The John M. Belk Endowment and Durham-based nonprofit MDC have partnered to examine the patterns of economic mobility and educational progress in North Carolina to determine who is being successfully prepared for entry and success in the most economically rewarding sectors of the state’s economy. The report, “North Carolina’s Economic Imperative: Building an Infrastructure of Opportunity,” provides data and analysis on these trends and includes a close look at eight localities across the state. This week, EducationNC will be featuring the profiles of five of those communities.

Pitt County is understood in North Carolina as “Pirate Nation”—a place bursting with pride and enthusiasm for East Carolina University (ECU) and its landmark presence in the county. Declarations of willpower such as “no quarter,” an expression meant to emphasize that a team never surrenders, can be heard ringing in the stands of the ECU Pirates’ sporting events, but perhaps this boldness describes Pitt County even outside the bounds of college athletics. Economic change is underway; it will take persistence and intentional actions to take advantage of growth opportunities and to ensure that growth benefits not just the residents that are already “winning,” but empowers all residents, especially those previously cut off from opportunity.

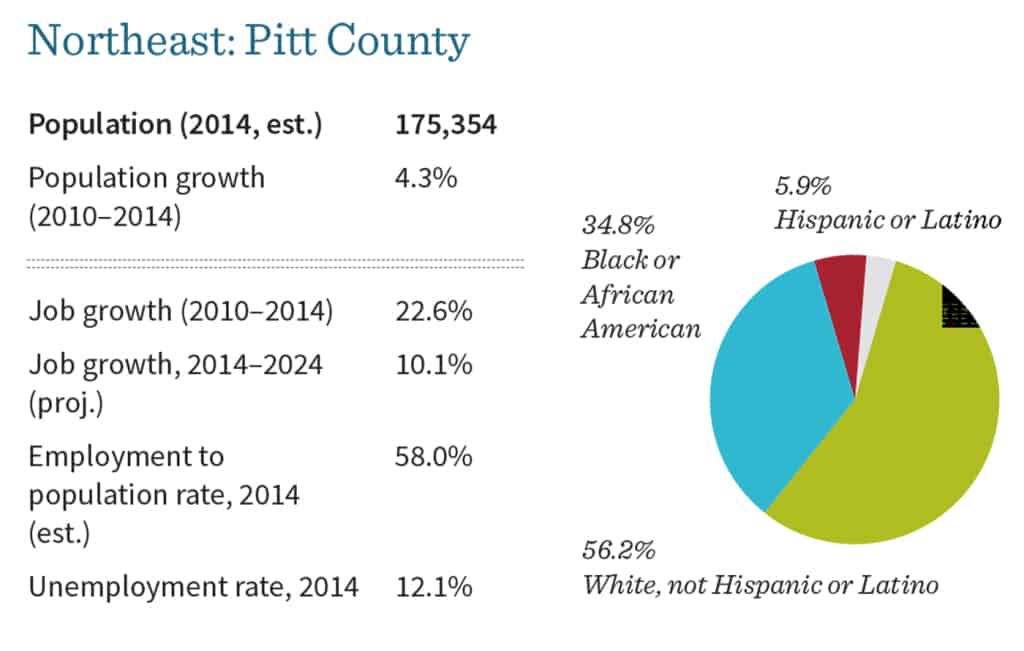

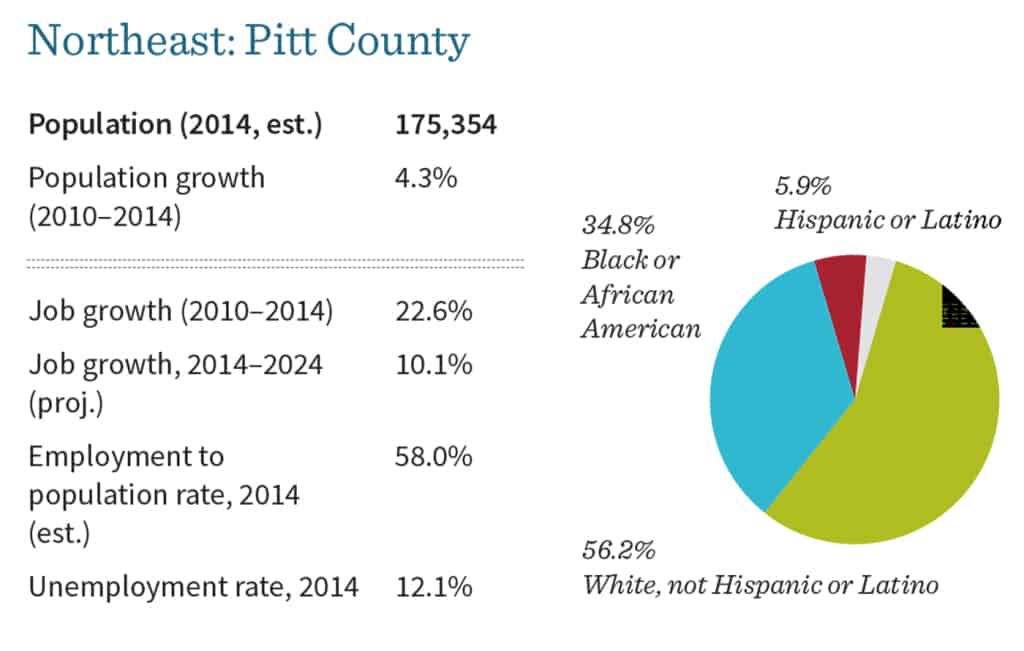

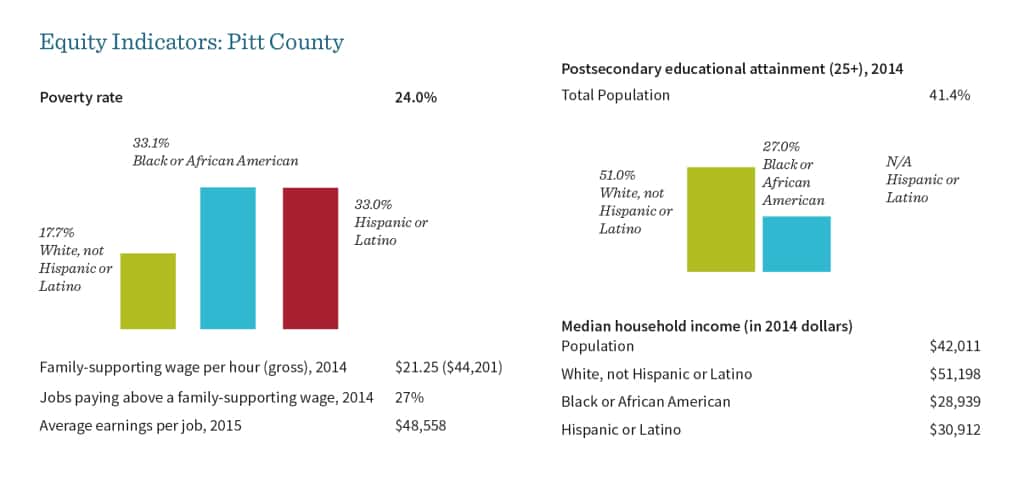

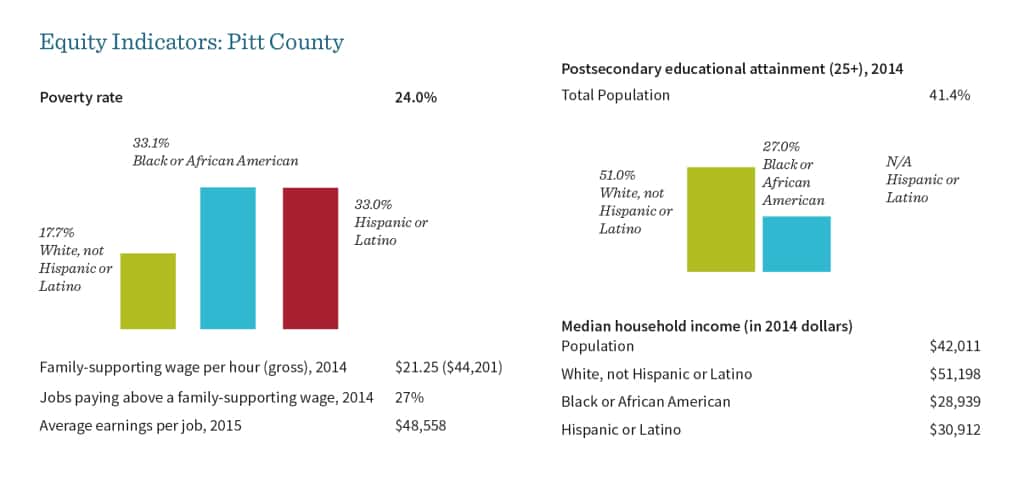

Traditionally known as a rural region focused on agriculture, in 2015 Pitt County had some growing pains. The city of Greenville is becoming an economic hub, with many options for new directions—and many diverse communities in Pitt County at risk of being left behind. Greenville is the tenth largest city in North Carolina, and one of the fastest growing, in the midst of one of the poorest regions of the state. Pitt County has a poverty rate of 24 percent compared with the state rate of 18 percent. African Americans in the region face a poverty rate of 30 percent.

