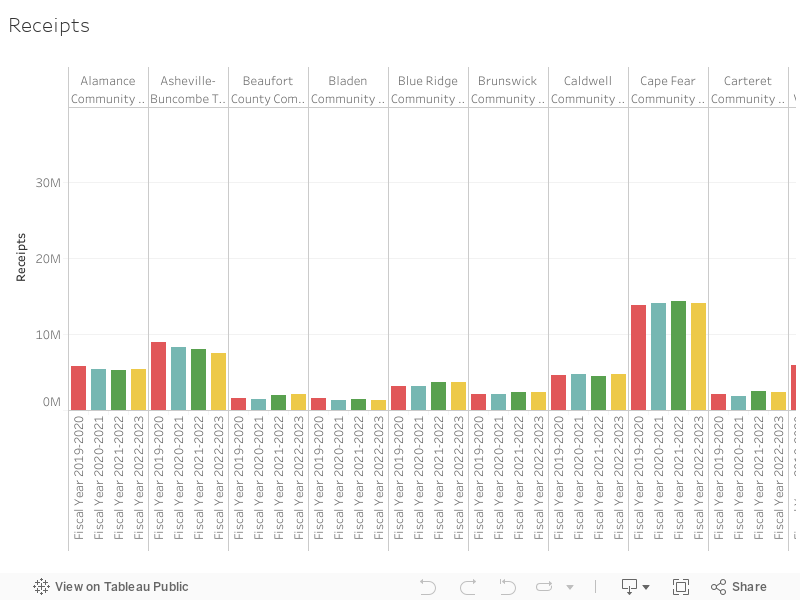

- Receipts from tuition and fees. All 58 community colleges take in student tuition and fees and those are by law deemed state funds. In 2023-24, 21.5% of the total state budget for community colleges is funded through expected receipts.

Taken together, these indicators also greatly influence a college’s ability to access funds for things like student scholarships and new innovative workforce programs. Successfully funding both is particularly important as the state works to meet its 2030 educational attainment goal and demand for skilled workers.

Without additional funding, community college leaders told EdNC, it’s difficult for colleges to respond effectively or with the creativity and flexibility required.

“All of these resources, collectively, are essential in helping us do the work that we do,” said Halifax Community College President Dr. Patrena Elliott.

Following our Impact58 tour, EdNC decided to dig more deeply into these indicators.

EdNC analyzed systemwide data on special budget appropriations for colleges, county funding, dual enrollment, college foundations, and tuition receipts. We spoke to about a dozen community college leaders, some of whom are quoted here, about how these indicators collectively contribute to more financially flexible, stable colleges.

Here’s what we learned.

Special budget appropriations for colleges

The new budget included $100 million nonrecurring in each year of the biennium for new construction and repairs of facilities at nearly 60% of the state’s community colleges. This marks an unprecedented number of individual allocations to community colleges, several NCCCS leaders told EdNC.

These individual college allocations largely fund new facilities and equipment for workforce and health care programs across the 58 colleges. Another group of allocations, which largely went toward health care related programs, were funded through federal Medicaid expansion dollars.

“We appreciate the significant investments made in this year’s budget, which will undoubtedly enhance our ability to empower students and bolster workforce development across North Carolina,” Cox said in a statement.

At Lenoir Community College, which received $5 million for capital projects, President Dr. Rusty Hunt said such allocations are really important. Capital allocations in the budget help fund projects that otherwise would never be able to be funded in some lower-wealth counties.

Importantly, he said, many allocations also provide “seed money” for colleges to start high-cost programs they might otherwise not be able to afford.

“But once they get money to get started, the FTE that it generates will then sustain the program,” Hunt said. “So I think that’s also important to understand as far as the funding goes, and why even some of that non-recurring funding is important in creating additional recurring funding in the future in additional FTE.”

Out of 58 colleges, 34 received individual capital allocations in the latest budget while 24 did not. Of the 24 that did not receive individual capital allocations in this budget, 11 colleges received individual allocations in the last biennium budget.

