Positioned strategically within Holly Springs’ booming biotechnology corridor, Pine Springs Preparatory Academy (PSPA) has experienced exponential enrollment growth since its launch in 2017. That year, the public charter school opened its doors to 509 students, said Bruce Friend, PSPA’s superintendent and chair of the state’s Charter Schools Review Board (CSRB).

During the current 2025-26 school year, however, PSPA is serving 5,568 students, a nearly 994% enrollment increase since the school’s inception. Final data from last year indicated PSPA enrolled 3,386 students — so 2,200 new students have enrolled this year alone.

How is such rapid growth possible at one school? PSPA offers families three distinct instructional formats: a traditional, in-person learning environment at two Holly Springs campuses; a blended model providing both virtual and in-person instruction; and a fully virtual statewide option leveraging a partnership with the online education provider K12. Each model is separate, but all three operate under the same charter.

“We’ve taken full advantage of current policies and statutes to allow us to serve as many families as possible,” said Gregg Sinders, PSPA’s board treasurer.

![]() Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

Sign up for the EdDaily to start each weekday with the top education news.

In fact, PSPA is the only North Carolina charter school to offer all three learning environments, according to the Office of Charter Schools (OCS).

“We’re a unicorn,” Friend said.

As an independent charter school, PSPA has expanded without the backing of an education or charter management organization, he added.

Even more growth is coming, and soon: PSPA is set to launch an upper school next fall at a third campus, now under construction in the Holly Springs Business Park.

Reasons for growth

Myriad factors have coalesced to fuel PSPA’s growth. PSPA’s culture and track record have built reputational capital in a populous area, school leaders said.

“We’re in one of the fastest-growing communities in North Carolina,” Sinders said, providing fertile ground for a high-quality school of choice to take root.

“One thing I hear from parents quite often — especially new families — is, ‘I don’t know what you’re doing at your school, but I have to be a part of it,’” said Lauren Johnson, PSPA’s elementary school principal. “That’s because of the community that we’ve built in Holly Springs and just the greater area as well.”

“A lot of our growth is directly tied to the results that we’ve had with our students,” Friend said. “Families talk about it, and they talk to their friends and other family members and want to be part of this. And I think our waitlists are one indication.”

All three models are at capacity this year. In addition, more than 1,200 students were on a waitlist earlier this fall for a seat in the traditional learning environment, Friend said.

The state’s changing policy landscape has also enabled expansion into new models. Recent legislation, enacted in 2023, authorized charter schools to seek CSRB approval for remote academies.

PSPA launched its remote academy last year. Both the blended and fully virtual options fall under the structure of the remote charter academy. This year, PSPA is one of eight charter schools operating a remote academy in North Carolina, according to OCS.

Such models have proven to be extremely popular at PSPA with families seeking flexible schooling environments.

“These are learning options that parents clearly want,” Friend said.

Enrollment, reach, and future expansion

PSPA’s 2025-26 student enrollment numbers are as follows:

- Traditional, in-person instruction (grades K-8): 1,275

- Blended academy (grades 4-10): 148

- Fully virtual model (grades K-12): 4,145

Initially, PSPA launched its traditional model with K-6 students at one campus, expanding to serve seventh and eighth grades. In 2021, PSPA opened a second Holly Springs campus for its middle schoolers. This year, those campuses are serving students from five counties.

When the upper school opens in 2026, it is expected to enroll 250 ninth graders. The goal, according to Friend, is to add one grade level per year, serving 1,000 students in grades 9-12 at capacity.

Located strategically in the business park, the upper school is expected to be a boon to area businesses.

“We will have a track — because of the biotech focus and presence in our community — where our students will be able to prepare for careers in the biotech industry, and we’ll do that through a partnership with Wake Tech Community College,” Sinders said. “Students will be able to graduate with a biotech certification and their high school diploma.”

“They want us as neighbors,” Friend said of the local biotechnology companies. “The companies that are operating in the business park here will tell you that they need workforce development … We are going to be able to help solve some of the challenges they have in terms of filling their workforce pipeline.”

