This is Part Five of our series on learning differences. In Part One, EdNC reporter Rupen Fofaria shared his learning differences story. In Part Two, we explored the meaning of the term learning differences. In Part Three, we looked at students with learning differences and what their journeys and successes look like. In Part Four, we spoke with teachers and those working on professional development to supplement educator understanding of learning difference.

Katherine Kelly’s daughter, like her, is diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). But unlike many in her shoes, Kelly’s daughter does not shy away from her learning difference.

“She’s always owned it,” said Kelly, the marketing and communications manager at Eye to Eye National. “She always goes in and just says, ‘I have ADHD, so here are the things that you’re going to notice from me and here’s where I need your help.’”

Bold. Respectful. Intentional. It’s exactly how advocates encourage children with learning differences to behave and how parents are advised to empower their children. Kelly’s daughter stands apart from her friends in that way.

“She has friends who have dyslexia, she has friends who have dysgraphia, she has friends who are on the autism spectrum,” Kelly said. “They would never say that to a teacher. They would never even say that to a classmate because they’ve experienced people saying, ‘You’re just lazy,’ or, ‘Oh, even smart kids say that just to get extra time on tests.’”

For a parent whose child has a learning difference, navigating the journey can be difficult — and the desire to encourage your child to own their difference, like Kelly’s daughter, can be tempered by the fear of stigma, such as laziness or cheating. Advocates say that parents should work on their own acceptance around the issue, increase their understanding of the science behind learning differences, and engage in communities that can lend an ear and offer guidance.

“There’s a lot of fear,” said Teresita Hurtado, learning specialist at the Cannon School in Concord and a mother of children with learning differences. “They’re not going to make it, they won’t go to college — what are they going to do? They’re going to live in my basement for the rest of their life. I mean, there’s some genuine fear there. As a mom of seven kids, and two of them have learning differences, I mean, I felt it too, you know. But it’s okay. It’s a process.”

The following charts are the results of EdNC’s Reach NC Voices survey of parents who have a child with a learning difference.

Parents who have been there, and educators who work with students that have learning differences, say that navigating the journey begins with a parent’s own acceptance and understanding. They say that, as hard as the road is for the child with the learning difference, the parent faces a similar challenge — but need to overcome their own shame and guilt to focus on helping their child.

“I still face my own embarrassment, to be honest, and my own stigma talking about my daughter’s limitations when it comes to her ups and downs and doing her assignments for her classes and things like that,” Kelly said. “It’s something that I always have to contend with as a parent and be her advocate and not let it come out because it’s a process of learning for me as well.”

For parents, the temptation may be to protect their child and hide their limitation. Unlike a physical disability which could be difficult or impossible to hide, such as needing to use a wheel chair, learning differences are hidden away in the child’s brain — making it possible to keep secret.

And in an effort to shield their child from teasing or even discrimination, some parents will advise their kids not to say anything.

“One of the things that every parent does — I now understand this in a whole new way as a parent — is you have a kid and suddenly half your job feels like protecting your child from the nefarious things of this world,” Eye to Eye founder David Flink said. “You want to do your job to make sure your kid looks both ways before crossing the street and not to walk into a store with a stranger. So in that spirit of protecting your kids, is you want them to protect this secret. And that is really a disservice to the kid. I think that inviting kids to tell their stories is powerful.

And what we learn is that the minute kids are able to understand that these words don’t mean anything bad and can be positive, they help you find community and they help you find your way.”

For the child, community begins at home. Parents are in best position to begin a child’s education around his or her learning difference. At the Friday Institute for Educational Innovation, the learning differences team created a parent’s handbook designed to equip parents to do just that.

The handbook covers topics such as attention, memory, and organization issues. It shares information and strategies such as:

- One of the reasons it’s hard to learn when you’re not paying close attention is that our brain cannot turn information into memory when we are not paying attention;

- Help your child come up with a system for flagging important information, tasks, or things they have questions about using symbols and color coding that can be used consistently across school and home life;

- Before your child starts an assignment or task at home, ask them to talk about what they are thinking or how they plan to tackle the task; and

- Sometimes the struggle lies in just getting started. Tell your child to take five minutes to begin the paper or assignment and then give them a quick break or reward for doing it. Next time, try a ten-minute chunk of time, continuing to increase the duration each time.

There is abundant research and information available now about learning differences from organizations like Eye to Eye and the National Center for Learning Disabilities. Becoming educated and gaining proficiency with strategies for learning differences is an important first step. It’s also important to join communities in person or online, such as at understood.org, where parents can find help with awareness, vent frustrations and fears, and find motivation to show up for their children in effective ways.

“From then on it’s been a process for me of figuring out that it wasn’t something that I did or it wasn’t something in my parenting style that was making this happen,” Kelly said. “That it’s seriously the way her brain was wired. It’s honestly what she’s born with and that she’s actually a gifted child. And that makes it easier to relate to other parents in discussing it because they all have the same concerns.”

Kelly reminds parents that while they may suffer from fear and shame, children are experiencing the same emotions and it can have a critical impact on self-esteem.