“Med and ed” is the name of the game when it comes to economic vibrancy in Pitt County, with Vidant Medical Center and ECU employing approximately 7,000 and 5,500 people, respectively, of almost 83,000 total workers in the county. It’s difficult to have a conversation about the opportunity available to Pitt County residents without coming back to these two institutions, both located in Greenville—their individual value to the region, as well as their collaborative efforts to help the county thrive. But it hasn’t always been this way. A web of partnerships that include the hospital, economic development, educational institutions, and the larger community of Pitt has been hard-won and strategically designed by leaders intent on putting Pitt County on the map for potential investors.

Manufacturing in the county took a hard hit of 9 percent job loss 1 during the Great Recession, resulting in a wave of displaced workers at Pitt Community College’s (PCC) front doors. But the strong presence of Vidant shielded the county from the worst of the recession; Pitt County economic developers have focused heavily on the growth of the healthcare industry and the attraction of young healthcare professionals to the region. However, there is a growing recognition that too much economic dependence on the hospital system is, in fact, an unsustainable focus for the future of Pitt’s economy, in part because the hospital is both tax-exempt and situated on a large portion of land in the county. Sole economic focus on the medical field also becomes less appealing considering that the Brody of School of Medicine, ECU’s medical school that functions as one of two public medical schools in the state, has faced obstacles in acquiring desired state funds needed to continue serving rural areas to its highest potential.

