A former car door manufacturing building in Rocky Mount hides a secret — one that is accelerating children’s reading levels by 14 months in the span of eight weeks.

That building now houses Rocky Mount Peacemakers, a Christian community development organization, and one of the programs it runs is the Children’s Defense Fund’s Freedom School.

Over two months this summer, 120 kids came to the Freedom School from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. every day for intensive reading and STEM instruction. But while that may sound an awful lot like school, it’s an altogether stranger creature.

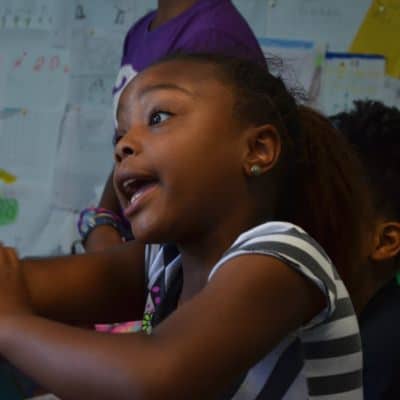

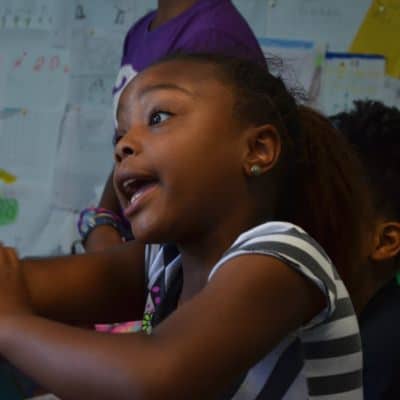

“I love the fact that these scholars can come here and be superstars,” said Shauna Jones, a Halifax high school teacher who spent this summer teaching at the Freedom School in Rocky Mount. “Everyone is loved equally, and they’re celebrated and they’re highlighted daily.”

Clay Grubb is a real estate developer and philanthropist in Charlotte, who doesn’t get too excited about much. But he thinks the Freedom Schools are amazing. Amazing enough that he now serves on the board of directors for Children’s Defense Fund. He has videos on his i-Phone from his visit to the Rocky Mount Freedom School, which he willingly shows to friends and colleagues. “I love the focus on building character in these young scholars,” he says.

Welcome

As students trickle in to the Freedom School, teachers will stand outside to meet them. But this is no simple, “Hi, how are you doing?” Instead, they treat each kid like a celebrity, sometimes greeting them with song, dance, or even excited squeals.