In addition, 14 community colleges received allocations totaling more than $275 million over the biennium from federal Medicaid dollars for health care related programs in the budget.

Generally, the majority of individual allocations in the budget go toward funding capital projects, so a lack of allocations could mean no request was made.

As of 2021, state law includes a matching requirement for capital funding to new construction projects in Tier 3 counties, as provided in the annual ranking by the Department of Commerce. Some colleges in such counties also might not make requests due to lacking the matching funds.

But political relationships are also a factor.

There is a Republican supermajority in the General Assembly this year, following Rep. Tricia Cotham’s switch to the Republican party last April. In addition to the influence of Republicans in the General Assembly, the influence of Republican representatives within their caucus also matters. Here is a list of the lawmakers who served on the conference committee last long session.

For community colleges, building relationships with lawmakers in their delegation — and with influential members – is important. Colleges must build particularly strong relationships with their representatives, as their senators cover multiple counties.

In Haywood County, for example, the community college submitted a joint legislative request with the town, county, and school system to the General Assembly.

The college successfully received $3 million nonrecurring for job training programs that support the community following the closure of the Canton Mill. The budget included an additional $3 million to the college for renovations and improvements for a consolidated workforce and industrial training site.

“These opportunities can be transformational,” Haywood Community College President Dr. Shelley White said of the allocations. “They obviously hinge on relationships, again, and shared vision for the future of colleges.”

In addition to speaking with their local delegation, the Haywood group also spoke to other state lawmakers about their community’s needs following the mill closure. Strengthening legislative relationships requires persistence, White said.

“For a small county, and small college, we were able to successfully receive $6 million,” she said. “It’s an incredible investment and something that we’re very excited to see the legislature support during this critical time for our community.”

Cleveland Community College, located in House Speaker Tim Moore’s district, was allocated $17.025 million for capital improvements or equipment in this year’s budget and nearly $2 million in the 2021-23 budget.

Cleveland County is represented by two other Republicans in the General Assembly — Sen. Ted Alexander and Rep. Kelly Hastings.

In Sept. 2022, Cleveland Community College held a naming and ribbon cutting ceremony for its new advanced technology center, “Speaker Tim Moore Advanced Technology Center.”

Below you can find a list of the top individual college allocations in the budget this year, along with the legislative delegation for that college.

There are five Democratic representatives included on this list. Three of those Democrats — Reps. Garland Pierce, Shelly Willingham, and Michael Wray — were swing voters in this year’s legislative session.

| College | Allocation | County & Delegation |

| Gaston College | $60 million for capital improvements or equipment at a health science education and simulation center. | Gaston: Reps. Kelly Hastings (R), Donnie Loftis (R), John Torbett (R), and Sens. Ted Alexander (R) and Brad Overcash (R). Lincoln: Rep. Jason Saine (R) and Sen. Ted Alexander (R). |

| Cape Fear Community College | $30 million for health program capital improvements, $7 million for a new research vessel to replace the Cape Hatteras vessel, and $4 million for the Surf City campus expansion and related capital improvements or equipment. Another $500,000 to fund a partnership program between Cape Fear Community College (CFCC), New Hanover County Schools, and Pender County Schools. | New Hanover: Reps. Deb Butler (D), Ted Davis, Jr. (R), Charles Miller (R), and Sens. Michael Lee (R) and Bill Rabon (R). Pender: Rep. Carson Smith (R) and Sen. Brent Jackson (R). |

| Caldwell Community College and Technical Institute | $39 million to assist with construction costs related to a new health science building. | Caldwell: Rep. Destin Hall (R), and Sens. Ralph Hise (R) and Dean Proctor (R). Watauga: Reps. Destin Hall (R) and Ray Pickett (R), and Sen. Ralph Hise (R). |