“The hospital has been an economic pillar of our community for a long time,” says president of the Greenville-Pitt Chamber of Commerce Scott Senatore. “Moving forward, there is certainly an interest in adding other economic pillars in an effort to diversify our economy.”

That’s why economic development leaders in Greenville and Pitt County are looking to advanced manufacturing, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry, to make the county not only a center for the healthcare industry, but also a center of advanced biomedical manufacturing. Patheon—a large, pharmaceutical contract manufacturer—announced its move to Greenville in 2014 as an expansion of the already-significant DSM Pharmaceuticals plant. The company has promised 488 new jobs in Pitt County, in addition to 125 expected from Mayne Pharma—another pharmaceutical contract manufacturer created when an Australian company purchased Metrics.

Bets have been placed and the stakes are high for economic growth in Pitt County. As a result, leaders across Pitt’s sectors are focusing their efforts on whether Pitt County has the capacity to produce the home-grown talent necessary to keep industries invested in the area. Yet in a community that is marked by gaps between urban and rural, white and people of color, and low-income and affluent, a handful of concerned leaders are also asking: As Pitt County builds capacity, how can all residents in such a diverse county have the opportunity to participate in economic growth?

“Pitt County is big enough to have the social problems, but it’s small enough that if it really chooses to come together, I think we can really solve those problems,” says Jim Cieslar, executive director of United Way of Pitt County. “If it can come together.”

“Pitt County is big enough to have the social problems, but it’s small enough that if it really chooses to come together, I think we can really solve those problems. If it can come together.” — Jim Cieslar, executive director, United Way of Pitt County.