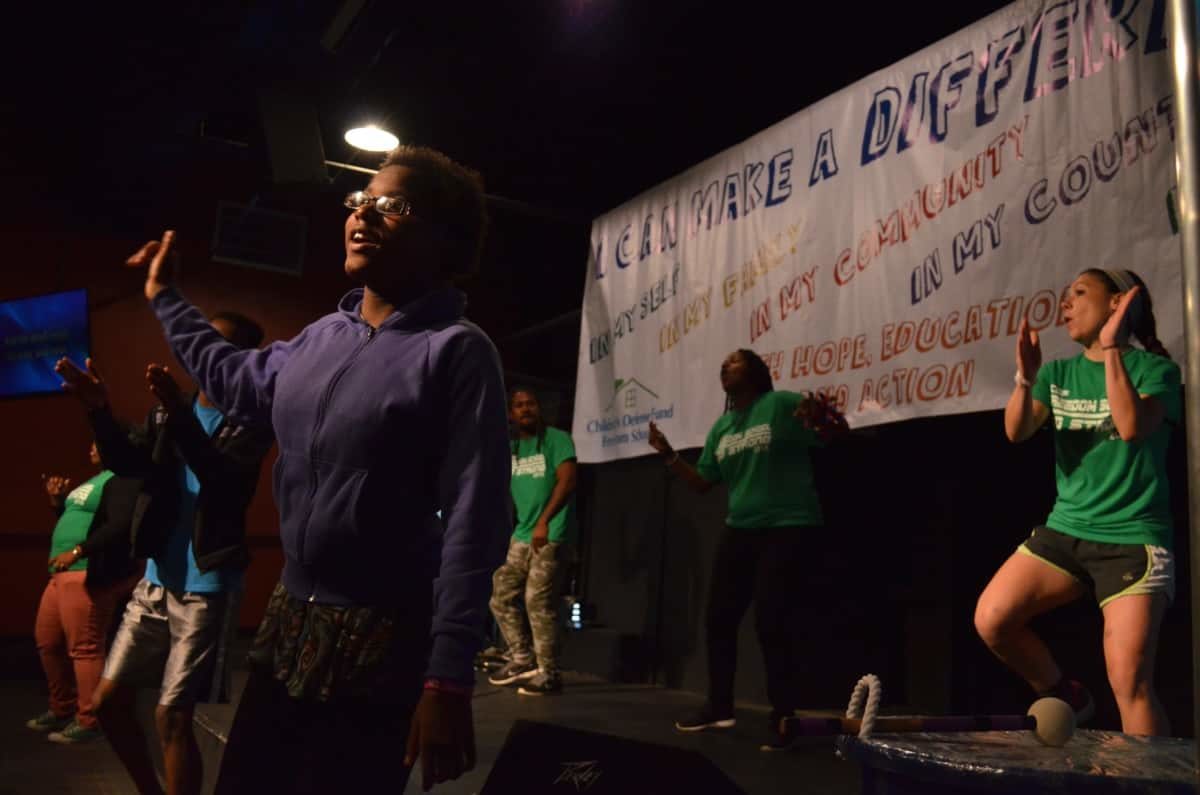

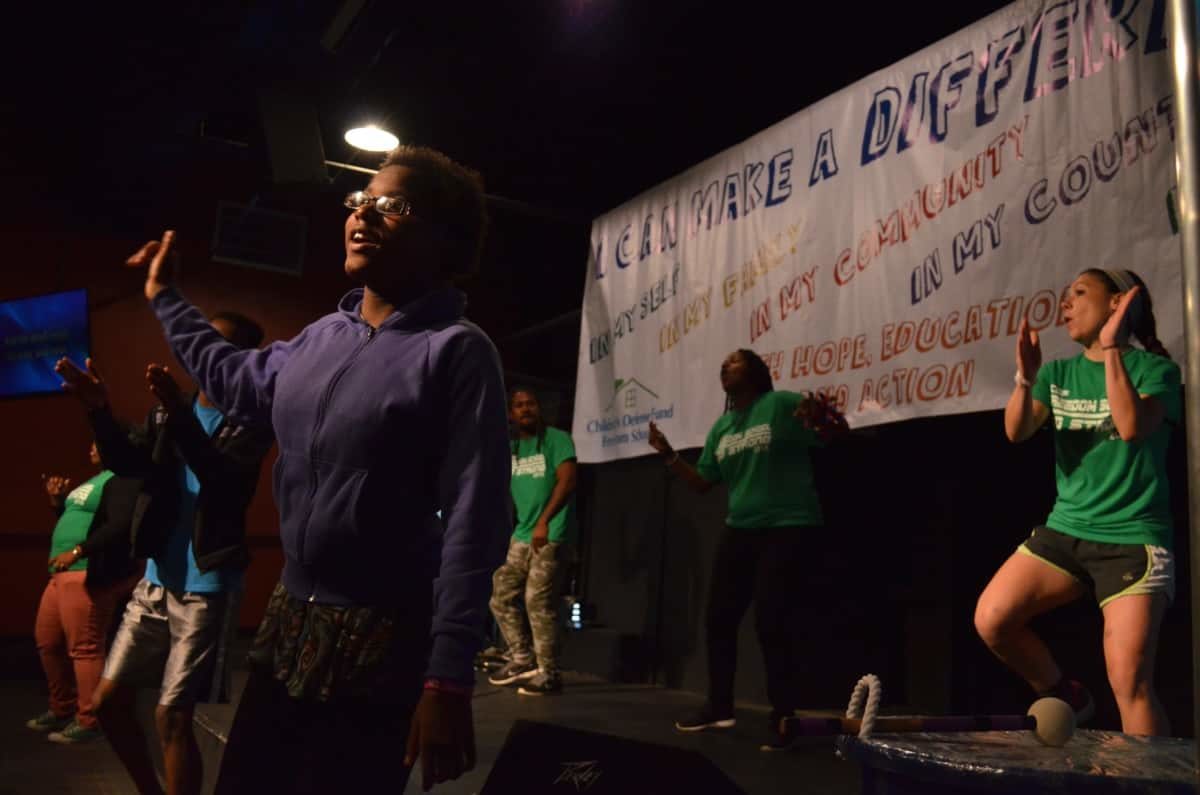

The enthusiasm continues during the morning rally called Harambee. That is a Kiswahili term that means “pull together,” which doesn’t really do justice to what happens at this half-hour spectacle.

A seemingly never-ending parade of songs, dance, chants, and celebration. The teachers and the kids — called scholars at Freedom Schools — moved around the auditorium in fits of excited movement. The day I came, a guest reader from Tarboro — Inez Ribustello who owns and operates the restaurant On the Square — read from a children’s book and was thanked by the kids with a chant, claps, and stomping feet.

“It’s all about coming together, loving each other, creating an atmosphere of positivity and also affirming scholars and celebrating reading,” said Nate Reisinger, a Halifax middle school teacher. This is Reisinger’s third summer working at Freedom Schools.

