Launched in 2015 by Family Services, The Forsyth County School Readiness Project (FCSRP) is an effort to equip preschool teachers in seven Head Start classrooms with the skills they need to better teach children self-regulation and executive function, all critical tools for success in school and beyond.

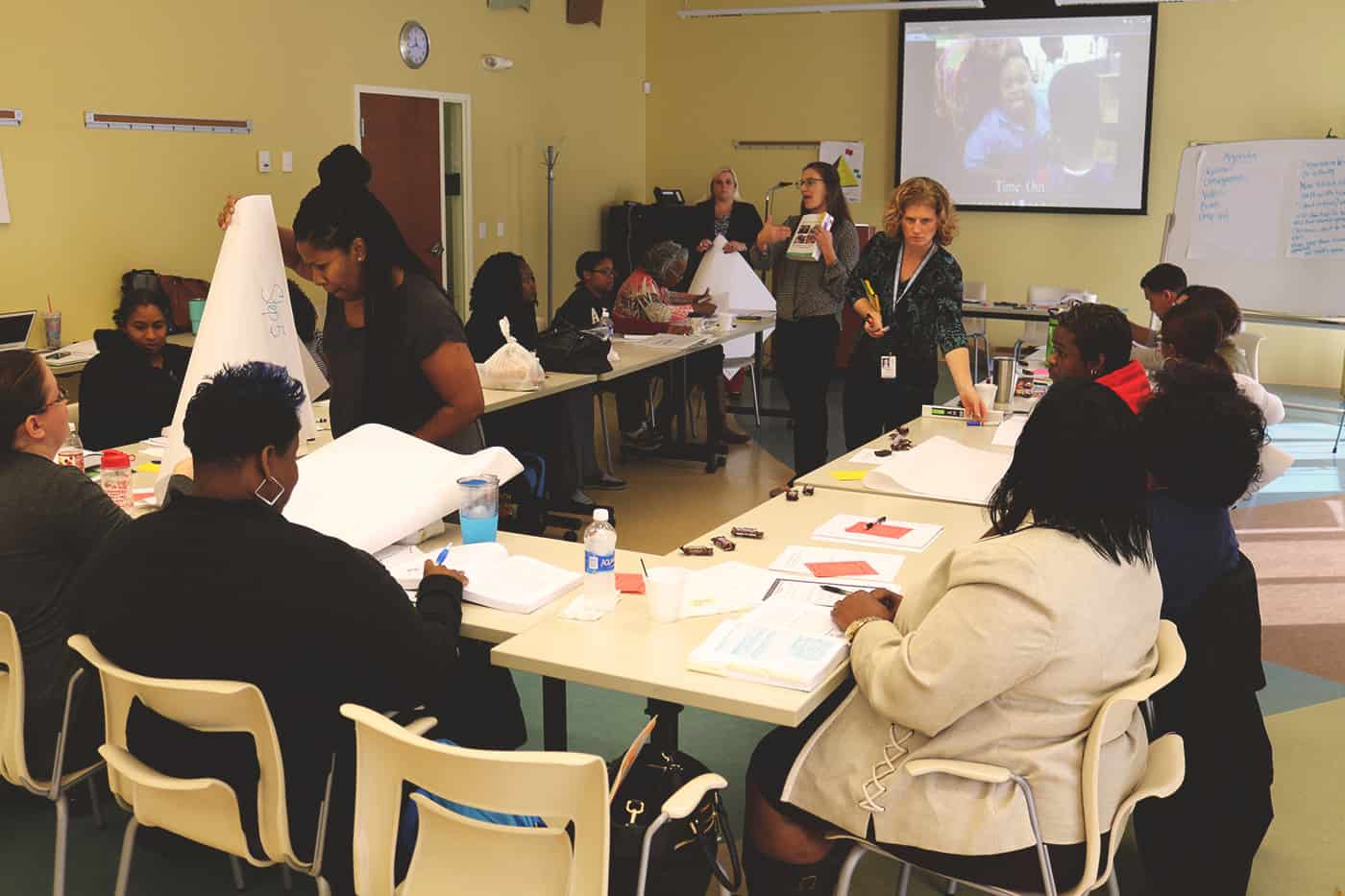