Even though Greenville is quickly growing, the cost of living remains low and the area still retains the small-town feel that many residents love. However, leaders in development recognize that the in-between feel of Greenville does not appeal to everyone. For young professionals not quite ready to settle down and raise children, Greenville may seem to offer little in the way of cultural attractions. And for many young adults who grow up in Pitt County with a big-city thirst, a certificate or degree from ECU or PCC may be understood as their ticket to somewhere new.

“Corporations in the region have a really hard time recruiting engineers and keeping them,” Dr. Ron Mitchelson, provost of ECU, says in explaining the decision behind the university’s new School of Engineering. “And about the time you have them trained up the way you want them, they’re on the way out. So homegrown, from our perspective, is superior.”

“Corporations in the region have a really hard time recruiting engineers and keeping them. And about the time you have them trained up the way you want them, they’re on the way out. So homegrown, from our perspective, is superior.” — Dr. Ron Mitchelson, provost, East Carolina University

The challenge of retaining home-grown talent is even starker when considering that more than 24 percent of Pitt’s residents live below the federal poverty line. Even though the presence of Greenville gives the impression that the region is prosperous, there are many underserved areas and populations within the county. For example, the region has a sharper race divide than the state as whole: while Pitt County has a larger African-American population than the state average, African Americans’ median annual household income is 45 percent less than that of the county’s white population. Additionally, Pitt County sees wider stratification between the white and black populations’ educational attainment rates, with the white county average of postsecondary degrees higher than the state average and the black county average lower, resulting in a 26 percent gap in educational attainment between the two groups. The education divide has a rural versus urban component to it, as well; for example, in 2013 nearly 90 percent of adults 25 years or older in Greenville had attained a high school diploma and 37 percent had attained a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared with 75 percent and 13 percent, respectively, in the rural municipality of Ayden, 11 miles south of Greenville.2

Rural communities outside of Greenville fall in PCC’s service area, but the lack of regional public transportation keeps many from entering programs that would connect them with jobs. The N.C. Department of Commerce reported that in 2013, less than 1 percent of Pitt County residents used public transportation in their commute to work. This statistic brings to light what leaders across sectors in Pitt describe as a sorely limited public transportation system, both within the city of Greenville and between Greenville and surrounding rural towns, where 25 percent of the county population resides. The pairing of above-average poverty rates and geographic isolation from work and education makes adequate public transportation a particularly critical piece of Pitt’s infrastructure of opportunity. And Ernis Lee, outreach coordinator for PCC, understands that there are circumstances outside of the classroom, such as childcare, food scarcity, and family health that keep students from giving academics their undivided attention once they leave the classroom: “Regardless of the work that we do, there’s a lot of social issues going on for students that we can’t do anything about.”

