Share this story

- How important is exposure to the arts at a young age? Anthony Kelley is a professor of music at @DukeU and currently the @ncsymphony's composer-in-residence. See his journey here and learn about his newest work, "Spirituals of Liberation."

- This North Carolina composer started on a toy piano. Find out how his journey led him to being the @ncsymphony's composer-in-residence.

One of Dr. Anthony Kelley’s older brothers got a toy organ for Christmas. Put aside for two years, it was apparent Kelley’s siblings weren’t interested in playing with the instrument. He picked up the book that accompanied the toy and started trying to figure it out on his own.

He didn’t quite understand how to make music then, but his determination was something his parents noticed. Maybe it could be worth exploring, they thought.

Kelley grew up in Henderson, North Carolina with two elementary school teachers as parents. His first piano teacher was Mrs. White, who lived in the neighborhood and played at a local church.

His parents encouraged his talent, but weren’t going to buy a piano for their young son just yet. Kelley needed a place to practice outside of his piano lessons.

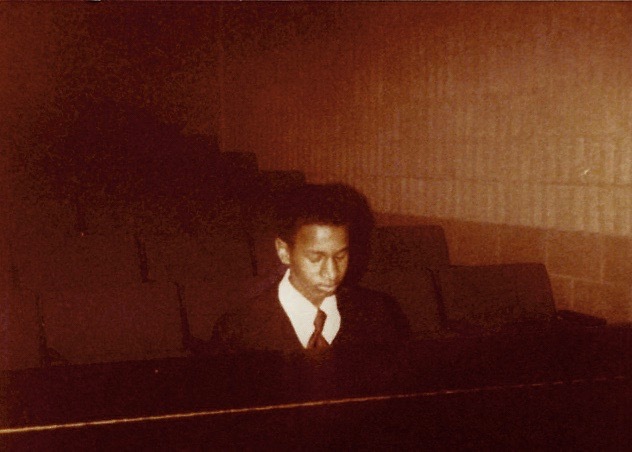

As a sixth grader, Kelley reached out to the custodian at the elementary school behind his house where his mom taught to see if they could work something out. While the school custodian finished his after-school cleaning routine, Kelley used that time to practice piano.

This went on for a year and half, until his parents saw that music wasn’t going to be a passing extracurricular and got a piano for the house.

