A confession: I put off this assignment for several days. How in the world do I choose a favorite teacher? There were so many extraordinary educators in my school career. Perhaps I should narrow my focus to just those who taught me about words since that is my daily work currency.

But that only shrinks the pool slightly.

I could pick Ms. Morris, my high school English teacher who taught me the power of beautiful writing.

I could choose Ms. Franklin, my 8th grade English teacher who gave me a deep appreciation for eliminating linking verbs (an appreciation likely despised by those I presently edit).

I could write about Ms. Riddle, another high school English teacher, and her insistence on “specific supporting detail.” She would be pleased to know that I often scribble that very phrase on papers I now edit.

Or I could share stories about Ms. Gardner and how her statement, “Life is too short to read books you don’t like,” has stuck with me throughout the years.

But perhaps no one was more instrumental in my education than the woman who first taught me about words: my kindergarten teacher, Ada Gaskill. She later became Mrs. Thomas, but to me, she was always Ms. Gaskill.

To understand how her influence shaped my love of language, one must understand Ms. Gaskill.

More than 30 years later, my dad still recounts the story of the first parents’ night in Ms. Gaskill’s class. The parents milled about, chatting with one another, until Ms. Gaskill called the evening to order and commanded them to take a seat on the carpet. The parents chuckled and continued standing, assuming she must be joking. She was not. She waited, looking sternly around the room as the parents sheepishly took their seats, cross-legged on the worn carpet.

Ms. Gaskill was that enviable combination of strict and kind. Long before childhood nutrition was in the headlines, Ms. Gaskill bribed us with stickers if we would choose plain milk over chocolate milk. To this day, I cannot drink chocolate milk.

