As public discourse about education policy turns to teacher pay, lawmakers look to data points for guidance. North Carolina uses the Education Value-Added Assessment System, or EVAAS, as a way to track student performance and evaluate teaching. The system, developed by SAS, has been creating data points for teachers in North Carolina since 2013. Though no one that I have asked seems to know exactly how the sausage is made (perhaps it is proprietary), I can tell you this:

If EVAAS will be used as the basis for determining teacher pay in North Carolina, and they want teacher buy-in, policymakers may first need to start with an apology to teachers. I’ll be the first in line. Here’s my story:

When I first heard about EVAAS, I was actually a bit excited. It seemed like a statistically valid model; you take the students’ historic testing data (past performance) and predict their future performance. Then, you test the students and see if the teacher took them as far, not as far, or farther than expected. It would be just one data point, but I liked that it was based on growth. It tracked how far I took a student, not just if they met an absolute competency standard.

Also, in my mind, it might answer an existential question I had carried for most of my professional life, THE question: Am I really a good teacher? I had received an award or two and had a good reputation in my school and community, but I sometimes feared that was just based on esoteric factors like charisma or enthusiasm. Deep down, I feared the emperor had no clothes. This would be an indicator that might lay my mind to rest. It would be nice to know that I am enthusiastic, caring AND I impart measurable, standards-based, content mastery to my students. I love my content area (social studies) and I am a “true believer” that I am creating citizens capable of carrying our democracy forward.

The specter of EVAAS did not change the way I taught. I was already doing everything I knew to do. Scaffolded instruction, flip videos, strategic grouping, daily writing, tailored vocabulary activities, remediation . . . these were all methods I employed that required endless hours of prep and feedback, but I had a lot of confidence in them. With these research-based and time-tested methods plus a commitment to stay on pace in my curriculum (11th grade American History II), I taught my students the best way I knew how.

Those particular classes were a challenging bunch that year. Both of my classes in that subject (my other class was an elective, therefore it did not have a state test) were lower level; motivation and prior knowledge were lacking, but most of them were good kids who just needed a lot of support. I even had a special educator in one of those classes with me every day, so I didn’t see how we could lose. I reasoned, if we are going to measure growth, this will be a piece of cake, because there is a LOT of room for growth here.

It also happens that, in the fall of 2013, a documentary film crew started following me around. They were wanting to make a film about teacher performance. They thought I would be an interesting subject and I was happy to participate, hoping we could launch a more nuanced conversation about teaching and learning in the state. It is titled, “Teacher of the Year,” and was produced by At Large Productions.

