What is the value of a dollar?

Jermaine Porter, equity leader in the Durham Public Schools, uses that question as an exercise. First he transports you to a vending machine with two dollar bills. One is crisp and clean. The other he crumples, throws to the ground and spits on. He tells it that it will never be anything.

That crumpled dollar is the Black student who is suspended or referred for juvenile action — something that happens at alarming rates. It’s the student with learning differences who lives with the stigma of being lesser or lazy. It’s the LGBTQ student who is misunderstood, confused, and at higher risk of suicidal thoughts. It’s the Latinx child who feels torn between living authentically and assimilating into a white culture.

When you’re standing in front of the vending machine, you may be inclined to give the crisp, clean bill the “opportunity” to work for you. But never forget, Porter says, that the crumpled dollar is worth the same amount. It just might need a little more attention — to unravel, smooth out, and be given a chance.

That’s the equity work.

“We have to be able to give all students the same opportunity,” Porter said last week at the NC Conference on Educational Equity, hosted by The Friday Institute. “The same opportunity you were willing to give to the dollar that hasn’t been through anything should be given to the dollar bill that had been ripped up, balled up, and put on the ground.”

Panelists at the conference over two days talked about ways to bring equity practices into schools. Here are six examples.

1. Suspension and criminal justice

The ways that educators interact with students, particularly those from historically marginalized communities, could be triggering a Pygmalion Effect, author and consultant Tru Pettigrew said.

“When we expect certain behaviors of others,” he said, “we are likely to act in ways that make the expected behavior more likely to occur.”

Porter and his colleague Daniel Bullock from the Durham Public Schools’ Office of Equity Affairs talked about the importance of breaking the relationship between implicit bias and the disproportionate suspension rates of Black students — who are suspended 4.1 times more than white peers in North Carolina.

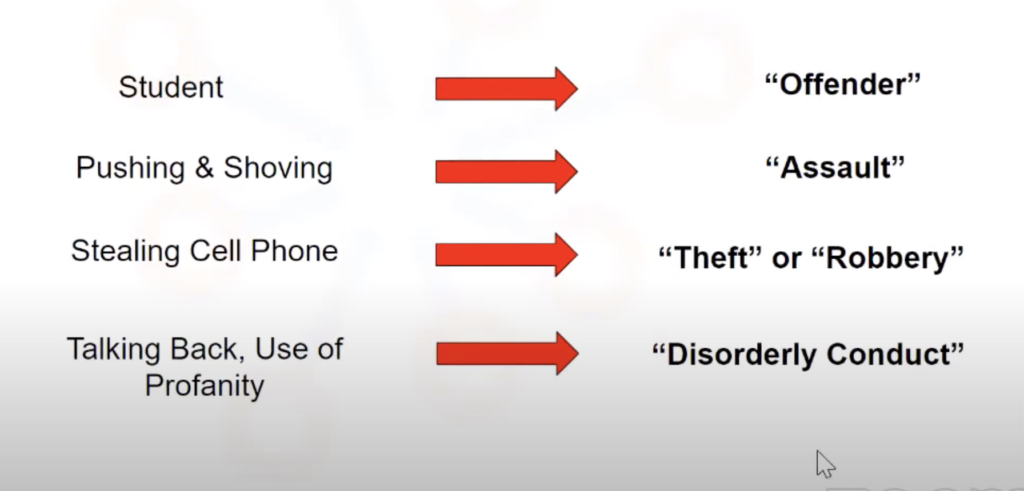

Criminalization of Normative Adolescent Behavior

How do you disrupt this relationship? Jen Story of Legal Aid and Barbara Fedders of the UNC School of Law suggested reframing questions around suspension and punishments. Rather than asking whether a child accused of misconduct did the act, start by asking why that child is struggling in school.

“What is the goal?” Story asked. “And what goal is advanced by a chosen response to misbehavior?”

Those questions are especially important when a teacher may be operating under implicit bias. Bullock and Porter challenge educators to call out implicit bias when they see it — and not let too much time go by before addressing the matter.

They offered four strategies: questioning bias when it’s seen, interrupting the process between bias and reaction, educating colleagues, and echoing the messages of those in your school fighting implicit bias. You can hear more about this advice starting at 38:30 here.

If a school decides to suspend a student, several panelists said, there should be a reentry plan first. While that student is suspended, school keeps going, and the student falls further behind. And in the discomfort of feeling behind on return, the student will seek comfort — perhaps in ways perceived as behavior problems.

“If you don’t [have a reentry plan], what’s going to happen is recidivism,” Porter said. “That same teacher that they cussed out when they were suspended several days, do you want to put them back in that exact same classroom without having a conversation with them? That makes no sense.”

2. Equity through curriculum

Rethinking curriculum for every child is neither easy nor quick work, but several panelists said few changes in schools would have as big an impact on equity.