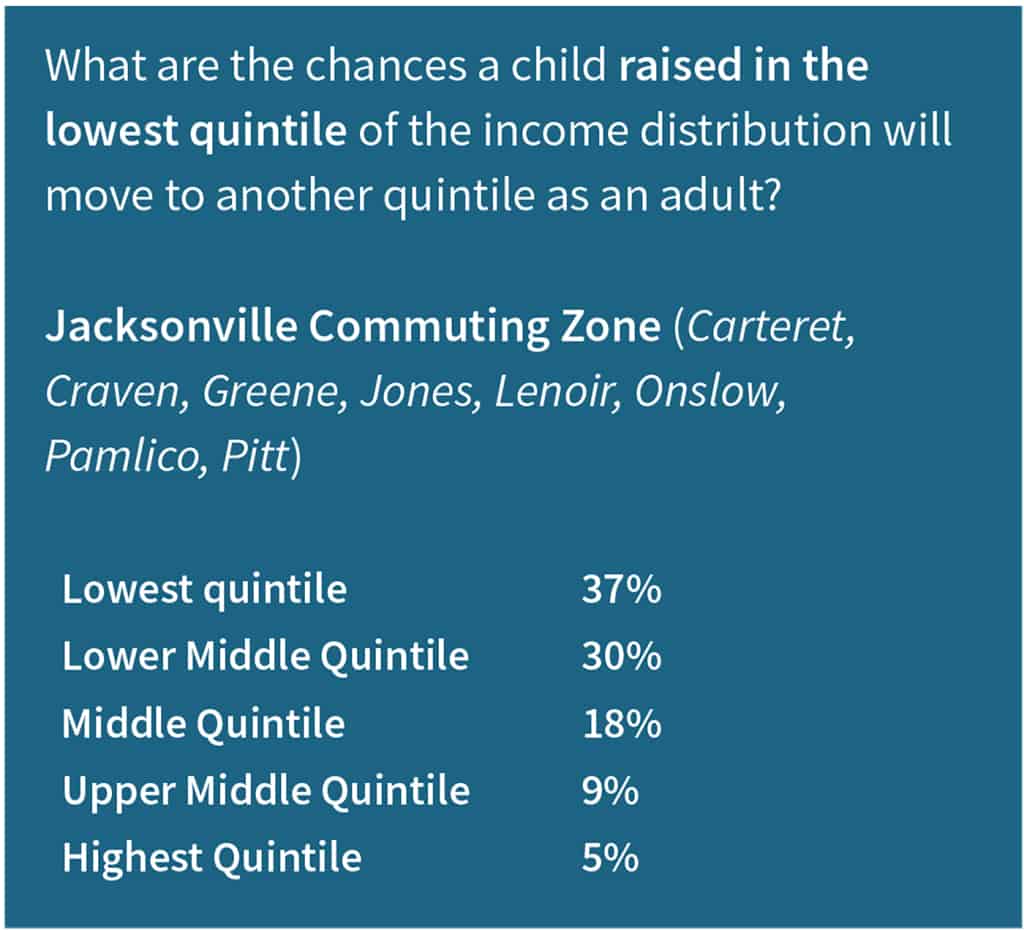

There’s an undeniable cycle of poverty in Pitt County—a cycle that situates children and adults in less ready positions to take advantage of opportunity. Some community leaders, such as Wanda Yuhas, the director of Pitt County’s Economic Development Commission, worry that while Greenville grows, a division between two populations will be exacerbated: a Pitt County that is thriving and a Pitt County that is struggling. “People tell me, ‘There will always be some version of that kind of division. We will never have everyone working at Patheon,’” Yuhas says. “And I recognize that, but I also think that we can have meaningful employment for most people.”

Community leaders in education and economic development are assessing the situation and recognizing a vital connection between curriculum and industry, for both meeting the needs of employers invested in the region and keeping students engaged in what Pitt County has to offer. As Pitt expands its advanced manufacturing sector, this means also expanding educational programs not traditionally offered at a four-year school, resulting in increased attention on Pitt Community College. “If there’s any place that benefits from their community college, we do,” says Dr. Dennis Massey, president of PCC, speaking to the needs of both employers and the population.

“If there’s any place that benefits from their community college, we do.” — Dr. Dennis Massey, president, Pitt Community College

Educational institutions and economic development leaders are working together to address needs of both the working population and invested industries. “If we’re not teaching what industry needs, we’re wasting our time,” says Mark Faithful, dean of construction and industrial technology at PCC. That’s why representatives from ECU, the community college, economic development, and the Chamber of Commerce are at the table with employers in the area, making sure that development of curriculum is an iterative process that doesn’t leave students hanging when they reach the end of their degree or certificate. For example, when Patheon was deciding to come to Pitt County, industry leaders met with PCC representatives, who assured that the college was well-positioned to provide the company with a talent pipeline.

“If we’re not teaching what industry needs, we’re wasting our time.” — Mark Faithful, dean of construction and industrial technology, Pitt Community College

Leaders in Pitt County recognize that living up to this promise and bolstering the robust education-to-career continuum will require a good bit of collaboration between industry and the county’s three educational institutions. These cross-sector conversations have informed ECU and PCC’s decision to partner, with the support of the Golden LEAF Foundation, to create the Biopharmaceutical Workforce Development and Manufacturing Center of Excellence. The center has been proposed as a site of collaboration between education and industry to ensure that residents looking to enter advanced manufacturing in health sciences are trained in the specific skills needed to engage with the demands of Pitt County’s growing economy as companies look to hire locally. While design of the center is still underway, leaders at ECU and PCC hope that once the center is available to the community, it will function to attract both workers and industries to job opportunities in Pitt County.