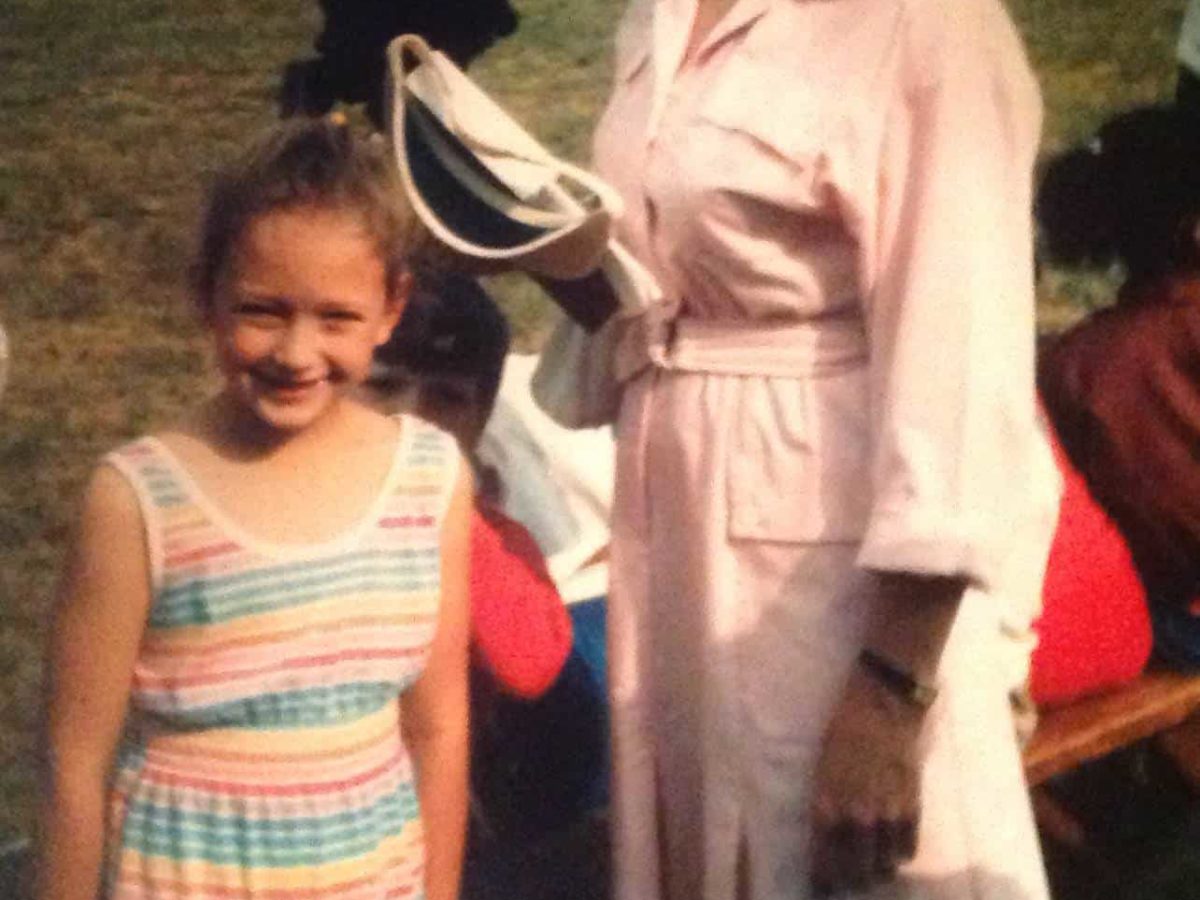

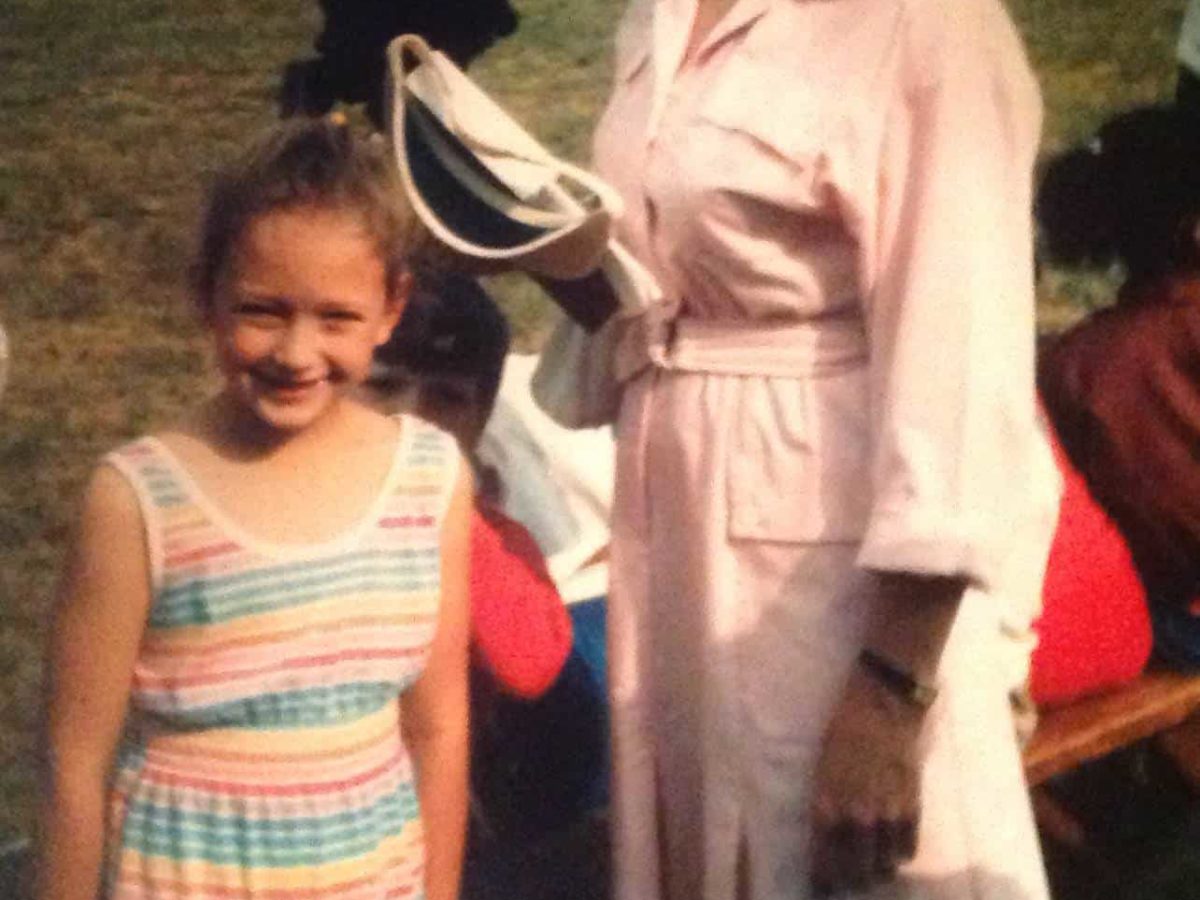

She understood the idea of addressing the needs of the whole child, well before social science research examined the issue. She awarded one student a week the “Good Citizen Award.” I still feel a sense of pride when I see the photograph of tiny pig-tailed me, in a sundress, proudly displaying my “Good Citizen” badge.

Ms. Gaskill possessed strong-willed determination that we would be exceptional little human beings. She demanded a lot from a room of rowdy five-year-olds, but to our minds and hearts, her demands always seemed achievable. She instilled a sense of confidence in us that made her tough standards attainable.

Ms. Gaskill believed in an old-school approach to almost everything, including reading. She taught phonics way before anyone became hooked on it. Words came together slowly from isolated letters; then those words joined to make sentences, sounded out syllable-by-syllable.

A big chart on the board noted our progress in a race to be the student who completed the most books. Ms. Gaskill’s strict but patient pedagogy, in combination with the incomparable Blue Bug adventure book series, opened an entire world to me.

I moved on to first grade with a deep love of books. The ability to travel anywhere just by turning a page kept me up way past my bedtime, often reading beneath the covers with a flashlight.

And crafting words on a page, now my career, is also my passion. I am in constant wonder of the ability of the written language to persuade and transform, to inspire and infuriate, to evoke emotion and drive decisions.

Words drive our world.

I am so grateful to Ms. Gaskill for giving me the gift of reading and writing. And to the many educators who shaped and nurtured my love of words, thank you.