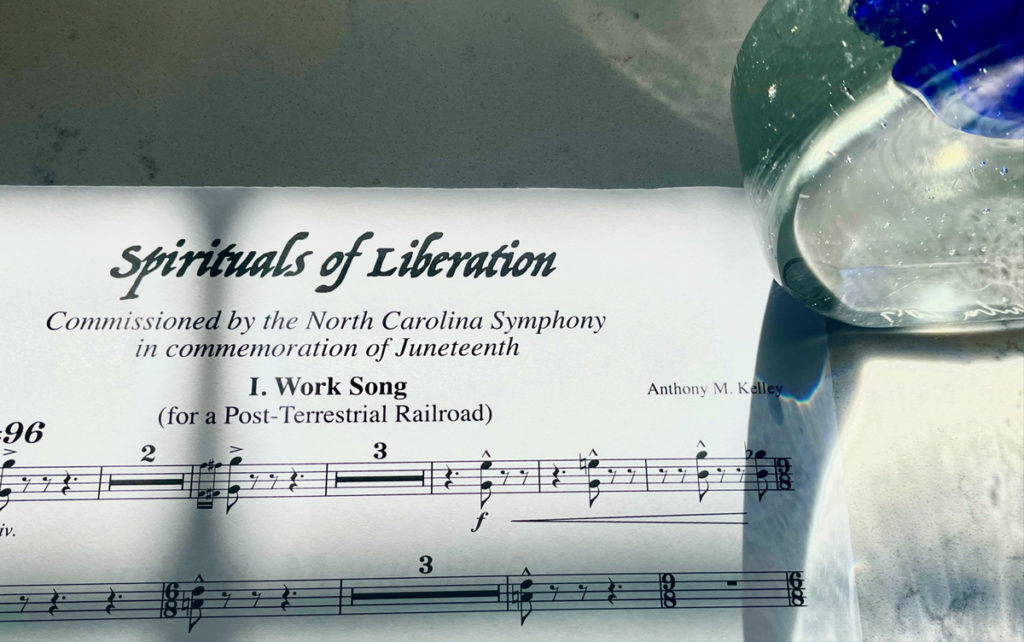

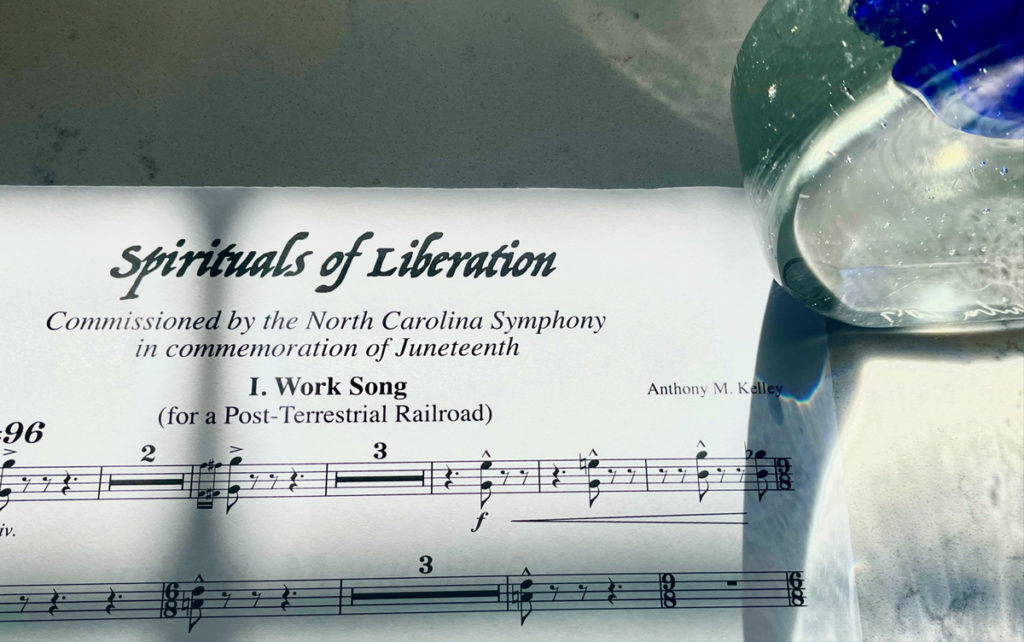

These were the beginnings of a life in music for Anthony Kelley. In what he describes as “a full circle moment in the most gratifying way imaginable,” Kelley is now the North Carolina Symphony’s Composer-in-Residence. On June 18, in commemoration of Juneteenth, his new original composition entitled “Spirituals of Liberation” will be performed at the N.C. Symphony’s Summerfest: Juneteenth Freedom Celebration.

Musical moments of influence

Growing up, Kelley’s musical curiosity wasn’t contained to the piano. At Henderson Junior High School, he picked up the tuba and trombone.

His band director took the class to see the high school band perform an arrangement from one of the movements from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7.

“That turned everything around for me, and I got locked into music from that moment on.”

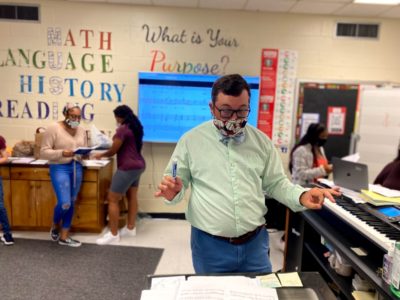

Dr. Anthony Kelley, composer-in-residence and associate professor of the practice of music at Duke University

Kelley had a good friend who played in the band with him in junior high. They would challenge each constantly, playing a game to see which of the two could find more obscure classical music in the library. This friend’s aunt saw their interest and approached Kelley’s parents to offer to take them to Raleigh for a N.C. Symphony performance. The guest solo artist for that show happened to be jazz pianist Billy Taylor.

This was Kelley’s first experience with an orchestra, and having Taylor there speaking one dialogue with both black jazz language and classical language forever influenced Kelley.

“I never separate them. Everything I’ve ever written has those dialogues in it. That moment contributes to my style,” Kelley said. He still has the ticket from that performance.

In 10th grade, he left Henderson to attend Choate Rosemary Hall, a private boarding school. His music theory educator, Ralph Valentine, redirected him into composition at the school. This class helped him understand how to develop harmony and gave context to the history and culture of writing music.