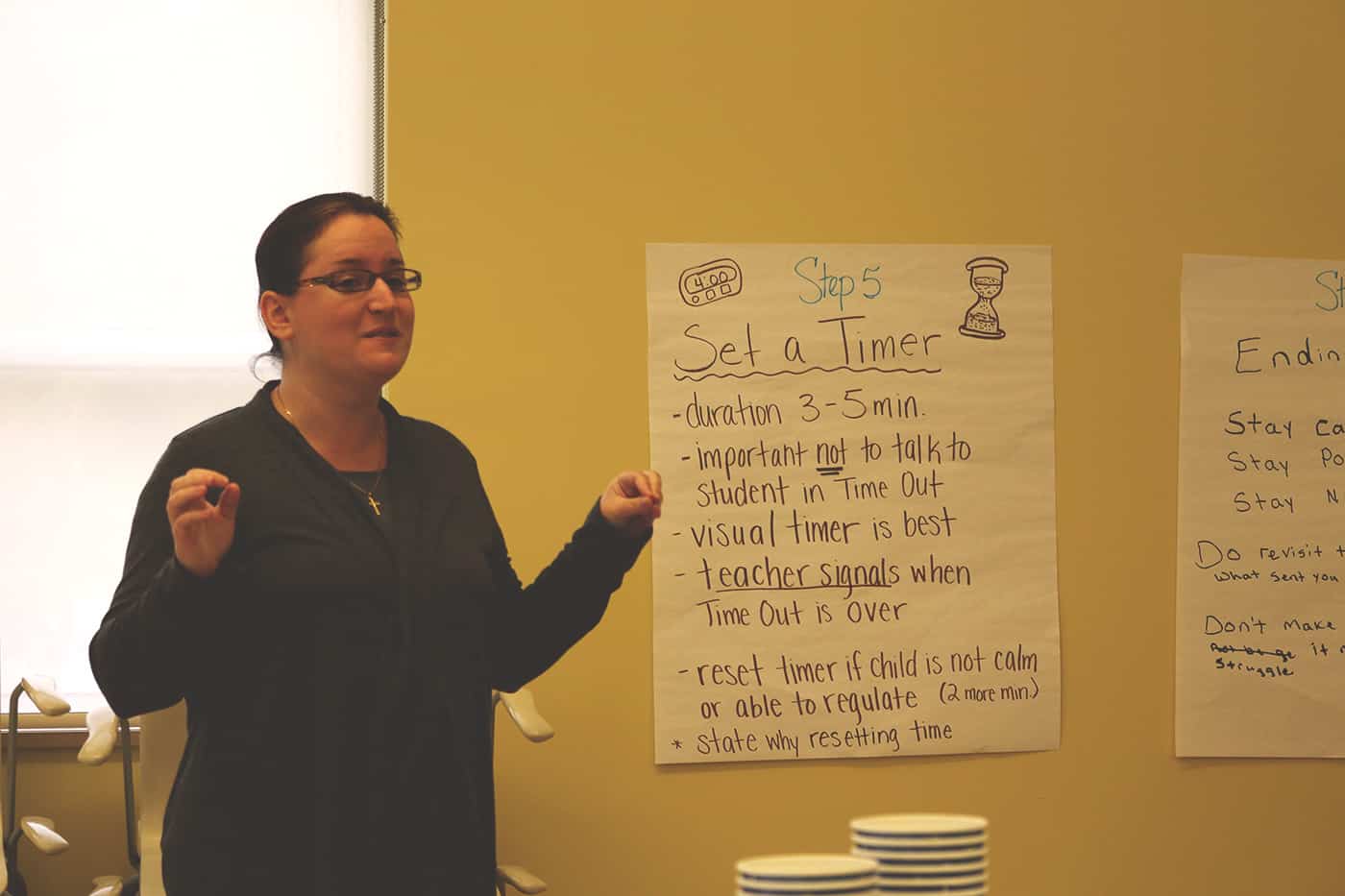

In November, teachers participating in the program gathered at the Family Services offices in Winston-Salem to participate in extensive training in the Incredible Years Teacher Classroom Management Curriculum. It was a chance for teachers to learn new skills, hear from experts in the field, and network with their peers.