“Owning your learning style — that’s not a new idea. We just hadn’t scaled that idea yet, frankly because of the shame stigma more than anything else. The most important thing I’ve learned in watching the history of the disability rights movement [is that] the number one predictor for student success with a learning disability is self-esteem. That is the number one predictor,” said Kelly. “And the reason why that’s the case, NCLD published a study that validated this maybe a year or two ago, is that self-esteem is connected with and co-related with self-identity. And so if you have high enough self-esteem, and there’s lots of ways to do that and Eye-to-Eye is one, then you’re able to say ‘Oh, I learn this way and I need this.’ The ‘I need this’ piece is the self-esteem.”

Parents who responded to EdNC’s Reach NC Voices survey about their experiences with learning differences children submitted numerous comments about the state of the education system, teacher preparation, and lack of understanding around learning differences at a local level. And while these issues should be addressed, Flink says it’s important to focus on the things that can be changed in the present — like self-esteem.

“Understanding that young people that have high self-esteem and have a high self-identity and grit and resiliency and self-determination — positive identity-formation of their learning disability — that we can do today,” he said. “We can effectively change culture without massive curriculum redesign.”

One way to do this is to disengage from arguments and battles and instead focus on the underlying issues and reaching for common ground. One area of common ground is language.

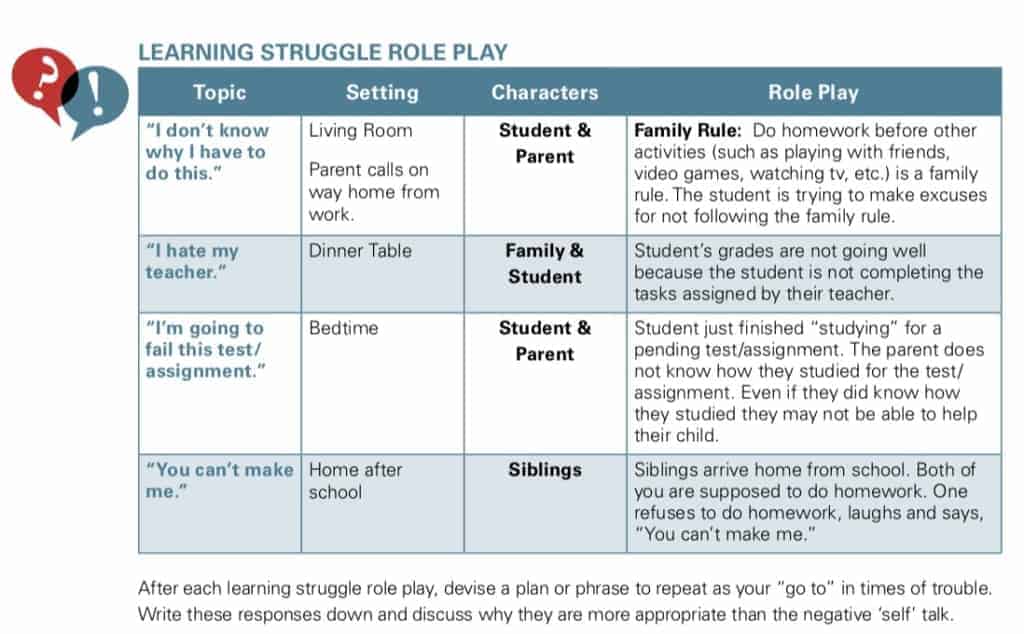

“We provide a lot of discussion questions, with the goal of having non-threatening questions,” said Mary Ann Wolf, director of the Professional Learning and Leading Collaborative at the Friday Institute. “Because I think there are a few parents out there who are having these conversations already — but it’s just, do you have them effectively? Or am I just frustrated with the child … So it’s having the words to talk about it in a productive way, not in a ‘why did you wait until the last night to do your project?’ way.”

Waiting to have these conversations can make engaging children more difficult. Starting in elementary school, when challenges are more manageable and children are more prone to entertain parental inquiry, can help to establish them as habits before the turning point where kids are no longer able to hide their differences and less likely to be completely open with parents.

“That turning point happens in middle school,” Kelly said. “Middle school is the hardest point for just every teen, honestly. You’re already in an awkward phase of your life, you’re figuring out who you are and where you fit in. And to have that added label of having dyslexia or having ADHD or a learning difference tied to you makes it that much harder as a student in middle school growing up.”

For Hurtado, empathy for the kids and the parents is necessary. Parents, she says, might sometimes just need that reminder that their child is not in trouble or incapable. A reminder that everything can work out, and that there are many resources out there to help.

“These things are not mutually exclusive,” she said. “Our kids are very, very smart. And they learn differently. So that’s kind of been a huge mind shift for all of us — but it especially can be challenging with parents, because it’s a frightening place.”

Hurtado carries reminders of student successes in her office, and she shows concerned parents pictures of other children who have learning differences and experienced success, such as going to college.

“And those are the successes that mean something, that get a parent to hang in there when it’s hard — because it’s hard,” she said. “It is hard to be a parent, period. And it is hard to be a parent of an adolescent or a teenager. But it is really hard to be a parent of an adolescent who has a learning difference. Because, you know, homework, nights, rituals, habits, things that maybe other parents might take for granted are not happening to that house without a real battle. So mostly, I try to have empathy.”