| Isothermal Community College | $30 million for a new health sciences building. | Polk: Rep. Jake Johnson (R) and Sen. Timothy Moffitt (R). Rutherford: Reps. Jake Johnson (R) and Tim Moore (R), and Sen. Timothy Moffitt (R). |

| Wilson Community College | $30 million to help construct a workforce training center, + $4.2 million for capital funds. | Wilson: Sen. Buck Newton (R) and Rep. Ken Fontenot (R). |

| McDowell Technical Community College | $25.25 million for a new health sciences and public safety complex. | McDowell: Reps. Dudley Greene (R) and Jake Johnson (R), and Sen. Warren Daniel (R). |

| Sandhills Community College | $25 million for a new vocation career path early college high school. At full capacity, the new early college will be able to serve 400 students. | Hoke: Rep. Garland Pierce (D), Sen. Danny Earl Britt, Jr. (R). Moore: Reps. Neal Jackson (R), Ben T. Moss, Jr. (R), John Sauls (R), and Sen. Majority Whip Tom McInnis (R). |

| Brunswick Community College | $25 million for workforce development center and public safety center capital projects. | Brunswick: Reps. Frank Iler (R) and Charles W. Miller (R), and Sen. Bill Rabon (R). |

| Stanly Community College | $13 million for capital projects, + $8.25 million for a basic law enforcement training building and associated road improvements. | Stanly: Rep. Wayne Sasser (R) and Sen. Carl Ford (R). |

| Robeson Community College | $21 million for capital improvements to the health career center, $50,000 for technology upgrades and related equipment. | Robeson: Reps. Brenden Jones (R) and Jarrod Lowery (R), and Sen. Danny Early Britt, Jr. (R). |

| Pamlico Community College | $20 million for the construction of an allied health center, $650,000 to support the college’s prison education program. | Pamlico: Rep. Keith Kidwell (R) and Sen. Norman Sanderson (R). |

| Coastal Carolina Community College | $20 million to complete construction of a math and science building. | Onslow: Reps. George Cleveland (R), Phil Shepard (R), Carson Smith (R), and Sen. Michael Lazzara (R). |

| Cleveland Community College | $17.025 million for capital projects. | Cleveland: Reps. Kelly Hastings (R) and Tim Moore (R), and Sen. W. Ted Alexander (R). |

| Wayne Community College | $17 million for capital projects. | Wayne: Reps. John Bell (R) and Jimmy Dixon (R), and Sen. Buck Newton (R). |

| Rowan-Cabarrus Community College | $9 million for capital projects, + $5.5 million for parking and sewer infrastructure for the North Campus. | Cabarrus: Reps. Kristin Baker (R), Kevin Crutchfield (R), and Diamond Staton-Williams (D), and Sens. Todd Johnson (R) and Paul Newton (R). Rowan: Reps. Kevin Crutchfield (R), Julia Howard (R), Harry Warren (R), and Sen. Carl Ford (R). |

| Roanoke-Chowan Community College | $15 million for the construction of a new health sciences building. | Bertie: Rep. Shelly Willingham (D) and Sen. Bobby Hanig (R). Hertford: Rep. Bill Ward (R) and Sen. Bobby Hanig (R). Northampton: Rep. Michael Wray (D) and Sen. Bobby Hanig (R). |

| Sampson Community College | $15 million for allied health care capital improvements. | Sampson: Rep. William Bisson (R), and Sens. Jim Burgin (R) and Brent Jackson (R). |

Seven of the above colleges also received individual allocations for the 2021-23 budget.

- Caldwell Community College received $23 million for a health science building, $5 million for an occupational training facility, and $1.6 million for equipment.

- Robeson Community College received $19 million for a workforce development building and $1.4 million for a generator.

- Brunswick Community College received $15 million for capital projects.

- Gaston College received $5 million for PPE and $2 million for cybersecurity.

- Cleveland Community College received $1.5 million for capital projects and $450,000 for a law enforcement training center.

- Sampson Community College received $1.5 million for a truck driver training project.

- McDowell Tech received $1 million for public safety training.