Mitzi Safrit and Patrice Hardy of Wake County Public School System talked about establishing classroom settings where students feel accepted, worthy, and valued. They talked about fighting implicit bias and holding every child to high expectations. For Black male students, specifically, they spoke of developing a positive and genuine relationship “on who they are, not who social media tells you they are.”

But it begins, at least four panelists said, with curriculum.

“Point-blank, period, full-stop: Decolonize your curriculum,” Hardy said. “Black males need to see themselves reflected in your curriculum in a tangible and authentic way. Tangible and authentic means don’t just troll out that Martin Luther King speech in February.”

Panelists suggested asking students what they want to read, what they want to study. Find out their interests so that you, as an educator, can find creative ways to incorporate those interests. You can do this even when you’re told what curriculum to use, Lewis said.

“It’s that careful interplay between recognizing what room does this curriculum provide for me to supplement or add,” Lewis said, “and then using those as opportunities to add in other materials, other readings, other resources.”

He spoke of his experience teaching high school literature, using books he loved. The second largest subgroup in his class were Hispanics. In conversations with them about what they liked to read, he realized a lot of gaps in his choices.

He let them take charge of choosing supplemental texts where they could see themselves in the readings. That engaged them and allowed them the opportunity to talk about their personal experiences and educate classmates from different backgrounds about their lives.

Safrit and Hardy echoed Lewis’s sentiments, saying you don’t have to be a teacher of color to teach books by authors of color:

For North Carolina’s Exceptional Children, Safrit and Hardy said, reaching them through core instruction is vital. There is a difficult line between overincluding students of color in special education — often because of behavioral issues or implicit bias — and underserving them through supports. Focusing on differentiated core instruction can catch kids who are falling through the cracks, or stuck trying to get in.

One attendee added in the chat: “Look at funding — often schools with fewer resources have high populations of Black males in special education. So … core curriculum is vital.”

3. Engaging each and every child

Wallace said he doesn’t focus on all students. Don’t call his superintendent yet, though. What he means is that he wants to do better than focusing on all.

“I’ve always said ‘each and every,’” Wallace said. “Because sometimes we can get lost in ‘all.’ We can always say ‘all of this’ and ‘all of that.’ It’s easy for kids to hide in all, and it’s easy for teachers to overlook every child in all.”

Engaging with students can lead to an understanding of their “situationality,” a term borne from Friere’s study of “Situationality” Model. Damion Lewis of Wake County Public Schools System and Shaftina Snipes of Charlotte-Mecklenburg School System reminded attendees that not every child comes to school with the same personal and social circumstances.

They introduced attendees to Jesus, who was born in the United States. His parents came to America when they were children and didn’t know they were illegal immigrants. When Jesus entered high school, his father died. A couple of years later, when he was 17, Jesus’s mother was deported. Jesus was left supporting his two younger siblings and attended school just enough to stay on schedule so as to remain under DACA protection.

“What’s our point here?” Lewis said. “Our current educational structure does not formally support or provide support for students like [Jesus] or students in similar situations. Unfortunately, equity is questionable.”

Equity means discovering these situations and finding solutions that ensure personal and social circumstances don’t prevent students from achieving their academic potential.

A session titled “Reclaiming Our Identities: A Latinx Perspective on Education in NC” underscored the importance of talking with students to learn their circumstances. Panelists Trilce Marquez and Dayson Pasion spent most of the session telling their stories. Attendees engaged in chat discussions throughout, connecting with the presenters and slowly feeling as if they began to know them.

That’s what Marquez and Pasion advocated: Listen to students. Hear their stories. Embrace their identities. One participant wrote in the chat: “We actually force kids to remove their identity when they enter into the school system. We rebrand them with a white brand that is acceptable for our white teachers.” Another responded: “We have to hear their stories. We have to listen to them.”

4. Include top influencers — the students

Porter talked about the difference between power and influence. Administrators, teachers, staff — all of these groups may have power inside the school. But students often have more influence over fellow students. That’s why he takes a collaborative approach with students on educational equity.

Here’s what he had to say about it:

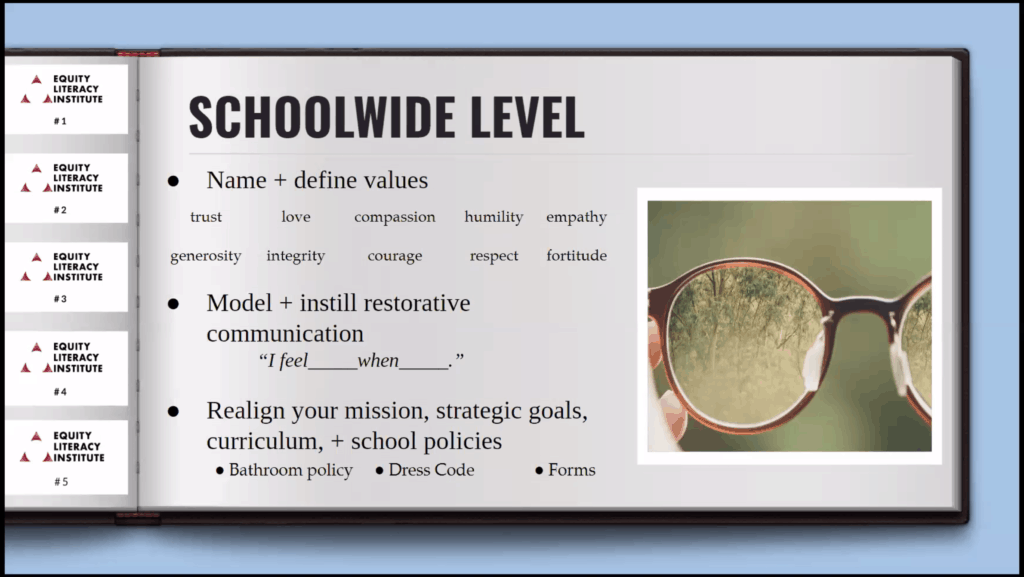

5. School design and culture

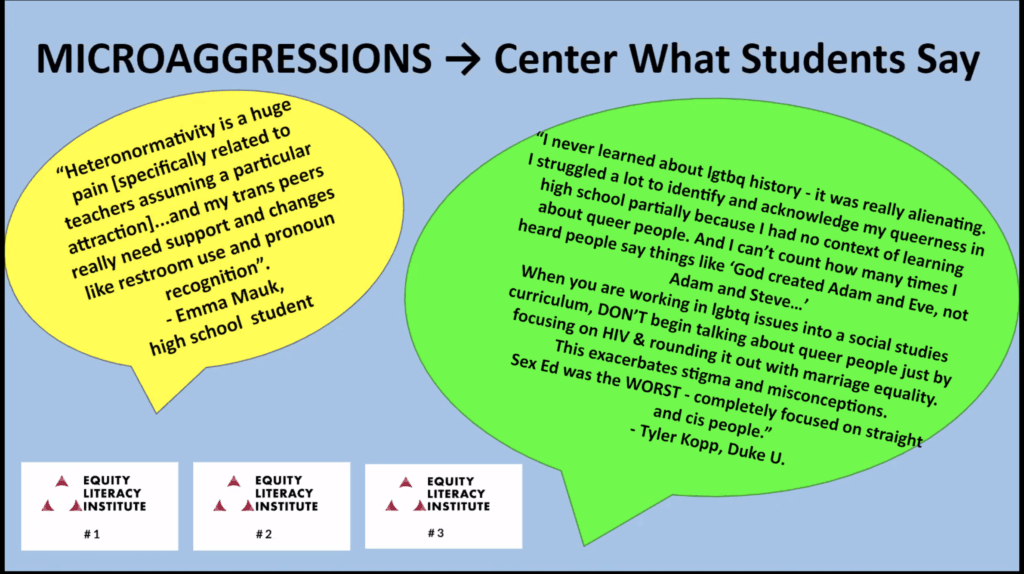

Think about the first community you were a part of — apart from your family. Kayce Smith and Dana Stachowiak of UNC Wilmington talked about creating communities and pedagogies of care for LGBTQ students, and focused on how educators can create a safe and healing environment.

They asked attendees to remember what it felt like to be a part of that community, what needs it served — and what needs it failed to meet.

Smith and Stachowiak said LGBTQ students are more likely to suffer from depression, suicidal ideation, and self-harm than peers who are straight or don’t know their orientation. Noting that students can’t learn if they don’t feel safe, they encouraged educators to move beyond prescriptive safety measures.

“Communities of care encourage us to take that one step further and recognize oppression and how oppression has played a part in trauma that students experience — that people experience,” Stachowiak said. “So if we think about safety and health and well-being of our students being priorities, it requires more than for us to just say, ‘Oh, we need them to be safe.’ … If we back out and see communities of care as a larger approach to not just recognizing trauma but recognizing the oppression that is a part of that trauma, that can be helpful.”

6. Representation at the front of classrooms

Several presenters spoke about the power of representation in the teacher population — how students can be affected by positively seeing teachers that look like they do.

While diversity, equity, and inclusion — as Pettigrew defined and described them — are important for every race and ethnicity of teachers in the schools, attracting and keeping diverse educators is especially powerful. But that means action and support from state and local governments, Snipes said.

“It’s very important that our students see themselves in their educators,” she said. “That doesn’t necessarily mean that a white teacher can’t teach an African-American student — that’s not what I’m saying. But what I’m saying is that when we are looking at truly educating our youth, it’s important that that dynamic shifts, and that everyone that’s in the building is properly represented.

“And the only way to do that is to, one, go back to making education a profession that people want to be a part of. And then, secondly, we all say that we do this for the passion — I know I say I do this because it’s my calling — but educators need to be paid properly because that will draw more people into the field.”

Watch full sessions from the conference at The Friday Institute’s YouTube channel here.

Recommended reading