In its first year of existence, The Forsyth County School Readiness Project has served seven Head Start classrooms, with a total of 119 children. Sixty-four percent of those children are African American, 27 percent were identified as multi-racial, and nine percent were Hispanic. Ninety percent of the children meet the eligibility guidelines for Head Start services, meaning they come from families with incomes below the federal poverty level.

The project provides teachers with 30 hours of skills training and professional development to promote self-regulation practices and avoid disruptive behavior in the classroom setting. It includes access to mental health coaches who provide 130 hours of classroom observation and teacher coaching during the school year.

Participating teachers are also given stress-reduction training to assist in improved classroom management and their own self-regulation. Teachers can also refer students with persistent behavioral problems to the program’s mental health coaches. Coaches are made available to meet directly with those students and their parents to provide more in-depth support.

The Forsyth County project is modeled after Dr. C. Cybele Raver’s Chicago School Readiness Project (CSRP). Dr. Raver is serving as a consultant to The Forsyth County School Readiness Project team.

A key component of the program is the availability of the mental health coaches both to teachers and families.

“It’s kind of an interesting role,” said Casey Combs, one of the program’s mental health coaches. “Our background is we are licensed therapists. We come from a counseling model in an office setting, just one-on-one with kids of all ages.”

For Combs, one of the most important aspects of her work is the support she and the other coaches provide directly to the teachers they work with.

“A lot of our role is just encouraging teachers and telling them that they’re doing a good job, which they are, but a lot of times they don’t hear that enough,” Combs said.

Sometimes that means admitting a certain child’s situation is difficult and that it will take a team effort to help them learn self-regulation. And sometimes that means working directly with the parents.

“That’s probably the biggest difficulty for this population,” Combs said. “Toward the end of the year we do some more one-on-one work with the kids that are still struggling, with some stress management things built in for the teachers as well.”

That means Combs spends four-to-five hours each day with one of her four classes. It’s a presence the teachers learn to depend on to offer support and encouragement.

That can mean anything from an in-depth consultation on a problematic student, to helping a teacher clean a classroom.

“We’ll do some brainstorming or I’ll help clean the tables,” Combs said. “We’ll help serve lunch — just anything to help. If a kid is having a hard time at circle time, we can take him out to a different spot or really whatever they need.”

The type of support highlights the partnership philosophy of the program, one where the coaches rely upon the expertise of the teachers they work with to learn more about the students and families they are helping. It is clear the mental health coaches in the program view their teachers as peers and partners in their collective work.

“They’re teaching us,” Combs said. “They know about their kids, they know about their families, they know where they are coming from. They can really relate to these children. That’s really a gift that these teachers have.”

For Mental Health Coach Raquel Henkel, the support is essential for managing students from high-poverty backgrounds who may be dealing with significant environmental stressors outside the classroom — stressors that follow them into the school and may impede their ability to self-regulate.

“They’re much more unregulated than what I see in a typical child-care setting,” Henkel said. “You don’t really know what they’re going through. Some you can just guess based on what you hear from the parent.”

Many of those students need assistance in self-regulation, skills that no one has ever taught them or modeled for them.

“There is a sense that the kid should just be able to calm himself down and do the right thing,” Henkel said. “We do coaching; coaching the child in how to calm himself down. We do a lot of lessons using puppets on different friendship skills. Calming down using breathing strategies…just teaching them things that they might not know and that their parents might not know.”

That means working directly with parents of students who are having an especially difficult time. “We know that if we don’t have the parent’s engagement, long-term results for the child is not going to be very good,” Henkel said.

Even for the most experienced teachers in the program, the training and support of the mental health coaches has been a learning experience and has taught them new skills for classroom and student management.

“It allows me to think outside the box,” said Tamika Howell, a preschool teacher with 22 years of classroom experience. “Programs like this are great. I’ve received articles recently how [discipline] affects our at-risk children who are living in poverty. Expelling or suspending children takes the chance on them dropping out in high school and increasing their chances of being incarcerated.”