It really is nearly impossible to describe all this to you. You have to watch the videos to truly understand the energy, engagement, and excitement.

Down to work

Once Harambee is over, it’s time to get down to work. The scholars spend three hours in the morning doing intensive reading work in groups. But, the program is broken up into 10- to 15-minute blocks so that the kids don’t get too bored.

“Everything that we do here, we try to make it really interactive and fast paced,” said Jesse Lewis, executive director of the Rocky Mount Peacemakers.

The lessons are targeted as needed. Lewis said the program has a reading specialist on staff that tests the kids at the start of the summer to see where they need remedial help. The specialist crafts packets for the kids who need a lot of remediation, and volunteers pull those kids out to work with them one-on-one using the packets.

After that, it’s on to lunch, followed by an afternoon activity. In years past, Lewis said they have put on musical productions. This summer they did a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) club. The kids could pick different tracks — things like engineering, computer science, or animal science — and they would stick with that specialty all summer.

By the end of the summer, the kids leave having gained something invaluable.

The past two summers, Lewis said the average reading score for students in his program went up by 11 months. This summer, the scores went up by 14 months.

“We’re really happy with the way the summer has gone,” he said.

But the program is about more than just reading. The curriculum includes “high quality academic enrichment; parent and family involvement; civic engagement and social action; intergenerational leadership development; and nutrition, health and mental health.”

The students

The progress the Freedom School program makes with these children is notable also because of the challenges these students face.

Preference is given to students from the low-income neighborhood surrounding Peacemakers. Students who have at least one parent incarcerated, students who have been referred by court counselors or social workers, and students considered by the school district to be homeless also get preference. Most of the students in the program are African American.

And the Freedom School staff also has to deal with students who, in some cases, pose behavioral challenges.

“We know going in to the summer that we’re going to have some behavioral issues,” Lewis said. “But those are the kids we want.”

The history

The Freedom School in Rocky Mount isn’t unique to North Carolina, though Lewis said it’s the only one east of Interstate-95. He said there are 16 in Charlotte and one in Winston Salem.

The Edgecombe County Public School system is hoping to expand the program into its district. And Clay Grubb would like to see the program expand statewide.

There are Freedom Schools all over the country. It’s a project of the Children’s Defense Fund, and it dates back to the 1960s.

In 1964, two Civil Rights organizations — the Council of Federated Organizations and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee — started the Mississippi Freedom Summer Project.

Part of that project was the Freedom Schools, which offered free summer education to Black students in Mississippi.

The notion of Freedom Schools was relaunched in the 1990s by the Children’s Defense Fund’s Black Community Crusade for Children. The first two of these new Freedom Schools started in 1995 in South Carolina and Missouri.

Individual Freedom Schools pay the national program, and in return receive curriculum, books, and training. Teachers in the Freedom Schools, often college students, participate each year in the Ella Baker Child Policy Training Institute held in Tennessee at the farm where Pulitzer-prize winning writer Alex Haley once lived. There the teachers learn how to implement the curriculum developed for Freedom Schools.

Individual Freedom Schools have to find their own funding. Lewis says he gets his funding from a mixture of grants, some money that comes from the local school district, and a few thousand dollars that comes out of Peacemakers’ general fund. The program has been running at his site since 2012.

In Rocky Mount, the program is free for students except for a $35 registration fee.

It works

Reisinger learned about Freedom Schools from a fellow teacher of his. He started looking around for a site where he could get involved and found the Rocky Mount location. That was three years ago.

“I immediately fell in love with it.” He said. “It’s a really incredible place. And it works.”

Jones also heard about the program from co-workers.

“When they introduced me to it, I was like, I’ve got to be a part of it,” she said.

They both note the positivity they feel in the Freedom School program. And they also like that the program uses culturally-relevant literature as a way of better engaging the students.

“What we’re trying to do is help scholars fall in love with reading by making it relevant to their lives,” Reisinger said.

Lewis also touted the cultural relevancy of the literature as one of the positives of the program.

“I have kids that come up to me all the time and say, ‘Hey this book is just like me,'” he said.

But mostly, the teachers and staff feel like they’re making a difference. Getting the kids interested in reading, increasing their literacy levels, and making them enthusiastic about learning keep teachers like Reisinger coming back year after year.

“It’s the best thing I’ve done in education,” Reisinger said.

Making a difference

Mary Nell McPherson is the executive director of Freedom School Partners in Charlotte. “Summer learning is just tough,” she says. “But Freedom Schools is a really good model.”

“Poor children need care, poor families need care,” McPherson says. She sees Freedom Schools as a community partnership that provides whole child/whole family support.

McPherson says students emerge from the program knowing they can make a difference. The program imparts to each student,

“I can make a difference in myself, my family, my community, my country, my world.”