John B. King may have never become secretary of education under President Barack Obama if it wasn’t for school — and not just because of what he learned in the classroom. King lost his mom at 8 and his dad at 12 and said going to school in New York City was his refuge from the turmoil of his life at home.

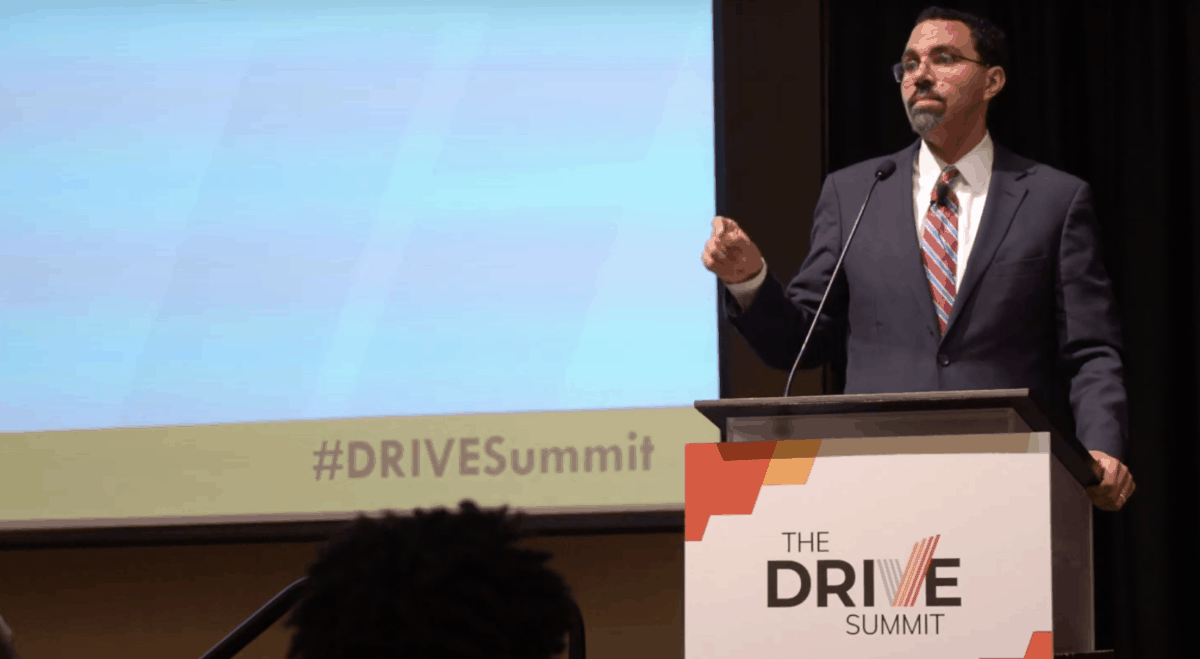

“The thing that saved me, the reason I’m standing here today, is I had a series of phenomenal New York City public school educators who made school a place that was safe and nurturing and engaging,” he said. “A place where I could be a kid when I couldn’t be a kid at home.”

Now president and CEO of The Education Trust, King said that having a teaching force that reflects the increasingly diverse student populations of the United States is key to the success of our entire country.

“The potential here is not just about diversifying the teacher workforce today. This is about the long-term health and well-being of our economy and our democracy,” he said.

King gave the keynote at the DRIVE Summit Tuesday, which brought together stakeholders, leaders, and thought experts to talk about how North Carolina can get more teachers of color in the classroom. The event was co-hosted by the Office of Gov. Roy Cooper, The Hunt Institute, and the NC Business Committee for Education.

King told the crowd that he remembered one teacher of color who had a particular impact on him: Miss D., his seventh grade social studies teacher at Mark Twain Junior High School in Coney Island.

At this point, he had already lost his mother, and his father was suffering from undiagnosed Alzheimer’s. King bore a lot of responsibility.

“I was basically keeping our household going,” he said. “I was figuring out how to get food in the house. I was figuring out how to pay bills.”

He never knew how his dad was going to be: sad, mad, silent. While he was in school, he would often sit and wonder what he would come home to. He did that in every class — except Miss D.’s.