Since the business park was not zoned for a school, PSPA pursued rezoning, seeking permission from the town. When school officials appeared before town leaders, private sector representatives came along as a gesture of support, Friend said.

The new upper school will also enable expansion of the blended academy, which will shift its in-person instructional component there. Over the next four years, PSPA expects to grow the blended academy to 400 students, Friend said.

This year, the blended academy draws students from six counties, with in-person instruction occurring at the elementary campus and at space rented from an Apex church.

The blended option, which grew out of a hybrid model the school began during the pandemic, is especially appealing to students who need scheduling flexibility. A lot of the school’s blended academy students are pursuing swimming, gymnastic, and equestrian pursuits, Friend said.

PSPA’s fully virtual model operates statewide. This year, it serves students in 113 of North Carolina’s 115 school districts, Friend said.

Last year, PSPA served 2,136 students through its remote charter academy (blended and fully virtual), according to a recent report to the General Assembly. Since then, the remote charter academy’s enrollment has doubled.

Among the state’s district and charter-run remote learning options, only NC Cyber Academy (with 2,442 students) and NC Virtual Academy (with 3,474 students) served more students than PSPA in 2024-25, report data showed. Historically, these two stand-alone schools have operated under the state’s virtual charter school pilot, which is set to conclude this year, so both are reapplying for approval as remote charter academies.

PSPA origins: location and quality

The catalyst for founding PSPA was simple but strategic, school leaders said: provide high quality options in an area that needed them.

“We got into this not because we felt Wake County Public Schools wasn’t doing a good job. It’s just (that) we knew the community had a need for additional seats,” Sinders said. “Our mission was to be a destination of choice for families and a destination of choice for teachers.”