For Howell, the focus on the student’s background and the skills they may need to be successful in the academic setting means working with both the parents and the child. “We just have to keep the family as a whole in mind as we work with the child,” Howell said.

For Shelby Moody, a teacher with 16 years of preschool classroom experience, the program has helped her appreciate the conditions her students are living in and better support their parents. That means being a support for them as they try to improve their own lives. It has also helped her manage her own stress in the classroom.

“There has been so much information to help me in such a short time,” Moody said. “I’ve learned how to stay calm. Stay positive.”

“One thing I’ve always been taught is that to teach children, you have to have structure, you have to have control, and if you give them the control, then all your strategies are out the door,” Moody said. “That’s one thing that I’ve learned. I’ve learned to stay calm with those difficult parents.”

“Head Start is about the entire family — getting them from one point to a higher area of success,” Moody said. “We have great success stories, but you meet that one parent that is a brick wall. It’s hard to tear down…it really does take a village. Not just for the child but for the family. They’re lacking in so many areas. We have so many parents that are either in shelters or living with other family members. They just don’t know how to get out. That’s where we come in. To help them fight out. Keep giving them encouraging words and strategies. Some of them do get it.”

Moody will admit it is not easy being a preschool teacher. She will tell you that she and her peers are not paid enough, and are frequently not appreciated for the role they play in their communities. But she knows the difference she is making in the lives of the children she teaches and their families.

When asked what advice she would give someone just entering the profession, Moody is quick with an answer: “Don’t give up. Don’t throw in the towel. ”

“Last year, I literally went home crying asking myself if I’m in the right profession,” Williams said. “Is this what I’m suppose to be doing? You’ve got to have compassion to work with these children and parents. You have to be a server to be doing this stuff.”

Like Moody, Marilyn Dunlap has made a career in the preschool classroom. For 39 years, Dunlap has worked with young children, helping prepare them for success in school and beyond.

“It’s a passion. It’s my gift. I love it,” Dunlap said. “To me it’s not hard work. I never saw it as hard work.”

Dunlap sees every parent as wanting the best for their child. “No matter where you come from, everyone wants their child to succeed,” Dunlap added. “Every parent wants their child to be happy, healthy, and successful.”

However, parents from low-income backgrounds are often dealing with issues other parents do not have to face. That means they may not have the time or resources to provide for their children. That means an extra layer of stress and guilt.

“A lot of them have become parents at such a young age,” Dunlap said. “We’ve got a lot of parents that are going back to school, because a lot of them did not finish their education. They have stress. Then they have their children that they have to take care of and be a parent to. This program gives them tools to work with so they won’t be so stressful.”

Dunlap works to empower the children in her class, to give them the skills and positive self esteem they need to be successful.

“Children want order,” Dunlap said. “If you give them responsibility, if you let them know you can trust in them, and know they can do it, [it will] build that self esteem. Before you know it, you’ve got a supervisor in your classroom.”

“You have to keep them with kindness and love and be there for them,” Dunlap said. “You’ve got to be dependable.”

Dunlap sees opportunities for professional development offered by the The Forsyth County School Readiness Project as being critical for keeping beginning teachers in the profession.

“We don’t know everything. We’re still learning,” Dunlap said. “I tell them to go to workshops, get journals, because there are always new ideas. There’s always different ways. If they keep getting these opportunities, then these young children will continue to stay in this profession.”

For Shelia Ebrahim, a center manager with Family Services who is part of the FCSRP team, for preschool classrooms to retain a cohort of professionals, community leaders and policy makers need to better understand the important role those teachers play in nurturing young minds and the contribution they make to the larger society.

“First of all, [policy makers] need to visit an early childhood classroom,” Ebrahim said. “When we’re talking about the lives of children and families who have not known anything but the system and living on the system…they need to realize there needs to be training programs available for success. Reasonable accessibility so that they can someday sustain their own lives. They are parents to those children. That what we do from birth through K makes a difference in our world and our country.”