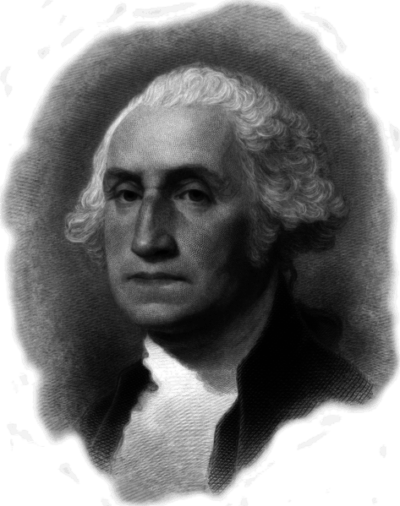

Promote then, as an object of primary importance, institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge. In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened. – George Washington, 1796

The nation’s first president did not deliver his “farewell address’’ with a speech. Rather, he had it published in a Philadelphia newspaper.

George Washington did not write it all himself. He had Alexander Hamilton and James Madison as ghostwriters, and John Jay as an editor. Those three had written the Federalist Papers.

The “farewell address,” writes journalist John Avlon, is “the most famous speech you’ve never read.” Avlon, editor in chief of The Daily Beast, a national news website, and a frequent CNN commentator, is the author of a new book, Washington’s Farewell: The Founding Father’s Warning to Future Generations.

The address1 opens with Washington’s announcement that he would not seek a third term as president, a crucial decision that established that the young nation would not have a lifetime sovereign but would have regular elections. Washington warned against the “expedients of party,’’ even as the 1796 presidential election produced the first political parties: the Federalists of John Adams vs. the Democratic-Republicans of Thomas Jefferson.

In today’s politics of powerful low-tax, anti-government forces, it is striking to read Washington’s admonition to Americans of his time. Washington described taxes as “inconvenient and unpleasant,’’ but he stated directly that “to have revenue there must be taxes.” In a nation as extensive as the United States, then with the original 13 states, Washington said, “government of as much vigor as is consistent with the perfect security of liberty is essential. Liberty itself will find in such a government, with powers properly distributed and adjusted, its surest guardian.”

While Washington’s address contains only a two-sentence paragraph on education, Avlon devotes a chapter to the context and backstory. Washington actually wanted to say more – to press for his idea of a “national university’’ – but Hamilton resisted, arguing for a general statement rather than a specific proposal. Throughout his term, Washington had promoted a “national university’’ as well as a military academy.

Congressional resistance to a national university, Avlon writes, “drove the focus for public education toward the creation of state universities, such as the University of North Carolina and Jefferson’s beloved University of Virginia.”

Just before Washington died in 1799, a small Virginia college was named for him, and he gave it a modest bequest. It is now Washington and Lee University. The U.S. Military Academy at West Point was founded in 1802 during the Jefferson presidency. A university, located in the Foggy Bottom section of the nation’s capital, was chartered during the presidency of James Monroe, and it was renamed The George Washington University in 1904.

During Washington’s presidency, the United States was a largely agrarian nation, with community schools scattered about and a few institutions of higher education such as Harvard and King’s College, now Columbia University, in New York. Avlon reports that Washington did not have a higher education at such institution as did Madison, Adams, and Jefferson.

“And so, as the young republic emerged unsteadily,” he writes, “the most unschooled founding father emerged as the leading proponent of national education as a means to develop an American character and our success as a self-governing people.” Washington, he writes, “saw public education as a hedge against would-be demagogues and regional divisions.”

In his will, Avlon reports, Washington freed his slaves and provided that their sons and daughters “be taught to read and write…” In addition, he gave money to Alexandria, Va., to set up a “free school’’ for the education of orphans and the children of indigent parents.

Recommended reading