You can view the full list of individual college allocations on EdNC’s website.

County funds

State law requires the local tax-levying authority — counties — to provide “as appropriate, adequate funds to meet the financial needs” for facility-related items at community colleges.

County funding makes up an average of about 15% of college operating funding, NCCCS Chief Financial Officer Dr. Phillip Price said at a September State Board of Community Colleges meeting.

“These allocations certainly differ among colleges,” Cox said.

The NCCCS collects annual information related to each college’s county funding. You can find that information for the 2022-23 fiscal year on the system’s website.

The system does not conduct any analysis on that information, according to Cox.

“And we at the system level do not currently try to mitigate the variance in local support for our colleges,” he said. But, “Local colleges’ access to local funds, whether provided by their counties or through other means — philanthropy, local business and industry, grants — can have a significant impact on colleges’ ability to serve their students.”

In 2022-23, counties contributed more than $315 million toward college operating budgets, which represents a little over 12% of college operating budgets. Counties contributed more than $606 million toward total college budgets, which includes both capital contributions and operating budgets. This represents 19% of total college budgets.

Those total county contributions reflect a 12.22% increase since 2021-22, per NCCCS data. At the same time, total college budgets decreased a little more than 3% — further reflecting the importance of county funding sources.

The average county contribution toward a college’s operating budget in 2022-23 was $5.45 million, according to EdNC’s analysis. The median contribution was about $3.2 million. Among all 58 colleges, county contributions to colleges’ operating budgets ranged from $717,000 to $43.2 million.

The average county contribution toward the total budget in 2022-23 was $10.5 million, per EdNC’s analysis. Those county contributions to colleges’ total budgets ranged from $717,000 to $121 million. (Not all colleges received capital funding from counties in 2022-23.)

While access to capital project funding is critical for college repairs and growth, county contributions to a college’s total budget can vary significantly from year to year as capital projects ebb and flow. The contribution to operating budgets is typically more stable.

The NCCCS county funding report doesn’t break down county contributions by the different counties served by a college. Some community colleges only serve one county, but many serve multiple.

Haywood Community College only serves Haywood County, which White said has been “very supportive” of the college. The county has a quarter cent sales tax that is directed toward the college’s capital needs.

“That’s been very helpful to the campus over the long term,” White said. “And I’ve been given every indication that that’s intended to continue.”

White emphasized that a good working relationship with the county goes beyond budget negotiations – highlighting efforts to partner with the county’s health and economic initiatives, too. Of course, she said, working with only one county, versus several, makes investing in such relationships “simpler.”

“For our colleagues who work with multiple counties, not only is their time stretched among those multiple counties, but also the resources, and doubling, tripling, quadrupling those relationships and the networking and the partnering,” she said. “I mean it adds a whole other layer of complexity.”

Because county funding for capital projects is largely generated from a county’s tax base, there often is a large discrepancy between what wealthy and low-income counties can give to colleges.

For community colleges that serve more than one county, investment depends on many things — tax base, relationships, and how counties perceive access to community college resources.

Lenoir Community College serves three counties: Greene, Jones, and Lenoir. Hunt said it’s crucial for a college to engage all of its service regions in order to build partnerships and serve more students.

“Wealthier counties can obviously afford to do more for their colleges than some of the other counties, and particularly rural counties, can do in many cases,” Hunt said. “I think it’s much more important that you develop partnerships in counties who have challenges and you figure out other ways.”

Generally, he said, urban counties are more likely than rural counties to propose bonds to pay for large college capital projects or have an additional sales tax in place to support the college’s growth.

While most rural counties can’t offer such funding streams, Hunt said it means colleges just have to be more creative. As a practice, he never asks his county commissioners for money he isn’t willing to try to find from other funding sources or partners.

In addition to searching for external funding sources and leveraging third-party resources, Hunt said partnering with local agencies to “streamline our needs” can also help. He specifically cited combined or shared facilities, like one between the college and local school system for transportation vehicles.

