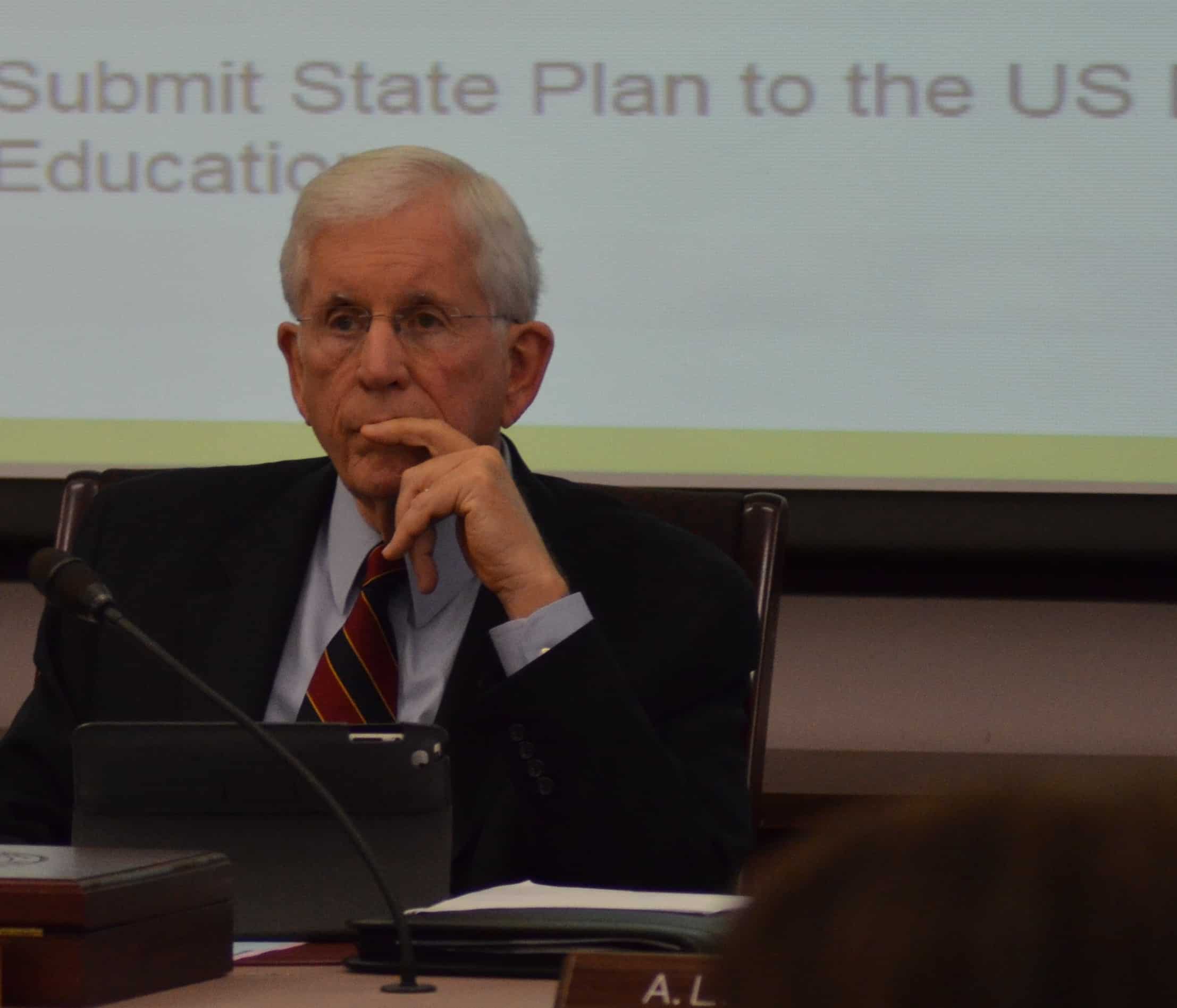

Bill Cobey now serves as chair of the State Board of Education, a capstone to a long, diverse career, much of it spent in the public sector. To review Cobey’s career is to put in perspective the court case arising from the legislature’s reassigning of decision-making powers in education in North Carolina.

Cobey’s leadership makes clear that this case is not simply another episode of a Republican legislature vs. a Democratic governor. It is not simply an inside-the-Raleigh-beltline maneuver of little import to the state’s citizens. The case, indeed, has wider implications for how public schools are governed, and for the ability of the state to advance in providing a sound basic education to its young people.

Cobey was athletic director at UNC-Chapel Hill from 1976 to 1980, the year in which he became the Republican nominee for lieutenant governor. He lost that race, but then won a two-year term in the U.S. House in 1984. After losing his House seat to Democratic U.S. Rep. David Price, Cobey held the cabinet post of Secretary of Environment, Health and Natural resources in Republican Gov. James G. Martin’s administration.

In addition to serving as Morrisville town manager and chair of the state Republican Party, Cobey ran for and lost the Republican nomination for governor in 2004, when Democrat Mike Easley won re-election. He spent seven years as a presidential appointee to the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority, and was appointed to the North Carolina education board by former Gov. Pat McCrory.

There is, then, no doubting Cobey’s Republican bona fides. Moreover, his career demonstrates a persistence in sustaining political and public institutions.

Shortly after the General Assembly’s Republican-majority enacted, in one of its December special sessions, a measure shifting an array of decision-making authority from the State Board of Education to the Superintendent of Public Instruction, Cobey raised an objection – and he led the board to challenge the legislation in court. The essence of the case hinges on the state Constitution’s provision that gives the State Board of Education the duty to “supervise and administer the free public school system.’’

For decades, North Carolina officials have tussled over the relationship of the Superintendent of Public Instruction and the Board of Education, as well as debated whether the superintendent ought to be a gubernatorial appointee rather than a statewide elected official. In 1987, during a Republican governorship, the state Senate, with a Democratic majority, voted to make the office appointive, but the measure died in the House. In 1995, the legislature passed a law giving the board authority to define the superintendent’s job. In 2009, when Democratic Gov. Bev Perdue sought to install an appointee as the system’s CEO, Democratic Superintendent June Atkinson challenged the move in court, and won.

From a purely governmental perspective, it’s hard to see how the administrator of the education department is substantially different from the administrator of the transportation, commerce, health and human services, and other departments and agencies under a governor’s administration. Of course, a constitutional amendment would be required to shift the superintendent from an elective to an appointive official. And a veto-proof Republican legislative majority surely won’t propose such an amendment while it is also trying to limit the new Democratic governor’s powers.

The state board consists of 11 gubernatorial appointees — who are confirmed by the legislature and serve eight year terms — plus three ex officio members: lieutenant governor, state treasurer, and education superintendent. Clearly, GOP legislators had in mind shifting power away from a board that Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper will soon populate with his appointees, and handing more clout to the new Republican Superintendent Mark Johnson.

Education represents such a huge segment of the state General Fund, and better schools are so central to North Carolina’s future, that strong leadership from a governor is essential. The Superintendent of Public Instruction, whoever holds the office, cannot match a governor in public visibility, political reach, or institutional heft.

Even as he faces an opposition legislature pursuing an agenda that promotes school choice including state aid to private schools, Cooper has an opportunity to demonstrate anew the potency of gubernatorial leadership in education agenda-setting. And in his late-career decision to resist a Republican power maneuver, Bill Cobey offers a lesson in balancing party loyalty with playing by the rules of law and constitution.

Recommended reading