PCC, ECU, and the Pitt County Schools (PCS) system recognize that attracting students to STEM fields starts early, in order to meet the advanced manufacturing needs of the growing industry in the region. In order to do so, the three institutions are working with business in the area to expose middle and high school students to STEM courses that make tangible links between curriculum and job opportunities in Pitt County. For example, the NCEast Alliance, a regional economic development organization, has seen the growing need in Pitt County for the technical and workplace skills required to enter a career in advanced manufacturing. With the support of the Golden LEAF Foundation and Duke Energy Foundation, the Alliance has created STEM labs in middle schools in several counties in the eastern part of the state, including Pitt. Students work in engineering labs that require two partners to accomplish the work, which heightens the pressure on each student to show up and pull their weight. The students work together on hands-on STEM projects that program directors show to local business leaders. Employers then explain to students how their projects relate to their industries’ work. This shows students early-on that their courses are relevant and opportunity is close at hand.

Rather than targeting exclusively college-bound students, this middle-school STEM program is also geared toward increasing opportunities for students who perhaps didn’t see themselves on a college trajectory. “We hope to reach students who are likely to be left behind, and show them that a four-year degree isn’t the only way,” says John Chaffee, president of the NCEast Alliance.

“We hope to reach students who are likely to be left behind, and show them that a four-year degree isn’t the only way.” — John Chaffee, president, NCEast Alliance

At the high school level, however, a program called the Health Sciences Academy provides additional education for students who do intend to pursue a postsecondary education. The academy was formed in 2000 through partnerships between ECU and the Brody School of Medicine, Eastern Area Health Education Center, Greenville-Pitt Chamber of Commerce, Pitt Community College, Pitt County Schools, and Vidant Health.

The program allows students in Pitt County high schools to take at least six courses over the span of four years, starting their first or second year of high school, to introduce them to the range of careers available in health sciences as they go on to seek postsecondary education at a variety of schools, including ECU or PCC. “We’re not just looking for bedside care,” says Lisa Lassiter, the administrator of Vidant Health Careers, commenting on the rationale behind the development of Health Sciences Academy. “We’re looking for lots of different people from different backgrounds and degrees. We strive to expose and groom the students to the many opportunities available.”

The program is available to students who have a 3.0 GPA or higher, have a clean disciplinary record, and are willing to commit to 100 hours of community service over four years, or 25 hours each year. However, Lassiter commented that most students in the program go well above the community service hours requirement in an effort to bolster their résumés for college acceptance and potential scholarships. Of all the academy graduates since 2000, 42 percent are now employed by Vidant, and 80 percent remain in the eastern region of the state, demonstrating the value of the academy in keeping home-grown talent at home.

In this way, Pitt County leaders are making efforts to connect students across course levels with meaningful opportunities, specifically in the life sciences field. “We haven’t really come across a roadblock we couldn’t figure out,” says Dr. Ethan Lenker, Pitt County Schools superintendent, speaking on the collaborative relationship between the university, the community college, and the school system. “It’s all about open-mindedness and doing what we can to create opportunities for the kids.”

“We haven’t really come across a roadblock we couldn’t figure out. It’s all about open-mindedness and doing what we can to create opportunities for the kids.” — Dr. Ethan Lenker, superintendent, Pitt County Schools

Nevertheless, there is a growing recognition among community leaders that if the region is going to thrive, services and programs that intervene even as early as middle school won’t cut it—the root causes that result in students becoming disengaged have to be addressed at an even younger age. “You can’t provide enough services to move the lever,” says Jim Cielsar, executive director of United Way of Pitt County. “You’ve got to really change the conditions in the community in order to move the lever.”

“Moving the lever” is exactly the focus of United Way of Pitt County, picking up on a new strategy for systems change that several United Way entities across the nation have adopted. “The purpose is to be in the face of the community about how well or how poorly we’re doing,” Cieslar says, noting that the strategy has shifted away from funding a wide array of organizations and toward addressing root causes. The root cause where United Way of Pitt County is placing their bet? Early literacy.