“It’s (county funding) an incredibly important funding stream for our colleges,” Hunt said.

At Halifax Community College, which serves Halifax and Northampton counties, Elliott said county funding supports the very infrastructure of the college.

“That can’t be overstated,” she said.

Even in wealthier counties, she said, county governments support multiple organizations and operations within the county, meaning there are never enough dollars to fully fund every need.

When working with multiple counties, colleges also have to account for the fact that the size of their service area might differ across counties.

“You’re not going to be able to address all the needs at once, but you can work collaboratively to address it over time,” Elliott said. “I really see it as a great opportunity, because regardless of the contributions across counties, at the end of the day, you still have county support that helps to position you to help the students be successful.”

Dual enrollment

North Carolina’s State Board of Education and State Board of Community Colleges established the Career and College Promise (CCP) program in 2011 to connect high school students to college and career goals. Through the program, high school students can earn college credits for free — with tuition paid for by the state.

“From an overall perspective, CCP is great,” Hunt said. “It’s great, obviously, for the college. It’s great for, I think, for the high schools themselves, and for their students, to have access to higher education earlier on. When I was growing up, we didn’t have access to that.”

CCP includes three pathways: Career and Technical Education (CTE), college transfer, and Cooperative Innovative High Schools (CIHS), which includes early and middle colleges.

In 2022-23, the NCCCS served approximately 78,000 dual enrollment students across the state, according to system data. North Carolina’s CCP students outperform the general student population at community colleges, system data shows. A college’s CCP population is also often more diverse than the college’s overall student population, Hunt said.

Pamlico Community College had the fewest number of dual enrollment students at 150, whereas Central Piedmont Community College had the most at 4,804. At both of these schools, dual enrollment students made up about 10% of the college’s headcount.

Across the system, dual enrollment made up about 13.6% of headcount on average in 2022-23, per EdNC analysis of total and dual enrollment headcounts. Those percentages ranged from roughly 6% at Durham Technical Community College and Fayetteville Technical Community College to over 22% at Martin Community College.

Hunt said there is a higher percentage of dual enrollment students at many smaller, rural colleges. At Lenoir Community College, he said dual enrollment typically makes up about 35-40% of its curriculum enrollment.

Across the state, 12% of high schoolers are dually enrolled, per a 2020-21 NCCCS dashboard — ranging from 4% to 47% when broken down by county.

While large, urban counties often have a smaller percentage of dual enrollment students, they provide other opportunities for college credit, like AP or IB courses. You can view the rate of AP course participation by school district per year on DPI’s website by downloading the yearly test report data.

“Large colleges serve many dual enrollment students, but it makes up a smaller number,” said Dr. Dale McInnis, president of Richmond Community College. “I don’t think there is an ideal dual enrollment percentage, but everybody has to find that sweet spot for where they’re located.”

There are a few factors for colleges and presidents to consider, McInnis said.

First, colleges want to consider how the percentage of dual enrollment students impacts college culture overall. Classes usually work better with “a good mix of high school students and adult students,” he said.

Colleges also must ensure they are aligned with their local school systems and high schools in order to smoothly onboard and support students. One area in which many colleges are continuing to work to provide better access for high school students is transportation, McInnis said.

Finally, most CCP students are part-time students, meaning it typically takes more CCP students for colleges to earn one FTE. A full-time student must take 16 credits both semesters, while dual enrollment students usually take half that amount or less.

From a resource standpoint, this can be a big deal for colleges, McInnis said. CCP students are still on campus, needing and using student services whether they take one class or five.

“But when we talk about the impact of these students on the formula, it’s all positive,” he said. “There’s no downside to dual enrollment and early college students. At the end of the day… these are the same students we were fighting to recruit when they graduated, and now we’re getting them in high school.”

Here is a look at the rate of dual enrollment across the 58 community colleges, according to the percentage dual enrollment headcount made up of total headcount in school year 22-23.

You can read EdNC’s report on the benefits of CCP on our website.

