Share this story

- “Recognizing the impacts of the Federal Indian boarding school system cannot just be a historical reckoning,” Interior Secretary Deb Haaland said. Read about how the Federal Indian boarding school system plays into North Carolina's history.

- On Wednesday, the U.S. Interior Department released Volume I of its Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report. Find out about the history of Federal Indian boarding schools in North Carolina.

The U.S. Department of the Interior released a 106-page investigative report regarding the Federal Indian boarding school initiative on Wednesday. This report is the first step of many the department is taking to address the history of Federal Indian boarding schools in the United States.

The investigation revealed that from 1819 to 1969, the Federal Indian boarding school system consisted of 408 schools across 37 states, including four in North Carolina.

“This report confirms that the United States directly targeted American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children in the pursuit of a policy of cultural assimilation that coincided with Indian territorial dispossession,” Bryan Newland, assistant secretary for Indian affairs, revealed in a letter to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland.

In a historical context, this report displays the federal government’s attempt to dispossess American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian people.

Secretary Haaland announced the investigation in June 2021. The primary goals were to identify boarding school locations, burial sites, and the names and tribal affiliations of children buried at each location.

Volume I of the report reveals at least one of these goals — the identification of boarding school locations and burial sites. The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) provided the Interior Department with its records and information.

For this investigation, to be identified as a Federal Indian boarding school, schools must meet the following criteria:

- Provided on-site housing or overnight lodging.

- Was described in records as providing formal academic or vocational training and instruction.

- Was described in records as receiving Federal Government funds or other support.

- Was operational before 1969.

Outside of institutions meeting these criteria, the investigation also found over 1,000 federal and non-federal institutions that may have been involved in the education of American Indian, Alaska Native, and Hawaiian Native children. More than 50 percent of these institutions were operated by religious institutions or organizations, designed to “civilize” Native children.

The investigation revealed marked or unmarked burial sites at 53 different schools. While the report states that hundreds of Indigenous children died through the Federal Indian boarding school system, the department expects that further investigation will push this number to reach “thousands or tens of thousands.”

Conditions in Federal Indian boarding schools

The Federal Indian boarding school system used “systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies” to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children. This included renaming Indigenous children with English names, cutting their hair, discouraging and/or preventing the use of Indigenous languages, religions, and cultural practices, and classifying children into units to perform military drills.

The report states that Federal Indian boarding schools often enforced rules through corporal punishment, solitary confinement, withholding of food, and more. Conditions in boarding schools were poor, rife with physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, disease, malnourishment, overcrowding, and a lack of health care — all well-documented.

According to the report, students were also forced to do manual labor and be trained in other vocational skills that weren’t beneficial in the industrial economy of the United States, which the report says further disrupted tribal economies.

“This report confirms that the United States directly targeted American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children in the pursuit of a policy of cultural assimilation that coincided with Indian territorial dispossession.”

Bryan Newland, assistant secretary for Indian affairs

Findings also mention that the Federal Indian boarding school system utilized manual labor of Indigenous children to compensate for the lack of Federal funding and for the poor conditions of schools.

Of the 408 schools identified, about 90 schools may still operate as educational establishments. However, not all 90 institutions still board children or are federally supported.

The report also cited the watershed Running Bear studies, funded by the National Institute of Health. This medical study provided quantifiable data proving that the Indian boarding school system experience continues to impact the present-day health of boarding school survivors.

Boarding schools in North Carolina

North Carolina schools revealed in the investigation include:

