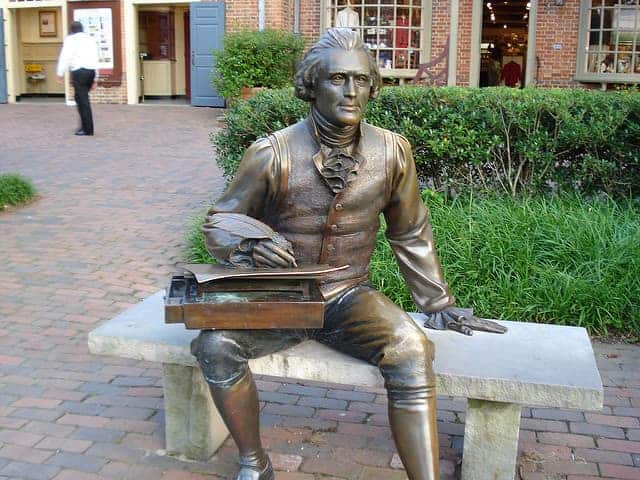

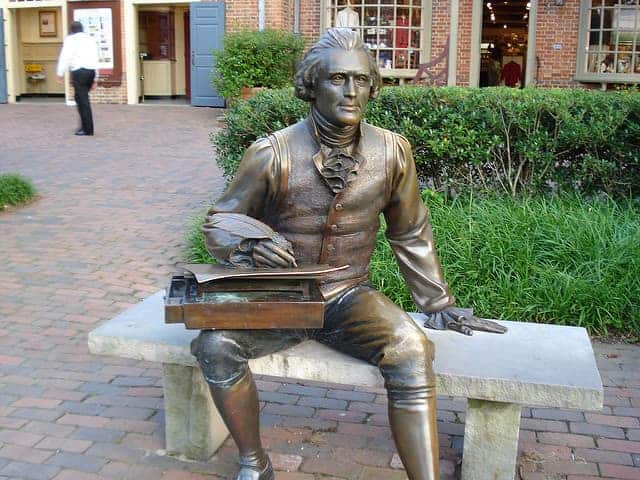

On June 14, 1760, 17-year-old Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to the executors of his father’s estate asking for the money he needed to enroll at the College of William and Mary. It is the oldest surviving letter written by the nation’s third president.

Alan Taylor, who has won two Pulitzer Prizes in history, highlighted the teenaged Jefferson’s letter in a recent lecture at the National Humanities Center in Research Triangle Park. Taylor drew from research for his book-in-progress on education in the age of the American Revolution.

The story Taylor told, as expected from a skillful historian, lends perspective to the great debates over public education in the age of President Donald Trump and of partisan polarization in the states and the nation. Tensions over the purposes of education date “back to the very origins of the Republic,” said Taylor, who holds the Thomas Jefferson Memorial chair in history at the University of Virginia.

“In every generation in our history,’’ he said, “there has been a struggle between people who want an education that conserves, that preserves the status quo, and the people who want an education for people which will create something different, imagined to be something better.”

In addition to winning independence and creating a union out of 13 colonies and the frontier territory stretching to the Mississippi River, the founders wanted to establish a republic in which citizens would select their public leaders through voting. As Taylor explained it, the founders, as educated men, knew from ancient history that republics had failed as a result of “bitter class divisions and reckless political demagogues who pandered to popular prejudices.”

“In order to avoid this nightmare scenario,” Taylor said, “the leaders, almost all of them, said the key is education – that you needed to have an educated electorate that would be capable of discerning the reckless demagogues from the virtuous politicians.”

In the 18th century, Taylor explained, virtuous referred not so much personal rectitude as the capability to put aside self-interest and pursue the common good. “Unless people were educated in virtue,” he said, “you could not sustain the republic.”

As governor of Virginia, Jefferson proposed a three-tiered education system: local grammar schools for boys and girls, county-level academies (high schools) for boys, and a state university for potential societal leaders. Jefferson did not envision education for slaves or free-blacks, nor for girls beyond grammar school.

Jefferson’s plan won little support from the Virginia assembly, and had little public support as well. Neither state legislators nor county officials wanted to raise taxes for schools. Taylor quoted a “rustic’’ who said, “who wants Latin and Greek and abstruse mathematics in a country like this?” And Taylor added in an aside, “This is from the early 19th century; this is not a recent quote.”

Drawing from Jefferson documents, Taylor said that, despite being thwarted in his education initiative, Jefferson saw education as a catalyst to “promote social mobility and greater equality.” After his presidency, Jefferson turned his attention to establishing the University of Virginia, founded in 1819 in Charlottesville.

Town-based public schools had spread through New England in the colonial and early-independence periods, decades before the mid-Atlantic and Southern states would take public education seriously. The nation’s transition from an agricultural to an industrial-and-service economy propelled a vast expansion in education. And, as Taylor said, it shifted the rationale for schooling from supporting the republic as a society to bolstering the economy – from political virtuousness to economic growth.

“This shift,” he said,” has led people increasingly to define education as a private and individual benefit rather than as something that contributes to the public good.”

Reflecting the temper of the times, contemporary advocates for public education find themselves drawn to economic arguments – the more you know, the more you earn – as what it takes to persuade public officials. Still, it is important to reaffirm that, from the outset of the nation, American schools have had a sustain-the-republic imperative.

Taylor concluded, with a touch of wistfulness, “So we are in retreat from Jefferson’s dream of expanding education opportunity for all.”