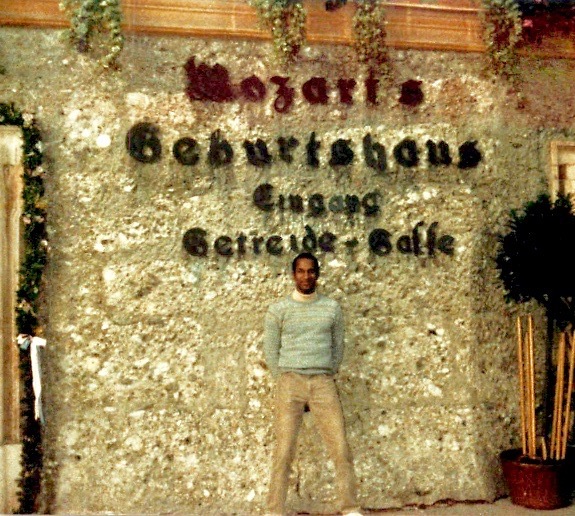

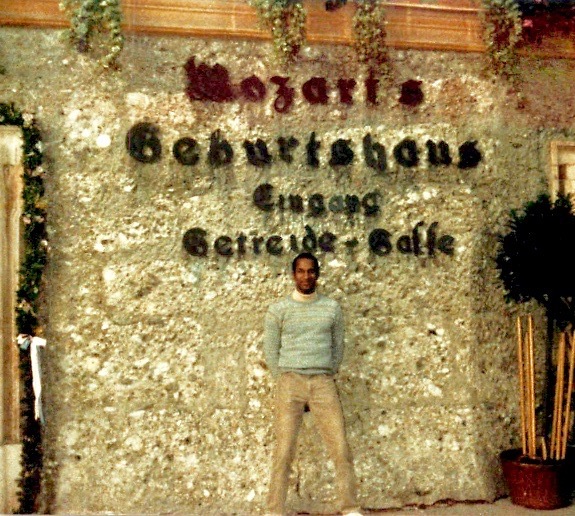

After boarding school, he returned to North Carolina to attend Duke University. It was in his second year where he toured Europe with the wind symphony that his band director made sure they visited the landmarks of great composers. He saw where Mozart lived and where other great composers wrote their first symphonies. Those trips kept the idea of writing music at the forefront of his mind.

He became a composition student of Robert Ward for the remainder of his undergraduate degree. After continuing on to get his masters, he heard the work of Olly Wilson, a Black composer who was based out of the University of California-Berkeley. Kelley was so overwhelmed by the piece “Sometimes” that he wrote a letter to Wilson the next week saying, “whatever you do, is what I want to do more of.”

Kelley received a full ride to University of California-Berkeley to get his PhD and studied with Wilson. Kelley said Wilson is a specialist at understanding how West African music connects to African American music. All of these experiences and more led him back to Duke, where he has been working since 2000.

“Spirituals of Liberation”

To Kelley, spirituals were created out of the necessity of self-expression. They originated as a way for enslaved people to connect to the beyond, whatever the beyond meant for them. It was a way to express hopes, fears and aspirations. “I’m creating brand new spirituals, based on what I know are features of the old spirituals,” Kelley said.

The composition is broken up into three movements. It “covers the journey from the oppression of enslavement through the ecstasy and triumph of liberation, and emancipation,” says Kelley. He wanted it to encompass the total human experience of enslaved people, not just that of enslavement.

The first movement is called “Work Song (for a Post-Terrestrial Railroad),” and Kelley describes it as a little tip of the hat to the work of Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad. In the piece, the audience will hear sounds that mimic that of building a railroad, interlaced with intricate melodies that represent the psychological labor of being enslaved.

“Elegy (for the New Blues People)” is the second movement, and for this piece Kelley was inspired by Imamu Amiri Baraka’s book “Blues People,” which takes into consideration the experiences of second generation slaves and beyond; those who were born in America and don’t think of Africa as their home. These ‘blues people’ are the ones who started to create music that’s not purely of African origin, but a hybrid of their influences.

The third and final movement of Kelley’s composition is entitled “Never Forget.” He describes it as the achievement of actual liberation, and it has references to the work’s other movements.

After the Summerfest on June 18, the N.C. Symphony will continue to perform the piece in a concert series traveling to Chapel Hill, New Bern, and Tarboro. This article will be updated with Kelley’s piece after Juneteenth.