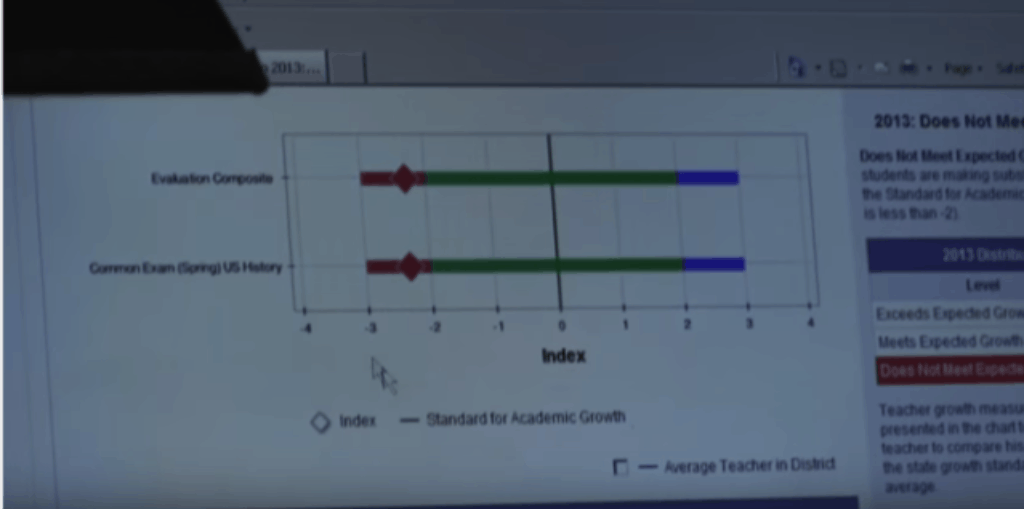

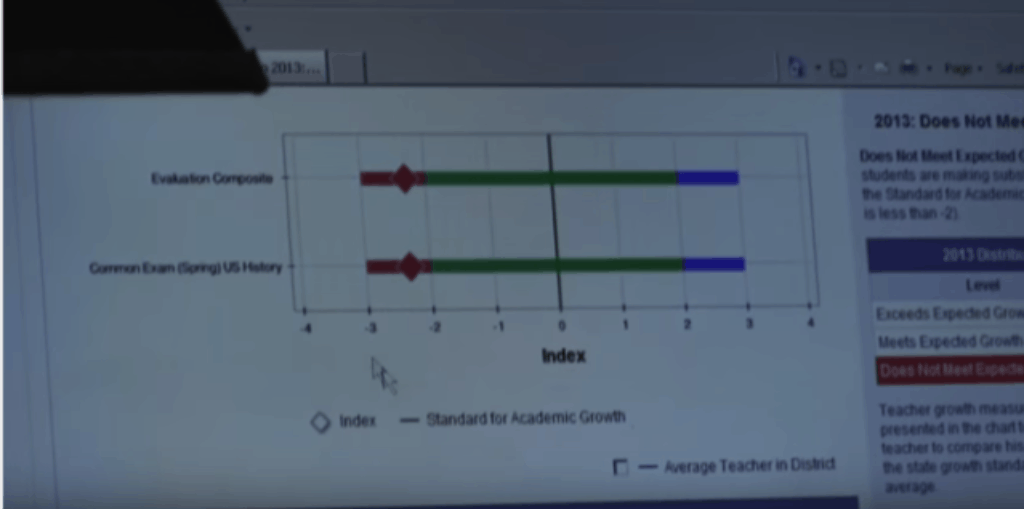

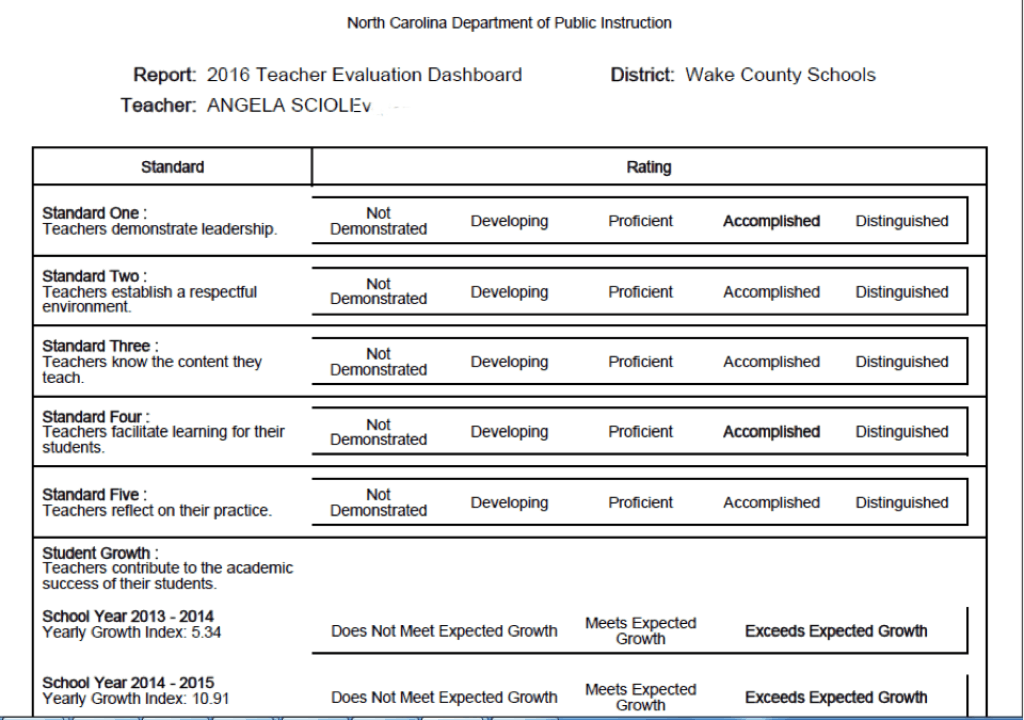

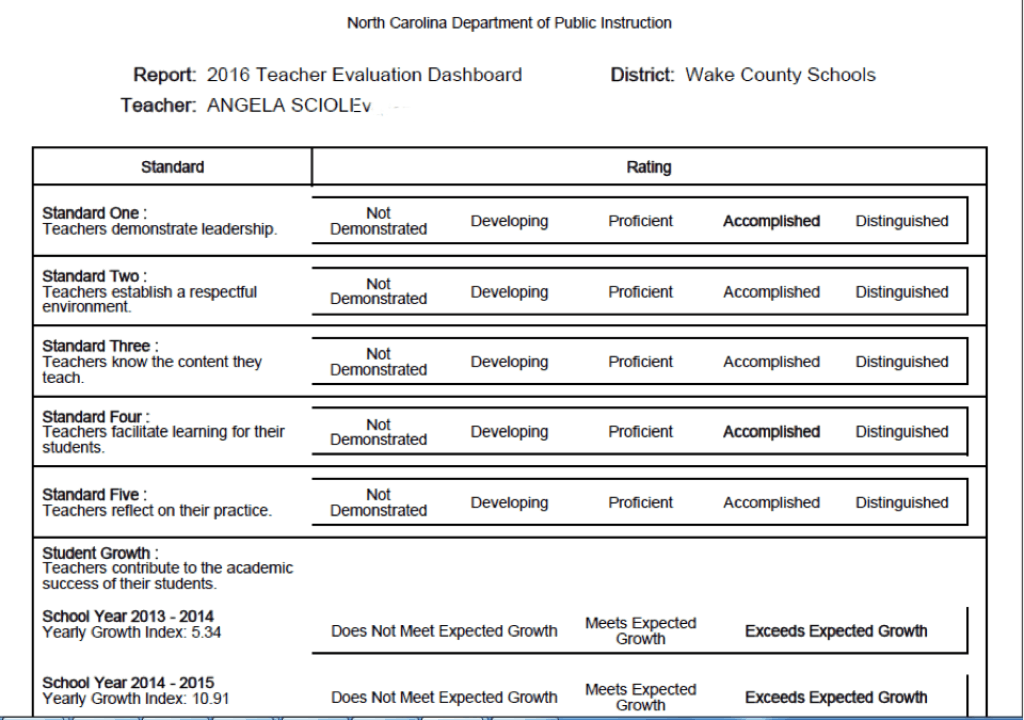

I did not anticipate that they would capture on film that my EVAAS scores were really bad. I was, as you can see here in screen shots from the film in spring of 2014, rated as highly ineffective at teaching my subject. In the red. Deep in the red.

I was shocked. I was embarrassed. And I was stuck. I really didn’t know what I was doing wrong. Was I too demanding? Was I not nurturing enough? Was there some glaring inadequacy in what I was doing that I had not seen? I thought and I pondered; I checked in with the special educator who had seen me teach every day for years, and we both came up with nothing. Not only did the emperor have no clothes, she couldn’t even find the closet. I resigned myself to being more loving and nurturing to my students – that’s the only thing I could think of – and I humbly went back to my task the same year.

I did not change anything else about my teaching. I did not know what to change. No one met with me to intervene. No one even spoke to me about the results. It just sat there, like a black eye I couldn’t cover up, but no one wanted to talk about it.

The next year, I received my EVAAS results, after using the same methods, and I was now deemed “highly effective.” I was relieved and confused. How could that be?

At that point, I checked out on the EVAAS model. It lacked integrity to me, to be honest. It just did not make sense to me that I could be the same teacher, using the same methods, and in one year, I was deemed a failure and another year, I was deemed a success.