Foundations and philanthropic support

College foundations are another important piece of the financial health of community colleges.

Foundations, which are 501(c)(3) nonprofits, serve as a flexible arm to colleges — partnering with private organizations, testing pilots, and investing in innovation.

“Foundations are philosophically the engine of partnerships,” said Katie Loovis, the first full-time executive director of the North Carolina Community Colleges Foundation, Inc. “In the times ahead, we will need them even more.”

Foundations can also help to supplement college budget needs not met by county and state funding, Halifax Community College President Dr. Patrena Elliott said. At Halifax, the foundation consistently provides student scholarships and funds for various institutional needs.

“The role of the foundation is very important,” she said.

Each of the 58 colleges has a foundation, in addition to the system-wide foundation. Together, the 58 college foundations have nearly $608 million in assets, according to data EdNC pulled from each foundation’s most recent 990 form.

Foundation assets vary widely — from just over $262,000 to nearly $80 million.

Among college foundations, 990 forms suggest a wide disparity in how much of funds actually goes to college programs and scholarships. Sometimes nonprofits spend more in overhead costs for one or two years to build capacity, meaning you have to look at an organization over time to truly see how it spends its money.

Revenue after expenses at college foundations also varied widely. On average, revenue after expenses was $804,570, per EdNC’s analysis. Across all 58 foundations, that number ranged from -$2 million to $11 million.

For colleges that lost revenue in their most recent 990 form, many lost money due to loss of investment or investment management costs. Again, a year-to-year look at these costs is needed to get a more accurate picture of a foundation’s financial stability.

At least 76% of the Central Piedmont Community College Foundation’s expenses went toward college programs and grants, according to the 990 form’s statement on functional expenses. Founded in 1968, it is the largest foundation in the system.

“It’s a critical relationship,” said Vanessa Stolen, Central Piedmont’s associate vice president of institutional advancement. “The foundation extends the college’s reach.”

Lisa Schlachter, the college’s vice president of institutional advancement, serves as the chief fundraising officer and as director of the Central Piedmont Foundation. She said it’s crucial that the foundation is “truly in alignment” with the college, while also educating the college about the different practices that a nonprofit has.

The foundation also works with a charitable giving council to review its bylaws and practices.

“We recognize we are responsible for a significant amount of funding, and we want to be the best stewards of that that we can be,” Schlachter said.

The foundation can help fund needs quickly and innovatively, Schlachter and Stolen said.

Jeff Lowrance, Central Piedmont’s vice president of communications, marketing, and public relations, gave an example of how the foundation has been critical to the college.

A few years ago, Central Piedmont decided not to participate in the direct federal loan program. Lowrance said the college did not want students to take on any debt to attend. In response, the college turned to the foundation for an increase in student scholarship support.

Today, the foundation gives around $3 million annually toward student scholarships, Lowrance said.

“Our foundation board and donors are just so passionate and proud of the work Central Piedmont is doing,” Schlachter said. “I’d be remiss if I didn’t say how grateful we all are to help students in our community through the generosity of our donors.”

Grant-writing and staff capacity

Along with the indicators explored above, several presidents also cited the importance of grants, which can come from state and federal funds, along with private organizations.

However, grants present a double-edged sword, community college leaders told EdNC. While grants can offer transformational opportunities to smaller colleges in particular, these colleges often lack the capacity to seek grants.

“Many of our colleges rely on external funding from either private donations or external grants to provide scholarships for students, start programs, or implement improvements to offerings,” Cox said. “Colleges have differing levels of staffing and overall capacity to obtain resources through philanthropy, external grants, business and industry partners.”

For many colleges like Halifax Community College, Elliott said they don’t have a grant writing office, much less a grant writer.

“So oftentimes, institutions like ours are just not able to be in the game,” she said.

White raised similar challenges at Haywood Community College.

Even when colleges can find the capacity and resources to seek grants, they also need capacity to implement those grants. That means having the staffing capacity to seek, write, and submit grants, but also to meet grant requirements and reporting deadlines.