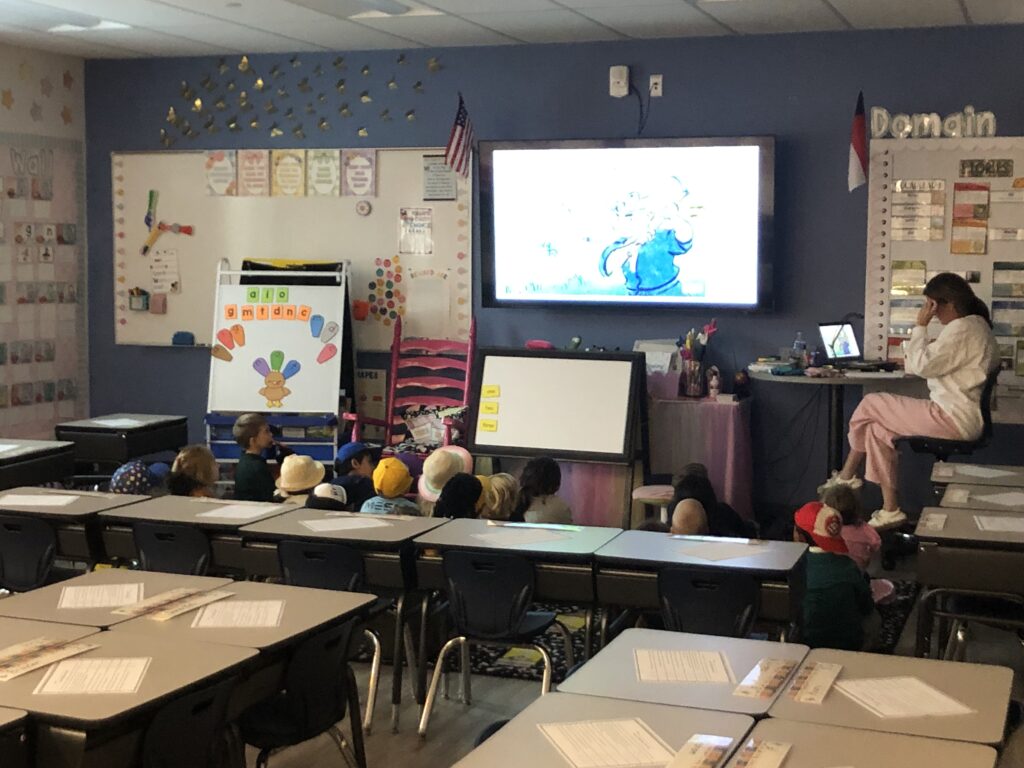

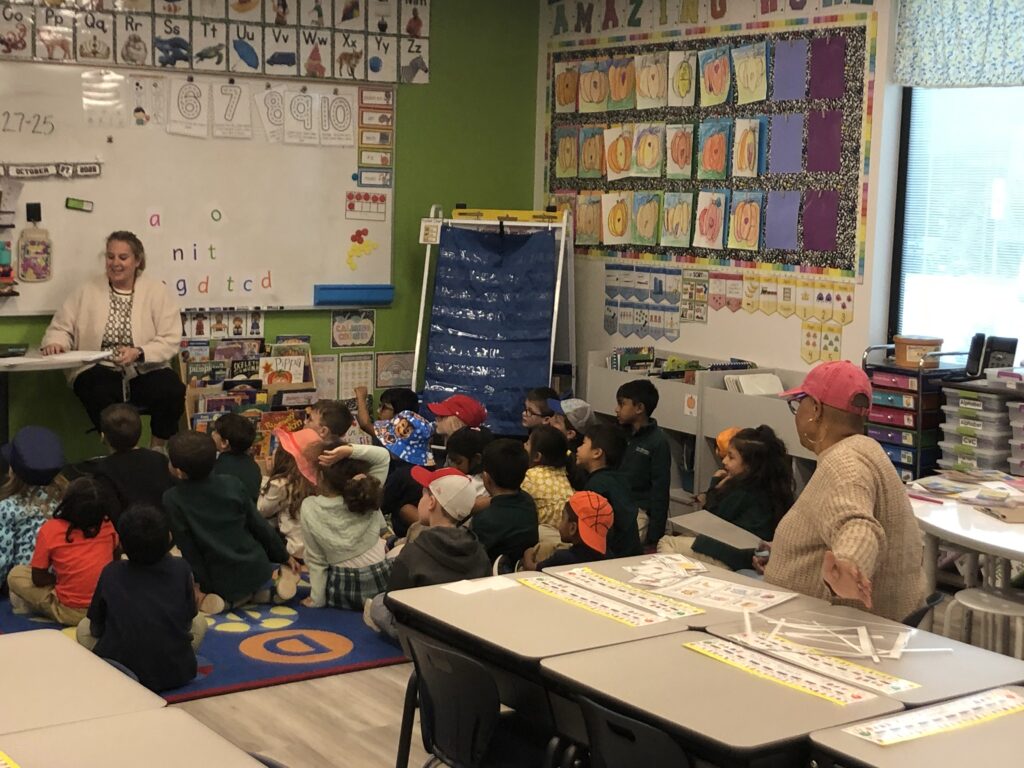

A key lever for school quality at PSPA is its integration of project-based learning (PBL) throughout the curriculum.

“We live in a world today where everything that we achieve comes from a group of people coming together trying to solve a problem. This is exactly what we do with project-based learning,” said Jodi Rubin, the school’s PBL coordinator and instructional coach.

Seventh graders are learning about probability in math, Rubin said. They create a compound probability-based game that elementary school students play. Eighth graders are working on problem-solving within the biotechnology field, leveraging curriculum from NIIMBL, a public-private biopharmaceutical partnership.

Along the way, students hone valuable skills. “We hear so much from high schools (about) how our kids do … the soft skills of working in a group, problem-solving, and then being able to present their knowledge,” said Johnson.

Families in the traditional model speak out

Nydia Lerma, a second grade teacher’s assistant at PSPA with two children at the school, said she and her husband were looking for a school that “mimicked” their education in Mexico. “My husband and I always went to private schools, and we were looking for a smaller community,” she said.

She found it at PSPA. In Mexico, “this the kind of education you get only if you pay,” she said. “I love that idea of having a school without tuition, and I also like the program that they were using for curriculum.”