But recently, my apathy turned to anger. I had told this story enough times that I decided to access my EVAAS reports from years past to more clearly make my point. EVAAS reports are only available during short windows of time, so I waited for the access window to open. After a couple (typical) technical glitches (my “report” button would not actually work), I finally logged in. Imagine my shock when I accessed my report, and it now said this:

Notice under “School Year 2013-2014” my results now say “Exceeds Expected Growth.” I am not sure how to square that circle. Perhaps they have “re-normed” that year. Perhaps there is some seemingly rational explanation for this revised report. I just know I was not aware of it, and that in the meantime, I beat myself up and searched my mind and heart to solve a problem that might not have ever existed.

There are a lot of ways in which teaching feels like an abusive relationship. I feel such all consuming passion for what I am doing. I am strangely isolated. I am constantly seeking affirmation that I am doing a good job. I often do not feel respected by people in power, and I am sacrificing so much personal health and family time to do this job well. But, hard as it is to admit, I just can not walk away.

Nevertheless, after experiencing the pain this EVAAS process caused me, and now seeing it papered over, I know this for sure: What happened is not right. And I will not soon forget it.

The state of North Carolina should be glad it was just my self-concept and pride, and not my paycheck, riding on my 2013-14 scores. Because instead of me having a healing metaphorical black eye, they might have a class action lawsuit on their hands. But this much is clear: the current system is not fair, not transparent, and it does not ensure that we teachers will know, in the immediate term and in the longer term, if we are effective teachers.