“Miss D. inspired me. She was one of the first teachers of color that I had,” he said. “And in her classroom, there was a sense of safety and a spirit of learning that was transformative.”

After King’s keynote address, he sat down and talked with Rodney Robinson, the 2019 National Teacher of the Year. Robinson echoed the importance of teachers of color, pointing out how fortunate he was to have one for both third and fourth grade.

“I know the students that were in those classes. Most of us went on to college; all of us graduated high school,” he said.

His fellow students of color who didn’t get exposed to the same teachers weren’t so fortunate, he said.

Even more impactful, perhaps, was the assistant principal who came into his school during Robinson’s 12th grade year.

The assistant principal was hired in the aftermath of two discrimination lawsuits that happened during Robinson’s 11th grade year. The hiring of the black assistant principal was an attempt to placate the NAACP, Robinson said.

That man — Dr. Lewis — had a profound impact. Robinson described an incident his senior year when a teacher said something racial to him, something that he might have ignored in previous years.

“I was a senior, so I was a little tired of it,” he said.

He turned his desk over, said some choice words, and got sent to the assistant principal’s office.

Lewis sat Robinson down, and instead of launching into a discussion about Robinson’s behavior, the assistant principal asked him where he was going to college. The assistant principal went on to tell Robinson about Virginia State University, a college that he said molded him from a “confused teenager to a confident man.”

When the conversation was over, Lewis finally brought up what Robinson had done in class. Instead of sending him home, he gave him five days of in-school suspension.

On the first day of suspension, Lewis came in and helped Robinson fill out his application. The second day, he helped Robinson with financial aid. The third day, he helped Robinson find alumni associations and scholarships.

“I had all the other white teachers tell me about college,” Robinson said. “But I didn’t know anything about the college process.”

The assistance continued even after Robinson left high school. Lewis would show up at school Robinson’s freshman year and take him out for a home-cooked meal.

During his keynote, King talked about the research surrounding the impact of teachers of color on students like Robinson and himself. Having a black teacher in elementary school just one time can have an impact on the likelihood that a student of color will drop out.

“You’ve heard the research. We know the difference,” he said. “And yet we are not doing the things that are necessary.”

He talked about North Carolina and the realities of the teacher workforce we have. He pointed out that in Wake County Schools, there are nine white students for every one white teacher. By contrast, there are 25 black students for every one black teacher. In Asheville City Schools, there are nine white students for every white teacher, and 56 black students for every black teacher.

For Latinos, it’s even worse. In Wake County, there are 100 Latino students for every Latino teacher. In New Hanover County, 117 Latino students for every Latino teacher. In Charlotte, that number jumps to 169.

And, he said, the stakes are high. Having a teacher of color can impact a student of color’s chances of getting into advanced classes. It can lessen their chance of disciplinary punishments.

Even in pre-K, King said students of color are more likely to be suspended. And that has an impact not only on students, but also on teachers of color.

“If you’re in a school where the message to 4-year-olds is, ‘School is not for you. Get out of here.’ That’s sending a message to that 4 year old about teaching; that’s sending a message to teachers about teaching,” he said. “That’s sending a message that rejects teachers of color and communities of color.”

That can add to a climate that makes teachers of color less likely to come into or stay in the classroom. Climate was one of the four “homework assignments” King gave the audience. He asked them to think about school climate, data transparency, retention, and improving the pipeline when it comes to teachers of color.

King said that if the public education system nationally and in North Carolina can get it right, it would have big implications for the future.

King told an anecdote. A Latina teacher in a math department at a middle school where he was a principal had a student from Cape Verde. That student started a math peer tutoring program under the teacher’s tutelage. Ten years later, King came back to visit, and that student was the teacher. A little later, she became principal of that school.

That’s a story not just about the student, but also about the impact of her teacher, King said. A story that could be duplicated in classrooms around the country if students have exposure to people they can connect to and draw inspiration from.

The majority of kids in public schools are students of color and students who are eligible for free- and reduced-price lunch, King said.

“If we fail as a country to educate low-income students and students of color, we have no future,” he said. “But if we do that work, if we create school communities that are strong, healthy environments for teachers of color and students of color and school leaders of color, we have the opportunity to build an even stronger democracy and even more prosperous future.”