“We’ve been successful in getting large grants, but at some point we are maxed out in being able to manage them,” White said. “A lot of grants don’t want to fund a business officer person, for example. But you don’t want to take on more than you can successfully manage.”

In October 2023, the State Board of Community Board approved Dr. Zach Barricklow, formerly at Wilkes Community College, for the new position of associate vice president for strategy and rural innovation. That role will be based remotely in Wilkes and will involve travel to rural communities across the state “and help us engage in a much deeper way with our rural community colleges,” Cox said.

The Board also approved a position for a director of grants — hiring Kelly Klug with a salary of $105,000 at its January meeting. Klug will serve as a resource for grants within the system.

“These two positions are really going to be a game changer for our strategic plan moving forward,” said Board Member Ann Whitford.

Receipts for tuition and fees

Another indication of the financial health of a community college is receipts for tuition and fees.

All 58 community colleges take in student tuition and fees and those are by law deemed state funds. Regulations of the State Board of Community College control which fees are state funds and which are local funds, and how those receipts deemed state funds are deposited.

President Jeff Cox says that colleges deposit student tuition and fees into local bank accounts, and daily those funds are then deposited into a system office account.

In 2023-24, the state budget anticipates $403,685,353 in receipts across all 58 community colleges. That’s 21.5% of the total state budget for community colleges of $1,877,925,960. You can see the sources of receipts in the state’s certified budget for community colleges.

Here are the receipts and fees by college from 2019-20 through 2022-23, from the Office of State Budget and Management (OBSM). As you look at the increases and decreases over time, remember to consider the impact of the pandemic.

The receipts in 2022-23 across the 58 community colleges totaled $294,146,128.

Currently, excess receipts from the 58 community colleges are used to fund the enrollment increase reserve. That has only happened three times in the last 15 years, according to the system office.

A NCCCS working group on the funding model would like for excess tuition receipts to return to the college which generates them, but only in years when the system as a whole generates excess receipts.

Why funding matters

North Carolina community colleges have a $19 billion annual impact on the state’s economy, according to a study paid for in part by the N.C. General Assembly.

The colleges support nearly 320,000 jobs across the state — and generate nearly double the revenue of what they take from taxpayers.

For every $1 students invest to attend a local community college, they gain $4.50 in lifetime earnings, according to the study.

Community colleges provide affordable higher education and workforce training to their communities. In rural communities, community colleges are sometimes the only higher education institution within 30 miles.

EdNC’s CEO Mebane Rash says, “As they continue to offer an open door to all students, our 58 community colleges must also find the resources to excel in all things, including training the early child care workforce, providing early child care, training first responders, supporting the mental health of those at the college and in the community, training the health care workforce, creating opportunities through early colleges providing opportunities for other high school students to experience college, imagining the future of work, providing local leadership, and more.

Community colleges do a lot in our communities.

“We’re a large system but we’re also effective and a nimble system — overall we’ve got a good foundation,” Hunt said. “We’re all unique, in the needs we have and the needs our communities have. I’m just proud of the work that we do across the state.”

But such work requires resources.

Resources like state appropriations, yes, but also through individual budget allocations, county funds, dual enrollment, foundations, grants, and receipts. All of these factors are necessary for a college — and in turn, its students — to really thrive.

“As the president of a smaller, rural college in the eastern part of the state, every one of these areas is essential fiscal support to help us move the needle in helping our students to be successful,” Elliott said. “And in positioning our college to continue to be a vital resource for our community.”

Behind the Story

EdNC published a public version of the data spreadsheet we created to analyze the research identified in this article. When possible, that spreadsheet includes links to the original data sources EdNC used for our reporting. You can find that spreadsheet here.

You can also find EdNC’s list of special budget allocations for individual colleges on EdNC’s website.

You can view EdNC’s press release regarding this report on our website. For more information, contact lead reporter Hannah McClellan.