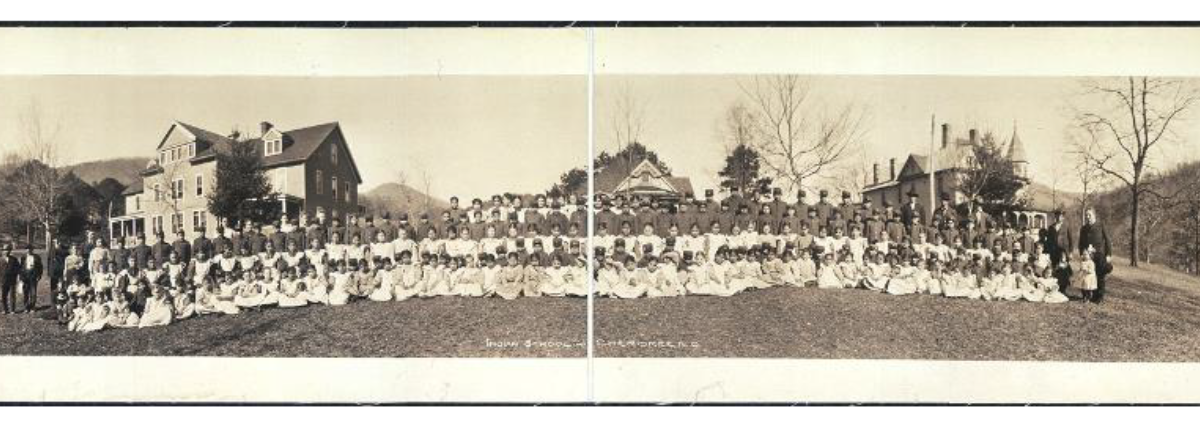

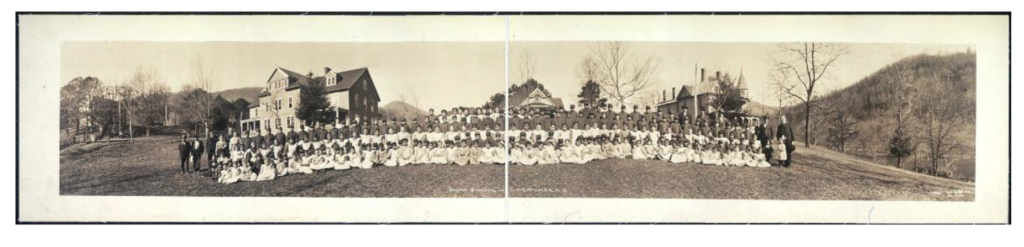

- Cherokee Boarding School in Cherokee.

- Judson College in Henderson County.

- Trinity College Industrial Indian Boarding School (Trinity College at Duke University) at its original location in Randolph County.

- Valley Towns Baptist Mission School in Valley Towns.

Opened in 1881, the Society of Friends (Quakers) operated the Cherokee Boarding School for 12 years. The school was then subsequently operated by the U.S. Indian Service from 1880 until 1954. The boarding school closed in June of 1954. Today, the Cherokee Central Schools now operate elementary, middle, and high schools as Tribal- controlled Bureau of Indian Education schools.

Judson College, located in Vance County, was identified as a training school for girls, operating until 1866.

In Randolph County, it is estimated that as many as 20 Eastern Cherokee with ages ranging from 8 to 18 attended Trinity College. Duke University still operates the Trinity College of Liberal Arts and Sciences today in Durham.

The Valley Town Baptist Mission was a boarding school that became an important center of Cherokee scholarship and resistance to Indian removal policies, rising in popularity after directors of the school began teaching and preaching in the Cherokee language. Read more about these North Carolina Federal Indian boarding schools and others in Appendix C of the report.

Jerry Wolfe, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee, shared his school experience and efforts to reconcile formal school education with tribal life in a 2005 report to the State Board of Education from the State Advisory Council on Indian Education.

“I went to Cherokee Boarding School when I was eight years old in 1932. I was always very uneasy and uncomfortable at school. It made me feel uneasy in my skin. There was always moves made and words said for no reason at all, except that we were American Indian. There was always a fright in your soul because you were afraid to defend yourself and your culture,” Wolfe said in an interview with the State Advisory Council on Indian Education. “You really got punished for speaking the Cherokee language… even being suspected of speaking Cherokee. You really got a whipping … I felt tight in my shoulders for so many years (because of the experience). It was like walking on eggshells. I was a grown man before I let the tenseness go away, before I could open up.”

Next steps

In the report, Newland included these recommendations:

- Continuing the full investigation.

- Identify surviving Federal Indian boarding school attendees.

- Document Federal Indian boarding school attendee experiences.

- Support protection, preservation, reclamation, and co-management of sites across the Federal Indian boarding school system where the federal government has jurisdiction over a location.

- Develop a specific repository of federal records involving the Federal Indian boarding school system at the Department of the Interior Library to preserve centralized federal expertise.

- Identify and engage other federal agencies to support the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, including those with control of any records involving the Federal Indian boarding school system or that provide health care to American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians, including mental health services to students attending Bureau of Indian Education operated and funded schools.

- Support non-federal entities that may independently release records under their control.

- Support congressional action.

Secretary Haaland also announced the launch of “The Road to Healing,” a year-long tour that will include travel across the country and allow survivors of the Federal Indian boarding school system to share their stories, provide communities with trauma-informed support, and facilitate the collection of a permanent oral history.

“Recognizing the impacts of the Federal Indian boarding school system cannot just be a historical reckoning. We must also chart a path forward to deal with these legacy issues,” Haaland said in a press conference on Wednesday.

The report promises a second volume, which will include determining locations of marked or unmarked burial sites associated with the Federal Indian boarding school system, identifying names, ages, and Tribal affiliations of children buried at such locations, and approximating a full accounting of Federal support for the Federal Indian boarding school system. Congress appropriated $7 million in new funds to support this second volume.

Correction: This article originally stated that Judson College was located in Henderson. It is located in Henderson County.

Correction: This article originally stated that Trinity College Industrial Indian Boarding School was located in Durham. Trinity College Industrial Indian Boarding School was located at Trinity College’s original location in Randolph County.

Recommended reading