Rubin’s two children also attend PSPA. Third grader Mackenzie Rubin said the hands-on focus has helped her retain important content.

“I learn better with crafts,” she said, describing a recent lesson on the human body that involved groups making and labeling a paper skeleton. “That helped me memorize where everything was.”

For Lainey Hagen, a seventh grader whose twin sister and brother also attend PSPA’s middle school campus, schoolwork has included “a lot of cooperation and hands-on experiments with different projects,” she said. “It really makes it different from a lot of schools.”

Hagen, whose mother works in the PSPA office, especially enjoyed the school’s “Pioneers with a Purpose” program, pairing older and younger students. “I loved teaching and reading to the little kids in the morning, and I loved helping with car line,” she said. “That was really fun.”

With remote learning, some growing pains

Friend’s experience with virtual learning prepared him for expansion through a remote charter academy. “I’ve been doing this for three decades,” he said. “I helped open one of the very first virtual schools in the country in 1996-97.”

The remote academy’s launch has not been without growing pains, however. “We certainly had a lot of challenges that first year,” Friend said.

Testing for the fully virtual model was daunting. “That was a massive undertaking that we had to go through last year” with students statewide, including provision of EC (Exceptional Children) services, he said. “With our partner, we had to set up testing locations all across the state and then get the families there as well.”

This year, new 2024-25 state accountability data reported separate school performance grades for charter schools and their remote academies. The separate grades are a requirement of state statute passed this year.

While PSPA’s brick and mortar school earned a 2024-25 performance grade of B, the remote charter academy earned a grade of F for its first year.

Economically disadvantaged students made up 72.2% of the population at PSPA’s remote charter academy last year, the highest of any remote charter academy or virtual charter in the state, the remote academy report showed.

A presentation to the State Board of Education (SBE) this fall referenced lower school performance grades at remote academies serving more students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, while also noting grade variation among these schools.

Schools serving higher percentages of economically disadvantaged students generally posted lower School Performance Grades (SPG). At the same time, some academies performed better than expected, while others fell well below predicted levels. Identifying and sharing effective practices from schools exceeding expectations may help inform improvement strategies for others.

State Board of Education presentation

Separating out school performance grades for traditional and remote charter learning models is important, Friend said. “The students who are in my remote academy are in many ways quite different from the students who come here every single day.”

Fully virtual students often reflect a more fluid student population compared to students in traditional models, he added. They may move to other learning environments throughout their education or even switch during the same academic year.

The remote academy pool can also be quite diverse. Students in the fully virtual model may lag behind in credits, Friend said. For some, that environment may represent a last chance to earn a high school diploma. Others in the fully virtual or blended environment, he said, may be “high fliers” who need more flexibility.

Friend’s experience in online learning has also shaped his expectations around the trajectory of academic improvement. While students may improve during that first year, it typically takes three years in a fully virtual environment to start seeing academic gains, he said.

As the remote academy moves through its second year, changes are ahead.

“We’re still growing,” Friend said. “We still have a lot of work to do.”

One change may involve separating the remote academy into its own school. New state statute allows remote charter academies with 250 or more students to request CSRB permission to operate as a stand-alone charter school. PSPA is moving in that direction, Friend said.

In the end, PSPA’s expansion and growth have prompted reflection on the school’s origins and founders’ enduring commitment to educational quality.

“We all shared a common belief, which is that we wanted to provide a high quality school for the families in a fast growing community. That was the North Star. It always was and still is,” Friend said. “But to go from where we all signed the application in my living room to what we have today is just beyond imagination.”

“We’ve got to make sure that we’re serving our students well,” he added. “(If) we don’t do that, all of this goes away.”

Editor’s note: Kristen Blair currently serves as the communications director for the North Carolina Coalition for Charter Schools. She has written for EdNC since 2015, and EdNC retains editorial control of the content.

Gregg Sinders, the board treasurer at Pine Springs quoted in the article, is also the Coalition’s treasurer. Dave Machado, the Coalition’s executive director (not mentioned in the article) serves on the Pine Springs board.

Recommended reading