And it’s not just the United Way—economic developers and other nonprofits, such as the Martin/Pitt Partnership for Children (MPPC), have been shaken by the fact that 42 percent of Pitt County kindergarteners enter school without the appropriate level of school readiness. It’s an effort that’s building momentum, in part because the United Way and MPPC have communicated that investing in early childhood education isn’t just a good deed—it’s a smart economic investment. That’s why Wanda Yuhas, director of Pitt’s Economic Development Commission, is on the board for MPPC, and other leaders such as Adelcio Lugo from Self-Help, a community development credit union, and Scott Senatore, president of the Chamber of Commerce, are pointing to early childhood efforts as beacons of hope for increasing opportunity in Pitt County. Investing in early literacy is part of an emerging, cradle-to-career continuum strategy that Pitt County leaders will continue to develop in an effort to build home-grown talent momentum from an even earlier starting point.

“You can’t provide enough services to move the lever. You’ve got to really change the conditions in the community in order to move the lever.” — Jim Cielsar, executive director, United Way of Pitt County

Leaders in Pitt County are excited by the prospect of advanced manufacturing industries looking to the region for development, as well as the collaboration between business, government, and education to provide and maintain the home-grown talent to feed that industry. But the climb on many challenges remains steep. At the same time as Pitt Community College becomes a more important center for opportunity and education to connect residents with booming industry, obstacles keep certain populations in Pitt County from accessing programs with as much ease as others. Strategies are in the making to bridge these gaps, including a PCC center in Farmville that will start hosting classes in 2016 and efforts to bring successful job training programs to West Greenville, where poverty is most concentrated. Leaders in education and economic development point to STRIVE, a program offered by nonprofit L.I.F.E. of N.C., Inc., that provides disconnected adults with job application skills, as an intervening force for residents who struggle to attain upward economic mobility in Pitt County. But community-based organizations that support residents from the beginning, rather than providing supports to get them back on their feet after they’ve already fallen on hard times, are lacking.

Because poverty in Pitt County is cyclical, programs that support families and residents more holistically would further address the disparities in education and career opportunities present in the region. For example, programs such as the Health Sciences Academy are valuable assets to producing local talent and connecting a cohort of students with booming industries in the eastern part of the state. But how can students who experience barriers to reliable transportation, have after-school employment, or have care-taking responsibilities, participate fully, or at all, in programs that require students to spend additional time outside the classroom? In this way, though Pitt County intentionally has programs in place to provide pathways to opportunity, certain circumstances place residents in a less favorable position to access these pathways.

As advanced manufacturing and life science industries grow in the region, community leaders are enthusiastic about the opportunity at hand, while also apprehensive about keeping up with the needs of employers. There’s an understanding that staying in collaboration with industry demands and having an accessible curriculum are essential, and the challenge of making sure all the right players are at the table will remain critical to Pitt County’s efforts.

“I really think that institutions have a better idea of what’s going on now, and they’re doing a better job of getting individuals in place who know how to reach this generation,” says Denisha Harris, with the Minority and Women Business Enterprise Program of Greenville. “And I see the changes happening and I see the growth in our communities, and I’m really proud of that as a native. But it takes time. People don’t move just because you say ‘go.’”

It’s a tough balancing act: celebrating the growth and potential in Pitt County while recognizing that many residents are not well-positioned to access the opportunity being created. “How do we as a community say, ‘We’re doing all this great stuff, but we’ve still got an issue,’” Yuhas says. “How do we innovate in [intergenerational poverty]? How do we innovate to break that cycle?”

“And I see the changes happening and I see the growth in our communities, and I’m really proud of that as a native. But it takes time. People don’t move just because you say ‘go.’” — Denisha Harris, Minority and Women Business Enterprise Program of Greenville

NORTH CAROLINA’S ECONOMIC IMPERATIVE: BUILDING AN INFRASTRUCTURE OF OPPORTUNITY

Part 1–Introduction

Part 2–Cultivating aspirations: Vance, Granville, Franklin, and Warren Counties

Part 3–Partners at the speed of trust: Guilford County

Part 4–Recovery through collaboration: Wilkes County

Part 5–Landscape defines opportunity: Western North Carolina